Krak des Chevaliers

| Krak des Chevaliers | |

|---|---|

قلعة الحصن | |

| by Al-Husn, Talkalakh District, Syria | |

Krak des Chevaliers from the southwest | |

| Coordinates | 34°45′25″N 36°17′41″E / 34.7570°N 36.2947°E |

| Type | Concentric castle |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by |

|

| Open to the public | Accessible |

| Condition | Mostly good but damaged due to Syrian Civil War |

| Site history | |

| Built |

|

| Built by |

|

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | |

| Part of | Crac des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 1229-001 |

| Inscription | 2006 (30th Session) |

| Endangered | 2013–present |

| Area | 2.38 ha |

| Buffer zone | 37.69 ha |

Krak des Chevaliers (French: [kʁak de ʃ(ə)valje]; Arabic: قلعة الحصن, romanized: Qalʿat al-Ḥiṣn, Arabic: [ˈqalʕat alˈħisˤn]; Old French: Crac des Chevaliers or Crac de l'Ospital, lit. 'karak [fortress] of the hospital'; from Classical Syriac: ܟܪܟܐ, romanized: karəḵā, lit. 'walled city') is a medieval castle in Syria and one of the most important preserved medieval castles in the world. The site was first inhabited in the 11th century by Kurdish troops garrisoned there by the Mirdasids. In 1142 it was given by Raymond II, Count of Tripoli, to the order of the Knights Hospitaller. It remained occupied by them until it was reconquered by the Muslims in 1271.

The Hospitallers began rebuilding the castle in the 1140s and were finished by 1170 when an earthquake damaged the castle. The order controlled castles along the border of the County of Tripoli, a state founded after the First Crusade. Krak des Chevaliers was among the most important and acted as a center of administration as well as a military base. After a second phase of building was undertaken in the 13th century, Krak des Chevaliers became a concentric castle. This phase created the outer wall and gave the castle its current appearance. The first half of the century has been described as Krak des Chevaliers' "golden age". At its peak, Krak des Chevaliers housed a garrison of around 2,000. Such a large garrison allowed the Hospitallers to exact tribute from a wide area. From the 1250s the fortunes of the Knights Hospitaller took a turn for the worse and in 1271 the Mamluk Sultanate captured Krak des Chevaliers after a siege lasting 36 days, supposedly by way of a forged letter purportedly from the Hospitallers' Grand Master that caused the knights to surrender.

Renewed interest in Crusader castles in the 19th century led to the investigation of Krak des Chevaliers, and architectural plans were drawn up. In the late 19th or early 20th century a settlement had been created within the castle, causing damage to its fabric. The 500 inhabitants were moved in 1933 and the castle was given over to the French Alawite State, which carried out a program of clearing and restoration. When Syria declared independence in 1946, it assumed control.

Today, the village of al-Husn exists around the castle and has a population of nearly 9,000. Krak des Chevaliers is approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) west of the city of Homs, close to the border of Lebanon, and is administratively part of the Homs Governorate. Since 2006, the castles of Krak des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din have been recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.[1] It was partially damaged in the Syrian civil war from shelling and recaptured by the Syrian government forces in 2014. Since then, reconstruction and conservation work on the site had begun. Reports by UNESCO and the Syrian government on the state of the site are produced yearly.[2]

Etymology

[edit]"Krak" is derived from karak, the Syriac word for a walled city or fortress.[3] Before the arrival of the crusaders, the local Arab ruler had established a fortification on the site manned by Kurds, giving it the name, in Arabic, of Ḥoṣn al-Akrād (حصن الأكراد), or "fort of the Kurds".[4] Following the construction of the present castle, the crusaders (whose elite spoke either Old French or, in Tripoli, possibly Old Occitan[5]) corrupted that name into Le Crat and then, as a result of confusing it with karak, the name evolved into Le Crac.[6]

Because of its association with the Knights Hospitallers, it was known as Crac de l'Ospital (Fortress of the Hospital) during the Middle Ages.[7] The name was later romanticised[8] to become Krak des Chevaliers in French in the 19th century,[9] meaning "Fortress of the Knights".[4]

Location

[edit]

The castle sits atop a 650-metre-high (2,130 ft) hill east of Tartus, Syria, in the Homs Gap.[10] On the other side of the gap, 27 kilometres (17 mi) away, was the 12th-century castle of Gibelacar (Hisn Ibn Akkar).[11] The route through the strategically important Homs Gap connects the cities of Tripoli and Homs. To the north of the castle lies the Syrian Coastal Mountain Range, and to the south, Lebanon. The surrounding area is fertile,[12] benefiting from streams and abundant rainfall.[13] Compared to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the other Crusader states had less land suitable for farming; however, the limestone peaks of Tripoli were well-suited to defensive sites.[14]

Property in the County of Tripoli, granted to the Knights in the 1140s, included the Krak des Chevaliers, the towns of Rafanea and Montferrand, and the Beqa'a plain separating Homs and Tripoli. Homs was never under Crusader control, so the region around the Krak des Chevaliers was vulnerable to expeditions from the city. While its proximity caused the Knights problems with regard to defending their territory, it also meant Homs was close enough for them to raid. Because of the castle's command of the plain, it became the Knights' most important base in the area.[13]

History

[edit]

Origins and Crusader period

[edit]According to the 13th-century Arab historian Ibn Shaddad, in 1031, the Mirdasid emir of Aleppo and Homs, Shibl ad-Dawla Nasr, established a settlement of Kurdish tribesmen at the site of the castle,[15] which was then known as "Ḥiṣn al-Safḥ".[16] Nasr restored Hisn al-Safh to help reestablish the Mirdasids' access to the coast of Tripoli after they lost nearby Hisn Ibn Akkar to the Fatimids in 1029.[16] Due to Nasr's garrisoning of Kurdish troops at the site, the castle became known as "Ḥiṣn al-Akrād" (Fortress of the Kurds).[15][16] The castle was strategically located at the southern edge of the Jibal al-Alawiyin mountain range and dominated the road between Homs and Tripoli.[15] When building castles, engineers often chose elevated sites, such as hills and mountains, that provided natural obstacles.[17]

In January 1099, on the journey to Jerusalem during the First Crusade, the company of Raymond IV of Toulouse came under attack from the garrison of Hisn al-Akrad, the forerunner of the Krak, who harried Raymond's foragers.[18] The following day, Raymond marched on the castle and found it deserted. The crusaders briefly occupied the castle in February of the same year but abandoned it when they continued their march towards Jerusalem. Permanent occupation began in 1110 when Tancred, Prince of Galilee took control of the site.[19] The early castle was substantially different from the extant remains, and no trace of this first castle survives at the site.[20]

The origins of the order of the Knights Hospitaller are unclear, but it probably emerged around the 1070s in Jerusalem. It started as a religious order that cared for the sick, and later looked after pilgrims to the Holy Land. After the success of the First Crusade in capturing Jerusalem in 1099, many Crusaders donated their new property in the Levant to the Hospital of St John. Early donations were in the newly formed Kingdom of Jerusalem, but over time the order extended its holdings to the Crusader states of the County of Tripoli and the Principality of Antioch. Evidence suggests that in the 1130s, the order became militarised[21] when Fulk, King of Jerusalem, granted the newly built castle at Beth Gibelin to the order in 1136.[22] A papal bull from between 1139 and 1143 may indicate the order hiring people to defend pilgrims. There were also other military orders, such as the Knights Templar, that offered protection to pilgrims.[21]

Between 1142 and 1144 Raymond II, Count of Tripoli, granted property in the county to the order.[23] According to historian Jonathan Riley-Smith, the Hospitallers effectively established a "palatinate" within Tripoli.[24] The property included castles with which the Hospitallers were expected to defend Tripoli. Along with Krak des Chevaliers, the Hospitallers were given four other castles along the borders of the state, which allowed the order to dominate the area. The order's agreement with Raymond II stated that if he did not accompany knights of the order on campaign, the spoils belonged entirely to the order, and if he was present it was split equally between the count and the order. Further, Raymond II could not make peace with the Muslims without the permission of the Hospitallers.[23] The Hospitallers made Krak des Chevaliers a center of administration for their new property, undertaking work at the castle that would make it one of the most elaborate Crusader fortifications in the Levant.[25]

After acquiring the site in 1142, they began building a new castle to replace the former Kurdish fortification. This work lasted until 1170, when an earthquake damaged the castle. An Arab source mentions that the quake destroyed the castle's chapel, which was replaced by the present chapel.[26] In 1163, the Crusaders emerged victorious over Nur ad-Din in the Battle of al-Buqaia near Krak des Chevaliers.[27]

Drought conditions between 1175 and 1180 prompted the Crusaders to sign a two-year truce with the Muslims, but without Tripoli included in the terms. During the 1180s, raids by Christians and Muslims into each other's territory became more frequent.[28] In 1180, Saladin ventured into the County of Tripoli, ravaging the area. Unwilling to meet him in open battle, the Crusaders retreated to the relative safety of their fortifications. Without capturing the castles, Saladin could not secure control of the area, and once he retreated the Hospitallers were able to revitalise their damaged lands.[29] The Battle of Hattin in 1187 was a disastrous defeat for the Crusaders: Guy of Lusignan, King of Jerusalem, was captured, as was the True Cross, a relic discovered during the First Crusade. Afterwards, Saladin ordered the execution of the captured Templar and Hospitaller knights, such was the importance of the two orders in defending the Crusader states.[30] After the battle, the Hospitaller castles of Belmont, Belvoir, and Bethgibelin fell to Muslim armies. Following these losses, the Order focused its attention on its castles in Tripoli.[31] In May 1188, Saladin led an army to attack Krak des Chevaliers, but on seeing the castle, decided it was too well defended and instead marched on the Hospitaller castle of Margat, which he also failed to capture.[32]

Another earthquake struck in 1202, and it may have been after this event that the castle was remodelled. The 13th-century work was the last period of building at Krak des Chevaliers and gave it its current appearance. An enclosing stone circuit was built between 1142 and 1170; the earlier structure became the castle's inner court or ward. If there was a circuit of walls surrounding the inner court that pre-dated the current outer walls, no trace of it has been discovered.[33]

The first half of the 13th century has been characterised as Krak des Chevaliers' "golden age". While other Crusader strongholds came under threat, Krak des Chevaliers and its garrison of 2,000 soldiers dominated the surrounding area. It was effectively the center of a principality which remained in Crusader hands until 1271, and was the only major inland area to remain constantly under Crusader control during this period. Crusaders who passed through the area would often stop at the castle, and probably made donations. King Andrew II of Hungary visited in 1218 and proclaimed the castle the "key of the Christian lands". He was so impressed with the castle that he gave a yearly income of 60 marks to the Master and 40 to the brothers. Geoffroy de Joinville, uncle of the noted chronicler of the Crusades Jean de Joinville, died at Krak des Chevaliers in 1203 or 1204 and was buried in the castle's chapel.[34]

The main contemporary accounts relating to Krak des Chevaliers are of Muslim origin and tend to emphasise Muslim success while overlooking setbacks against the Crusaders, although they suggest that the Knights Hospitaller forced the settlements of Hama and Homs to pay tribute to the Order. This situation lasted as long as Saladin's successors warred between themselves. The proximity of Krak des Chevaliers to Muslim territories allowed it to take on an offensive role, acting as a base from which neighboring areas could be attacked. By 1203, the garrison was making raids on Montferrand (which was under Muslim control) and Hama, and in 1207 and 1208 the castle's soldiers took part in an attack on Homs. Krak des Chevaliers acted as a base for expeditions to Hama in 1230 and 1233 after the amir refused to pay tribute. The former was unsuccessful, but the 1233 expedition was a show of force that demonstrated the importance of Krak des Chevaliers.[32]

In the 1250s, the fortunes of the Hospitallers at Krak des Chevaliers took a turn for the worse. A Muslim army estimated to number 10,000 men ravaged the countryside around the castle in 1252, after which the Order's finances declined sharply. In 1268, Master Hugues Revel complained that the area, previously home to around 10,000 people, now stood deserted and that the Order's property in the Kingdom of Jerusalem produced little income. He also noted that by this point there were only 300 of the Order's brethren left in the east. On the Muslim side, in 1260 Baibars became Sultan of Egypt, following his overthrow of the incumbent ruler Qutuz, and went on to unite Egypt and Syria. As a result, Muslim settlements that had previously paid tribute to the Hospitallers at Krak des Chevaliers no longer felt intimidated into doing so.[35]

As for Hugues Revel, some of the castellans of this castle are identified: Pierre de Mirmande (Grand Commander) and Geoffroy le Rat (Grand Master).[citation needed]

Baibars ventured into the area around Krak des Chevaliers in 1270 and allowed his men to graze their animals on the fields around the castle. When he received news that year of the Eighth Crusade led by King Louis IX of France, Baibars left for Cairo to avoid a confrontation. After Louis died in 1271, Baibars returned to deal with Krak des Chevaliers. Before he marched on the castle, the Sultan captured the smaller castles in the area, including Chastel Blanc. On 3 March, Baibars' army arrived at Krak des Chevaliers.[36] By the time the Sultan appeared on the scene, the castle may already have been blockaded by Mamluk forces for several days.[37] Of the three Arabic accounts of the siege, only one was contemporary, that of Ibn Shaddad, who was not present at the siege. Peasants who lived in the area had fled to the castle for safety and were kept in the outer ward. As soon as Baibars arrived, he erected mangonels, powerful siege weapons which he would later turn on the castle. In a probable reference to a walled suburb outside the castle's entrance, Ibn Shaddad records that two days later the first line of defences fell to the besiegers.[38]

Rain interrupted the siege, but on 21 March, immediately south of Krak des Chevaliers, Baibar's forces captured a triangular outwork possibly defended by a timber palisade. On 29 March, the attackers undermined a tower in the southwest corner, causing it to collapse whereupon Baibars' army attacked through the breach. In the outer ward, they encountered the peasants who had sought refuge in the castle. Though the outer ward had fallen, with a handful of the garrison killed in the process, the Crusaders retreated to the more formidable inner ward. After a lull of ten days, the besiegers conveyed a letter to the garrison, supposedly from the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller in Tripoli, which granted permission, (aman), for them to surrender on 8 April 1271.[39] Although the letter was a forgery, the garrison capitulated and the Sultan spared their lives.[38] The new owners of the castle undertook repairs, focused mainly on the outer ward.[40] The Hospitaller chapel was converted to a mosque and two mihrabs (prayer niches) were added to the interior.[41]

Later history

[edit]

During the Ottoman period (1516–1918), the castle housed a company of local janissaries and was the centre of the nahiye (tax district) of Hisn al-Akrad, attached first to the Tripoli Sanjak and later Homs, both part of the Tripoli Eyalet. The castle itself was commanded by a dizdar (castle warden). Several Turkmen and Kurdish tribes were settled in the area, and in the 18th century the district was mainly controlled by local notables from the Dandashi family. In 1894, the Ottoman government considered stationing a company of auxiliary soldiers there, but revised its plans after deciding the castle was too old and access too difficult. As a result, the capital of the district was then moved to nearby Talkalakh.[42]

After the Franks were driven from the Holy Land in 1291, European familiarity with the castles of the Crusades declined. It was not until the 19th century that interest in these buildings was renewed, so there are no detailed plans from before 1837. Emmanuel Guillaume-Rey was the first European researcher to scientifically study Crusader castles in the Holy Land.[43] In 1871, he published the work Etudes sur les monuments de l'architecture militaire des Croisés en Syrie et dans l'ile de Chypre; which included plans and drawings of the major Crusader castles in Syria, including Krak des Chevaliers. In some instances his drawings were inaccurate, however for Krak des Chavaliers they record features which have since been lost.[44]

Paul Deschamps visited the castle in February 1927. Since Rey had visited in the 19th century, a village of 500 people had been established within the castle. Renewed inhabitation had damaged the site: underground vaults had been used as rubbish tips and in some places the battlements had been destroyed. Deschamps and fellow architect François Anus attempted to clear some of the detritus; General Maurice Gamelin assigned 60 Alawite soldiers to help. Deschamps left in March 1927, and work resumed when he returned two years later. The culmination of Deschamp's work at the castle was the publication of Les Châteaux des Croisés en Terre Sainte I: le Crac des Chevaliers in 1934, with detailed plans by Anus.[45] The survey has been widely praised, described as "brilliant and exhaustive" by military historian D. J. Cathcart King in 1949[12] and "perhaps the finest account of the archaeology and history of a single medieval castle ever written" by historian Hugh Kennedy in 1994.[46]

As early as 1929, there were suggestions that the castle should be taken under French control. On 16 November 1933, Krak des Chevaliers was given into the control of the French state, and cared for by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The villagers were moved and paid F1 million between them in compensation. Over the following two years, a programme of cleaning and restoration was carried out by a force of 120 workers. Once finished, Krak des Chevaliers was one of the key tourist attractions in the French Levant.[47] Pierre Coupel, who had undertaken similar work at the Tower of the Lions and the two castles at Sidon, supervised the work.[48] Despite the restoration, no archaeological excavations were carried out. The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, which had been established in 1920, ended in 1946 with the declaration of Syrian independence.[49] The castle was made a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, along with Qal'at Salah El-Din, in 2006,[1] and is owned by the Syrian government.

Several of the castle's former residents built their houses outside the fortress and a village called al-Husn has since developed.[50] Many of the al-Husn's roughly 9,000 Muslims residents benefit economically from the tourism generated by the site.[50][51][52]

The Syrian Civil War began in 2011, prompting UNESCO to raise concerns that the war might damage cultural sites including Krak des Chevaliers.[53] The castle was shelled in August 2012 by the Syrian Arab Army, damaging the Crusader chapel.[54] It was damaged again in July 2013 by an airstrike conducted by the Syrian Arab Air Force during the Siege of Homs,[55] and once more on 18 August 2013.[citation needed] The Syrian Arab Army captured the castle and village after the Battle of Hosn in March 2014. Since then, UNESCO has published periodic reports about the state of the site, reconstruction and conservation measures.[56]

Architecture

[edit]

Writing in the early 20th century, T. E. Lawrence, popularly known as Lawrence of Arabia, remarked that Krak des Chevaliers was "perhaps the best preserved and most wholly admirable castle in the world, [a castle which] forms a fitting commentary on any account of the Crusading buildings of Syria".[57] Castles in Europe provided lordly accommodation for their owners and were centers of administration; in the Levant the need for defence was paramount and was reflected in castle design. Kennedy suggests that "The castle scientifically designed as a fighting machine surely reached its apogee in great buildings like Margat and Crac des Chevaliers."[58]

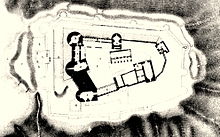

Krak des Chevaliers can be classified both as a spur castle, due to its site, and after the 13th-century expansion a fully developed concentric castle. It was similar in size and layout to Vadum Jacob, a Crusader castle built in the late 1170s.[59] Margat has also been cited as Krak des Chevaliers' sister castle.[60] The main building material at Krak des Chevaliers was limestone; the ashlar facing is so fine that the mortar is barely noticeable.[61] Outside the castle's entrance was a "walled suburb" known as a burgus, no trace of which remains. To the south of the outer ward was a triangular outwork and the Crusaders may have intended to build stone walls and towers around it. It is unknown how it was defended at the time of the 1271 siege, though it has been suggested it was surrounded by a timber palisade.[62] South of the castle, the spur on which it stands is connected to the next hill, so that siege engines can approach on level ground. The inner defences are strongest at this point, with a cluster of towers connected by a thick wall.[citation needed]

Inner ward

[edit]Between 1142 and 1170, the Knights Hospitaller undertook a building programme on the site. The castle was defended by a stone curtain wall studded with square towers which projected slightly. The main entrance was between two towers on the eastern side, and there was a postern gate in the northwest tower. At the center was a courtyard surrounded by vaulted chambers. The lay of the land dictated the castle's irregular shape. A site with natural defences was a typical location for Crusader castles and steep slopes provided Krak des Chevaliers with defences on all sides bar one, where the castle's defences were concentrated. This phase of building was incorporated into the later castle's construction.[26]

When Krak des Chevaliers was remodelled in the 13th century, new walls surrounding the inner court were built. They followed the earlier walls, with a narrow gap between them in the west and south, which was turned into a gallery from which defenders could unleash missiles. In this area, the walls were supported by a steeply sloping glacis which provided additional protection against both siege weapons and earthquakes. Four large, round towers project vertically from the glacis; they were used as accommodation for the Knights of the garrison, about 60 at its peak. The southwest tower was designed to house the rooms of the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller. Though the defences which once crested the walls of the inner wards no longer survive in most places, it seems that they did not extend for the entire circuit. Machicolations were absent from the southern face. The area between the inner court and the outer walls was narrow and not used for accommodation. In the east, where the defences were weakest, there was an open cistern filled by an aqueduct. It acted both as a moat and water supply for the castle.[63]

At the north end of the small courtyard is a chapel and at the southern end is an esplanade. The esplanade is raised above the rest of the courtyard; the vaulted area beneath it would have provided storage and could have acted as stabling and shelter from missiles. Lining the west of the courtyard is the hall of the Knights. Though probably first built in the 12th century, the interior dates from the 13th-century remodelling. The tracery and delicate decoration is a sophisticated example of Gothic architecture, probably dating from the 1230s.[64]

Chapel

[edit]

The current chapel was probably built to replace the one destroyed by an earthquake in 1170.[26] Only the east end of the original chapel, which housed the apse, and a small part of the south wall survive from the original chapel.[41] The later chapel had a barrel vault and an uncomplicated apse; its design would have been considered outmoded by contemporary standards in France, but bears similarities to that built around 1186 at Margat.[26] It was divided into three roughly equal bays. A cornice runs round the chapel at the point where the vault ends and the wall begins. Oriented roughly east to west, it was 21.5 metres (71 ft) long and 8.5 metres (28 ft) wide with the main entrance from the west and a second smaller one in the north wall. When the castle was remodelled in the early 13th century, the entrance was moved to the south wall. The chapel was lit by windows above the cornice, one at the west end, one on either side of the east bay, and one on the south side of the central bay, and the apse at the east end had a large window. In 1935, a second chapel was discovered outside the castle's main entrance, however it no longer survives.[65]

Outer ward

[edit]

Translation:

You may have bounty, you may have wisdom, you may be granted beauty; pride alone defiles all [these things] if it accompanies [them].

The second phase of building work undertaken by the Hospitallers began in the early 13th century and lasted decades. The outer walls were built in the last major construction on the site, lending the Krak des Chevaliers its current appearance. Standing 9 metres (30 ft) high, the outer circuit had towers that projected strongly from the wall. While the towers of the inner court had a square plan and did not project far beyond the wall, the towers of the 13th-century outer walls were rounded. This design was new and even contemporary Templar castles did not have rounded towers.[33] The technique was developed at Château Gaillard in France by Richard the Lionheart between 1196 and 1198.[66] The extension to the southeast is of lesser quality than the rest of the circuit and was built at an unknown date. Probably around the 1250s, a postern was added to the north wall.[67]

Arrow slits in the walls and towers were distributed to minimise the amount of dead ground around the castle. Machicolations crowned the walls, offering defenders a way to hurl projectiles towards enemies at the foot of the wall. They were so cramped, archers would have had to crouch inside them. The box machicolations were unusual: those at Krak des Chevaliers were more complex that those at Saône or Margat, and there were no comparable features amongst Crusader castles. However, they bore similarities to Muslim work, such as the contemporary defences at the Citadel of Aleppo. It is unclear which side imitated the other, as the date they were added to Krak des Chevaliers is unknown, but it does provide evidence for the diffusion of military ideas between the Muslim and Christian armies. These defences were accessed by a wall-walk known as a chemin de ronde. In the opinion of historian Hugh Kennedy, the defences of the outer wall were "the most elaborate and developed anywhere in the Latin east ... the whole structure is a brilliantly designed and superbly built fighting machine".[68]

When the outer walls were built in the 13th century the main entrance was enhanced. A vaulted corridor led uphill from the outer gate in the northeast.[69] The corridor made a hairpin turn halfway along its length, making it an example of a bent entrance. Bent entrances were a Byzantine innovation, but that at Krak des Chevaliers was a particularly complex example.[70] It extended for 137 metres (450 ft), and along its length were murder-holes which allowed defenders to shower attackers with missiles.[69] Anyone going straight ahead rather than following the hairpin turn would emerge in the area between the castle's two circuits of walls. To access the inner ward, the passage had to be followed round.[70]

Frescoes

[edit]

Despite its predominantly military character, the castle is one of the few sites where Crusader art (in the form of frescoes) has been preserved. In 1935, 1955, and 1978, medieval frescoes were discovered within Krak des Chevaliers after later plaster and white-wash had decayed. The frescos were painted on the interior and exterior of the main chapel and the chapel outside the main entrance, which no longer survives. Writing in 1982, historian Jaroslav Folda noted that at the time there had been little investigation of Crusader frescoes that would provide a comparison for the fragmentary remains found at Krak des Chevaliers. Those in the chapel were painted on the masonry from the 1170–1202 rebuild. Mold, smoke, and moisture have made it difficult to preserve the frescoes. The fragmentary nature of the red and blue frescoes inside the chapel makes them difficult to assess. The one on the exterior of the chapel depicted the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple.[71]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Crac des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din, UNESCO, archived from the original on 2 December 2019, retrieved 8 November 2010

- ^ "UNESCO and Syrian government documents related to the monument site". Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Falk 2018, chapter 10, p.1

- ^ a b White 2014, p. 439

- ^ Aslanov 2012, p. 207

- ^ Setton & Hazard 1977, pp. 43, 152

- ^ Tschen-Emmons 2016, p. 149

- ^ Setton & Hazard 1977, p. 152

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. xv

- ^ Lepage 2002, p. 77

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 67

- ^ a b King 1949, p. 83

- ^ a b Kennedy 1994, pp. 145–146

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 62

- ^ a b c Salibi, Kamal S. (February 1973). "The Sayfās and the Eyalet of Tripoli 1579–1640". Arabica. 20 (1). Brill: 27. doi:10.1163/15700585-02001004. JSTOR 4056003. S2CID 247635304.

- ^ a b c Salibi 1977, p. 108

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 63

- ^ France 1997, p. 316

- ^ Spiteri 2001, p. 86

- ^ Boas 1999, p. 109

- ^ a b Nicholson 2001, pp. 3–4, 8–10

- ^ Barber 1995, pp. 34–35

- ^ a b Nicholson 2001, p. 11

- ^ Barber 1995, p. 83

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 146

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 1994, p. 150

- ^ Barber 1995, p. 202

- ^ Ellenblum 2007, p. 275

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 146–147

- ^ Nicholson 2001, p. 23

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 145

- ^ a b Kennedy 1994, p. 147

- ^ a b Kennedy 1994, pp. 152–153

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 147–148

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 148

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 148–150

- ^ King 1949, p. 92

- ^ a b King 1949, pp. 88–92

- ^ "Baybars' siege of 1271". Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ King 1949, p. 91

- ^ a b Folda, French & Coupel 1982, p. 179

- ^ Winter 2019, pp. 227–234

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 1

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 3

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 5–6

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 146, n. 4

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 6

- ^ Albright 1936, p. 167

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b Darke, Diane (2006). Syria. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-1-84162-162-3. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "General Census of Population and Housing 2004". Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) (in Arabic). Homs Governorate. 2004. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Eli; Robinson, Edward (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the Year 1838. Vol. 3. Crocker and Brewster. p. 181. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "Director-General of UNESCO appeals for protection of Syria's cultural heritage". UNESCO. United Nations. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (5 August 2012). "Robert Fisk: Syria's ancient treasures pulverised". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Latest victim of Syria air strikes: Famed Krak des Chevaliers castle". Middle East Online. 13 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Crac des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ DeVries 1992, p. 231

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 9

- ^ Boas 1999, p. 110

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 163

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 159

- ^ King 1949, p. 88

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 158–161, 163

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 161–162

- ^ Folda, French & Coupel 1982, pp. 178–179

- ^ Brown 2004, p. 62

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 156

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 153–156

- ^ a b King 1949, p. 87

- ^ a b Kennedy 1994, pp. 157–158

- ^ Folda, French & Coupel 1982, pp. 178–183

Works cited

[edit]- Albright, W. F. (1936), "Archaeological Exploration and Excavation in Palestine and Syria, 1935", American Journal of Archaeology, 40 (1), Archaeological Institute of America: 154–167, doi:10.2307/498307, JSTOR 498307, S2CID 191392990

- Aslanov, Cyril (2012). "Crusaders' Old French". In Arteaga, Deborah L (ed.). Research on Old French: The State of the Art. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-4768-5. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Barber, Malcolm (1995), The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55872-3

- Boas, Adrian J. (1999), Crusader Archaeology: The Material Culture of the Latin East, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17361-2

- Brown, R. Allen (2004) [1954], Allen Brown's English Castles, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, doi:10.1017/9781846152429, ISBN 978-1-84383-069-6

- DeVries, Kelly (1992), Medieval Military Technology, Hadleigh: Broadview Press, ISBN 978-0-921149-74-3

- Ellenblum, Roni (2007), Crusader Castles and Modern Histories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86083-3

- Falk, Avner (2018). Franks and Saracens: Reality and Fantasy in the Crusades. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-91392-1. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Folda, Jaroslav; French, Pamela; Coupel, Pierre (1982), "Crusader Frescoes at Crac des Chevaliers and Marqab Castle", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 36, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University: 177–210, doi:10.2307/1291467, JSTOR 1291467

- France, John (1997), Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-58987-1

- Kennedy, Hugh (1994), Crusader Castles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-42068-6

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1949), "The Taking of Le Krak des Chevaliers in 1271", Antiquity, 23 (90): 83–92, doi:10.1017/S0003598X0002007X, S2CID 164061795, archived from the original on 23 December 2012

- Lepage, Jean-Denis (2002), Castles and Fortified Cities of Medieval Europe: An Illustrated History, McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-1092-7

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2001), The Knights Hospitaller, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-0-85115-845-7

- Guillaume-Rey, Emmanuel (1871), Etudes sur les monuments de l'architecture militaire des Croisés en Syrie et dans l'ile de Chypre (in French), Paris: Impr. nationale

- Salibi, Kamal S. (1977), Syria Under Islam: Empire on Trial, 634–1097, Volume 1, Delmar: Caravan Books, ISBN 978-0-88206-013-2, archived from the original on 6 August 2023, retrieved 8 October 2016

- Setton, Kenneth M.; Hazard, Harry W., eds. (1977), A History of the Crusades, Volume V: The Art And Architecture of the Crusader, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-06820-2, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 5 September 2023

- Spiteri, Stephen (2001), Fortresses of the Knights, Malta: Book Distributors, ISBN 978-99909-72-06-1

- Tschen-Emmons, James B. (2016), Buildings and Landmarks of Medieval Europe, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-4408-4182-8, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 5 September 2023

- White, Richard (2014), "Krak des Chevaliers", in Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul; Ring, Trudy (eds.), International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa, Taylor & Francis, pp. 439–443, ISBN 978-1-134-25986-1, archived from the original on 23 September 2023, retrieved 5 September 2023

- Winter, Stefan (2019), "Le district de Ḥiṣn al-Akrād (Syrie) sous les Ottomans", Journal Asiatique, 307: 227–234, archived from the original on 8 April 2023, retrieved 8 March 2022

Further reading

[edit]- Deschamps, Paul (1934), Les Châteaux des Croisés en Terre Sainte I: le Crac des Chevaliers (in French), Paris

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Biller, Thomas (2006), Der Crac des Chevaliers. Die Baugeschichte einer Ordensburg der Kreuzfahrerzeit (in German), Regensburg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - République arabe syrienne (January 2005), Chateaux de Syrie: Dossier de Presentation en vue de l'inscription sur la Liste du Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO (PDF) (in French), UNESCO, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017, retrieved 26 December 2019

- Smail, R. C. (1973), The Crusaders in Syria and the Holy Land, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-02080-7

- Jean Mesqui and Maxime Goepp, Le Crac des Chevaliers (Histoire et architecture) [in French], Paris, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (AIBL) (coll. "Mémoires de l'AIBL"), 462 p. 890 ill., 2019 (presentation on the Academy website Archived 2021-06-29 at the Wayback Machine).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch