Gregorio Pietro Agagianian

Gregorio Pietro XV Agagianian Գրիգոր Պետրոս ԺԵ Աղաճանեան | |

|---|---|

| Cardinal Patriarch of Cilicia Prefect of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith | |

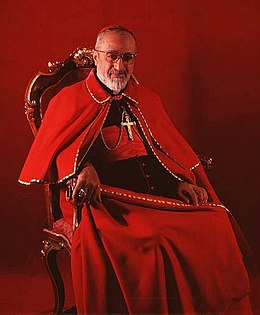

Photograph by David Lees, 1965 | |

| Church | Armenian Catholic Church |

| See | Cilicia |

| Appointed | 13 December 1937 |

| Term ended | 25 August 1962 |

| Predecessor | Avedis Bedros XIV Arpiarian |

| Successor | Ignatius Bedros XVI Batanian |

| Other post(s) | Cardinal-Bishop of Albano |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 23 December 1917 |

| Consecration | 21 July 1935 by Bishop Serge Der Abrahamian[1] |

| Created cardinal | 18 February 1946 by Pope Pius XII |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest (1946–1970) Cardinal-Bishop (1970–1971) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ghazaros Aghajanian 15 September 1895 |

| Died | 16 May 1971 (aged 75) Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Armenian (ethnicity) Lebanese (citizen) Vatican (citizen) Russian Empire (subject by birth)[a] |

| Denomination | Armenian Catholic |

| Residence | Rome, Beirut[b] |

| Motto | Iustitia et Pax (Justice and Peace) |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Sainthood | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Title as Saint | Servant of God |

| Styles of Gregorio Pietro Agagianian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Eminence |

| Spoken style | Your Eminence |

| Posthumous style | Servant of God |

| Informal style | Cardinal |

| See | Cilicia |

Gregorio Pietro XV Agagianian (ah-gah-JAHN-yan;[3] anglicized: Gregory Peter;[6] Western Armenian: Գրիգոր Պետրոս ԺԵ. Աղաճանեան,[7] Krikor Bedros ŽĒ. Aghajanian; born Ghazaros Aghajanian, 15 September 1895 – 16 May 1971) was an Armenian cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was the head of the Armenian Catholic Church (as Patriarch of Cilicia) from 1937 to 1962 and supervised the Catholic Church's missionary work for more than a decade, until his retirement in 1970. He was considered papabile on two occasions, in 1958 and 1963.

Educated in Tiflis and Rome, Agagianian first served as leader of the Armenian Catholic community of Tiflis before the Bolshevik takeover of the Caucasus in 1921. He then moved to Rome, where he first taught and then headed the Pontifical Armenian College until 1937 when he was elected to lead the Armenian Catholic Church, which he revitalized after major losses the church had experienced during the Armenian genocide.

Agagianian was elevated to the cardinalate in 1946 by Pope Pius XII. He was Prefect of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide) from 1958 to 1970. Theologically a moderate, a linguist, and an authority on the Soviet Union, he served as one of the four moderators at the Second Vatican Council. His cause for canonization was opened on 28 October 2022.[8]

Early life and priesthood

[edit]Agagianian[c] was born Ghazaros Aghajanian[d] on 15 September 1895, in the city of Akhaltsikhe, in the Tiflis Governorate of the Russian Empire (in present-day Samtskhe-Javakheti province of Georgia)[12][13][14] to Harutiun Aghajanian and Iskuhi Sarukhanian.[15] Around the time of his birth, around 60% of the city's 15,000 inhabitants were Armenians.[16] His family was part of the Armenian Catholic minority among the Javakheti Armenians, most of whom were followers of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[e] His ancestors had emigrated from Erzurum, fleeing Ottoman persecution, to the Russian Caucasus after the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829.[15]

His father died when he was five.[12][18][9] Agagianian said he "had been engaged in various small businesses."[12] He had a brother, Petros (Peter), who was a telegraph operator, and a sister, Elizaveta, the widow of an office worker, who both lived in the Soviet Union.[12] In 1962 his sister Elizaveta travelled to Rome through the intervention of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.[19]

Education and priesthood

[edit]Agagianian received primary education at the Karapetian School in Akhaltsikhe.[15] He later attended the Russian Orthodox Tiflis Seminary and then the Pontifical Urban University in Rome in 1906.[19][14] His outstanding performance in the latter was noted by Pope Pius X, who told the young Agagianian: "You will be a priest, a bishop, and a patriarch."[20] He was ordained priest in Rome on 23 December 1917.[13][1] Despite the upheaval brought by the Russian Revolution, he thereafter served as a parish priest in Tiflis (Tbilisi) and then as pastor of the city's Armenian Catholic community from 1919.[21][9] He left for Rome in 1921, after the Democratic Republic of Georgia was invaded by the Red Army.[19] He later said he was not confined by the Bolsheviks as "they had many other things to do."[21]

In late 1921, Agagianian became a faculty member and assistant rector of the Pontifical Armenian College in Rome. He later served as rector of the college from 1932 to 1937. He was also a faculty member of the Pontifical Urban University from 1922 to 1932.[19][13]

Agagianian was appointed titular bishop of Comana di Armenia on 11 July 1935, and was ordained bishop on 21 July 1935, at the San Nicola da Tolentino Church in Rome. His episcopal motto was Iustitia et Pax ("Justice and Peace").[1][22]

Armenian Catholic Patriarch

[edit]On 30 November 1937, Agagianian was elected Patriarch of Cilicia by the synod of bishops of the Armenian Catholic Church, an Eastern particular church sui iuris of the Catholic Church. The election received Papal assent on 13 December 1937.[19][1] He took the name Gregory Peter (French: Grégoire-Pierre; Armenian: Krikor Bedros) and became the 15th patriarch of the Armenian Catholic Church, which had 50,000 to 100,000 adherents.[5][23] All Armenian Catholic Patriarchs have Peter (Petros/Bedros) in their pontifical name as an expression of allegiance to the church founded by Saint Peter.[24]

According to Rouben Paul Adalian, the Armenian Catholic Church regained its stature in the Armenian diaspora under the "astute management" of Agagianian following the sizable losses in the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire.[25] As patriarch, he had immediate ecclesiastical jurisdiction over around 18,000 Catholic Armenians in Lebanon.[5] Agagianian reportedly played a key role in keeping the Armenian-populated village of Kessab within Syria when Turkey annexed the Hatay State in 1939 by intervening as a representative of the Vatican.[26]

According to historian Felix Corley, "One of the fiercest opponents of Communist rule in Armenia was the head of the Armenian Catholic community in Lebanon, Cardinal Bedros (Peter) Agagianian. In successive pastoral letters Agagianian attacked the Communists' record and spoke of the 'bitter reality and material misery' in Soviet Armenia."[27]

In 1950, Agagianian published a new pastoral letter in the journal Avetik in which he accused the Armenian Apostolic Church of breaking with its own past by rejecting the Council of Chalcedon and embracing what he termed the heresy of Miaphysitism. Agagianian also alleged, "The Catholic Armenian Apostolic Church is the only preserver of the holy faith and rites of our ancestors including Gregory the Illuminator."[28]

According to Felix Corley, opposition to Agagianian and his pastoral letter caused a rare moment of unity between the two divided factions of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Followers of both Kevork VI, the Pro-Soviet Catholicos of Etchmiadzin and Karekin I, the anti-communist and Armenian nationalist Catholicos of Cilicia in Antelias, finally, "had something to agree on in their condemnation of Agagianian". Among many other things, Agagianian was accused by Oriental Orthodox clergy of being "self-appointed" and having no lawful spiritual authority over the Armenian people. It is very telling, however, that "even on such a key matter", Catholicos-Patriarch Kevork VI had to file a written request with the Council of Ministers of the Armenian SSR and, "had to depend on the[ir] goodwill", even to be allowed to see the full text of Agagianian's pastoral letter.[29]

Agagianian inaugurated the Armenian Catholic church in Anjar, Lebanon in 1954[30] and founded a boarding house for orphaned boys there.[31]

He resigned the pastoral governance of the Armenian patriarchate on 25 August 1962, to focus on his duties at the Vatican.[1][19][32]

Cardinal

[edit]Agagianian was made a cardinal on 18 February 1946, by Pope Pius XII. He was appointed Cardinal-Priest of San Bartolomeo all'Isola on 22 February 1946.[1] Pope Pius, who had a "great interest in the Eastern churches", called on Agagianian to celebrate a pontifical Mass in the Armenian rite in the Sistine Chapel on 12 March 1946.[33] Herbert Matthews noted that it was Pope Pius's "desire to emphasize the universality of the Catholic Church".[34] Held in commemoration of the seventh anniversary of the Pope's coronation, it was the "first time any but the Latin rite has been used in the Sistine Chapel".[35]

Pius named him a member of the Holy Office in June 1958.[36]

Prefect of Propaganda Fide

[edit]

Agagianian was appointed Pro-Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide) on 18 June 1958, by Pope Pius.[1][5] Paul Hofmann of The New York Times wrote that Agagianian, an expert on communism and on Middle Eastern problems, was appointed because he "appeared particularly qualified to combat the danger of Communist inroads in missionary areas in the Middle East, Africa and all Asia".[5] He assumed the post on 23 June at a "simple ceremony".[37] He became Prefect of the Congregation on 18 July 1960.[1]

The Congregation, under his direction, controlled 25,000 missionary priests, 10,000 missionary lay brothers and more than 60,000 missionary nuns worldwide.[5] He had a staff of 27 and his jurisdiction included some 31 million Catholics, 3 million catechumens in 78 archdioceses, 197 apostolic vicariates, 114 prefectures, six independent abbeys, and three independent missions.[4] He supervised the training of Catholic missionaries all over the world.[38] According to Lentz, Agagianian was "largely responsible for liberalizing the church's policies in developing nations".[13]

Agagianian moved to live in Rome permanently in 1958,[5] but he travelled extensively to the missionary areas for which he was responsible.[39] On 10 December 1958, Agagianian presided over the First Far East Conference of Bishops at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, the Philippines with an attendance of 100 prelates, 10 papal representatives, 16 archbishops, 79 bishops from almost every country in the Far East.[40] He was Pope John's official representative at the 8 December ceremony for the consecration of the reconstructed Manila Cathedral.[41]

In February 1959 Agagianian visited Taiwan to oversee missionary work on the island. He later entrusted Archbishop Paul Yü Pin to reestablish the Fu Jen Catholic University there.[42] He arrived in Japan for a two-week long visit in May 1959, which included a meeting with Emperor Hirohito.[43]

His visit to Ireland in June 1961 was the highlight of the Patrician Year, when the 1,500th anniversary of Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, was celebrated.[44] Agagianian received a great popular welcome there.[45] Fianna Fáil President of Ireland Éamon de Valera was famously pictured kissing Agagianian's ring.[46][47] Agagianian celebrated a pontifical high mass in Dublin's Croke Park attended by more than 90,000 people.[48]

In September 1963 he met with Madame Nhu, the Catholic first lady of South Vietnam, in Rome.[49][50] On 18 October 1964, when the Uganda Martyrs were canonized by Pope Paul VI, Agagianian presided over the Holy Mass at Namugongo.[51] In November 1964 he traveled to Bombay, India to open the 38th Eucharistic Congress.[52] It was attended by more than 200 cardinals and bishops.[53]

Second Vatican Council

[edit]Agagianian sat on the Board of Presidency of the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II), which took place from 1962 to 1965. He was appointed by Pope Paul VI as one of the four moderators who directed the course of the debates,[54] along with Leo Joseph Suenens, Julius Döpfner, and Giacomo Lercaro.[55] Agagianian was the only one of these four from the Curia,[54] and represented the Eastern Catholic Churches.[56] He had a special role in the preparation of the missionary decree Ad gentes and Gaudium et spes, the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World.[57][58]

Papal candidate

[edit]As a cardinal, Agagianian participated in the papal conclaves of 1958 and 1963, during which he was considered to have been papabile.[f] According to J. Peter Pham, Agagianian was considered a "serious (albeit unwilling) candidate" for the papacy in both conclaves.[19] Contemporary news sources noted that Agagianian was the first serious non-Italian papal candidate in centuries.[59][14]

1958 conclave

[edit]According to Greg Tobin and Robert J. Wister, Agagianian, known to have been close to Pope Pius XII, was one of the favourites in the 1958 conclave.[60] His candidacy was widely discussed in the press.[61][62][63] Even before the death of Pope Pius XII, The Milwaukee Sentinel wrote that some authoritative voices of Vatican affairs believe that Agagianian was "without question the leading candidate" to succeed Pius.[64] On October 9, the day Pope Pius died, The Sentinel wrote that he is "considered by very responsible Vatican circles as the foremost choice" to succeed Pope Pius.[65] The Chicago Tribune noted that although Agagianian was popular amongst believers, the cardinals were expected to try first to agree on an Italian cardinal.[66]

The election was seen as a struggle between Italian Angelo Roncalli (who was eventually elected and became Pope John XXIII) and non-Italian Agagianian.[g] Agagianian came in second according to Massimo Faggioli and contemporary press reports.[69][68] Three months after the conclave, Roncalli revealed that his name and that of Agagianian "went up and down like two chickpeas in boiling water" during the conclave.[70] Armenian-American journalist Tom Vartabedian suggests that Agagianian may have been elected but declined the post.[71]

1963 conclave

[edit]According to John Whooley, an authority on the Armenian Catholic Church, Agagianian was considered "a strong contender, most 'papabile'" before the 1963 conclave and there was "much expectation" that he would be elected.[72] The conclave instead elected Giovanni Battista Montini, who became Pope Paul VI. According to the Armenian Catholic Church website, Agagianian was rumoured to have been actually elected at this conclave but declined to accept.[73] According to speculations by Italian journalists Andrea Tornielli (1993)[74][18] and Giovanni Bensi (2013)[75] Italian intelligence services were involved in preventing Agagianian from being elected pope in 1963. They maintain that SIFAR (Servizio informazioni forze armate), the Italian military intelligence service, mounted a smear campaign against Agagianian prior to the conclave by disseminating the narrative that Agagianian's 70-year-old sister, Elizaveta—who had visited Rome a year earlier to meet him—had ties with the Soviet authorities.[18] The Tablet wrote in 1963 that their meeting, which was preceded by negotiations partly conducted by the Italian ambassador in Moscow, "must rank as one of the best-kept diplomatic secrets of all time".[76]

Views

[edit]Thomas Rausch described him as "hardly a strict traditionalist."[56] According to Ralph M. Wiltgen, he was "regarded by the liberals as the most acceptable of the Curial cardinals" in the Second Vatican Council.[77] In 1963 Life magazine called him a liberal, cosmopolitan, and a moderate.[38][78] He was described as the Catholic Church's "topmost champion of the unity of the Christian churches under the Pope."[65] In 1950 he issued a pastoral letter in which he directly appealed to all Armenians (most of whom adhere to the Armenian Apostolic Church) to accept the authority of the Catholic Church.[79]

On the Soviet Union

[edit]During his lifetime, Agagianian was considered the Catholic Church's leading expert on communism and the Soviet Union.[13][80] Norman St John-Stevas wrote 1955 that Agagianian is "uncommitted" in the Cold War.[81] In a January 1958 diplomatic report Marcus Cheke, UK Ambassador to the Holy See, wrote that Agagianian "believes that the best thing for the Western powers to do is to hang on, avoid war (and the more strongly armed and united they are, the less danger there is of Russia venturing on a war) and to wait for a transformation inside Russia, which he thinks will happen sooner or later."[18] Agagianian called for a "heroically Christian" struggle against communism during his visit to Australia in 1959.[82]

Agagianian opposed the repatriation of Armenian Catholics from the Middle East to Soviet Armenia in 1946.[83] He noted that there was an intolerant environment in the Soviet Union towards religion and argued that "We [Armenian Catholics] are forced to remain as emigrants to preserve our church and faith".[84]

- Reception in the Soviet Union

Agagianian's statements regarding the repatriation of Armenians were received as defamation and hostile in the Soviet-controlled homeland.[84] In the early 1950s, Etchmiadzin, the Soviet-based official publication of the Armenian Apostolic Church, published articles severely criticizing Agagianian.[85][86] One article claimed that he was created cardinal in order to "damage the unity" and "disunite" the Armenian people. It also argued that Agagianian also held the "key to submitting the Oriental Orthodox churches of the Middle East (Coptic, Assyrian, Ethiopian, etc.) to the Catholic Church."[87] In another article, Agagianian was accused in "seek[ing] to bring Armenian believers under the control of the Vatican" and make them "anti-national [...] without an ideal and dignity [....] in short, a cosmopolitan crowd, which will serve the Turkish-American war machine."[88] After Stalin's death, relations improved. When Agagianian died, Vazgen I, head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, sent Pope Paul VI a letter mourning his death.[89]

Retirement and death

[edit]Agagianian effectively retired when he resigned as prefect on 19 October 1970, and was appointed Cardinal-Bishop of the Suburbicarian Diocese of Albano on October 22.[1][h]

Agagianian died of cancer in Rome on 16 May 1971.[91][22][9] Pope Paul VI called him a "noble figure" upon Agagianian's death.[92] His funeral took place on 21 May at St. Peter's Basilica.[7] He was buried in Rome's San Nicola da Tolentino Armenian church. A monument to Agagianian has been erected inside the church, flanked by the virgin martyr Hripsime and St. Vartan.[93]

Personal life

[edit]Agagianian was 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) tall and had a slender frame.[12] Since Agagianian spent much of his adult life in Rome, he was "Romanized"[67] and spoke fluent Italian[94] with a Roman accent.[21][59]

Agagianian was a polyglot and renowned linguist.[2][13] He was described as the College of Cardinals' "top linguist" in 1953.[95] He spoke fluent Armenian (his mother language),[12][2] Russian, Italian, French, English,[21] was proficient in Latin and Hebrew,[21] had a reading knowledge of Arabic,[21] and learned German, Spanish, classical Greek.[14] He had "a working knowledge of the Slavic languages and [could] speak most of the languages of the Middle and Far East."[65] Healy noted that "his English is excellent, touched with an unidentifiable accent that probably owes something to all his other languages".[21]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1966, Italian journalist Alberto Cavallari wrote that Agagianian is the "undisputed leader of non-European Catholicism. He is regarded by all as one of the most powerful cardinals in the Curia and is invested with autonomous powers equalled by none except the pope."[96] Healy argued that "he symbolize[d] the unity of the East and West in the Church"[3] Upon his death, The New York Times wrote that "Despite his failure to win election from the Sacred College of Cardinals, [Agagianian] nevertheless made a major impact on the development of the [Catholic] church and its role in the newly developing nations."[14]

Agagianian has been called "the most celebrated Armenian Catholic in history".[71] He was the second Armenian Catholic churchman ever to be made cardinal, after Andon Bedros IX Hassoun in 1880.[18] Richard McBrien noted that Agagianian was "regarded by some, including fellow Eastern-rite Catholics, as more Roman than the Romans".[97]

Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston called Agagianian "one of the most brilliant Churchmen of modern times, and possessor of one of the greatest minds in the history of the Church".[98] Norman St John-Stevas wrote of him in 1955 as "a man of distinguished presence, a fine scholar".[81] Healy opined that he exuded "an attractive combination of modesty and wisdom".[12]

Cause of beatification and canonization

[edit]Cardinal Angelo DeDonatis, Vicar General of His Holiness, issued a decree on 4 February 2020, officially commencing the process for Agagianian's beatification.[99] The cause was officially opened on October 28, 2022.[8]

Honours and awards

[edit]- Honorary Doctor of Laws from St. Francis Xavier University (1951)[100]

- Honorary Doctor of Letters from Fordham University (1951)[101]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from Boston College (1952)[11][102]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Santo Tomas (1958)[103]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Notre Dame (1960)[104]

- Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from Boston College (1960)[105]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from the Catholic University of America (1960)[106]

- Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from St. John's University (1960)[107]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from the National University of Ireland (1961)[108]

- State orders and awards

- Order of Merit of the Italian Republic – Knight (Cavaliere, 1963)[109]

Publications

[edit]- Agagianian, Gregorio Pietro (1970). Perché le missioni? Teologia della missione: studi e dibattiti (in Italian). Bologna: Ed. Nigrizia.

- Agagianian, Gregorio Pietro (1962). L'unità della Chiesa dal punto di vista teologico (in Italian). Milan: Vita e Pensiero.

- Agagianian, Gregorio Pietro (1950). La Romanità dell' Abbate Mechitar di Sebaste (in Italian). San Lazzaro degli Armeni.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "He was born a Russian subject [...] He now carries a Lebanese passport and will henceforth be a citizen of the Vatican."[2] "He is a globetrotter who travels on a Lebanese passport."[3]

- ^ "he has been dividing his time between Beirut, Rome and visits to Armenian communities in many parts of the world"[2] "...shuttling between Rome and his residence at Beirut."[4] "Cardinal Agagianian, who is in Rome on one of his periodical visits, will live here permanently."[5]

- ^ Agagianian Italian: [aɡadʒaˈnjan] is the Italianized version of his Armenian last name. The Armenian gh ʁ is replaced in Italian with a g ɡ and j is replaced with gi, both dʒ.

- ^ classical spelling: Ղազարոս Աղաջանեան, reformed: Ղազարոս Աղաջանյան,[9] Western Armenian: Ղազարոս Աղաճանեան.[10] His first name is sometimes transliterated as Gazaros and anglicized as Lazarus.[11]

- ^ In 1911 Malachia Ormanian estimated that Catholics comprised 10% of the 100,000 Armenians of Akhalkalaki and Akhaltsikhe uezds.[17]

- ^ "In 1958 Agagianian was one of four cardinals reported to have the best chance of being elected Pope. Today, at 65, he is still rated at the very top among the papabili — those cardinals regarded as likely to succeed Pope John."[3]

"In 1958 Agagianian was one of four cardinals reported to have the best chance of being elected Pope. Today, at 65, he is still rated at the very top among the papabili—those cardinals regarded as likely to succeed Pope John."[3]

"He was mentioned as a possibility in the 1958 conclave which elected John XXIII and again in the 1963 conclave which elected the present pope."[59] - ^ "The conclave had found itself choosing between the Armenian but Romanized Agagianian and the patriarch of Venice; it had chosen the latter: another Italian, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli..."[67] "The contest finally resolved itself, as so many people had predicted, into a straight-out issue between Italian Roncalli and non-Italian Agagianian."[68]

- ^ On February 11, 1965, Pope Paul VI decreed in his motu propio Ad Purpuratorum Patrum that Eastern Patriarchs who are elevated to the College of Cardinals would be made cardinal bishops and maintain their patriarchal see.[90] Since Agagianian was no longer patriarch, he remained a Cardinal-Priest with title to his titular church San Bartolomeo all'Isola. He only became Cardinal Bishop upon his appointment as the Cardinal-Bishop of Albano.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Grégoire-Pierre XV (François) Cardinal Agagianian †". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) () - ^ a b c d "Marked for Greatness: Gregory Peter XV Cardinal Agagianian". The New York Times. 19 June 1958.

- ^ a b c d e Healy 1961, p. 97.

- ^ a b Healy 1961, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hofmann, Paul (19 June 1958). "ARMENIAN HEADS VATICAN MISSIONS; Pontiff Nominates Cardinal Agagianian to Fill Role After Stritch's Death". The New York Times.

- ^ "Religion: Pius' Patriarch". Time. 25 March 1946.

...soft-voiced, fierce-bearded Gregory Peter XV Agagianian (pronounced ah-gah-jahn-yan), Patriarch-Catholicos of Cilicia of the Armenians...

- ^ a b Manjikian, Asbed (11 June 2014). ""Ազդակ"' Ութսունեօթը Տարիներու Ծառայութեան Ընդմէջէն. Անբասիր Հոգեւորականը' Կարտինալ Գրիգոր Պետրոս Ժե. Աղաճանեան". Aztag (in Armenian). Beirut. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) () - ^ a b "Armenian Catholic Church to begin canonization cause of Cardinal Agagianian on October 28". Shalom World. 30 August 2022. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Mchedlov, M. (1974). "Աղաջանյան Գրիգոր–Պետրոս [Aghajanian Grigor-Petros]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume I (in Armenian). p. 246.

- ^ ""Ազդակ"' Ութսունեօթը Տարիներու Ծառայութեան Ընդմէջէն. Անբասիր Հոգեւորականը' Կարտինալ Գրիգոր Պետրոս Ժե. Աղաճանեան". Aztag (in Armenian). 11 June 2014. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022.

- ^ a b "The Patriarch of Cilicia". The Heights. XXXIII (11). Boston College. 11 January 1952. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. (archived PDF

- ^ a b c d e f g Healy 1961, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f Lentz, Harris M. III (2009). "Agagianian, Gregory Peter XV". Popes and Cardinals of the 20th Century: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4766-2155-5.

- ^ a b c d e "Cardinal Agagianian Is Dead; Scholarly Mission Leader, 75". The New York Times. 17 May 1971.

- ^ a b c Poghosyan, L.A. (2019). "Հայազգի Հ կարդինալ Գրիգոր-Պետրոս ԺԵ Աղաջանյանի գործունեությունը մինչ հայ կաթողիկե եկեղեցու պատրիարքկաթողիկոս դառնալը [The Activities of the Armenian Cardinal Grigor-Petros XV Aghajanyan Before Becoming the Patriarkh-Catholicos of the Armenian Catholic Church]" (PDF). Region and the World (in Armenian) (4). Public Institute of Political and Sacial Research of Black Sea – Caspian Region. ISSN 1829-2437. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2022.

- ^ According to the Russian Empire Census of 1897. "Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку и уездам Российской Империи кроме губерний Европейской России. Ахалцихский уезд – г. Ахалцих [The first general census of the population of the Russian Empire in 1897. Population distribution according to the native language and counties of the Russian Empire, except for the provinces of European Russia. Akhaltsikhe district - Akhaltsikh]". Demoscope Weekly (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 September 2021.

- ^ Ormanian, Malachia (1911). Հայոց եկեղեցին և իր պատմութիւնը, վարդապետութիւնը, վարչութիւնը, բարեկարգութիւնը, արաողութիւնը, գրականութիւն, ու ներկայ կացութիւնը [The Church of Armenia: her history, doctrine, rule, discipline, liturgy, literature, and existing condition] (PDF) (in Armenian). Constantinople. p. 265. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Sanjian, Ara (21 January 2015). "An Armenian As Pope? – A British Diplomatic Report on Cardinal Agagianian, 1958". Horizon Weekly. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. (originally published in Window Quarterly, Volume V, No. 3 & 4, 1995; pp 11–13) PDF, archived

- ^ a b c d e f g Pham, John-Peter (2004). "Agagianian, Grégoire-Pierre XV". Heirs of the Fisherman: Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession. Oxford University Press. p. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-19-534635-0.

- ^ Gregory Cardinal Peter XV Agagianian (January 1961). "The Dogma of the Assumption in the Light of the First Seven Ecumenical Councils". Marian Library Studies (80). University of Dayton. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Healy 1961, p. 99.

- ^ a b "AGAGIANIAN, Grégoire-Pierre XV". cardinals.fiu.edu. Florida International University. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Cardinal Agagianian Succumbs". Times-News. via UPI. 15 May 1971.

- ^ Adalian 2010, p. 231.

- ^ Adalian 2010, p. 232.

- ^ Yengibaryan, G. (2012). "Քեսապի հայոց կաթոլիկ համայնքի պատմությունից [From the History of the Armenian Catholic Community in Kesap]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (4): 52.

- ^ Felix Corley (1996), Religion in the Soviet Union: An Archival Reader, New York University Press. Page 174.

- ^ Felix Corley (1996), Religion in the Soviet Union: An Archival Reader, New York University Press. Pages 175-175.

- ^ Felix Corley (1996), Religion in the Soviet Union: An Archival Reader, New York University Press. Pages 174-175.

- ^ "The Armenian Catholic Community of Anjar". ARF Anjar Committee. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021.

- ^ La Civita, Michael J.L. (3 March 2014). "Power of Grace". Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Armenian Patriarch Resigns". The New York Times. 26 August 1962.

- ^ Riccards, Michael P. (2012). Faith and Leadership: The Papacy and the Roman Catholic Church. Lexington Books. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-7391-7132-5.

- ^ Matthews, Herbert L. (20 February 1946). "Cardinal Delayed by Russians Flown to Rome by U.S. General". The New York Times.

- ^ "POPE ON ANNIVERSARY AT ARMENIAN SERVICE". The New York Times. 13 March 1946.

- ^ "POPE PIUS HONORS AGAGIANIAN AGAIN". The New York Times. 21 June 1958.

- ^ "AGAGIANIAN IN POST; Armenian Cardinal Succeeds to Office Given Stritch". The New York Times. 24 June 1958.

- ^ a b "The 'Papabili': One May Become Pope—Great Princes of the Church". Life. 14 June 1963. pp. 29–33.

The Curia's foremost authority on Russia is liberal, cosmopolitan Gregory Cardinal Agagianian, master of eight languages. As prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, he supervises the training of Catholic missionaries all over the world.

- ^ Whooley 2004, p. 422.

- ^ A. V. H. Hartendorp, ed. (January 1959). "The Government". Journal. XXXV (1). American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines: 14. (archived)

- ^ "Pope Names Agagianian Legate to the Far East". The New York Times. 23 November 1958.

- ^ Kuepers, Jac (2011). "The Re-establishment of Fu Jen University in Taiwan and the role of the SVD, in particular of Fr. Richard Arens" (PDF). fuho.fju.edu.tw. Fu Jen Catholic University. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2017.

- ^ "Chronology for 1959". nanzan-u.ac.jp. Nanzan University. p. 86. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "DUBLIN PAGEANTRY HONORS ST. PATRICK". The New York Times. 18 June 1961.

- ^ "I remember Cardinal Agagianian. I remember when he came to visit Ireland. The people gave him a great welcome." – According to journalist Gerard O'Connell who conducted interviews for the following book: Arinze, Francis (2006). "The Student Years in Rome and Ordination into the Priesthood (1955–1960)". God's Invisible Hand: The Life and Work of Francis Cardinal Arinze. Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-1-58617-135-3. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Sweeney, Ken (5 March 2010). "1961. . . a whole year of saints and shamrocks". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Photograph of de Valera kissing the ring of Cardinal Gregory Peter XV Agagianian, Papal Legate to the Patrician Congress". digital.ucd.ie. University College Dublin Digital Library. 25 June 1961. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021.

- ^ "CATHOLIC MEETING ENDS; Irish Rites Honor St. Patrick on 1,500th Anniversary". The New York Times. 26 June 1961.

- ^ "Mrs. Nhu, in Rome, Voices Confidence in U.S. Goodwill". The New York Times. 24 September 1963.

- ^ "No Audience With Pope". Ellensburg Daily Record. 23 September 1963. p. 2.

- ^ "Important Occasions". ugandamartyrsshrine.org.ug. Basilica of the Uganda Martyrs (Kampala Archdiocese, Uganda). Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "Cardinal Arrives In Bombay to Open Eucharist Meeting". The New York Times. 28 November 1964.

- ^ Brady, Thomas F. (29 November 1964). "CARDIAL OPENS BOMBAY CONGRESS'; 100,000 People Assemble for Eucharistic Session". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Nolan, Ann Michele (2006). A Privileged Moment: Dialogue in the Language of the Second Vatican Council, 1962–1965. Peter Lang. p. 83. ISBN 978-3-03910-984-5.

- ^ Gaillardetz, Richard (2006). The Church in the Making: Lumen Gentium, Christus Dominus, Orientalium Ecclesiarum. Paulist Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-8091-4276-7.

- ^ a b Rausch, Thomas P. (2016). "Roman Catholicism since 1800". In Sanneh, Lamin; McClymond, Michael (eds.). The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to World Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 610. ISBN 978-1-118-55604-7.

- ^ "Agagianian XV, Gregory Peter". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Gale. 2003.

He was a key figure at the Second Vatican Council, serving as a presiding officer and helping to draw up the missionary decree Ad Gentes.

- ^ Kalinichenko, E. V. (21 March 2008). "Агаджанян (Agadzhanyan)". Orthodox Encyclopedia (in Russian). Russian Orthodox Church.

Участвовал в подготовке и проведении Ватиканского II Собора, на к-ром был одним из четырех модераторов (председатель сессии), ему принадлежит особая роль в подготовке Конституции о Церкви в совр. мире "Gaudium et spes" (Радость и надежда) и декрета о миссионерской деятельности "Ad gentes divinitus" (Народам по Промыслу Божию).

- ^ a b c "Cardinal Agagianian Dies at 75". Reading Eagle. via UPI. 17 May 1971.

- ^ Tobin, Greg; Wister, Robert J. (2009). Selecting the Pope: Uncovering the Mysteries of Papal Elections. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4027-2954-6.

The favourites going in included the grandly named Cardinal Gregory Peter XV Agagianian, patriarch of Cilicia of the Armenians, a bearded sixty-three-year-old known to be close to Pius XII.

- ^ Hofmann, Paul (27 October 1958). "4 Are Leading Candidates, Sources at Vatican Believe". The New York Times.

- ^ Forcella, Enzo (11 October 1958). "Tre nomi di "papabili" Siri, Agagianian, Montini". La Stampa (in Italian).

- ^ "May Become Next Pope". Northern Star. Sydney. 12 March 1953.

An Armenian Cardinal who, according to widespread speculation in Australia and overseas, may become the next Pope...

- ^ Casserly, John J. (27 June 1958). "Cardinal Agagianian—Next Pope?". The Milwaukee Sentinel.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Casserly, John J. (9 October 1958). "Russian-born Cardinal Believed Top Choice as Pius XII Successor". The Milwaukee Sentinel.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Rue, Larry (28 October 1958). "Seal 2 Doors of Cardinals' Voting Area". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b Whooley 2004, p. 431.

- ^ a b "Papal Battle Voting Close". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 November 1958.

The three other contenders named by observers in their order of polling:

•Cardinal Agagianian... - ^ Faggioli, Massimo (2014). John XXIII: The Medicine of Mercy. Liturgical Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-8146-4976-3.

The runner-up was the Armenian cardinal Agagianian.

- ^ Hebblethwaite, Peter (2005). John XXIII: Pope of the Century. A & C Black. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-86012-387-3.

- ^ a b Vartabedian, Tom (6 February 2012). "The Armenian Cardinal and His Servant". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) () - ^ Whooley 2004, p. 423.

- ^ "Biography of Gregory Petros XV Agagianian". Armenian Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Move to Block Soviet Pope Revealed". The Buffalo News. 21 December 1993. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017.

- ^ Bensi, Giovanni (20 March 2013). "Le due chance perdute del papa armeno". East Journal (in Italian).; also published in Russian: Bensi, Giovanni (20 March 2013). "Операция "Конклав" (Operation "Conclave")". Nezavisimaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- ^ "Cardinal Agagianian Reunited with His Sister". The Tablet. 6 July 1963. p. 746.

- ^ Wiltgen, Ralph M. (1991). The Inside Story of Vatican II: A Firsthand Account of the Council's Inner Workings. TAN Books. ISBN 978-1-61890-639-7.

- ^ Kaiser, Robert B. (21 June 1963). "And Now the Search Begins for the New Pope". Life. p. 57.

There is Gregory Peter Agagianian, 67, a bearded Armenian cardinal who has been a Roman by adoption since he left his home town when he was 11 year old. Agagianian is a moderate who has traveled widely in his capacity as head of all the Church's missionary activity. However, he holds no sympathy for the Church's revisionist theologians and biblical scholars, and this may prevent the more moderate cardinals from voting for him.

- ^ Tchilingirian, Hratch (9 June 2016). "L'Eglise arménienne pendant la guerre froide : la crise Etchmiadzine-Antelias" (PDF). Hebdo Nor Haratch (in French) (265). Paris: 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2017.

- ^ "Cardinal Dies; Was Authority on Communism". The Day. via AP. 17 May 1971.

- ^ a b Norman St John-Stevas (22 September 1955). "The Next Pope". The Spectator. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Duncan, Bruce (2001). Crusade Or Conspiracy?: Catholics and the Anti-Communist Struggle in Australia. UNSW Press. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-86840-731-9.

- ^ Whooley, John (2016). "The Armenian Catholic Church in the Middle East – Modern History, Ecclesiology and Future Challenges". The Downside Review. 134 (4): 137. doi:10.1177/0012580616671061. S2CID 157659811.

- ^ a b Stepanyan, Armenuhi (2010). "Հայրենադարձության հայկական փորձը (1946–1948 թթ.) [Armenian Experience of Repatriation (1946–1948)]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1): 151.

- ^ Borchanian, F. (1952). "Երկու խոսք կարդինալ Աղաջանյանի ազգադավ գործունեության մասին [Two words on Cardinal Agagianian's anti-national activity]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 9 (4). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin: 24–27.

- ^ Editorial board (1953). "Օրմանյան պատրիարքի "Հայոց Եկեղեցին" և կարդինալ Աղաջանյանը ["Armenian Church" by Patriarch Ormanian and Cardinal Agagianian]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 10 (2). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin: 3–9.

- ^ "Կարդինալ Աղաջանյանի այցելությունը [Cardinal Agagianian's visit]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 8 (11–12). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin: 79–80. 1951.

- ^ "Կարդինալ Աղաջանյանը և իր գործունեությունը [Cardinal Agagianian and his activities]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 9 (3). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin: 52–55. 1952.

- ^ "Ամենայն Հայոց Վեհափառ Հայրապետի ցավակցական հեռագիրը Նորին Սրբություն Պողոս Զ Սրբազան Պապին՝ կարդինալ Գրիգոր Աղաջանյանի մահվան առթիվ, և պատասխանը". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 28 (5). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin: 9. 1971.

- ^ Pope Paul VI (11 February 1965). "Ad purpuratorum Patrum Collegium" (in Italian). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "Morto a Roma a 75 anni: Il cardinale Agagianian fu a scuola con Stalin". La Stampa (in Italian). 17 May 1971. p. 27.

- ^ Caprile, G. "Morte del Card. Agagianian". La Civiltà Cattolica (in Italian) (2899–2904): 596.

- ^ Hager, June (June 1999). "The Armenian Catholic Community in Rome". Inside the Vatican. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Brewer, Sam Pope (19 February 1946). "32 NEW CARDINALS NOTIFIED OF TITLES IN VATICAN RITES". The New York Times.

...Cardinal Agagianian delivered a half-hour speech in fluent Italian...

- ^ "Will the next Pope be a Russian?". The Milwaukee Sentinel. 25 April 1953.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Cavallari, Alberto (1967). The Changing Vatican [Il Vaticano che cambia]. Doubleday. p. 156.

- ^ McBrien, Richard (21 December 2009). "Pope John XXIII had positive impact on present, future church". catholiccourier.com. Roman Catholic Diocese of Rochester.

- ^ Healy 1961, pp. 97–98.

- ^ "The canonization process of Armenian Cardinal Agagianian opens on October 28th". Agenzia Fides. 29 August 2022. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023.

- ^ "Cardinal Agagianian Honored". The New York Times. 5 December 1951.

- ^ "CATHOLIC LEADER GREETED; Cardinal Agagianian Welcomed by Armenian Community". The New York Times. 14 December 1951.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded by Boston College 1952–1998" (PDF). bc.edu. p. 102. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Awardees of the University". ust.edu.ph. University of Santo Tomas.

- ^ "For release in AM's, Thursday, May 12th" (PDF). University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2017.

- ^ "Cardinal Agagianian Accepts Degree". 885. VIII (6). Newton College of the Sacred Heart. 1 June 1960.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Conferred by The Catholic University of America" (PDF). cua.edu. Catholic University of America.

- ^ "Cardinal Agagianian Honored by St. John's". St. John's University Alumni News. 1 (6). St. John's University: 1. June 1960.

- ^ "NUI Honorary Degrees Awarded" (PDF). nui.ie. National University of Ireland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2017.

- ^ "AGAGIANIAN S.Em. Rev.ma il Cardinale Gregorio Pietro". quirinale.it (in Italian). President of Italy. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- Whooley, John (October 2004). "The Armenian Catholic Church: A Study in History and Ecclesiology". The Heythrop Journal. 45 (4): 416–434. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2265.2004.00264.x.

- Healy, Paul F. (July 1961). "The Gentle Armenian". Catholic Digest: 97-103.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch