Glossary of cellular and molecular biology (0–L)

This glossary of cellular and molecular biology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts commonly used in the study of cell biology, molecular biology, and related disciplines, including genetics, biochemistry, and microbiology.[1] It is split across two articles:

- This page, Glossary of cellular and molecular biology (0–L), lists terms beginning with numbers and with the letters A through L.

- Glossary of cellular and molecular biology (M–Z) lists terms beginning with the letters M through Z.

This glossary is intended as introductory material for novices (for more specific and technical detail, see the article corresponding to each term). It has been designed as a companion to Glossary of genetics and evolutionary biology, which contains many overlapping and related terms; other related glossaries include Glossary of virology and Glossary of chemistry.

0–9

[edit]- 3' untranslated region (3'-UTR)

- 3'-end

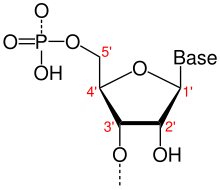

- One of two ends of a single linear strand of DNA or RNA, specifically the end at which the chain of nucleotides terminates at the third carbon atom in the furanose ring of deoxyribose or ribose (i.e. the terminus at which the 3' carbon is not attached to another nucleotide via a phosphodiester bond; in vivo, the 3' carbon is often still bonded to a hydroxyl group). By convention, sequences and structures positioned nearer to the 3'-end relative to others are referred to as downstream. Contrast 5'-end.

- 5' cap

- A specially altered nucleotide attached to the 5'-end of some primary RNA transcripts as part of the set of post-transcriptional modifications which convert raw transcripts into mature RNA products. The precise structure of the 5' cap varies widely by organism; in eukaryotes, the most basic cap consists of a methylated guanine nucleoside bonded to the triphosphate group that terminates the 5'-end of an RNA sequence. Among other functions, capping helps to regulate the export of mature RNAs from the nucleus, prevent their degradation by exonucleases, and promote translation in the cytoplasm. Mature mRNAs can also be decapped.

- 5' untranslated region (5'-UTR)

- 5-bromodeoxyuridine

- See bromodeoxyuridine.

- 5'-end

- One of two ends of a single linear strand of DNA or RNA, specifically the end at which the chain of nucleotides terminates at the fifth carbon atom in the furanose ring of deoxyribose or ribose (i.e. the terminus at which the 5' carbon is not attached to another nucleotide via a phosphodiester bond; in vivo, the 5' carbon is often still bonded to a phosphate group). By convention, sequences and structures positioned nearer to the 5'-end relative to others are referred to as upstream. Contrast 3'-end.

- 5-methyluracil

- See thymine.

A

[edit]- acentric

- (of a linear chromosome or chromosome fragment) Having no centromere.[2]

- acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA)

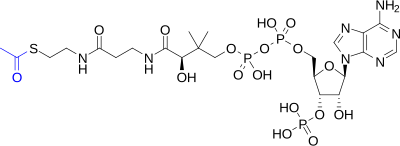

- A biochemical compound consisting of a coenzyme A molecule to which an acetyl group (–COCH

3) is attached via a high-energy thioester bond. Acetylation of coenzyme A occurs as part of the metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates (glycolysis), and fatty acids (beta oxidation), after which it participates as an energy carrier in several important biochemical pathways, notably the citric acid cycle, in which hydrolysis of the acetyl group releases energy which is ultimately captured in 11 ATP and one GTP. - acetylation

- The covalent attachment of an acetyl group (–COCH

3) to a chemical compound, protein, or other biomolecule via an esterification reaction with acetic acid, either spontaneously or by enzymatic catalysis. Acetylation plays important roles in several metabolic pathways and in histone modification. Contrast deacetylation. - acetyltransferase

- Any of a class of transferase enzymes which catalyze the covalent bonding of an acetyl group (–COCH

3) to another compound, protein, or biomolecule, a process known as acetylation. - acrocentric

- (of a linear chromosome or chromosome fragment) Having a centromere positioned very close to one end of the chromosome, as opposed to at the end or in the middle.[2]

- action potential

- The local change in voltage that occurs when the membrane potential of a specific location along the membrane of a cell rapidly depolarizes, such as when a nerve impulse is transmitted between neurons.

- activation

- See upregulation.

- activator

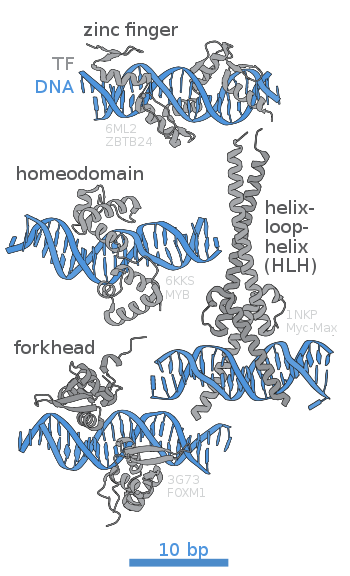

- A type of transcription factor that increases the transcription of a gene or set of genes. Most activators work by binding to a specific sequence located within or near an enhancer or promoter and facilitating the binding of RNA polymerase and other transcription machinery in the same region. See also coactivator; contrast repressor.

- active site

- The region of an enzyme to which one or more substrate molecules bind, causing the substrate or another molecule to undergo a chemical reaction. This region usually consists of one or more amino acid residues (commonly three or four) which, when the enzyme is folded properly, are able to form temporary chemical bonds with the atoms of the substrate molecule; it may also include one or more additional residues which, by interacting with the substrate, are able to catalyze a specific reaction involving the substrate. Though the active site constitutes only a small fraction of all the residues comprising the enzyme, its specificity for particular substrates and reactions is responsible for the enzyme's biological function.

- active transport

- Transport of a substance (such as a protein or drug) across a membrane against a concentration gradient. Unlike passive transport, active transport requires an expenditure of energy.

- adenine (A)

- A purine nucleobase used as one of the four standard nucleobases in both DNA and RNA molecules. Adenine forms a base pair with thymine in DNA and with uracil in RNA.

- adenosine (A)

- One of the four standard nucleosides used in RNA molecules, consisting of an adenine base with its N9 nitrogen bonded to the C1 carbon of a ribose sugar. Adenine bonded to deoxyribose is known as deoxyadenosine, which is the version used in DNA.

- adenosine diphosphate (ADP)

- adenosine monophosphate (AMP)

- adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

- An organic compound derived from adenine that functions as the major source of energy for chemical reactions inside living cells. It is found in all forms of life and is often referred to as the "molecular currency" of intracellular energy transfer.

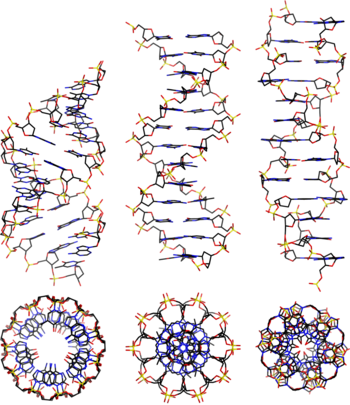

- A-DNA

- One of three main biologically active structural conformations of the DNA double helix, along with B-DNA and Z-DNA. The A-form helix has a right-handed twist with 11 base pairs per full turn, only slightly more compact than B-DNA, but its bases are sharply tilted with respect to the helical axis. It is often favored in dehydrated conditions and within sequences of consecutive purine nucleotides (e.g. GAAGGGGA); it is also the primary conformation adopted by double-stranded RNA and RNA-DNA hybrids.[3]

- affected relative pair

- Any pair of organisms which are related genetically and both affected by the same trait. For example, two cousins who both have blue eyes are an affected relative pair since they are both affected by the allele that codes for blue eyes.

- alkaline lysis

- A laboratory method used in molecular biology to extract and isolate extrachromosomal DNA such as the DNA of plasmids (as opposed to genomic or chromosomal DNA) from certain cell types, commonly cultured bacterial cells.

- allele

- One of multiple alternative versions of an individual gene, each of which is a viable DNA sequence occupying a given position, or locus, on a chromosome. For example, in humans, one allele of the eye-color gene produces blue eyes and another allele of the same gene produces brown eyes.

- allosome

- Any chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in size, form, or behavior and which is responsible for determining the sex of an organism. In humans, the X chromosome and the Y chromosome are sex chromosomes.

- alpha helix (α-helix)

- A common structural motif in the secondary structures of proteins consisting of a right-handed helix conformation resulting from hydrogen bonding between amino acid residues which are not immediately adjacent to each other.

- alternative splicing

- A regulated phenomenon of eukaryotic gene expression in which specific exons or parts of exons from the same primary transcript are variably included within or removed from the final, mature messenger RNA transcript. A class of post-transcriptional modification, alternative splicing allows a single gene to code for multiple protein isoforms and greatly increases the diversity of proteins that can be produced by an individual genome. See also RNA splicing.

- amber

- One of three stop codons used in the standard genetic code; in RNA, it is specified by the nucleotide triplet UAG. The other two stop codons are named ochre and opal.

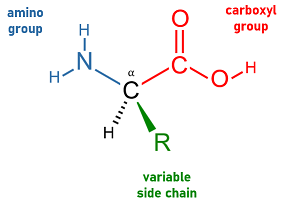

- amino acid

- Any of a class of organic compounds whose basic structural formula includes a central carbon atom bonded to amine and carboxyl functional groups and to a variable side chain. Out of nearly 500 known amino acids, a set of 20 are coded for by the standard genetic code and incorporated into long polymeric chains as the building blocks of peptides and hence of polypeptides and proteins. The specific sequences of amino acids in the polypeptide chains that form a protein are ultimately responsible for determining the protein's structure and function.

- amino terminus

- See N-terminus.

- aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

- Any of a set of enzymes which catalyze the transesterification reaction that results in the attachment of a specific amino acid (or a precursor) to one of its cognate transfer RNA molecules, forming an aminoacyl-tRNA. Each of the 20 different amino acids used in the genetic code is recognized and attached by its own specific synthetase enzyme, and most synthetases are cognate to several different tRNAs according to their specific anticodons.

- aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA)

- A transfer RNA to which a cognate amino acid is chemically bonded; i.e. the product of a transesterification reaction catalyzed by an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Aminoacyl-tRNAs bind to the aminoacyl site of the ribosome during translation.

- amplicon

- Any DNA or RNA sequence or fragment that is the source and/or product of an amplification reaction. The term is most frequently used to describe the numerous copied fragments that are the products of the polymerase chain reaction or ligase chain reaction, though it may also refer to sequences that are amplified naturally within a genome, e.g. by gene duplication.

- amplification

- The replication of a biomolecule, in particular the production of one or more copies of a nucleic acid sequence, known as an amplicon, either naturally (e.g. by spontaneous duplications) or artificially (e.g. by PCR), and especially implying many repeated replication events resulting in thousands, millions, or billions of copies of the target sequence, which is then said to be amplified.

- anaphase

- The stage of mitosis and meiosis that occurs after metaphase and before telophase, when the replicated chromosomes are segregated and each of the sister chromatids are moved to opposite sides of the cell.

- anaphase lag

- The failure of one or more pairs of sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes to properly migrate to opposite sides of the cell during anaphase of mitosis or meiosis due to a defective spindle apparatus. Consequently, both daughter cells are aneuploid: one is missing one or more chromosomes (creating a monosomy) while the other has one or more extra copies of the same chromosomes (creating a polysomy).

- aneucentric

- (of a linear chromosome or chromosome fragment) Having an abnormal number of centromeres, i.e. more than one.[4]

- aneuploidy

- The condition of a cell or organism having an abnormal number of one or more particular chromosomes (but excluding abnormal numbers of complete sets of chromosomes, which instead is known as euploidy).

- annealing

- The hybridization of two single-stranded nucleic acid molecules containing complementary sequences, creating a double-stranded molecule with paired nucleobases. The term is used in particular to describe steps in laboratory techniques such as polymerase chain reaction, where double-stranded DNA molecules are repeatedly denatured into single strands by heating and then exposed to cooler temperatures, causing the strands to reassociate with each other or with complementary primers. The exact temperature at which annealing occurs is strongly influenced by the length and specific sequence of the individual strands.

- antibody

- anticodon

- A series of three consecutive nucleotides within a transfer RNA which complement the three nucleotides of a codon within an mRNA transcript. During translation, each tRNA recruited to the ribosome contains a single anticodon triplet that pairs with its complementary codon from the mRNA sequence, allowing each codon to specify a particular amino acid to be added to the growing peptide chain. Anticodons containing inosine in the first position are capable of pairing with more than one codon due to a phenomenon known as wobble base pairing.

- antimetabolite

- Any molecule that functions as an antagonist to a metabolic process, limiting or inhibiting normal cellular metabolism; i.e. a metabolic poison.[4]

- antimitotic

- Any compound that suppresses normal mitosis in a cell or population of cells.[4]

- antioncogene

- A gene which helps to regulate cell growth and suppress tumors when functioning correctly, such that its absence or malfunction can result in uncontrolled cell growth and possibly cancer.[5] Compare oncogene.

- antiparallel

- The contrasting orientations of the two strands of a double-stranded nucleic acid (and more generally any pair of biopolymers) which are parallel to each other but with opposite directionality. For example, the two complementary strands of a DNA molecule run side-by-side but in opposite directions with respect to chemical numbering conventions, with one strand oriented 5'-to-3' and the other 3'-to-5'.

- antiporter

- A transport protein which works by exchanging two different ions or small molecules across a membrane in opposite directions, either at the same time or consecutively.[6]

- antisense

- See template strand.

- antisense RNA (asRNA)

- A single-stranded non-coding RNA molecule containing an antisense sequence that is complementary to a sense strand, such as a messenger RNA, with which it readily hybridizes, thereby inhibiting the sense strand's further activity (e.g. translation into protein). Many different classes of naturally occurring RNA such as siRNA function by this principle, making them potent gene silencers in various gene regulation mechanisms. Synthetic antisense RNA has also found widespread use in gene knockdown studies, and in practical applications such as antisense therapy.

- anucleate

- (of a cell or organism) Lacking a nucleus, i.e. a discrete, membrane-bound organelle enclosing the cell's genomic DNA, used especially of cells which normally have a nucleus but from which the nucleus has been removed (e.g. in artificial nuclear transfer), and also of specialized cell types that develop without nuclei despite that the cells of other tissues comprising the same organism ordinarily do have nuclei (e.g. mammalian erythrocytes).

- apical constriction

- The process by which contraction of the apical side of a cell (and often a corresponding expansion of the opposing basal side) causes the cell to assume a wedge-shaped morphology. The process is common during early development, where it is often coordinated across many adjacent cells of an epithelial layer simultaneously in order to generate bends or folds in developing tissues.

- apoptosis

- A highly regulated form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms.

- aptamer

- Any artificial DNA, RNA, or XNA oligonucleotide molecule, single-stranded or double-stranded, which functions as a ligand by binding selectively to one or more specific target molecules, usually other nucleic acids or proteins, and often a family of such molecules. The term is used in particular to describe short nucleic acid fragments which have been randomly generated and then artificially selected in vitro by procedures such as SELEX. Aptamers are useful in the laboratory as antibody mimetics, particularly in applications where conventional protein antibodies are not appropriate.

- artificial gene synthesis

- A set of laboratory methods used in the de novo synthesis of a gene (or any other nucleic acid sequence) from free nucleotides, i.e. without relying on an existing template strand.

- assimilatory process

- Any process by which chemical compounds containing biologically relevant elements (e.g. carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, selenium, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, molybdenum, etc.) are uptaken by microorganisms and incorporated into complex biomolecules in order to synthesize various cellular components. In contrast, a dissimilatory process uses the energy released by decomposing exogenous molecules to power the cell's metabolism and excretes residual or toxic compounds out of the cell, instead of reusing them to build new molecules.

- aster

- In animal cells, a star-shaped system of non-kinetochore microtubules that radiates from a centrosome or from either of the poles of the mitotic spindle during the early stages of cell division.[6]

- asynapsis

- The failure of homologous chromosomes to properly pair with each other during meiosis.[4] Contrast synapsis and desynapsis.

- attached X

- A single monocentric chromosome containing two or more physically attached copies of the normal X chromosome as a result of either a natural internal duplication or any of a variety of genetic engineering methods. The resulting compound chromosome effectively carries two or more doses of all genes and sequences included on the X, yet functions in all other respects as a single chromosome, meaning that haploid 'XX' gametes (rather than the ordinary 'X' gametes) will be produced by meiosis and inherited by progeny. In mechanisms such as genic balance in which the sex of an organism is determined by the total dosage of X-linked genes, an abnormal 'XXY' zygote, fertilized by one XX gamete and one Y gamete, will develop into a female.

- autolysis

- The lysis or digestion of a cell by its own enzymes; or of a particular enzyme by another instance of the same enzyme. See also autophagy.

- autosome

- Any chromosome that is not an allosome and hence is not involved in the determination of the sex of an organism. Unlike the sex chromosomes, the autosomes in a diploid cell exist in pairs, with the members of each pair having the same structure, morphology, and genetic loci.

- autozygote

- A cell or organism that is homozygous for a locus at which the two homologous alleles are identical by descent, both having been derived from a single gene in a common ancestor.[4] Contrast allozygote.

- auxesis

- The growth of a multicellular organism due to an increase in the size of its cells rather than an increase in the number of cells.

- axenic

- Describing a cell culture in which only a single species, variety, or strain is present, and which is therefore entirely free of contaminating organisms including symbiotes and parasites.

B

[edit]- B chromosome

- Any supernumerary nuclear DNA molecule which is not a duplicate of nor homologous to any of the standard complement of normal "A" chromosomes comprising a genome. Typically very small and devoid of structural genes, B chromosomes are by definition not necessary for life. Though they occur naturally in many eukaryotic species, they are not stably inherited and thus vary widely in copy number even between closely related individuals.[4]

- back mutation

- A mutation that reverses the effect of a previous mutation which had inactivated a gene, thus restoring wild-type function.[7] See also reverse mutation.

- bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)

- balancer chromosome

- base

- An abbreviation of nitrogenous base and nucleobase.

- base pair (bp)

- A pair of two nucleobases on complementary DNA or RNA strands which are loosely attracted to each other via hydrogen bonding, a type of non-covalent electrostatic interaction between individual atoms in the purine or pyrimidine rings of the complementing bases. This phenomenon, known as base pairing, is the mechanism underlying the hybridization that commonly occurs between nucleic acid polymers, allowing two single-stranded molecules to combine into a more energetically stable double-stranded molecule, as well as enabling certain individual strands to complement themselves. The ability of consecutive base pairs to stack one upon another contributes to the long-chain double helix structures observed in both double-stranded DNA and double-stranded RNA molecules.

- baseline

- A measure of the gene expression level of a gene or genes prior to a perturbation in an experiment, as in a negative control. Baseline expression may also refer to the expected or historical measure of expression for a gene.

- basic local alignment search tool (BLAST)

- A computer algorithm widely used in bioinformatics for aligning and comparing primary biological sequence information such as the nucleotide sequences of DNA or RNA or the amino acid sequences of proteins. BLAST programs enable scientists to quickly check for homology between two or more sequences by directly comparing the nucleotides or amino acids present at each position within each sequence; a common use is to search for matches between a specific query sequence and a digital sequence database such as a genome library, with the program returning a list of sequences from the database which resemble the query sequence above a specified threshold of similarity. Such comparisons can permit the identification of an organism from an unknown sample or the inference of evolutionary relationships between genes, proteins, or species.

- B-DNA

- The "standard" or classical structural conformation of the DNA double helix in vivo, thought to represent an average of the various distinct conformations assumed by very long DNA molecules under physiological conditions.[3] The B-form double helix has a right-handed twist with a diameter of 23.7 ångströms and a pitch of 35.7 ångströms or about 10.5 base pairs per full turn, such that each nucleotide pair is rotated 36° around the helical axis with respect to its neighboring pairs. See also A-DNA and Z-DNA.

- beta oxidation

- bidirectional replication

- A common mechanism of DNA replication in which two replication forks move in opposite directions away from the same origin; this results in a bubble-like region where the duplex molecule is locally separated into two single strands.[4]

- binary fission

- The separation of a single entity (e.g. a cell) into exactly two discrete entities closely resembling the original. The term refers in particular to a type of cell division used by prokaryotes such as bacteria, whereby a single parent cell divides evenly into two daughter cells which are genetically identical to each other and to the parent. Binary fission is preceded by replication of the parent cell's DNA, rapid growth of the cell wall, and various other processes which ensure even distribution of the cell's contents between the two progeny, but is generally a quicker and simpler process than the mitosis and cytokinesis that occur in eukaryotes.

- binding site

- bioassay

- Any analytical method that measures or qualifies the presence, effect, or potency of a substance within or upon a biological system, either directly or indirectly, e.g. by quantifying the concentration of a particular chemical compound within a sample obtained from living organisms, cells, or tissues, and ideally under controlled conditions that compare a sample subjected to an experimental treatment or manipulation with an unmanipulated sample, so as to permit inferences about the effect of the treatment upon some measured variable.[8]

- biochemical pathway

- bioenergetics

- biofilm

- A community of symbiotic microorganisms, especially bacteria, where cells produce and embed themselves within a slimy, sticky extracellular matrix composed of various high-molecular weight biopolymers, adhering to each other and sometimes also to a substratum, which may be a biotic or abiotic surface.[9] Many bacteria can exist either as independent single cells or switch to a physiologically distinct biofilm phenotype; those that create biofilms often do so in order to shelter themselves from harmful environments. Cells residing within biofilms can easily share nutrients and communicate, and subpopulations of cells may differentiate to perform specialized functions supporting the whole biofilm.[10]

- biomarker

- A measurable indicator of some biological state, especially a compound or biomolecule whose presence or absence in a biological system is a reliable sign of a normal or abnormal process, condition, or disease.[11] Things that may serve as biomarkers include direct measurements of the concentration of a particular compound or molecule in a tissue or fluid sample, or any other characteristic physiological, histological, or radiographic signal (e.g. a change in heart rate, or a distinct morphology under a microscope). They are regularly used as predictive or diagnostic tools in clinical medicine and laboratory research.

- biomolecular gradient

- Any difference in the concentration of biomolecules between two spaces within a biological system, whether intracellular, extracellular, across a membrane, or between different cells or different parts of a tissue or organ system. Gradients of one kind or another drive virtually all biochemical processes occurring within and between cells, as natural systems tend to move toward a thermodynamic equilibrium where concentrations are uniformly distributed in all spaces and no gradients exist. Gradients thus cause chemical reactions to occur in particular directions, which can be used by cells to accomplish essential biological functions, including metabolic energy transfer, signal transduction, and movement of ions and solutes into and out of cells and organelles. It is often necessary for cells to continuously regenerate gradients such as membrane potentials in order to permit these processes to continue.

- biomolecule

- Any molecule or chemical compound involved in or essential to one or more biological processes within a biological system, especially large macromolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates, but also broadly inclusive of smaller molecules such as vitamins, hormones, and biometals which are consumed or produced by biochemical reactions, often as part of biochemical pathways. Most biomolecules are organic compounds; some are produced naturally within cells or tissues (endogenous compounds), while others can only be obtained from the organism's environment (exogenous compounds).

- bivalent

- blast cell

- See precursor cell.

- blot

- Any of a variety of molecular biology methods by which electrophoretically or chromatographically separated DNA, RNA, or protein samples are transferred from a support medium such as a polyacrylamide or agarose gel onto an immobilizing carrier such as a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. Some methods involve the transfer of molecules by capillary action (e.g. Southern and northern blotting), while others rely on the transport of charged molecules by electrophoresis (e.g. western blotting). The transferred molecules are then visualized by colorant staining, by autoradiography, or by probing for specific sequences or epitopes with hybridization probes or antibodies conjugated to chemiluminescent reporters.[4]

- blunt end

- A term used to describe the end of a double-stranded DNA molecule where the terminal nucleobases on each strand are base-paired with each other, such that neither strand has a single-stranded "overhang" of unpaired bases; this is in contrast to a so-called "sticky end", where an overhang is created by one strand being one or more bases longer than the other. Blunt ends and sticky ends are relevant when ligating multiple DNA molecules, e.g. in restriction cloning, because sticky-ended molecules will not readily anneal to each other unless they have matching overhangs; blunt-ended molecules do not anneal in this way, so special procedures must be used to ensure that fragments with blunt ends are joined in the correct places.

- bromodeoxyuridine (BUDR, BrdU)

- A synthetic nucleoside analogue with a chemical structure similar to thymidine, the only difference being the substitution of a bromine atom for the methyl group of the nucleobase.

C

[edit]- cadastral gene

- A regulatory gene that restricts the expression of other genes to specific tissues or body parts in an organism, typically by producing gene products which variably inhibit or permit transcription of the other genes in different cell types.[4] The term is used most commonly in plant genetics.

- cadherin

- Any of a class of transmembrane proteins which are dependent on calcium ions (Ca2+) and whose extracellular domains function as mediators of cell–cell adhesion at adherens junctions in eukaryotic tissues.

- callus

- An unorganized mass of parenchymal cells that forms naturally at the site of wounds in plant tissues, and which is commonly artificially induced to form in plant tissue culture as a means of initiating somatic embryogenesis.[8]

- candidate gene

- A gene whose location on a chromosome is associated with a particular phenotype (often a disease-related phenotype), and which is therefore suspected of causing or contributing to the phenotype. Candidate genes are often selected for study based on a priori knowledge or speculation about their functional relevance to the trait or disease being researched.

- canonical sequence

- See consensus sequence.

- carbohydrate

- Any of a class of organic compounds having the generic chemical formula (CH

2O)

n, and one of several major classes of biomolecules found universally in biological systems. Carbohydrates include individual monosaccharides as well as larger polymeric oligosaccharides and polysaccharides, in which multiple monosaccharide monomers are joined by glycosidic bonds.[8] Abundant and ubiquitous, these compounds are involved in numerous essential biochemical processes and pathways; they are widely used as an energy source for cellular metabolism, as a form of energy storage, as signaling molecules, and as biomarkers to label or modify the activity of other molecules. Carbohydrates are often colloquially described as "sugars"; the prefix glyco- indicates a compound or process containing or involving carbohydrates, and the suffix -ose usually signifies that a compound is a carbohydrate or a derivative. - carboxyl terminus

- See C-terminus.

- carrier protein

- 1. A membrane protein that functions as a transporter, binding to a solute and facilitating its movement across the membrane by undergoing a series of conformational changes.[6]

- 2. A protein to which a specific ligand or hapten has been conjugated and which thereby carries an antigen capable of eliciting an antibody response.[12]

- 3. A protein which is included in an assay at high concentrations in order to prevent non-specific interactions of the assay's reagents with vessel surfaces, sample components, or other reagents.[12] For example, in many blotting techniques, albumin is intentionally allowed to bind non-specifically to the blotted membrane prior to fluorescent labelling, so as to "block" potential off-target binding of the fluorophore to the membrane, which might otherwise cause background fluorescence that obscures genuine signal from the target.

- caspase

- cassette

- A pre-existing nucleic acid sequence or construct, especially a DNA vector with an annotated sequence and precisely positioned regulatory elements, into which one or more fragments can be readily inserted or recombined by various genetic engineering methods. Recombinant plasmid vectors containing reliable promoters, origins of replication, and antibiotic resistance genes are commercially manufactured as cassettes to allow scientists to easily swap genes of interest into and out of an active "slot" or locus within the plasmid. See also multiple cloning site.

- CCAAT box

- A highly conserved regulatory DNA sequence located approximately 75 base pairs upstream (i.e. -75) of the transcription start site for many eukaryotic genes.[2]

- cDNA

- See complementary DNA.

- cell

- The basic structural and functional unit of which all living organisms are composed, essentially a self-replicating ball of protoplasm surrounded by a surface membrane which separates the interior from the external environment, thus providing a protected space in which the carefully controlled chemical reactions necessary to sustain biological processes can be carried out unperturbed. Unicellular organisms are composed of a single autonomous cell, whereas multicellular organisms consist of numerous cells cooperating together, with individual cells more or less specialized or differentiated to serve particular functions.[12] Cells vary widely in size, shape, and substructure, particularly between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The typical cell is microscopic, averaging 1 to 20 micrometres (μm) in diameter, though they may range in size from 0.1 μm to more than 20 centimetres in diameter for the eggs laid by some birds and reptiles, which are highly specialized single-celled ova.[8]

- cell biology

- The branch of biology that studies the structures, functions, processes, and properties of biological cells, the self-contained units of life common to all living organisms.

- cell compartmentalization

- The subdivision of the interior of a cell into distinct, usually membrane-bound compartments, including the nucleus and organelles (endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, chloroplasts, intracellular vesicles, etc.), a defining feature of the Eukarya.[8]

- cell cortex

- A specialized layer of cytoplasmic proteins lining the inner face of the cell membrane in most eukaryotic cells, composed primarily of actin microfilaments and myosin motor proteins and usually 100–1000 nanometres thick, which functions as a modulator of membrane behavior and cell surface properties.

- cell counting

- The process of determining the number of cells within a biological sample or culture by any of a variety of methods. Counting cells is an important aspect of cytometry used widely in research and clinical medicine. It is generally achieved by using a manual or digital cytometer to count the number of cells present in small fractions of a sample, and then extrapolating to estimate the total number present in the entire sample. The resulting quantification is typically expressed as a density or concentration, i.e. the number of cells per unit area or volume.

- cell culture

- The process by which living cells are grown and maintained, or "cultured", under carefully controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. Optimal growth conditions vary widely for different cell types but usually consist of a suitable vessel (e.g. a culture tube or Petri dish) containing a specifically formulated substrate or growth medium that supplies all of the nutrients essential for life (amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, etc.) plus any desirable growth factors and hormones, permits gas exchange (if necessary), and regulates the environment by maintaining consistent physico-chemical properties (temperature, pH, osmotic pressure, etc.). Some cell types require a solid surface to which they can adhere in order to reproduce, whereas others can be grown while floating freely in a liquid or gelatinous suspension. Most cells have a genetically determined reproduction limit, but immortalized cells will divide indefinitely if provided with optimal conditions.

- cell cycle

- cell division

- The separation of an individual parent cell into two daughter cells by any process. Cell division generally occurs by a complex, carefully structured sequence of events involving the reorganization of the parent cell's internal contents, the physical cleavage of the cytoplasm and plasma membrane, and the even distribution of contents between the two resulting cells, so that each ultimately contains approximately half of the original cell's starting material. It usually implies reproduction via the replication of the parent cell's genetic material prior to division, though cells may also divide without replicating their DNA. In prokaryotic cells, binary fission is the primary form of cell division. In eukaryotic cells, asexual division occurs by mitosis and cytokinesis, while specific cell types reserved for sexual reproduction can additionally divide by meiosis.[6]

- cell fusion

- The merging or coalescence of two or more cells into a single cell, as occurs in the fusion of gametes to form a zygote. Generally this occurs by the destabilization of each cell's plasma membrane and the formation of cytoplasmic bridges between them which then expand until the two cytoplasms are completely mixed; intercellular structures or organelles such as nuclei may or may not fuse as well. Some cells can be artificially induced to fuse with each other by treating them with a fusogen such as polyethylene glycol or by passing an electric current through them.[8]

- cell membrane

- The selectively permeable membrane surrounding all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, defining the outermost boundary of the cell and physically separating the cytoplasm from the extracellular environment.[13] Like all membranes, the cell membrane is a flexible, fluid, sheet-like phospholipid bilayer with membrane proteins, carbohydrates, and numerous other molecules embedded within or interacting with it from both sides. Embedded molecules often have freedom to move laterally alongside the membrane's lipids. Though the cell membrane can be freely crossed by many ions, small organic molecules, and water, most other substances require active transport through special pores or channels or by endocytosis or exocytosis in order to enter or exit the cell, especially very large or electrically charged molecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. Besides regulating the transport of substances into and out of the cell, the cell membrane creates an organized interior space in which to perform life-sustaining activities and plays fundamental roles in all of the cell's interactions with its environment, making it important in cell signaling, motility, defense, and division, among numerous other processes.

- cell physiology

- The study of the various biological activities and biochemical processes which sustain life inside cells, particularly (but not necessarily limited to) those related to metabolism and energy transfer, growth and reproduction, and the ordinary processes of the cell cycle.

- cell polarity

- The spatial variation within a cell, i.e. the existence of differences in shape, structure, or function between different parts of the same cell. Almost all cell types exhibit some form of polarity, often along an invisible axis which defines opposing sides or poles where the variation is most extreme. Having internal polarity permits cells to accomplish specialized functions such as signal transduction or to serve as epithelial cells which must perform different tasks on different sides, or facilitates cell migration or division.

- cell signaling

- The diverse set of processes by which cells transmit information to and receive information from themselves, other cells, or their environment. Signal transduction occurs in all cell types, prokaryotic and eukaryotic, and is of critical importance to the cell's ability to navigate and survive its physical surroundings. Countless mechanisms of signaling have evolved in different organisms, which are often categorized according to the proximity between sender and recipient (autocrine, intracrine, juxtacrine, paracrine, or endocrine).

- cell surface receptor

- Any of a class of receptor proteins embedded within or attached to the external surface of the cell membrane, with one or more binding sites facing the extracellular environment and one or more effector sites that couple the binding of a particular ligand to an intracellular event or process. Cell surface receptors are a primary means by which environmental signals are received by the cell and transmitted across the membrane into the cell interior. Some may also bind exogenous ligands and transport them into the cell in a process known as receptor-mediated endocytosis.[14]

- cell wall

- A tough, variously flexible or rigid layer of polysaccharide or glycoprotein polymers surrounding some cell types immediately outside of the cell membrane, including plant cells and most prokaryotes, which functions as an additional protective and selective barrier and gives the cell a definite shape and structural support. The chemical composition of the cell wall varies widely between taxonomic groups, and even between different stages of the cell cycle: in land plants it consists primarily of cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, while algae make use of carrageenan and agar, fungi use chitin, and bacterial cell walls contain peptidoglycan.

- cell-free DNA (cfDNA)

- Any DNA molecule that exists outside of a cell or nucleus, freely floating in an extracellular fluid such as blood plasma.

- cellular

- Of, relating to, consisting of, produced by, or resembling a cell or cells.

- cellular differentiation

- See differentiation.

- cellular immunity

- A class of immune response that does not rely on the production of antibodies but rather the activation of specific cell types such as phagocytes or cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, or the secretion of various cytokines from cells, in response to an antigen.

- cellular noise

- Any apparently random variability observed in quantities measured in cell biology, particularly those pertaining to gene expression levels.[15]

- cellular reprogramming

- The conversion of a terminally differentiated cell from one tissue-specific cell type to another. This involves dedifferentiation to a pluripotent state; an example is the conversion of mouse somatic cells to an undifferentiated embryonic state, which relies on the transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, Myc, and Klf4.[16]

- cellular senescence

- centimorgan (cM)

- A unit for measuring genetic linkage defined as the distance between chromosomal loci for which the expected average number of intervening chromosomal crossovers in a single generation is 0.01. Though not an actual measure of physical distance, it is used to infer the actual distance between two loci based on the apparent likelihood of a crossover occurring between them in any given meiotic division.

- central dogma of molecular biology

- A generalized framework for understanding the flow of genetic information between macromolecules within biological systems. The central dogma outlines the fundamental principle that the sequence information encoded in the three major classes of biopolymer—DNA, RNA, and protein—can only be transferred between these three classes in certain ways, and not in others: specifically, information transfer between the nucleic acids and from nucleic acid to protein is possible, but transfer from protein to protein, or from protein back to either type of nucleic acid, is impossible and does not occur naturally.

- centriole

- A cylindrical organelle composed of microtubules, present only in certain eukaryotes. A pair of centrioles migrate to and define the two opposite poles of a dividing cell where, as part of a centrosome, they initiate the growth of the spindle apparatus.

- centromere

- A specialized DNA sequence within a chromosome that links a pair of sister chromatids. The primary function of the centromere is to act as the site of assembly for kinetochores, protein complexes which direct the attachment of spindle fibers to the centromere and facilitate segregation of the chromatids during mitosis or meiosis.

- centromeric index

- The proportion of the total length of a chromosome encompassed by its short arm, typically expressed as a percentage; e.g. a chromosome with a centromeric index of 15 is acrocentric, with a short arm comprising only 15% of its overall length.[4]

- centrosome

- cfDNA

- See cell-free DNA.

- channel protein

- A type of transmembrane protein whose shape forms an aqueous pore in a membrane, permitting the passage of specific solutes, often small ions, across the membrane in either or both directions.[6]

- Chargaff's rules

- A set of axioms which state that, in the DNA of any chromosome, species, or organism, the total number of adenine (A) residues will be approximately equal to the total number of thymine (T) residues, and the number of guanine (G) residues will be equal to the number of cytosine (C) residues; accordingly, the total number of purines (A + G) will equal the total number of pyrimidines (T + C). These observations illustrate the highly specific nature of the complementary base-pairing that occurs in all duplex DNA molecules: even though non-standard pairings are technically possible, they are exceptionally rare because the standard ones are strongly favored in most conditions. Still, the 1:1 equivalence is seldom exact, since at any given time nucleobase ratios are inevitably distorted to some small degree by unrepaired mismatches, missing bases, and non-canonical bases. The presence of single-stranded DNA polymers also alters the proportions, as an individual strand may contain any number of any of the bases.

- charged tRNA

- A transfer RNA to which an amino acid has been attached; i.e. an aminoacylated tRNA. Uncharged tRNAs lack amino acids.[4]

- chDNA

- See chloroplast DNA.

- chemiosmosis

- chemokinesis

- A non-directional, random change in the movement of a molecule, cell, or organism in response to a chemical stimulus, e.g. a change in speed resulting from exposure to a particular chemical compound.

- chemotaxis

- A directed, non-random change in the movement of a molecule, cell, or organism in response to a chemical stimulus, e.g. towards or away from an area with a high concentration of a particular chemical compound.[6]

- chiasma

- A cross-shaped junction that forms the physical point of contact between two non-sister chromatids belonging to homologous chromosomes during synapsis. As well as ensuring proper segregation of the chromosomes, these junctions are also the breakpoints at which chromosomal crossover may occur during mitosis or meiosis, which results in the reciprocal exchange of DNA between the synapsed chromatids.

- chimerism

- The presence of two or more populations of cells with distinct genotypes in an individual organism, known as a chimera, which has developed from the fusion of cells originating from separate zygotes; each population of cells retains its own genome, such that the organism as a whole is a mixture of genetically non-identical tissues. Genetic chimerism may be inherited (e.g. by the fusion of multiple embryos during pregnancy) or acquired after birth (e.g. by allogeneic transplantation of cells, tissues, or organs from a genetically non-identical donor); in plants, it can result from grafting or errors in cell division. It is similar to but distinct from mosaicism.

- chloroplast

- A type of small, lens-shaped plastid organelle found in the cells of green algae and plants which contains light-sensitive photosynthetic pigments and in which the series of biochemical reactions that comprise photosynthesis takes place. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts are bound by a double membrane, contain their own internal circular DNA molecules from which they direct transcription of a unique set of genes, and replicate independently of the nuclear genome.[8][12]

- chloroplast DNA (cpDNA, chDNA, ctDNA)

- The set of DNA molecules contained within chloroplasts, a type of photosynthetic plastid organelle located within the cells of some eukaryotes such as plants and algae, representing a semi-autonomous genome separate from that within the cell's nucleus. Like other types of plastid DNA, cpDNA usually exists in the form of small circular plasmids.

- chondriome

- The complete set of mitochondria or of mitochondrial DNA within a cell, tissue, organism, or species.

- chromatid

- One copy of a newly copied chromosome, which is joined to the original chromosome by a centromere. Paired copies of the same individual chromosome are known as sister chromatids.

- chromatin

- A complex of DNA, RNA, and protein found in eukaryotic cells that is the primary substance comprising chromosomes. Chromatin functions as a means of packaging very long DNA molecules into highly organized and densely compacted shapes, which prevents the strands from becoming tangled, reinforces the DNA during cell division, helps to prevent DNA damage, and plays an important role in regulating gene expression and DNA replication.

- chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

- chromocenter

- A central amorphous mass of polytene chromosomes found in the nuclei of cells of the salivary glands in Drosophila larvae and resulting from the fusion of heterochromatic regions surrounding the centromeres of the somatically paired chromosomes, with the distal euchromatic arms radiating outward.[4]

- chromomere

- A region of a chromosome that has been locally compacted or coiled into chromatin, conspicuous under a microscope as a "bead", node, or dark-staining band, especially when contrasted with nearby uncompacted strings of DNA.

- chromosomal crossover

- chromosomal DNA

- DNA contained in chromosomes, as opposed to extrachromosomal DNA. The term is generally used synonymously with genomic DNA.

- chromosomal duplication

- The duplication of an entire chromosome, as opposed to a segment of a chromosome or an individual gene.

- chromosomal instability

- chromosome

- A nuclear DNA molecule containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. Chromosomes may be considered a sort of molecular "package" for carrying DNA within the nucleus of cells and, in most eukaryotes, are composed of long strands of DNA coiled with packaging proteins which bind to and condense the strands to prevent them from becoming an unmanageable tangle. Chromosomes are most easily distinguished and studied in their completely condensed forms, which only occur during cell division. Some simple organisms have only one chromosome made of circular DNA, while most eukaryotes have multiple chromosomes made of linear DNA.

- chromosome condensation

- The process by which eukaryotic chromosomes become shorter, thicker, denser, and more conspicuous under a microscope during prophase due to systemic coiling and supercoiling of chromatic strands of DNA in preparation for cell division.

- chromosome segregation

- The process by which sister chromatids or paired homologous chromosomes separate from each other and migrate to opposite sides of the dividing cell during mitosis or meiosis.

- chromosome walking

- See primer walking.

- cilium

- A slender, thread-like, membrane-bound projection extending from the surface of a eukaryotic cell, longer than a microvillus but shorter than a flagellum. Most eukaryotic cells have at least one primary cilium serving sensory or signaling functions; some cells employ thousands of motile cilia covering their entire surface in order to achieve locomotion or to move extracellular material past the cell.

- circular DNA

- Any DNA molecule, single-stranded or double-stranded, which forms a continuous closed loop without ends; e.g. bacterial chromosomes, mitochondrial and plastid DNA, as well as many other varieties of extrachromosomal DNA, including plasmids and some viral DNA. Contrast linear DNA.

- circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)

- Any extracellular DNA fragments derived from tumor cells which are circulating freely in the bloodstream.

- cis

- On the same side; adjacent to; acting from the same molecule. Contrast trans.

- cis-acting

- Affecting a gene or sequence on the same nucleic acid molecule. A locus or sequence within a particular DNA molecule such as a chromosome is said to be cis-acting if it influences or acts upon other sequences located within short distances (i.e. physically nearby, usually but not necessarily downstream) on the same molecule or chromosome; or, in the broadest sense, if it influences or acts upon other sequences located anywhere (not necessarily within a short distance) on the same chromosome of a homologous pair. Cis-acting factors are often involved in the regulation of gene expression by acting to inhibit or to facilitate transcription. Contrast trans-acting.

- cis-dominant mutation

- A mutation occurring within a cis-regulatory element (such as an operator) which alters the functioning of a nearby gene or genes on the same chromosome. Cis-dominant mutations affect the expression of genes because they occur at sites that control transcription rather than within the genes themselves.

- cisgenesis

- cis-regulatory element (CRE)

- Any sequence or region of non-coding DNA which regulates the transcription of nearby genes (e.g. a promoter, operator, silencer, or enhancer), typically by serving as a binding site for one or more transcription factors. Contrast trans-regulatory.

- cisterna

- Any of a class of flattened, membrane-bound vesicles or saccules of the smooth and rough endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus. By traveling through one or more cisternae, each of which contains a distinct set of enzymes, newly created proteins and polysaccharides undergo chemical modifications such as phosphorylation and glycosylation, which are used as packaging signals to direct their transport to specific destinations within the cell.[17]

- cistron

- citric acid cycle

- classical genetics

- The branch of genetics based solely on observation of the visible results of reproductive acts, as opposed to that made possible by the modern techniques and methodologies of molecular biology. Contrast molecular genetics.

- cleavage

- cleavage furrow

- A trough-like indentation in the surface of the parent cell, often conspicuous when viewed through a microscope, that initiates the cleavage of the cytoplasm (cytokinesis) as the contractile ring begins to narrow during cell division.

- clonal selection

- cloning

- The process of producing, either naturally or artificially, individual organisms or cells which are genetically identical to each other. Clones are the result of all forms of asexual reproduction, and cells that undergo mitosis produce daughter cells that are clones of the parent cell and of each other. Cloning may also refer to biotechnology methods which artificially create copies of organisms or cells, or, in molecular cloning, copies of DNA fragments or other molecules.

- closed chromatin

- See heterochromatin.

- coactivator

- A type of coregulator that increases the expression of one or more genes by binding to an activator.

- coding strand

- The strand of a double-stranded DNA molecule whose nucleotide sequence corresponds directly to that of the RNA transcript produced during transcription (except that thymine bases are substituted with uracil bases in the RNA molecule). Though it is not itself transcribed, the coding strand is by convention the strand used when displaying a DNA sequence because of the direct analogy between its sequence and the codons of the RNA product. Contrast template strand; see also sense.

- codon

- A series of three consecutive nucleotides in a coding region of a nucleic acid sequence. Each of these triplets codes for a particular amino acid or stop signal during protein synthesis. DNA and RNA molecules are each written in a language using four "letters" (four different nucleobases), but the language used to construct proteins includes 20 "letters" (20 different amino acids). Codons provide the key that allows these two languages to be translated into each other. In general, each codon corresponds to a single amino acid (or stop signal). The full set of codons is called the genetic code.

- codon usage bias

- The preferential use of a particular codon to code for a particular amino acid rather than alternative codons that are synonymous for the same amino acid, as evidenced by differences between organisms in the frequencies of the synonymous codons occurring in their coding DNA. Because the genetic code is degenerate, most amino acids can be specified by multiple codons. Nevertheless, certain codons tend to be overrepresented (and others underrepresented) in different species.

- coenocyte

- A multinucleate mass of cytoplasm bounded by a cell wall and resulting from continuous cytoplasmic growth and repeated nuclear division without cytokinesis, found in some species of algae and fungi, e.g. Vaucheria and Physarum.[8]

- coenzyme

- A relatively small, independent molecule which associates with a specific enzyme and participates in the reaction that the enzyme catalyzes, often by forming a covalent bond with the substrate. Examples include biotin, NAD+, and coenzyme A.[6]

- coenzyme A (CoA)

- cofactor

- Any non-protein organic compound capable of binding to or interacting with an enzyme. Cofactors are required for the initiation of catalysis.

- comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)

- competence

- complementarity

- A property of nucleic acid biopolymers whereby two polymeric chains or "strands" aligned antiparallel to each other will tend to form base pairs consisting of hydrogen bonds between the individual nucleobases comprising each chain, with each type of nucleobase pairing almost exclusively with one other type of nucleobase; e.g. in double-stranded DNA molecules, A pairs only with T and C pairs only with G. Strands that are paired in such a way, and the bases themselves, are said to be complementary. The degree of complementarity between two strands strongly influences the stability of the duplex molecule; certain sequences may also be internally complementary, which can result in a single strand binding to itself. Complementarity is fundamental to the mechanisms governing DNA replication, transcription, and DNA repair.

- complementary DNA (cDNA)

- DNA that is synthesized from a single-stranded RNA template (typically mRNA or miRNA) in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. cDNA is produced both naturally by retroviruses and artificially in certain laboratory techniques, particularly molecular cloning. In bioinformatics, the term may also be used to refer to the sequence of an mRNA transcript expressed as its DNA coding strand counterpart (i.e. with thymine replacing uracil).

- compound X

- See attached X.

- conditional expression

- The controlled, inducible expression of a transgene, either in vitro or in vivo.

- confluence

- In cell culture, a measure of the proportion of the surface area of a culture vessel that is covered by adherent cells, commonly expressed as a percentage. A culture in which the entire surface is completely covered by a continuous monolayer, such that all cells are immediately adjacent to and in direct physical contact with other cells, with no gaps or voids, is said to be 100-percent confluent. Different cell lines exhibit differences in growth rate or gene expression depending on the degree of confluence. Because of contact inhibition, most show a significant reduction in the rate of cell division as they approach complete confluence, though some immortalized cells may continue to divide, expanding vertically rather than horizontally by stacking themselves on top of the parent cells, until all available nutrients are depleted.[8][12]

- conformation

- The three-dimensional spatial configuration of the atoms comprising a molecule or macromolecular structure.[8] The conformation of a protein is the physical shape into which its polypeptide chains arrange themselves during protein folding, which is not necessarily rigid and may change with the protein's particular chemical environment.

- conformational change

- A change in the spatial conformation or physical shape of a molecule or macromolecule such as a protein or nucleic acid, rarely spontaneously but more commonly as a result of some alteration in the molecule's chemical environment (e.g. temperature, pH, salt concentration, etc.) or an interaction with another molecule. Changes in the tertiary structures of proteins can affect whether or how strongly they bind ligands or substrates; inducing these changes is a common means (both naturally and artificially) of activating, inactivating, or otherwise controlling the function of many enzymes and receptor proteins.[12]

- congression

- The movement of chromosomes to the spindle equator during the prometaphase and metaphase stages of mitosis.[4]

- consensus sequence

- A calculated order of the most frequent residues (of either nucleotides or amino acids) found at each position in a common sequence alignment and obtained by comparing multiple closely related sequence alignments.

- conservative replication

- A hypothetical mode of DNA replication in which the two parental strands of the original double-stranded DNA molecule ultimately remain hybridized to each other at the end of the replication process, with the two daughter strands forming their own separate molecule; hence one molecule is composed of both of the starting strands while the other is composed of the two newly synthesized strands. This is in contrast to semiconservative replication, in which each molecule is a hybrid of one old and one new strand. See also dispersive replication.

- conserved sequence

- A nucleic acid or protein sequence that is highly similar or identical across many species or within a genome, indicating that it has remained relatively unchanged through a long period of evolutionary time.

- constitutive expression

- 1. The continuous transcription of a gene, as opposed to facultative expression, in which a gene is only transcribed as needed. A gene that is transcribed continuously is called a constitutive gene.

- 2. A gene whose expression depends only on the efficiency of its promoter in binding RNA polymerase,[4] and not on any transcription factors or other regulatory elements which might promote or inhibit its transcription.

- contact inhibition

- In cell culture, the phenomenon by which most normal eukaryotic cells adhering to a planar substratum cease to grow and divide upon reaching a critical cell density, usually as they approach full confluence or come into physical contact with other cells. As a result, many types of cells cultured on plates or in Petri dishes will continue to proliferate until they cover the whole surface of the culture vessel, at which point the rate of cell division abruptly decreases or is arrested entirely, thus forming a confluent monolayer with minimal overlap between neighboring cells, even if the nutrient medium remains plentiful, rather than stacking themselves on top of each other.[14] Transformed or neoplastic cells tend not to respond to cell density in the same way and may continue to proliferate at high densities.[8] This type of density-dependent inhibition of growth is similar to and may occur simultaneously with, but is nonetheless distinct from, the related phenomenon of contact inhibition of movement,[12] whereby moving cells respond to physical contact by temporarily stopping and then reversing their direction of locomotion away from the point of contact.

- contig

- A continuous sequence of genomic DNA generated by assembling cloned fragments by means of their overlapping sequences.[7]

- cooperativity

- A phenomenon observed in some enzymes, receptor proteins, and protein complexes which have multiple binding sites, whereby the binding of a ligand to one or more sites apparently increases or decreases the affinity of one or more other binding sites for other ligands. This concept highlights the sensitive nature of the chemistry that governs interactions between biomolecules: the strength and specificity of interactions between protein and ligand are influenced, sometimes substantially, by nearby interactions (often conformational changes) and by the local chemical environment in general. Cooperativity is frequently invoked to account for the non-linearity of data resulting from attempts to measure the association/dissociation constants of particular protein–protein interactions.[12]

- copy DNA (cDNA)

- See complementary DNA.

- copy error

- A mutation resulting from a mistake made during DNA replication.[4]

- copy-number variation (CNV)

- A phenomenon in which sections of a genome are repeated and the number of repeats varies between individuals in the population, usually as a result of duplication or deletion events that affect entire genes or sections of chromosomes. Copy-number variations play an important role in generating genetic variation within a population.

- coregulator

- A protein that works together with one or more transcription factors to regulate gene expression.

- corepressor

- A type of coregulator that reduces (represses) the expression of one or more genes by binding to and activating a repressor.

- cosmid

- cpDNA

- See chloroplast DNA.

- CpG island

- A region of a genome in which CpG sites occur repetitively or with high frequency.

- CpG site

- A sequence of DNA in which a cytosine nucleotide is immediately followed by a guanine nucleotide on the same strand in the 5'-to-3' direction; the "p" in CpG refers simply to the intervening phosphate group linking the two consecutive nucleotides.

- CRISPR gene editing

- crista

- Any of numerous folds or invaginations in the inner mitochondrial membrane, which give this membrane its characteristic wrinkled shape and increase the surface area across which aerobic gas exchange and supporting electron transport reactions can occur. Cristae are studded with proteins such as ATP synthase and various cytochromes.

- crossing over

- See chromosomal crossover.

- crosslink

- Any chemical bond or series of bonds, normal or abnormal, natural or artificial, that connects two or more polymeric molecules to each other, creating an even larger, often structurally rigid and mechanically durable macromolecular complex. Crosslinks may consist of covalent, ionic, or intermolecular interactions, or even extensive physical entanglements of molecules, and may be reversible or irreversible; in polymer chemistry the term is often used to describe macrostructures that form predictably in the presence of a specific reagent or catalyst. In molecular biology the usage generally implies abnormal bonding (whether naturally occurring or experimentally induced) between different biomolecules (or different parts of the same biomolecule) which are ordinarily separate, especially nucleic acids and proteins. Crosslinking of DNA may occur between nucleobases on opposite strands of a double-stranded DNA molecule (interstrand), or between bases on the same strand (intrastrand), specifically via the formation of covalent bonds that are stronger than the hydrogen bonds of normal base pairing; these are common targets of DNA repair pathways. Proteins are also susceptible to becoming crosslinked to DNA or to other proteins through bonds to specific surface residues, a process which is artificially induced in many laboratory methods such as fixation and which can be useful for studying interactions between proteins in their native states. Crosslinks are generated by a variety of exogenous and endogenous agents, including chemical compounds and high-energy radiation, and tend to interfere with normal cellular processes such as DNA replication and transcription, meaning their persistence usually compromises cell health.

- ctDNA

- 1. An abbreviation of circulating tumor DNA.

- 2. An abbreviation of chloroplast DNA.

- C-terminus

- The end of a linear chain of amino acids (i.e. a peptide) that is terminated by the free carboxyl group (–COOH) of the last amino acid to be added to the chain during translation. This amino acid is said to be C-terminal. By convention, sequences, domains, active sites, or any other structure positioned nearer to the C-terminus of the polypeptide or the folded protein it forms relative to others are described as downstream. Contrast N-terminus.

- cut

- C-value

- The total amount of DNA contained within a haploid nucleus (e.g. a gamete) of a particular organism or species, expressed in number of base pairs or in units of mass (typically picograms); or, equivalently, one-half the amount in a diploid somatic cell. For simple diploid eukaryotes the term is often used interchangeably with genome size, but in certain cases, e.g. in hybrid polyploids descended from parents of different species, the C-value may actually represent two or more distinct genomes contained within the same nucleus. C-values apply only to genomic DNA, and notably exclude extranuclear DNA.

- C-value enigma

- A term used to describe a diverse variety of questions regarding the immense variation in nuclear C-value or genome size among eukaryotic species, in particular the observation that genome size does not correlate with the perceived complexity of organisms, nor necessarily with the number of genes they possess; for example, many single-celled protists have genomes containing thousands of times more DNA than the human genome. This was considered paradoxical until the discovery that eukaryotic genomes consist mostly of non-coding DNA, which lacks genes by definition. The focus of the enigma has since shifted to understanding why and how eukaryotic genomes came to be filled with so much non-coding DNA, and why some genomes have a higher gene content than others.

- cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)

- cyclosis

- See cytoplasmic streaming.

- cytidine (C, Cyd)

- One of the four standard nucleosides used in RNA molecules, consisting of a cytosine base with its N9 nitrogen bonded to the C1 carbon of a ribose sugar. Cytosine bonded to deoxyribose is known as deoxycytidine, which is the version used in DNA.

- cytochemistry

- The branch of cell biology involving the detection and identification of various cellular structures and components, in particular their localization within cells, using techniques of biochemical analysis and visualization such as chemical staining and immunostaining, spectrophotometry and spectroscopy, radioautography, and electron microscopy.

- cytogenetics

- The branch of genetics that studies how chromosomes influence and relate to cell behavior and function, particularly during mitosis and meiosis.

- cytokine

- Any of a broad and loosely defined class of small proteins and peptides which have functions in intercellular signaling (primarily autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine pathways), typically by interacting with specific receptors on the exterior surface of cells.[6]

- cytokinesis

- The final stage of cell division in both mitosis and meiosis, usually immediately following the division of the nucleus, during which the cytoplasm of the parent cell is cleaved and divided approximately evenly between two daughter cells. In animal cells, this process occurs by the closing of a microfilament contractile ring in the equatorial region of the dividing cell. Contrast karyokinesis.

- cytology

- The study of the morphology, processes, and life history of living cells, particularly by means of light and electron microscopy.[8] The term is also sometimes used as a synonym for the broader field of cell biology.

- cytolysis

- See lysis.

- cytometer

- cytomics

- The interdisciplinary field that studies cell biology, cytology, and biochemistry at the level of an individual cell by making use of single-cell molecular techniques and advanced microscopy to visualize the interactions of cellular components in vivo.[18]

- cytoplasm

- All of the material contained within a cell excluding (in eukaryotes) the nucleus;[6][12] i.e. that part of the protoplasm which is enclosed by the plasma membrane but separated from the nucleoplasm by the nuclear envelope, consisting of the fluid cytosol and the totality of its contents, including all of the cell's internal compartments, organelles, and substructures such as mitochondria, lysosomes, the endoplasmic reticulum, vesicles and inclusions, and a network of filamentous microtubules known as the cytoskeleton.[8] Some definitions of cytoplasm exclude certain organelles such as vacuoles and plastids. Composed of about 80 percent water, the numerous small molecules and macromolecular complexes dissolved or suspended within the cytoplasm give it characteristic viscoelastic and thixotropic properties, allowing it to behave variously as a gel or a liquid solution.[14] Though continuous throughout the intracellular space, the cytoplasm can often be resolved into distinct phases of different density and composition, such as an endoplasm and ectoplasm.[14] Most of the metabolic and biosynthetic activities of the cell take place in the cytoplasm, including protein synthesis by ribosomes. Despite their physical separation, the cytoplasm and the nucleus are mutually dependent upon each other, such that an isolated nucleus without cytoplasm is as incapable of surviving for long periods as is the cytoplasm without a nucleus.[14]

- cytoplasmic streaming

- The flow of the cytoplasm inside a cell, driven by forces exerted upon cytoplasmic fluids by the cytoskeleton. This flow functions partly to speed up the transport of molecules and organelles suspended in the cytoplasm to different parts of the cell, which would otherwise have to rely on passive diffusion for movement. It is most commonly observed in very large eukaryotic cells, for which there is a greater need for transport efficiency.

- cytoplast

- An enucleated eukaryotic cell; or all other cellular components besides the nucleus (i.e. the cell membrane, cytoplasm, organelles, etc.) considered collectively. The term is most often used in the context of nuclear transfer experiments, during which the cytoplast can sometimes remain viable in the absence of a nucleus for up to 48 hours.[14]

- cytosine (C)

- A pyrimidine nucleobase used as one of the four standard nucleobases in both DNA and RNA molecules. Cytosine forms a base pair with guanine.

- cytosol

- The soluble aqueous phase of the cytoplasm, in which small particles such as ribosomes, proteins, nucleic acids, and many other molecules are suspended or dissolved, excluding larger structures and organelles such as mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum.[8]

D

[edit]- daughter cell

- A cell resulting from the division of an initial progenitor, known as the parent cell. Generally two daughter cells are produced per division.[8]

- Denoising Algorithm based on Relevance network Topology

- An unsupervised algorithm that estimates an activity score for a pathway in a gene expression matrix, following a denoising step.[19]

- de novo mutation

- A spontaneous mutation in the genome of an individual organism that is new to that organism's lineage, having first appeared in a germ cell of one of the organism's parents or in the fertilized egg that develops into the organism; i.e. a mutation that was not present in either parent's genome.[4]

- de novo synthesis

- The assembly of a synthetic nucleic acid sequence from free nucleotides without relying on an existing template strand, i.e. de novo, by any of a variety of laboratory methods. De novo synthesis makes it theoretically possible to construct completely artificial molecules with no naturally occurring equivalent, and no restrictions on size or sequence. It is performed routinely in the commercial production of customized, made-to-order oligonucleotide sequences such as primers.

- deacetylation

- The removal of an acetyl group (–COCH

3) from a chemical compound, protein, or other biomolecule via hydrolysis of the covalent ester bond adhering it, either spontaneously or by enzymatic catalysis. Deacetylation is the opposite of acetylation. - decellularization

- degeneracy

- The redundancy of the genetic code, exhibited as the multiplicity of different codons that specify the same amino acid. For example, in the standard genetic code, the amino acid serine is specified by six unique codons (UCA, UCG, UCC, UCU, AGU, and AGC). Codon degeneracy accounts for the existence of synonymous mutations.

- degranulation

- The release of the contents of a secretory granule (usually antimicrobial or cytotoxic molecules) into an extracellular space by the exocytotic fusion of the granule with the cell's plasma membrane.[12]

- deletion

- A type of mutation in which one or more nucleotides are removed from a nucleic acid sequence.

- demethylation

- The removal of a methyl group (–CH