Battle of Kars (1745)

| Battle of Kars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman–Persian War (1743–46) and the Campaigns of Nader Shah | |||||||

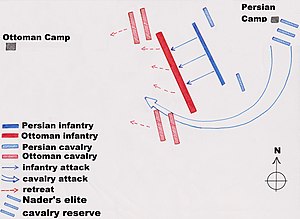

A diagram of the battle of Kars, illustrating the devastating flanking manoeuvre by Nader's cavalry reserve | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Persian Empire | Ottoman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Nader Shah | Mehmet Yegen Pasha † Abdollah Pasha Jebhechi | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 140,000[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~8,000[5] | 35,000[5]

| ||||||

The Battle of Kars (19 August 1745) was the last major engagement of the Ottoman-Persian War. The battle resulted in the complete and utter destruction of the Ottoman army. It was also the last of the great military triumphs of Nader Shah. The battle was in fact fought over a period of ten days in which the first day saw the Ottomans routed from the field, followed by a series of subsequent blockades and pursuits until the final destruction of the Ottoman army. The severity of the defeat, in conjunction with another defeat near Mosul, ended any hopes of Ottoman victory and forced them to enter into negotiations with a significantly weaker position than they would otherwise have occupied.[6]

Ottoman armies march east

[edit]During Nader's last punitive expedition in Dagestan, the Persian army moved south after devastating the region with many settlements razed to the ground and their inhabitants put to the sword. On June 14, 1745 Nader returned to Derbent remaining there for months before setting out south. He became extremely ill and had to be carried in a litter before the army halted at Yerevan.

The court physicians nursed the Shah back to health. Nader Shah was informed that two large Ottoman armies were headed eastward to his borders. One headed to Kars and the other to Mosul. Nader Shah immediately went on to the offensive and also split his forces into two. Nassrollah Mirza, Nader's son, was given a large component of the Persian army with the objective of defeating the Ottomans headed for Mosul and Nader himself set out for Kars where he unsuccessfully besieged the city in 1744.

Battle

[edit]Nader's army marched west past Yerevan when news was brought of the Ottoman army's departure from Kars under the command of Yegen Mohammad Pasha. Nader continued west and camped upon a hill near Yeghevārd. This was the same hill Nader had made camp on approximately 10 years previously when he had crushed an Ottoman army at the Battle of Yeghevārd. Yegen Pasha advanced until 10-12 kilometres from the Persian army and ordered his men to build extensive fortifications around their camp.

First day of battle

[edit]On 9 August the Ottomans began deploying 40,000 Janissary Infantry and 100,000 Sipahi Cavalry in the "European manner" with columns of infantry in the centre, artillery batteries interspersed between these columns and the cavalry in two bodies each on either flank.[7] Nader ordered his Jazāyerchi to advance against the centre and after firing a single massed volley, draw their shamshirs and charge. The battle raged with either side feeding in a steady stream of reinforcements into the centre.

The Ottoman cavalry held back due to their inferiority to their Persian counterparts.[8] Unlike in many other battles Nader fought in his career, he commanded the battle of Kars from his camp with messengers sending out his orders and returning with reports from the battlefield. By afternoon, Nader's retainers brought back reports from the battlefield which indicated there would be no decisive conclusion either way. Nader decided to don his armour and mount his horse.[5]

Nader led a force of 40,000 elite cavalry from the Savaran-e Sepah-e Khorasan (translated as the "Riders of the Army of Khorasan") he had held in reserve against the flank of the Ottoman army in a huge attack. The ferocity of the fighting was such that two horses were shot from under Nader, but the Ottoman army could not sustain the impact of the charge and broke up. A contingent of Anatolian troops from Asia minor (15,000 men in all) fled, leaving the rest of the Ottoman army to retreat in utter chaos and confusion. The Persian army engaged in a pursuit until dusk and subsequently returned to their camp.

Encirclement of the Ottomans

[edit]On the next day Nader sent forth a fowj (a unit approximately the equivalent of a regiment) to cut the logistical line of the Ottoman army back to Kars. The Persian army began surrounding the Ottoman camp. A few skirmishes ensued but all attempts by the Ottomans to break the encirclement failed. Yegen Pasha attempted to remedy this by deploying his guns. The Persian artillery batteries were deployed and a counter-battery fire was commenced in which the Ottoman artillery was outclassed in both accuracy and rate of fire. Many of Yegen Pasha's artillery pieces were destroyed, their components scattered across the field. This demoralising event brought the Ottomans trapped inside the camp's walls to the brink of mutiny. A stream of deserters came to the Persian camp bringing news of the ongoing turmoil in the Ottoman battlements. In the dark of night the Ottoman army silently abandoned their fortifications and marched west, but the Persian army immediately set out, hot on their heels, caught up and encircled them once more.[5]

On 19 August a letter was brought to Nader bearing news of the outcome of the battle of Mosul. Nassrollah Mirza had crushed the Ottoman army sent to the Mosul Eyalet and was requesting the Shah's permission to advance deeper into Ottoman Mesopotamia. Nader Shah ordered this letter to be taken to Yegen Pasha in a bid to convince him of the futility of further resistance. However, as the Persian emissaries entered the encampment they found the Ottoman troops had risen in mutiny. It is unclear as to whether they rose in mutiny after hearing of Yegen Pashah's suicide or in fact, had killed Yegen Pasha in an act of mutiny. Fowj after fowj of the Ottomans broke away from the camp and fled desperately. The Ottoman soldiers screamed "oh people of Mohammad, flee, flee!" as they were ruthlessly pursued and cut down by the Persian cavalry.[5]

Casualties

[edit]The terrible fate of the Ottoman army ended all hope of a military victory for Istanbul. The large numbers of killed and wounded on both sides indicated the harshness of the struggle as well as the courage and quality of the Ottoman soldiers. The 8,000 casualties suffered by the Persian army in the first day of battle was a testament to the severity of the fighting, although the Persians suffered hardly any casualties after that whilst the Ottoman casualties continued to mount exponentially.

Estimates range from 28,000 all the way to 50,000 men in total. The most plausible gives 12,000 killed, 18,000 wounded and 5,000 captured bringing the sum of men hors de combat to 35,000. Nader allowed all the wounded soldiers which had been captured return to Kars so that they may find succour for their wounds.

Battle near Mosul

[edit]A separate action was fought around the same time near Mosul. After receiving news of the approach of two Ottoman armies from the west towards his borders, the Shah of Persia, Nader Shah, had divided his forces in two. A contingent was put under the command of Nader's son, Nasrollah Mirza, as he was named after his victory at Karnal. Nasrollah Mirza set out south west in order to find and destroy the Ottoman army.[9]

The Ottoman commander, Abdullah Pasha, marched into Mosul Eyalet where he was joined by the local Ottoman forces as well as a significant body of Kurdish auxiliaries. However, when the Persian army gave battle it inflicted a crushing defeat.[10][11] The severity of the Ottoman defeat was such that Nassrollah Mirza wrote to his father, Nader, requesting permission to escalate the situation into a full-scale invasion of Ottoman Iraq. The letter reached Nader Shah on the last day of the Battle of Kars where Nader had also gained an overwhelming victory against Yegen Pasha.[12][13]

Aftermath

[edit]The overall outcome of both victories forced the Ottomans to concede to negotiating under unfavourable circumstances. Having both its armies destroyed, Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) lost all possibility for gaining any military leverage against Iran. However, Nader Shah chose not to launch a counter invasion of the Ottoman Empire, despite annihilating any Ottoman offensive capabilities, putting them completely on the defensive. Instead he pursued a diplomatic solution for the cessation of hostilities. Soon after an exchange of diplomats, the treaty of Kerden was signed which officially ended the war in 1746.

As the Ottoman and Safavid Empires declined, their conflicts helped shape the political borders of modern Iran and Turkey by the 17th century, influencing the current sectarian makeup of Islam. Shias now form the majority in Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrain, and a significant portion in Lebanon, while Sunnis dominate in over 40 countries from Morocco to Indonesia.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tucker 2011, p. 743.

- ^ Ghafouri, Ali(2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now, p. 401. Etela'at Publishing

- ^ Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein (2008). The Great Batlles of Nader Shah, p. 126. Donyaye Ketab

- ^ Lockhart, Laurence. Nadir Shah: A critical study based mainly upon contemporary sources, p. 312. Luzac & Company

- ^ a b c d e f Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, p. 339. I.B. Tauris

- ^ Lockhart, Laurence. Nadir Shah: A critical study based mainly upon contemporary sources, p. 315. Luzac & Company

- ^ Alam Aray-e Naderi, Mohammad Kazim Keshmiri, 3 volumes, Tehran university press

- ^ The Army of Nader Shah, Michael Axworthy, Iranian Studies, volume 40, number 5, December 2007, (Taylor & Francis), 642.[1] Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mohammad Kazem Marvi Yazdi, Alam Ara-ye Naderi (Rare views of the world), 3 vols., Ed. Amin Riyahi, Tehran, Third Edition, 1374/1995

- ^ Mahdī Khān Astarābādī (1807) [1770]. "Histoire De Nader Chah". Works of Sir William Jones (in French). Vol. 12. Translated by William Jones. London: J. Stockdale. pp. 102–103. OCLC 11585120. Jahangushaye Naderi.

- ^ Herbert John Maynard (1885). Nadir Shah. H. B. Blackwell. p. 49. OCLC 493917070.

- ^ Laurence Lockhart (1938). Nadir Shah: A Critical Study Based Mainly Upon Contemporary Sources. London: Luzac. pp. 250, 340. OCLC 580906461.

- ^ Michael Axworthy (2010). Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris. pp. 289–291. ISBN 9780857733474.

- ^ Robert McMahon, "The Sunni-Shia Divide," The Council on Foreign Relations, April 27, 2023, Accessed September 18, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2011). "1743–1747: Southwest Asia: War between the Ottoman Empire and Persia". A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Vol. II. ABC-CLIO.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch