Dudley R. Herschbach

Dudley R. Herschbach | |

|---|---|

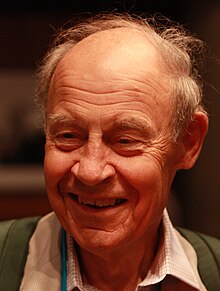

Herschbach in 2012 | |

| Born | Dudley Robert Herschbach June 18, 1932 San Jose, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Stanford University (BS, MS) Harvard University (MA, PhD) |

| Known for | Molecular dynamics |

| Awards | ACS Award in Pure Chemistry (1965) Linus Pauling Medal (1978) RSC Michael Polanyi Medal (1981) Irving Langmuir Award (1983) Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1986) National Medal of Science (1991) American Institute of Chemists Gold Medal (2011) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley Harvard University Freiburg University Texas A&M University |

| Doctoral advisor | Edgar Bright Wilson |

| Doctoral students | Richard N. Zare Seong Keun Kim Timothy Clark Germann |

Dudley Robert Herschbach (born June 18, 1932) is an American chemist at Harvard University. He won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Chemistry jointly with Yuan T. Lee and John C. Polanyi "for their contributions concerning the dynamics of chemical elementary processes".[1] Herschbach and Lee specifically worked with molecular beams, performing crossed molecular beam experiments that enabled a detailed molecular-level understanding of many elementary reaction processes. Herschbach is a member of the Board of Sponsors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Early life and education

[edit]Herschbach was born in San Jose, California on June 18, 1932.[2][3] The eldest of six children, he grew up in a rural area. He graduated from Campbell High School, where he played football. Offered both athletic and academic scholarships to Stanford University, Herschbach chose the academic. His freshman advisor, Harold S. Johnston, hired him as a summer research assistant, and taught him chemical kinetics in his senior year. His master's research involved calculating Arrhenius A-factors for gas-phase reactions.[4] Herschbach received a B.S. in mathematics in 1954 and an M.S. in chemistry in 1955 from Stanford University.[5]

Herschbach then attended Harvard University, where he earned an A.M. in physics in 1956 and a Ph.D. in chemical physics in 1958 under the direction of Edgar Bright Wilson. At Harvard, Herschbach examined tunnel splitting in molecules, using microwave spectroscopy.[4] He was awarded a three-year Junior Fellowship in the Society of Fellows at Harvard, lasting from 1957 to 1959.[6]

Research

[edit]In 1959, Herschbach joined the University of California at Berkeley, where he was appointed an assistant professor of chemistry and became an associate professor in 1961.[5] At Berkeley, he and graduate students George Kwei and James Norris constructed a cross-beam instrument large enough for reactive scattering experiments involve alkali and various molecular partners. His interest in studying elementary chemical processes in molecular-beam reactive collisions challenged an often-accepted belief that "collisions do not occur in crossed molecular beams". The results of his studies of K + CH3I were the first to provide a detailed view of an elementary collision, demonstrating a direct rebound process in which the KI product recoiled from an incoming K atom beam. Subsequent studies of K + Br2 resulted in the discovery that the hot-wire surface ionization detector they were using was potentially contaminated by previous use, and had to be pre-treated to obtain reliable results. Changes to the instrumentation yielded reliable results, including the observation that the K + Br2 reaction involved a stripping reaction, in which the KBr product scattered forward from the incident K atom beam. As the research continued, it became possible to correlate the electronic structure of reactants and products with the reaction dynamics.[4]

In 1963, Herschbach returned to Harvard University as a professor of chemistry. There he continued his work on molecular-beam reactive dynamics, working with graduate students Sanford Safron and Walter Miller on the reactions of alkali atoms with alkali halides. In 1967, Yuan T. Lee joined the lab as a postdoctoral student, and Herschbach, Lee, and graduate students Doug MacDonald and Pierre LeBreton began to construct a "supermachine" for studying collisions such as Cl + Br2 and hydrogen and halogen reactions.[4]

His most acclaimed work, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1986 with Yuan T. Lee and John C. Polanyi, was his collaboration with Yuan T. Lee on crossed molecular beam experiments. Crossing collimated beams of gas-phase reactants allows partitioning of energy among translational, rotational, and vibrational modes of the product molecules—a vital aspect of understanding reaction dynamics. For their contributions to reaction dynamics, Herschbach and Lee are considered to have helped create a new field of research in chemistry.[1] Herschbach is a pioneer in molecular stereodynamics, measuring and theoretically interpreting the role of angular momentum and its vector properties in chemical reaction dynamics.[4][7]

In the course of his life's work in research, Herschbach has published over 400 scientific papers.[8] Herschbach has applied his broad expertise in both the theory and practice of chemistry and physics to diverse problems in chemical physics, including theoretical work on dimensional scaling. One of his studies demonstrated that methane is, in fact, spontaneously formed at high-pressure and high-temperature environments such as those deep in the Earth's mantle; this finding is an exciting indication of abiogenic hydrocarbon formation, meaning that the actual amount of hydrocarbons available on Earth might be much larger than conventionally assumed under the assumption that all hydrocarbons are fossil fuels.[9] His recent work also includes a collaboration with Steven Brams studying approval voting.[10]

Science and education

[edit]

Hershbach's teaching ranges from graduate seminars on chemical kinetics to an introductory undergraduate course in general chemistry that he taught for many years at Harvard, and described as his "most challenging assignment".[5][11]

Herschbach has been a strong proponent of science education and science among the general public, and frequently gives lectures to students of all ages, imbuing them with his infectious enthusiasm for science and his playful spirit of discovery. Herschbach has also lent his voice to the animated television show The Simpsons for the episode "Treehouse of Horror XIV", where he is seen presenting the Nobel Prize in Physics to Professor Frink.[12]

In October 2010, Herschbach participated in the USA Science and Engineering Festival's Lunch with a Laureate program, where middle and high school students get to engage in an informal conversation with a Nobel Prize-winning scientist over a brown-bag lunch.[13] He is also a member of the Festival's advisory board.[14] Herschbach has participated in the Distinguished Lecture Series of the Research Science Institute (RSI), a summer research program for high school students held at MIT.[15]

Although still an active research professor at Harvard, he joined the Texas A&M University faculty September 1, 2005, as a professor of physics, teaching one semester per year in the chemical physics program.[16] As of 2010, he holds the title of professor emeritus at Harvard and remains well known for his involvement as a lecturer and mentor in the Harvard research community. He and his wife Georgene Herschbach also served for several years as the co-Masters of Currier House, where they were highly involved in undergraduate life in addition to their full-time duties.[4][6]

Public service

[edit]He is a board member of the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and was the chairman of the board for Society for Science & the Public from 1992 to 2010.[17] Herschbach is a member of the Board of Sponsors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.[18] In 2003 he was one of 22 Nobel Laureates who signed the Humanist Manifesto.[19]

He is also an Eagle Scout and recipient of the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award (DESA).[17][20]

Family

[edit]Herschbach's wife, Georgene Herschbach, served as the Associate Dean of Harvard College for Undergraduate Academic Programs.[21] Prior to retirement in 2009, she chaired Harvard College's influential Committee on Undergraduate Education.[22]

Awards and honors

[edit]Herschbach is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society and the Royal Chemical Society of Great Britain.[4] In addition to the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, he has received a wide variety of national and international awards. These include the National Medal of Science, the ACS Award in Pure Chemistry, the Linus Pauling Medal, the Irving Langmuir Award,[16] the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement,[23] and the American Institute of Chemists Gold Medal.[24]

Publications

[edit]- Herschbach, D. R. & V. W. Laurie. "Anharmonic Potential Constants and Their Dependence Upon Bond Length", University of California, Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, Berkeley, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission) (January 1961).

- Herschbach, D. R. "Reactive Collisions in Crossed Molecular Beams", University of California, Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, Berkeley, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission) (February 1962).

- Laurie, V. W. & D. R. Herschbach. "The Determination of Molecular Structure from Rotational Spectra", Stanford University, University of California, Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, Berkeley, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission) (July 1962).

- Zare, R. N. & D. R. Herschbach. "Proposed Molecular Beam Determination of Energy Partition in the Photodissociation of Polyatomic Molecules", University of California, Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, Berkeley, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission) (January 29, 1964).

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Press Release: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1986 Dudley R. Herschbach, Yuan T. Lee, John C. Polanyi". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Dudley Herschbach". dudley-herschbach.faculty.chemistry.harvard.edu. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "Dudley Robert Herschbach". www.chemistry.msu.edu. July 23, 2024 [July 23, 2024]. Archived from the original on July 23, 2024. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Farrar, James (1993). "1986 Nobel Laureate, Dudley R. Herschbach". In James, Laylin K. (ed.). Nobel laureates in chemistry 1901–1992. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 686–692. ISBN 978-0841226906.

- ^ a b c "Dudley R. Herschbach – Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Eliza M. (May 25, 2011). "Dudley Herschbach Nobel Prize Winner". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Dudley Herschbach: Chemical Reactions and Molecular Beams". DOE R&D Accomplishments. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Google Scholar search". Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Scott, H. P.; Hemley, R. J.; Mao, H.-k.; Herschbach, D. R.; Fried, L. E.; Howard, W. M.; Bastea, S. (2004). "Generation of methane in the Earth's mantle: In situ high pressure–temperature measurements of carbonate reduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (39): 14023–14026. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10114023S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405930101. PMC 521091. PMID 15381767.

- ^ Brams, Steven J.; Herschbach, DR (2001). "The Science of Elections". Science. 292 (5521): 1449. doi:10.1126/science.292.5521.1449. PMID 11379606. S2CID 28262658.

- ^ Herschbach, Dudley R. "The Scientist as Educator and Public Citizen: Linus Pauling and His Era". Oregon State University Libraries. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ^ Friedman, Claire G. (November 3, 2003). "Chem Professor Nets "Simpsons" Cameo". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Lunch with a Laureate". Usasciencefestival.org. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Advisors". Usasciencefestival.org. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Research Science Institute at MIT Hosts 81 High School Students". Center for Excellence in Education. June 24, 2013. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Hutchins, Shana (March 10, 2005). "Nobel Prize Winner to Join Physics Faculty". Science Texas A&M University. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Lupton, Neil (2004). "Scouts-L Youth Group List". Listerv. Retrieved June 1, 2006.

- ^ "Board of Sponsors". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Notable Signers". Humanism and Its Aspirations. American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Lupton, Neil (2005). "Scouts-L Youth Group List". Listerv. Retrieved June 1, 2006.

- ^ "Georgene Herschbach To Become Associate Dean of Harvard College". Harvard University Gazette. June 13, 1996. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ Mitchell, Robert (February 3, 2005). "Dingman, Herschbach take on new College roles". Harvard University Gazette.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "American Institute of Chemists Gold Medal". Science History Institute. March 22, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Dudley R. Herschbach on Nobelprize.org

- Video of a talk by Herschbach on Linus Pauling

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch