Hieratic

| Hieratic | |

|---|---|

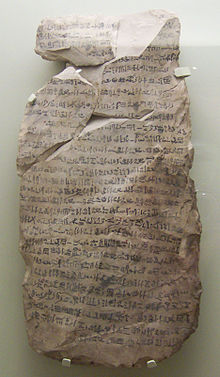

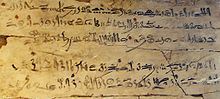

Transcribed papyrus, c. 1500 BC | |

| Script type | with consonants |

Time period | c. 3200 BC – 3rd century AD |

| Direction | Mixed |

| Languages | Egyptian language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems | Demotic possibly inspired Byblos syllabary |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Egyh (060), Egyptian hieratic |

| Unicode | |

| U+13000–U+1342F (unified with Egyptian hieroglyphs) | |

Hieratic (/haɪəˈrætɪk/; Ancient Greek: ἱερατικά, romanized: hieratiká, lit. 'priestly') is the name given to a cursive writing system used for Ancient Egyptian and the principal script used to write that language from its development in the third millennium BCE until the rise of Demotic in the mid-first millennium BCE. It was primarily written in ink with a reed brush on papyrus.[1]

Etymology

[edit]In the second century, the term hieratic was used for the first time by the Greek scholar Clement of Alexandria to describe this Ancient Egyptian writing system.[2] The term derives from the Greek for 'priestly writing' (Koinē Greek: γράμματα ἱερατικά) because at that time, for more than eight and a half centuries, hieratic had been used traditionally only for religious texts and literature.

Hieratic can also be an adjective meaning 'of or associated with sacred persons or offices; sacerdotal'.[3]

Development

[edit]Hieratic developed as a cursive form of hieroglyphic script in the Naqada III period of Ancient Egypt, roughly 3200–3000 BCE.[4] Although handwritten printed hieroglyphs continued to be used in some formal situations, such as manuscripts of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, noncursive hieroglyphic script became largely restricted to monumental inscriptions.

Around 650 BCE, the even more-cursive Demotic script developed from hieratic.[1] Demotic arose in northern Egypt and replaced hieratic and the southern shorthand known as abnormal hieratic for most mundane writing, such as personal letters and mercantile documents. Hieratic continued to be used by the priestly class for religious texts and literature into the third century AD.

Uses and materials

[edit]

Through most of its long history, hieratic was used for writing administrative documents, accounts, legal texts, and letters, as well as mathematical, medical, literary, and religious texts. During the Greco-Roman period, when Demotic, and later, Greek, had become the chief administrative script, hieratic was limited primarily to religious texts. In general, hieratic was much more important than hieroglyphs throughout Egypt's history, being the script used in daily life. It was also the writing system first taught to students, knowledge of hieroglyphs being limited to a small minority who were given additional training.[5] It is often possible to detect errors in hieroglyphic texts that came about due to a misunderstanding of an original hieratic text.

Most often, hieratic script was written in ink with a reed brush on papyrus, wood, stone, or pottery ostraca. During the Roman period, reed pens (calami) were also used. Thousands of limestone ostraca have been found at the site of Deir al-Madinah, revealing an intimate picture of the lives of common Egyptian workers. Besides papyrus, stone, ceramic shards, and wood, there are hieratic texts on leather rolls, although few have survived. There are also hieratic texts written on cloth, especially on linen used in mummification. There are some hieratic texts inscribed on stone, a variety known as lapidary hieratic. These are particularly common on stelae from the twenty-second dynasty.

During the late sixth dynasty, hieratic was sometimes incised into mud tablets with a stylus, similar to cuneiform. About five hundred of these tablets have been discovered in the governor's palace at Ayn Asil (Balat),[6] and a single example was discovered from the site of Ayn al-Gazzarin, both in the Dakhla Oasis.[7][8][9] At the time the tablets were made, Dakhla was located far from centers of papyrus production.[10] These tablets record inventories, name lists, accounts, and approximately fifty letters. Of the letters, many are internal letters that were circulated within the palace and the local settlement, but others were sent from other villages in the oasis to the governor.

Characteristics

[edit]

Hieratic script, unlike inscriptional and manuscript hieroglyphs, reads from right to left. Initially, hieratic could be written in either columns or horizontal lines, but after the twelfth dynasty (specifically during the reign of Amenemhat III), horizontal writing became the standard.

Hieratic is noted for its cursive nature and use of ligatures for a number of characters. Hieratic script also uses a much more standardized orthography than hieroglyphs; texts written in the latter often had to take into account extra-textual concerns, such as decorative uses and religious concerns that were not present in, say, a tax receipt. There are also some signs that are unique to hieratic, although Egyptologists have invented equivalent hieroglyphic forms for hieroglyphic transcriptions and typesetting.[11] Several hieratic characters have diacritical additions so that similar signs could easily be distinguished.

Hieratic is often present in any given period in two forms, a highly ligatured, cursive script used for administrative documents, and a broad uncial bookhand used for literary, scientific, and religious texts. These two forms can often be significantly different from one another. Letters, in particular, used very cursive forms for quick writing, often with large numbers of abbreviations for formulaic phrases, similar to shorthand.

A highly cursive form of hieratic known as "Abnormal Hieratic" was used in the Theban area from the second half of the twentieth dynasty until the beginning of the twenty-sixth dynasty.[12][13] It derives from the script of Upper Egyptian administrative documents and was used primarily for legal texts, land leases, letters, and other texts. This type of writing was superseded by Demotic—a Lower Egyptian scribal tradition—during the twenty-sixth dynasty, when Demotic was established as a standard administrative script throughout a re-unified Egypt.

Influence

[edit]Hieratic has had influence on a number of other writing systems. The most obvious is that on Demotic, its direct descendant. Related to this are the Demotic signs of the Meroitic script and the borrowed Demotic characters used in the Coptic alphabet and Old Nubian.

Outside of the Nile Valley, many of the signs used in the Byblos syllabary apparently were borrowed from Old Kingdom hieratic signs.[14] It is also known that early Hebrew used hieratic numerals.[15][16]

Unicode

[edit]The Unicode standard considers hieratic characters to be font variants of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the two scripts have been unified.[17] Hieroglyphs were added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b McGregor 2015, p. 306.

- ^ Goedicke (1988, p. vii); Wente (2001, p. 2006). The reference is made in Clement's Stromata 5:4.

- ^ Definition of hieratic, Free Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ Friedhelm Hoffmann (2012), Hieratic And Demotic Literature, OUP.

- ^ Baines 1983, p. 583.

- ^ Soukiassian, Wuttmann & Pantalacci 2002.

- ^ Posener-Kriéger 1992.

- ^ Pantalacci 1998.

- ^ Scribes and craftsmen: the noble art of writing on clay. Archived 2016-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Feb 29, 2012; UCL Institute of Archaeology

- ^ Parkinson & Quirke 1995, p. 20.

- ^ Gardiner 1929.

- ^ Wente 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Malinine 1974.

- ^ Hoch 1990.

- ^ Aharoni 1966.

- ^ Goldwasser 1991.

- ^ The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2.0, Chapter 14.17, Egyptian Hieroglyphs [1]

Bibliography

[edit]- Aharoni, Yohanan (1966). "The Use of Hieratic Numerals in Hebrew Ostraca and the Shekel Weights". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 184 (184): 13–19. doi:10.2307/1356200. JSTOR 1356200. S2CID 163341078.

- Baines, John R. (1983). "Literacy and Ancient Egyptian Society". Man: A Monthly Record of Anthropological Science. 18 (new series): 572–599. Archived from the original on 2006-10-09.

- Betrò, Maria Carmela (1996). Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt. New York; Milan: Abbeville Press (English); Arnoldo Mondadori (Italian). pp. 34–239. ISBN 978-0-7892-0232-1.

- Fischer-Elfert, Hans-Werner (2021). Grundzüge einer Geschichte des Hieratischen. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie. Vol. 14. Berlin: Lit.

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1929). "The Transcription of New Kingdom Hieratic". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 15 (1/2): 48–55. doi:10.2307/3854012. JSTOR 3854012.

- Goedicke, Hans (1988). Old Hieratic Paleography. Baltimore: Halgo, Inc.

- Goldwasser, Orly (1991). "An Egyptian Scribe from Lachish and the Hieratic Tradition of the Hebrew Kingdoms". Tel Aviv: Journal of the Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology. 18: 248–253.

- Hoch, James E. (1990). "The Byblos Syllabary: Bridging the Gap Between Egyptian Hieroglyphs and Semitic Alphabets". Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities. 20: 115–124.

- Janssen, Jacobus Johannes (2000). "Idiosyncrasies in Late Ramesside Hieratic Writing". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 86: 51–56. doi:10.2307/3822306. JSTOR 3822306.

- Malinine, Michel (1974). "Choix de textes juridiques en hiératique 'anormal' et en démotique". Textes et langages de l'Égypte pharaonique: Cent cinquante années de recherches 1822–1972; Hommage à Jean-François Champollion. Vol. 1. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire. pp. 31–35.

- McGregor, William B. (2015). Linguistics: An Introduction. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-567-48339-3.

- Möller, Georg Christian Julius (1927–1936). Hieratische Paläographie: Die aegyptische Buchschrift in ihrer Entwicklung von der Fünften Dynastie bis zur römischen Kaiserzeit (2nd ed.). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs’schen Buchhandlungen. 4 vols.

- Möller, Georg Christian Julius (1927–1935). Hieratische Lesestücke für den akademischen Gebrauch (2nd ed.). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs’schen Buchhandlungen. 3 vols.

- Pantalacci, Laure (1998). "La documentation épistolaire du palais des gouverneurs à Balat–ˤAyn Asīl". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. 98: 303–315.

- Parkinson, Richard B.; Quirke, Stephen G. J. (1995). Papyrus. London: British Museum Press.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule (1992). "Les tablettes en terre crue de Balat". In Élisabeth Lalou (ed.). Les Tablettes à écrire de l'Antiquité à l'époque moderne. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 41–49.

- Soukiassian, Georges; Wuttmann, Michel; Pantalacci, Laure (2002). Le palais des gouverneurs de l'époque de Pépy II: Les sanctuaires de ka et leurs dépendances. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire. ISBN 978-2-7247-0313-9.

- Verhoeven, Ursula (2001). Untersuchungen zur späthieratischen Buchschrift. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters and Departement Oriëntalistiek.

- Wente, Edward Frank (2001). "Scripts: Hieratic". In Donald Redford (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 206–210.

- Wimmer, Stefan Jakob (1989). Hieratische Paläographie der nicht-literarischen Ostraka der 19. und 20. Dynastie. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

External links

[edit]- Ancient Egyptian scripts – hieratic

- The Hieratic Script

- Egyptian scripts at the Wayback Machine (archived 2016-11-21)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch