Knowledge

| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

Knowledge is an awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often characterized as true belief that is distinct from opinion or guesswork by virtue of justification. While there is wide agreement among philosophers that propositional knowledge is a form of true belief, many controversies focus on justification. This includes questions like how to understand justification, whether it is needed at all, and whether something else besides it is needed. These controversies intensified in the latter half of the 20th century due to a series of thought experiments called Gettier cases that provoked alternative definitions.

Knowledge can be produced in many ways. The main source of empirical knowledge is perception, which involves the usage of the senses to learn about the external world. Introspection allows people to learn about their internal mental states and processes. Other sources of knowledge include memory, rational intuition, inference, and testimony.[a] According to foundationalism, some of these sources are basic in that they can justify beliefs, without depending on other mental states. Coherentists reject this claim and contend that a sufficient degree of coherence among all the mental states of the believer is necessary for knowledge. According to infinitism, an infinite chain of beliefs is needed.

The main discipline investigating knowledge is epistemology, which studies what people know, how they come to know it, and what it means to know something. It discusses the value of knowledge and the thesis of philosophical skepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge. Knowledge is relevant to many fields like the sciences, which aim to acquire knowledge using the scientific method based on repeatable experimentation, observation, and measurement. Various religions hold that humans should seek knowledge and that God or the divine is the source of knowledge. The anthropology of knowledge studies how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated in different cultures. The sociology of knowledge examines under what sociohistorical circumstances knowledge arises, and what sociological consequences it has. The history of knowledge investigates how knowledge in different fields has developed, and evolved, in the course of history.

Definitions

Knowledge is a form of familiarity, awareness, understanding, or acquaintance. It often involves the possession of information learned through experience[1] and can be understood as a cognitive success or an epistemic contact with reality, like making a discovery.[2] Many academic definitions focus on propositional knowledge in the form of believing certain facts, as in "I know that Dave is at home".[3] Other types of knowledge include knowledge-how in the form of practical competence, as in "she knows how to swim", and knowledge by acquaintance as a familiarity with the known object based on previous direct experience, like knowing someone personally.[4]

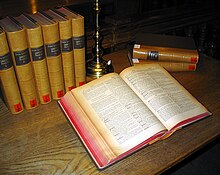

Knowledge is often understood as a state of an individual person, but it can also refer to a characteristic of a group of people as group knowledge, social knowledge, or collective knowledge.[5] Some social sciences understand knowledge as a broad social phenomenon that is similar to culture.[6] The term may further denote knowledge stored in documents like the "knowledge housed in the library"[7] or the knowledge base of an expert system.[8] Knowledge is closely related to intelligence, but intelligence is more about the ability to acquire, process, and apply information, while knowledge concerns information and skills that a person already possesses.[9]

The word knowledge has its roots in the 12th-century Old English word cnawan, which comes from the Old High German word gecnawan.[10] The English word includes various meanings that some other languages distinguish using several words.[11] In ancient Greek, for example, four important terms for knowledge were used: epistēmē (unchanging theoretical knowledge), technē (expert technical knowledge), mētis (strategic knowledge), and gnōsis (personal intellectual knowledge).[12] The main discipline studying knowledge is called epistemology or the theory of knowledge. It examines the nature of knowledge and justification, how knowledge arises, and what value it has. Further topics include the different types of knowledge and the limits of what can be known.[13]

Despite agreements about the general characteristics of knowledge, its exact definition is disputed. Some definitions only focus on the most salient features of knowledge to give a practically useful characterization.[14] Another approach, termed analysis of knowledge, tries to provide a theoretically precise definition by listing the conditions that are individually necessary and jointly sufficient,[15] similar to how chemists analyze a sample by seeking a list of all the chemical elements composing it.[16] According to a different view, knowledge is a unique state that cannot be analyzed in terms of other phenomena.[17] Some scholars base their definition on abstract intuitions while others focus on concrete cases[18] or rely on how the term is used in ordinary language.[19] There is also disagreement about whether knowledge is a rare phenomenon that requires high standards or a common phenomenon found in many everyday situations.[20]

Analysis of knowledge

An often-discussed definition characterizes knowledge as justified true belief. This definition identifies three essential features: it is (1) a belief that is (2) true and (3) justified.[21][b] Truth is a widely accepted feature of knowledge. It implies that, while it may be possible to believe something false, one cannot know something false.[23][c] That knowledge is a form of belief implies that one cannot know something if one does not believe it. Some everyday expressions seem to violate this principle, like the claim that "I do not believe it, I know it!" But the point of such expressions is usually to emphasize one's confidence rather than denying that a belief is involved.[25]

The main controversy surrounding this definition concerns its third feature: justification.[26] This component is often included because of the impression that some true beliefs are not forms of knowledge, such as beliefs based on superstition, lucky guesses, or erroneous reasoning. For example, a person who guesses that a coin flip will land heads usually does not know that even if their belief turns out to be true. This indicates that there is more to knowledge than just being right about something.[27] These cases are excluded by requiring that beliefs have justification for them to count as knowledge.[28] Some philosophers hold that a belief is justified if it is based on evidence, which can take the form of mental states like experience, memory, and other beliefs. Others state that beliefs are justified if they are produced by reliable processes, like sensory perception or logical reasoning.[29]

The definition of knowledge as justified true belief came under severe criticism in the 20th century, when epistemologist Edmund Gettier formulated a series of counterexamples.[30] They purport to present concrete cases of justified true beliefs that fail to constitute knowledge. The reason for their failure is usually a form of epistemic luck: the beliefs are justified but their justification is not relevant to the truth.[31] In a well-known example, someone drives along a country road with many barn facades and only one real barn. The person is not aware of this, stops in front of the real barn by a lucky coincidence, and forms the justified true belief that they are in front of a barn. This example aims to establish that the person does not know that they are in front of a real barn, since they would not have been able to tell the difference.[32] This means that it is a lucky coincidence that this justified belief is also true.[33]

According to some philosophers, these counterexamples show that justification is not required for knowledge[34] and that knowledge should instead be characterized in terms of reliability or the manifestation of cognitive virtues. Another approach defines knowledge in regard to the function it plays in cognitive processes as that which provides reasons for thinking or doing something.[35] A different response accepts justification as an aspect of knowledge and include additional criteria.[36] Many candidates have been suggested, like the requirements that the justified true belief does not depend on any false beliefs, that no defeaters[d] are present, or that the person would not have the belief if it was false.[38] Another view states that beliefs have to be infallible to amount to knowledge.[39] A further approach, associated with pragmatism, focuses on the aspect of inquiry and characterizes knowledge in terms of what works as a practice that aims to produce habits of action.[40] There is still very little consensus in the academic discourse as to which of the proposed modifications or reconceptualizations is correct, and there are various alternative definitions of knowledge.[41]

Types

A common distinction among types of knowledge is between propositional knowledge, or knowledge-that, and non-propositional knowledge in the form of practical skills or acquaintance.[42][e] Other distinctions focus on how the knowledge is acquired and on the content of the known information.[44]

Propositional

Propositional knowledge, also referred to as declarative and descriptive knowledge, is a form of theoretical knowledge about facts, like knowing that "2 + 2 = 4". It is the paradigmatic type of knowledge in analytic philosophy.[45] Propositional knowledge is propositional in the sense that it involves a relation to a proposition. Since propositions are often expressed through that-clauses, it is also referred to as knowledge-that, as in "Akari knows that kangaroos hop".[46] In this case, Akari stands in the relation of knowing to the proposition "kangaroos hop". Closely related types of knowledge are know-wh, for example, knowing who is coming to dinner and knowing why they are coming.[47] These expressions are normally understood as types of propositional knowledge since they can be paraphrased using a that-clause.[48][f]

Propositional knowledge takes the form of mental representations involving concepts, ideas, theories, and general rules. These representations connect the knower to certain parts of reality by showing what they are like. They are often context-independent, meaning that they are not restricted to a specific use or purpose.[50] Propositional knowledge encompasses both knowledge of specific facts, like that the atomic mass of gold is 196.97 u, and generalities, like that the color of leaves of some trees changes in autumn.[51] Because of the dependence on mental representations, it is often held that the capacity for propositional knowledge is exclusive to relatively sophisticated creatures, such as humans. This is based on the claim that advanced intellectual capacities are needed to believe a proposition that expresses what the world is like.[52]

Non-propositional

Non-propositional knowledge is knowledge in which no essential relation to a proposition is involved. The two most well-known forms are knowledge-how (know-how or procedural knowledge) and knowledge by acquaintance.[53] To possess knowledge-how means to have some form of practical ability, skill, or competence,[54] like knowing how to ride a bicycle or knowing how to swim. Some of the abilities responsible for knowledge-how involve forms of knowledge-that, as in knowing how to prove a mathematical theorem, but this is not generally the case.[55] Some types of knowledge-how do not require a highly developed mind, in contrast to propositional knowledge, and are more common in the animal kingdom. For example, an ant knows how to walk even though it presumably lacks a mind sufficiently developed to represent the corresponding proposition.[52][g]

Knowledge by acquaintance is familiarity with something that results from direct experiential contact.[57] The object of knowledge can be a person, a thing, or a place. For example, by eating chocolate, one becomes acquainted with the taste of chocolate, and visiting Lake Taupō leads to the formation of knowledge by acquaintance of Lake Taupō. In these cases, the person forms non-inferential knowledge based on first-hand experience without necessarily acquiring factual information about the object. By contrast, it is also possible to indirectly learn a lot of propositional knowledge about chocolate or Lake Taupō by reading books without having the direct experiential contact required for knowledge by acquaintance.[58] The concept of knowledge by acquaintance was first introduced by Bertrand Russell. He holds that knowledge by acquaintance is more basic than propositional knowledge since to understand a proposition, one has to be acquainted with its constituents.[59]

A priori and a posteriori

The distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge depends on the role of experience in the processes of formation and justification.[60] To know something a posteriori means to know it based on experience.[61] For example, by seeing that it rains outside or hearing that the baby is crying, one acquires a posteriori knowledge of these facts.[62] A priori knowledge is possible without any experience to justify or support the known proposition.[63] Mathematical knowledge, such as that 2 + 2 = 4, is traditionally taken to be a priori knowledge since no empirical investigation is necessary to confirm this fact. In this regard, a posteriori knowledge is empirical knowledge while a priori knowledge is non-empirical knowledge.[64]

The relevant experience in question is primarily identified with sensory experience. Some non-sensory experiences, like memory and introspection, are often included as well. Some conscious phenomena are excluded from the relevant experience, like rational insight. For example, conscious thought processes may be required to arrive at a priori knowledge regarding the solution of mathematical problems, like when performing mental arithmetic to multiply two numbers.[65] The same is the case for the experience needed to learn the words through which the claim is expressed. For example, knowing that "all bachelors are unmarried" is a priori knowledge because no sensory experience is necessary to confirm this fact even though experience was needed to learn the meanings of the words "bachelor" and "unmarried".[66]

It is difficult to explain how a priori knowledge is possible and some empiricists deny it exists. It is usually seen as unproblematic that one can come to know things through experience, but it is not clear how knowledge is possible without experience. One of the earliest solutions to this problem comes from Plato, who argues that the soul already possesses the knowledge and just needs to recollect, or remember, it to access it again.[67] A similar explanation is given by Descartes, who holds that a priori knowledge exists as innate knowledge present in the mind of each human.[68] A further approach posits a special mental faculty responsible for this type of knowledge, often referred to as rational intuition or rational insight.[69]

Others

Various other types of knowledge are discussed in the academic literature. In philosophy, "self-knowledge" refers to a person's knowledge of their own sensations, thoughts, beliefs, and other mental states. A common view is that self-knowledge is more direct than knowledge of the external world, which relies on the interpretation of sense data. Because of this, it is traditionally claimed that self-knowledge is indubitable, like the claim that a person cannot be wrong about whether they are in pain. However, this position is not universally accepted in the contemporary discourse and an alternative view states that self-knowledge also depends on interpretations that could be false.[70] In a slightly different sense, self-knowledge can also refer to knowledge of the self as a persisting entity with certain personality traits, preferences, physical attributes, relationships, goals, and social identities.[71][h]

Metaknowledge is knowledge about knowledge. It can arise in the form of self-knowledge but includes other types as well, such as knowing what someone else knows or what information is contained in a scientific article. Other aspects of metaknowledge include knowing how knowledge can be acquired, stored, distributed, and used.[73]

Common knowledge is knowledge that is publicly known and shared by most individuals within a community. It establishes a common ground for communication, understanding, social cohesion, and cooperation.[74] General knowledge encompasses common knowledge but also includes knowledge that many people have been exposed to but may not be able to immediately recall.[75] Common knowledge contrasts with domain knowledge or specialized knowledge, which belongs to a specific domain and is only possessed by experts.[76]

Situated knowledge is knowledge specific to a particular situation.[77] It is closely related to practical or tacit knowledge, which is learned and applied in specific circumstances. This especially concerns certain forms of acquiring knowledge, such as trial and error or learning from experience.[78] In this regard, situated knowledge usually lacks a more explicit structure and is not articulated in terms of universal ideas.[79] The term is often used in feminism and postmodernism to argue that many forms of knowledge are not absolute but depend on the concrete historical, cultural, and linguistic context.[77]

Explicit knowledge is knowledge that can be fully articulated, shared, and explained, like the knowledge of historical dates and mathematical formulas. It can be acquired through traditional learning methods, such as reading books and attending lectures. It contrasts with tacit knowledge, which is not easily articulated or explained to others, like the ability to recognize someone's face and the practical expertise of a master craftsman. Tacit knowledge is often learned through first-hand experience or direct practice.[80]

Cognitive load theory distinguishes between biologically primary and secondary knowledge. Biologically primary knowledge is knowledge that humans have as part of their evolutionary heritage, such as knowing how to recognize faces and speech and many general problem-solving capacities. Biologically secondary knowledge is knowledge acquired because of specific social and cultural circumstances, such as knowing how to read and write.[81]

Knowledge can be occurrent or dispositional. Occurrent knowledge is knowledge that is actively involved in cognitive processes. Dispositional knowledge, by contrast, lies dormant in the back of a person's mind and is given by the mere ability to access the relevant information. For example, if a person knows that cats have whiskers then this knowledge is dispositional most of the time and becomes occurrent while they are thinking about it.[82]

Many forms of Eastern spirituality and religion distinguish between higher and lower knowledge. They are also referred to as para vidya and apara vidya in Hinduism or the two truths doctrine in Buddhism. Lower knowledge is based on the senses and the intellect. It encompasses both mundane or conventional truths as well as discoveries of the empirical sciences.[83] Higher knowledge is understood as knowledge of God, the absolute, the true self, or the ultimate reality. It belongs neither to the external world of physical objects nor to the internal world of the experience of emotions and concepts. Many spiritual teachings stress the importance of higher knowledge to progress on the spiritual path and to see reality as it truly is beyond the veil of appearances.[84]

Sources

Sources of knowledge are ways in which people come to know things. They can be understood as cognitive capacities that are exercised when a person acquires new knowledge.[85] Various sources of knowledge are discussed in the academic literature, often in terms of the mental faculties responsible. They include perception, introspection, memory, inference, and testimony. However, not everyone agrees that all of them actually lead to knowledge. Usually, perception or observation, i.e. using one of the senses, is identified as the most important source of empirical knowledge.[86] Knowing that a baby is sleeping is observational knowledge if it was caused by a perception of the snoring baby. However, this would not be the case if one learned about this fact through a telephone conversation with one's spouse. Perception comes in different modalities, including vision, sound, touch, smell, and taste, which correspond to different physical stimuli.[87] It is an active process in which sensory signals are selected, organized, and interpreted to form a representation of the environment. This leads in some cases to illusions that misrepresent certain aspects of reality, like the Müller-Lyer illusion and the Ponzo illusion.[88]

Introspection is often seen in analogy to perception as a source of knowledge, not of external physical objects, but of internal mental states. A traditionally common view is that introspection has a special epistemic status by being infallible. According to this position, it is not possible to be mistaken about introspective facts, like whether one is in pain, because there is no difference between appearance and reality. However, this claim has been contested in the contemporary discourse and critics argue that it may be possible, for example, to mistake an unpleasant itch for a pain or to confuse the experience of a slight ellipse for the experience of a circle.[89] Perceptual and introspective knowledge often act as a form of fundamental or basic knowledge. According to some empiricists, they are the only sources of basic knowledge and provide the foundation for all other knowledge.[90]

Memory differs from perception and introspection in that it is not as independent or basic as they are since it depends on other previous experiences.[91] The faculty of memory retains knowledge acquired in the past and makes it accessible in the present, as when remembering a past event or a friend's phone number.[92] It is generally seen as a reliable source of knowledge. However, it can be deceptive at times nonetheless, either because the original experience was unreliable or because the memory degraded and does not accurately represent the original experience anymore.[93][i]

Knowledge based on perception, introspection, and memory may give rise to inferential knowledge, which comes about when reasoning is applied to draw inferences from other known facts.[95] For example, the perceptual knowledge of a Czech stamp on a postcard may give rise to the inferential knowledge that one's friend is visiting the Czech Republic. This type of knowledge depends on other sources of knowledge responsible for the premises. Some rationalists argue for rational intuition as a further source of knowledge that does not rely on observation and introspection. They hold for example that some beliefs, like the mathematical belief that 2 + 2 = 4, are justified through pure reason alone.[96]

Testimony is often included as an additional source of knowledge that, unlike the other sources, is not tied to one specific cognitive faculty. Instead, it is based on the idea that one person can come to know a fact because another person talks about this fact. Testimony can happen in numerous ways, like regular speech, a letter, a newspaper, or a blog. The problem of testimony consists in clarifying why and under what circumstances testimony can lead to knowledge. A common response is that it depends on the reliability of the person pronouncing the testimony: only testimony from reliable sources can lead to knowledge.[97]

Limits

The problem of the limits of knowledge concerns the question of which facts are unknowable.[98] These limits constitute a form of inevitable ignorance that can affect both what is knowable about the external world as well as what one can know about oneself and about what is good.[99] Some limits of knowledge only apply to particular people in specific situations while others pertain to humanity at large.[100] A fact is unknowable to a person if this person lacks access to the relevant information, like facts in the past that did not leave any significant traces. For example, it may be unknowable to people today what Caesar's breakfast was the day he was assassinated but it was knowable to him and some contemporaries.[101] Another factor restricting knowledge is given by the limitations of the human cognitive faculties. Some people may lack the cognitive ability to understand highly abstract mathematical truths and some facts cannot be known by any human because they are too complex for the human mind to conceive.[102] A further limit of knowledge arises due to certain logical paradoxes. For instance, there are some ideas that will never occur to anyone. It is not possible to know them because if a person knew about such an idea then this idea would have occurred at least to them.[103][j]

There are many disputes about what can or cannot be known in certain fields. Religious skepticism is the view that beliefs about God or other religious doctrines do not amount to knowledge.[105] Moral skepticism encompasses a variety of views, including the claim that moral knowledge is impossible, meaning that one cannot know what is morally good or whether a certain behavior is morally right.[106] An influential theory about the limits of metaphysical knowledge was proposed by Immanuel Kant. For him, knowledge is restricted to the field of appearances and does not reach the things in themselves, which exist independently of humans and lie beyond the realm of appearances. Based on the observation that metaphysics aims to characterize the things in themselves, he concludes that no metaphysical knowledge is possible, like knowing whether the world has a beginning or is infinite.[107]

There are also limits to knowledge in the empirical sciences, such as the uncertainty principle, which states that it is impossible to know the exact magnitudes of certain certain pairs of physical properties, like the position and momentum of a particle, at the same time.[108] Other examples are physical systems studied by chaos theory, for which it is not practically possible to predict how they will behave since they are so sensitive to initial conditions that even the slightest of variations may produce a completely different behavior. This phenomenon is known as the butterfly effect.[109]

The strongest position about the limits of knowledge is radical or global skepticism, which holds that humans lack any form of knowledge or that knowledge is impossible. For example, the dream argument states that perceptual experience is not a source of knowledge since dreaming provides unreliable information and a person could be dreaming without knowing it. Because of this inability to discriminate between dream and perception, it is argued that there is no perceptual knowledge of the external world.[110][k] This thought experiment is based on the problem of underdetermination, which arises when the available evidence is not sufficient to make a rational decision between competing theories. In such cases, a person is not justified in believing one theory rather than the other. If this is always the case then global skepticism follows.[111] Another skeptical argument assumes that knowledge requires absolute certainty and aims to show that all human cognition is fallible since it fails to meet this standard.[112]

An influential argument against radical skepticism states that radical skepticism is self-contradictory since denying the existence of knowledge is itself a knowledge-claim.[113] Other arguments rely on common sense[114] or deny that infallibility is required for knowledge.[115] Very few philosophers have explicitly defended radical skepticism but this position has been influential nonetheless, usually in a negative sense: many see it as a serious challenge to any epistemological theory and often try to show how their preferred theory overcomes it.[116] Another form of philosophical skepticism advocates the suspension of judgment as a form of attaining tranquility while remaining humble and open-minded.[117]

A less radical limit of knowledge is identified by fallibilists, who argue that the possibility of error can never be fully excluded. This means that even the best-researched scientific theories and the most fundamental common-sense views could still be subject to error. Further research may reduce the possibility of being wrong, but it can never fully exclude it. Some fallibilists reach the skeptical conclusion from this observation that there is no knowledge but the more common view is that knowledge exists but is fallible.[118] Pragmatists argue that one consequence of fallibilism is that inquiry should not aim for truth or absolute certainty but for well-supported and justified beliefs while remaining open to the possibility that one's beliefs may need to be revised later.[119]

Structure

The structure of knowledge is the way in which the mental states of a person need to be related to each other for knowledge to arise.[120] A common view is that a person has to have good reasons for holding a belief if this belief is to amount to knowledge. When the belief is challenged, the person may justify it by referring to their reason for holding it. In many cases, this reason depends itself on another belief that may as well be challenged. An example is a person who believes that Ford cars are cheaper than BMWs. When their belief is challenged, they may justify it by claiming that they heard it from a reliable source. This justification depends on the assumption that their source is reliable, which may itself be challenged. The same may apply to any subsequent reason they cite.[121] This threatens to lead to an infinite regress since the epistemic status at each step depends on the epistemic status of the previous step.[122] Theories of the structure of knowledge offer responses for how to solve this problem.[121]

Three traditional theories are foundationalism, coherentism, and infinitism. Foundationalists and coherentists deny the existence of an infinite regress, in contrast to infinitists.[121] According to foundationalists, some basic reasons have their epistemic status independent of other reasons and thereby constitute the endpoint of the regress.[123] Some foundationalists hold that certain sources of knowledge, like perception, provide basic reasons. Another view is that this role is played by certain self-evident truths, like the knowledge of one's own existence and the content of one's ideas.[124] The view that basic reasons exist is not universally accepted. One criticism states that there should be a reason why some reasons are basic while others are not. According to this view, the putative basic reasons are not actually basic since their status would depend on other reasons. Another criticism is based on hermeneutics and argues that all understanding is circular and requires interpretation, which implies that knowledge does not need a secure foundation.[125]

Coherentists and infinitists avoid these problems by denying the contrast between basic and non-basic reasons. Coherentists argue that there is only a finite number of reasons, which mutually support and justify one another. This is based on the intuition that beliefs do not exist in isolation but form a complex web of interconnected ideas that is justified by its coherence rather than by a few privileged foundational beliefs.[126] One difficulty for this view is how to demonstrate that it does not involve the fallacy of circular reasoning.[127] If two beliefs mutually support each other then a person has a reason for accepting one belief if they already have the other. However, mutual support alone is not a good reason for newly accepting both beliefs at once. A closely related issue is that there can be distinct sets of coherent beliefs. Coherentists face the problem of explaining why someone should accept one coherent set rather than another.[126] For infinitists, in contrast to foundationalists and coherentists, there is an infinite number of reasons. This view embraces the idea that there is a regress since each reason depends on another reason. One difficulty for this view is that the human mind is limited and may not be able to possess an infinite number of reasons. This raises the question of whether, according to infinitism, human knowledge is possible at all.[128]

Value

Knowledge may be valuable either because it is useful or because it is good in itself. Knowledge can be useful by helping a person achieve their goals. For example, if one knows the answers to questions in an exam one is able to pass that exam or by knowing which horse is the fastest, one can earn money from bets. In these cases, knowledge has instrumental value.[129] Not all forms of knowledge are useful and many beliefs about trivial matters have no instrumental value. This concerns, for example, knowing how many grains of sand are on a specific beach or memorizing phone numbers one never intends to call. In a few cases, knowledge may even have a negative value. For example, if a person's life depends on gathering the courage to jump over a ravine, then having a true belief about the involved dangers may hinder them from doing so.[130]

Besides having instrumental value, knowledge may also have intrinsic value. This means that some forms of knowledge are good in themselves even if they do not provide any practical benefits. According to philosopher Duncan Pritchard, this applies to forms of knowledge linked to wisdom.[131] It is controversial whether all knowledge has intrinsic value, including knowledge about trivial facts like knowing whether the biggest apple tree had an even number of leaves yesterday morning. One view in favor of the intrinsic value of knowledge states that having no belief about a matter is a neutral state and knowledge is always better than this neutral state, even if the value difference is only minimal.[132]

A more specific issue in epistemology concerns the question of whether or why knowledge is more valuable than mere true belief.[133] There is wide agreement that knowledge is usually good in some sense but the thesis that knowledge is better than true belief is controversial. An early discussion of this problem is found in Plato's Meno in relation to the claim that both knowledge and true belief can successfully guide action and, therefore, have apparently the same value. For example, it seems that mere true belief is as effective as knowledge when trying to find the way to Larissa.[134] According to Plato, knowledge is better because it is more stable.[135] Another suggestion is that knowledge gets its additional value from justification. One difficulty for this view is that while justification makes it more probable that a belief is true, it is not clear what additional value it provides in comparison to an unjustified belief that is already true.[136]

The problem of the value of knowledge is often discussed in relation to reliabilism and virtue epistemology.[137] Reliabilism can be defined as the thesis that knowledge is reliably formed true belief. This view has difficulties in explaining why knowledge is valuable or how a reliable belief-forming process adds additional value.[138] According to an analogy by philosopher Linda Zagzebski, a cup of coffee made by a reliable coffee machine has the same value as an equally good cup of coffee made by an unreliable coffee machine.[139] This difficulty in solving the value problem is sometimes used as an argument against reliabilism.[140] Virtue epistemology, by contrast, offers a unique solution to the value problem. Virtue epistemologists see knowledge as the manifestation of cognitive virtues. They hold that knowledge has additional value due to its association with virtue. This is based on the idea that cognitive success in the form of the manifestation of virtues is inherently valuable independent of whether the resulting states are instrumentally useful.[141]

Acquiring and transmitting knowledge often comes with certain costs, such as the material resources required to obtain new information and the time and energy needed to understand it. For this reason, an awareness of the value of knowledge is crucial to many fields that have to make decisions about whether to seek knowledge about a specific matter. On a political level, this concerns the problem of identifying the most promising research programs to allocate funds.[142] Similar concerns affect businesses, where stakeholders have to decide whether the cost of acquiring knowledge is justified by the economic benefits that this knowledge may provide, and the military, which relies on intelligence to identify and prevent threats.[143] In the field of education, the value of knowledge can be used to choose which knowledge should be passed on to the students.[144]

Science

The scientific approach is usually regarded as an exemplary process of how to gain knowledge about empirical facts.[145] Scientific knowledge includes mundane knowledge about easily observable facts, for example, chemical knowledge that certain reactants become hot when mixed together. It also encompasses knowledge of less tangible issues, like claims about the behavior of genes, neutrinos, and black holes.[146]

A key aspect of most forms of science is that they seek natural laws that explain empirical observations.[145] Scientific knowledge is discovered and tested using the scientific method.[l] This method aims to arrive at reliable knowledge by formulating the problem in a clear way and by ensuring that the evidence used to support or refute a specific theory is public, reliable, and replicable. This way, other researchers can repeat the experiments and observations in the initial study to confirm or disconfirm it.[148] The scientific method is often analyzed as a series of steps that begins with regular observation and data collection. Based on these insights, scientists then try to find a hypothesis that explains the observations. The hypothesis is then tested using a controlled experiment to compare whether predictions based on the hypothesis match the observed results. As a last step, the results are interpreted and a conclusion is reached whether and to what degree the findings confirm or disconfirm the hypothesis.[149]

The empirical sciences are usually divided into natural and social sciences. The natural sciences, like physics, biology, and chemistry, focus on quantitative research methods to arrive at knowledge about natural phenomena.[150] Quantitative research happens by making precise numerical measurements and the natural sciences often rely on advanced technological instruments to perform these measurements and to setup experiments. Another common feature of their approach is to use mathematical tools to analyze the measured data and formulate exact and general laws to describe the observed phenomena.[151]

The social sciences, like sociology, anthropology, and communication studies, examine social phenomena on the level of human behavior, relationships, and society at large.[152] While they also make use of quantitative research, they usually give more emphasis to qualitative methods. Qualitative research gathers non-numerical data, often with the goal of arriving at a deeper understanding of the meaning and interpretation of social phenomena from the perspective of those involved.[153] This approach can take various forms, such as interviews, focus groups, and case studies.[154] Mixed-method research combines quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the same phenomena from a variety of perspectives to get a more comprehensive understanding.[155]

The progress of scientific knowledge is traditionally seen as a gradual and continuous process in which the existing body of knowledge is increased at each step. This view has been challenged by some philosophers of science, such as Thomas Kuhn, who holds that between phases of incremental progress, there are so-called scientific revolutions in which a paradigm shift occurs. According to this view, some basic assumptions are changed due to the paradigm shift, resulting in a radically new perspective on the body of scientific knowledge that is incommensurable with the previous outlook.[156][m]

Scientism refers to a group of views that privilege the sciences and the scientific method over other forms of inquiry and knowledge acquisition. In its strongest formulation, it is the claim that there is no other knowledge besides scientific knowledge.[158] A common critique of scientism, made by philosophers such as Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Feyerabend, is that the fixed requirement of following the scientific method is too rigid and results in a misleading picture of reality by excluding various relevant phenomena from the scope of knowledge.[159]

History

The history of knowledge is the field of inquiry that studies how knowledge in different fields has developed and evolved in the course of history. It is closely related to the history of science, but covers a wider area that includes knowledge from fields like philosophy, mathematics, education, literature, art, and religion. It further covers practical knowledge of specific crafts, medicine, and everyday practices. It investigates not only how knowledge is created and employed, but also how it is disseminated and preserved.[160]

Before the ancient period, knowledge about social conduct and survival skills was passed down orally and in the form of customs from one generation to the next.[161] The ancient period saw the rise of major civilizations starting about 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China. The invention of writing in this period significantly increased the amount of stable knowledge within society since it could be stored and shared without being limited by imperfect human memory.[162] During this time, the first developments in scientific fields like mathematics, astronomy, and medicine were made. They were later formalized and greatly expanded by the ancient Greeks starting in the 6th century BCE. Other ancient advancements concerned knowledge in the fields of agriculture, law, and politics.[163]

In the medieval period, religious knowledge was a central concern, and religious institutions, like the Catholic Church in Europe, influenced intellectual activity.[164] Jewish communities set up yeshivas as centers for studying religious texts and Jewish law.[165] In the Muslim world, madrasa schools were established and focused on Islamic law and Islamic philosophy.[166] Many intellectual achievements of the ancient period were preserved, refined, and expanded during the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th to 13th centuries.[167] Centers of higher learning were established in this period in various regions, like Al-Qarawiyyin University in Morocco,[168] the Al-Azhar University in Egypt,[169] the House of Wisdom in Iraq,[170] and the first universities in Europe.[171] This period also saw the formation of guilds, which preserved and advanced technical and craft knowledge.[172]

In the Renaissance period, starting in the 14th century, there was a renewed interest in the humanities and sciences.[173] The printing press was invented in the 15th century and significantly increased the availability of written media and general literacy of the population.[174] These developments served as the foundation of the Scientific Revolution in the Age of Enlightenment starting in the 16th and 17th centuries. It led to an explosion of knowledge in fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, and the social sciences.[175] The technological advancements that accompanied this development made possible the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries.[176] In the 20th century, the development of computers and the Internet led to a vast expansion of knowledge by revolutionizing how knowledge is stored, shared, and created.[177][n]

In various disciplines

Religion

Knowledge plays a central role in many religions. Knowledge claims about the existence of God or religious doctrines about how each one should live their lives are found in almost every culture.[179] However, such knowledge claims are often controversial and are commonly rejected by religious skeptics and atheists.[180] The epistemology of religion is the field of inquiry studying whether belief in God and in other religious doctrines is rational and amounts to knowledge.[181] One important view in this field is evidentialism, which states that belief in religious doctrines is justified if it is supported by sufficient evidence. Suggested examples of evidence for religious doctrines include religious experiences such as direct contact with the divine or inner testimony when hearing God's voice.[182] Evidentialists often reject that belief in religious doctrines amounts to knowledge based on the claim that there is not sufficient evidence.[183] A famous saying in this regard is due to Bertrand Russell. When asked how he would justify his lack of belief in God when facing his judgment after death, he replied "Not enough evidence, God! Not enough evidence."[184]

However, religious teachings about the existence and nature of God are not always seen as knowledge claims by their defenders. Some explicitly state that the proper attitude towards such doctrines is not knowledge but faith. This is often combined with the assumption that these doctrines are true but cannot be fully understood by reason or verified through rational inquiry. For this reason, it is claimed that one should accept them even though they do not amount to knowledge.[180] Such a view is reflected in a famous saying by Immanuel Kant where he claims that he "had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith."[185]

Distinct religions often differ from each other concerning the doctrines they proclaim as well as their understanding of the role of knowledge in religious practice.[186] In both the Jewish and the Christian traditions, knowledge plays a role in the fall of man, in which Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden. Responsible for this fall was that they ignored God's command and ate from the tree of knowledge, which gave them the knowledge of good and evil. This is seen as a rebellion against God since this knowledge belongs to God and it is not for humans to decide what is right or wrong.[187] In the Christian literature, knowledge is seen as one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit.[188] In Islam, "the Knowing" (al-ʿAlīm) is one of the 99 names reflecting distinct attributes of God. The Qur'an asserts that knowledge comes from Allah and the acquisition of knowledge is encouraged in the teachings of Muhammad.[189]

In Buddhism, knowledge that leads to liberation is called vijjā. It contrasts with avijjā or ignorance, which is understood as the root of all suffering. This is often explained in relation to the claim that humans suffer because they crave things that are impermanent. The ignorance of the impermanent nature of things is seen as the factor responsible for this craving.[190] The central goal of Buddhist practice is to stop suffering. This aim is to be achieved by understanding and practicing the teaching known as the Four Noble Truths and thereby overcoming ignorance.[191] Knowledge plays a key role in the classical path of Hinduism known as jñāna yoga or "path of knowledge". It aims to achieve oneness with the divine by fostering an understanding of the self and its relation to Brahman or ultimate reality.[192]

Anthropology

The anthropology of knowledge is a multi-disciplinary field of inquiry.[193] It studies how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated.[194] Special interest is given to how knowledge is reproduced and changes in relation to social and cultural circumstances.[195] In this context, the term knowledge is used in a very broad sense, roughly equivalent to terms like understanding and culture.[196] This means that the forms and reproduction of understanding are studied irrespective of their truth value. In epistemology, by contrast, knowledge is usually restricted to forms of true belief. The main focus in anthropology is on empirical observations of how people ascribe truth values to meaning contents, like when affirming an assertion, even if these contents are false.[195] This also includes practical components: knowledge is what is employed when interpreting and acting on the world and involves diverse phenomena, such as feelings, embodied skills, information, and concepts. It is used to understand and anticipate events to prepare and react accordingly.[197]

The reproduction of knowledge and its changes often happen through some form of communication used to transfer knowledge.[198] This includes face-to-face discussions and online communications as well as seminars and rituals. An important role in this context falls to institutions, like university departments or scientific journals in the academic context.[195] Anthropologists of knowledge understand traditions as knowledge that has been reproduced within a society or geographic region over several generations. They are interested in how this reproduction is affected by external influences. For example, societies tend to interpret knowledge claims found in other societies and incorporate them in a modified form.[199]

Within a society, people belonging to the same social group usually understand things and organize knowledge in similar ways to one another. In this regard, social identities play a significant role: people who associate themselves with similar identities, like age-influenced, professional, religious, and ethnic identities, tend to embody similar forms of knowledge. Such identities concern both how a person sees themselves, for example, in terms of the ideals they pursue, as well as how other people see them, such as the expectations they have toward the person.[200]

Sociology

The sociology of knowledge is the subfield of sociology that studies how thought and society are related to each other.[201] Like the anthropology of knowledge, it understands "knowledge" in a wide sense that encompasses philosophical and political ideas, religious and ideological doctrines, folklore, law, and technology. The sociology of knowledge studies in what sociohistorical circumstances knowledge arises, what consequences it has, and on what existential conditions it depends. The examined conditions include physical, demographic, economic, and sociocultural factors. For instance, philosopher Karl Marx claimed that the dominant ideology in a society is a product of and changes with the underlying socioeconomic conditions.[201] Another example is found in forms of decolonial scholarship that claim that colonial powers are responsible for the hegemony of Western knowledge systems. They seek a decolonization of knowledge to undermine this hegemony.[202] A related issue concerns the link between knowledge and power, in particular, the extent to which knowledge is power. The philosopher Michel Foucault explored this issue and examined how knowledge and the institutions responsible for it control people through what he termed biopower by shaping societal norms, values, and regulatory mechanisms in fields like psychiatry, medicine, and the penal system.[203]

A central subfield is the sociology of scientific knowledge, which investigates the social factors involved in the production and validation of scientific knowledge. This encompasses examining the impact of the distribution of resources and rewards on the scientific process, which leads some areas of research to flourish while others languish. Further topics focus on selection processes, such as how academic journals decide whether to publish an article and how academic institutions recruit researchers, and the general values and norms characteristic of the scientific profession.[204]

Others

Formal epistemology studies knowledge using formal tools found in mathematics and logic.[205] An important issue in this field concerns the epistemic principles of knowledge. These are rules governing how knowledge and related states behave and in what relations they stand to each other. The transparency principle, also referred to as the luminosity of knowledge, states that it is impossible for someone to know something without knowing that they know it.[o][206] According to the conjunction principle, if a person has justified beliefs in two separate propositions, then they are also justified in believing the conjunction of these two propositions. In this regard, if Bob has a justified belief that dogs are animals and another justified belief that cats are animals, then he is justified to believe the conjunction that both dogs and cats are animals. Other commonly discussed principles are the closure principle and the evidence transfer principle.[207]

Knowledge management is the process of creating, gathering, storing, and sharing knowledge. It involves the management of information assets that can take the form of documents, databases, policies, and procedures. It is of particular interest in the field of business and organizational development, as it directly impacts decision-making and strategic planning. Knowledge management efforts are often employed to increase operational efficiency in attempts to gain a competitive advantage.[208] Key processes in the field of knowledge management are knowledge creation, knowledge storage, knowledge sharing, and knowledge application. Knowledge creation is the first step and involves the production of new information. Knowledge storage can happen through media like books, audio recordings, film, and digital databases. Secure storage facilitates knowledge sharing, which involves the transmission of information from one person to another. For the knowledge to be beneficial, it has to be put into practice, meaning that its insights should be used to either improve existing practices or implement new ones.[209]

Knowledge representation is the process of storing organized information, which may happen using various forms of media and also includes information stored in the mind.[210] It plays a key role in the artificial intelligence, where the term is used for the field of inquiry that studies how computer systems can efficiently represent information. This field investigates how different data structures and interpretative procedures can be combined to achieve this goal and which formal languages can be used to express knowledge items. Some efforts in this field are directed at developing general languages and systems that can be employed in a great variety of domains while others focus on an optimized representation method within one specific domain. Knowledge representation is closely linked to automatic reasoning because the purpose of knowledge representation formalisms is usually to construct a knowledge base from which inferences are drawn.[211] Influential knowledge base formalisms include logic-based systems, rule-based systems, semantic networks, and frames. Logic-based systems rely on formal languages employed in logic to represent knowledge. They use linguistic devices like individual terms, predicates, and quantifiers. For rule-based systems, each unit of information is expressed using a conditional production rule of the form "if A then B". Semantic nets model knowledge as a graph consisting of vertices to represent facts or concepts and edges to represent the relations between them. Frames provide complex taxonomies to group items into classes, subclasses, and instances.[212]

Pedagogy is the study of teaching methods or the art of teaching.[p] It explores how learning takes place and which techniques teachers may employ to transmit knowledge to students and improve their learning experience while keeping them motivated.[214] There is a great variety of teaching methods and the most effective approach often depends on factors like the subject matter and the age and proficiency level of the learner.[215] In teacher-centered education, the teacher acts as the authority figure imparting information and directing the learning process. Student-centered approaches give a more active role to students with the teacher acting as a coach to facilitate the process.[216] Further methodological considerations encompass the difference between group work and individual learning and the use of instructional media and other forms of educational technology.[217]

See also

- Epistemic modal logic – Type of modal logic

- Ignorance – Lack of knowledge and understanding

- Knowledge falsification – Deliberate misrepresentation of knowledge

- Omniscience – Capacity to know everything

- Outline of knowledge – Knowledge: what is known, understood, proven; information and products of learning

References

Notes

- ^ In this context, testimony is what other people report, both in spoken and written form.

- ^ A similar approach was already discussed in Ancient Greek philosophy in Plato's dialogue Theaetetus, where Socrates pondered the distinction between knowledge and true belief but rejected this definition.[22]

- ^ Truth is usually associated with objectivity. This view is rejected by relativism about truth, which argues that what is true depends on one's perspective.[24]

- ^ A defeater of a belief is evidence that this belief is false.[37]

- ^ A distinction similar to the one between knowledge-that and knowledge-how was already discussed in ancient Greece as the contrast between epistēmē (unchanging theoretical knowledge) and technē (expert technical knowledge).[43]

- ^ For instance, to know whether Ben is rich can be understood as knowing that Ben is rich, in case he is, and knowing that Ben is not rich, in case he is not.[49]

- ^ However, it is controversial to what extent goal-directed behavior in lower animals is comparable to human knowledge-how.[56]

- ^ Individuals may lack a deeper understanding of their character and feelings and attaining self-knowledge is one step in psychoanalysis.[72]

- ^ Confabulation is a special type of memory error that consists remembering events that did not happen, often provoked by an attempt to fill memory gaps.[94]

- ^ An often-cited paradox from the field of formal epistemology is Fitch's paradox of knowability, which states that knowledge has limits because denying this claim leads to the absurd conclusion that every truth is known.[104]

- ^ A similar often-cited thought experiment assumes that a person is not a regular human being but a brain in a vat that receives electrical stimuli. These stimuli give the brain the false impression of having a body and interacting with the external world. Since the person is unable to tell the difference, it is argued that they do not know that they have a body responsible for reliable perceptions.[111]

- ^ It is controversial to what extent there is a single scientific method that applies equally to all sciences rather than a group of related approaches.[147]

- ^ It is controversial how radical the difference between paradigms is and whether they truly are incommensurable.[157]

- ^ The internet also reduced the cost of accessing knowledge with a lot of information being freely available.[178]

- ^ This principle implies that if Heike knows that today is Monday, then she also knows that she knows that today is Monday.

- ^ The exact definition of the term is disputed.[213]

Citations

- ^

- ^

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 109

- Steup & Neta 2020, Lead Section, § 1. The Varieties of Cognitive Success

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.1 The Truth Condition, § 1.2 The Belief Condition

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Stanley & Willlamson 2001, pp. 411–412

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ^

- Klausen 2015, pp. 813–818

- Lackey 2021, pp. 111–112

- ^

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72

- Allen 2005, § Sociology of Knowledge

- Barth 2002, p. 1

- ^

- ^

- AHD staff 2022b

- Walton 2005, pp. 59, 64

- ^

- ^

- ^ Steup & Neta 2020, § 2. What Is Knowledge?

- ^ Allen 2005

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2020, Lead Section

- Truncellito 2023, Lead Section

- Moser 2005, p. 3

- ^

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 99

- Hetherington 2022a, § 2. Knowledge as a Kind

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, Lead Section

- Hannon 2021, Knowledge, Concept of

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 92, 96–97

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, Lead Section

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 96

- Gupta 2021

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- ^

- Pritchard 2013, 3 Defining knowledge

- McCain 2022, Lead Section, § 2. Chisholm on the Problem of the Criterion

- Fumerton 2008, pp. 34–36

- ^

- Stroll 2023, § The Origins of Knowledge, § Analytic Epistemology

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- García-Arnaldos 2020, p. 508

- ^

- Hetherington, § 8. Implications of Fallibilism: No Knowledge?

- Hetherington 2022a, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Black 2002, pp. 23–32

- ^

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 3. Warrant

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 99–100

- ^

- Allen 2005, Lead Section, § Gettierology

- Parikh & Renero 2017, pp. 93–102

- Chappell 2019, § 8. Third Definition (D3): 'Knowledge Is True Judgement With an Account': 201d–210a

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.1 The Truth Condition

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That, § 5. Understanding Knowledge?

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ^

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.2 The Belief Condition

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 93

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition, § 6. Doing Without Justification?

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 3. Warrant

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 100

- ^

- Klein 1998, § 2. Propositional Knowledge Is Not Mere True Belief, § 3. Warrant

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5a. The Justified-True-Belief Conception of Knowledge, § 6e. Mere True Belief

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition

- Klein 1998, § 3. Warrant

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5a. The Justified-True-Belief Conception of Knowledge, § 6e. Mere True Belief

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition, § 6.1 Reliabilist Theories of Knowledge

- Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism, § 6. Externalism

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5a. The Justified-True-Belief Conception of Knowledge, § 7. Knowing’s Point

- ^ Hetherington 2022, Lead Section, § Introduction

- ^

- Klein 1998, § 5. Defeasibility Theories

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5. Understanding Knowledge?

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 100

- ^

- Rodríguez 2018, pp. 29–32

- Goldman 1976, pp. 771–773

- Sudduth 2022

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 10.2 Fake Barn Cases

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 10.2 Fake Barn Cases

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 4. No False Lemmas, § 5. Modal Conditions, § 6. Doing Without Justification?

- ^ Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.3 Knowing Facts

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- Durán & Formanek 2018, pp. 648–650

- ^ McCain, Stapleford & Steup 2021, p. 111

- ^

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5c. Questioning the Gettier Problem, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Kraft 2012, pp. 49–50

- ^

- Ames, Yajun & Hershock 2021, pp. 86–87

- Legg & Hookway 2021, § 4.2 Inquiry

- Baggini & Southwell 2016, p. 48

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 93–94, 104–105

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.3 Knowing Facts

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Barnett 1990, p. 40

- Lilley, Lightfoot & Amaral 2004, pp. 162–163

- ^ Allen 2005, Lead Section

- ^

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- Faber, Maruster & Jorna 2017, p. 340

- Gertler 2021, Lead Section

- Rescher 2005, p. 20

- ^

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ^ Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That, § 1c. Knowledge-Wh

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1c. Knowledge-Wh

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ^ Hetherington 2022a, § 1c. Knowledge-Wh

- ^

- Morrison 2005, p. 371

- Reif 2008, p. 33

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 93

- ^ Woolfolk & Margetts 2012, p. 251

- ^ a b Pritchard 2013, 1 Some preliminaries

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- Stanley & Willlamson 2001, pp. 411–412

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1d. Knowing-How

- Pritchard 2013, 1 Some preliminaries

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.2 Knowing How

- Pavese 2022, Lead Section, § 6. The Epistemology of Knowledge-How

- ^ Pavese 2022, § 7.4 Knowledge-How in Preverbal Children and Nonhuman Animals.

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- Stroll 2023, § St. Anselm of Canterbury

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ^

- Peels 2023, p. 28

- Heydorn & Jesudason 2013, p. 10

- Foxall 2017, p. 75

- Hasan & Fumerton 2020

- DePoe 2022, Lead Section, § 1. The Distinction: Knowledge by Acquaintance and Knowledge by Description

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- ^

- Hasan & Fumerton 2020, introduction

- Haymes & Özdalga 2016, pp. 26–28

- Miah 2006, pp. 19–20

- Alter & Nagasawa 2015, pp. 93–94

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- ^

- Stroll 2023, § A Priori and a Posteriori Knowledge

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- Russell 2020, Lead Section

- ^

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- Moser 2016, Lead Section

- ^ Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- ^

- Russell 2020, Lead Section

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- ^ Moser 2016, Lead Section

- ^

- Baehr 2022, § 1. An Initial Characterization, § 4. The Relevant Sense of 'Experience'

- Russell 2020, § 4.1 A Priori Justification Is Justification That Is Independent of Experience

- ^

- Baehr 2022

- Russell 2020, § 4.1 A Priori Justification Is Justification That Is Independent of Experience

- ^

- Woolf 2013, pp. 192–193

- Hirschberger 2019, p. 22

- ^

- Moser 1998, § 2. Innate concepts, certainty and the a priori

- Markie 1998, § 2. Innate ideas

- O'Brien 2006, p. 31

- Markie & Folescu 2023, § 2. The Intuition/Deduction Thesis

- ^ Baehr 2022, § 1. An Initial Characterization, § 6. Positive Characterizations of the A Priori

- ^

- Gertler 2021, Lead Section, § 1. The Distinctiveness of Self-Knowledge

- Gertler 2010, p. 1

- McGeer 2001, pp. 13837–13841

- ^

- Gertler 2021a

- Morin & Racy 2021, pp. 373–374

- Kernis 2013, p. 209

- ^

- Wilson 2002, pp. 3–4

- Reginster 2017, pp. 231–232

- ^

- Evans & Foster 2011, pp. 721–725

- Rescher 2005, p. 20

- Cox & Raja 2011, p. 134

- Leondes 2001, p. 416

- ^

- ^ Schneider & McGrew 2022, pp. 115–116

- ^

- ^ a b

- ^ Barnett 2006, pp. 146–147

- ^ Hunter 2009, pp. 151–153

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Stroll 2023, § Occasional and Dispositional Knowledge

- Bartlett 2018, pp. 1–2

- Schwitzgebel 2021

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Kern 2017, pp. 8–10, 133

- Spaulding 2016, pp. 223–224

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3. Ways of Knowing

- Stroll 2023, § The Origins of Knowledge

- O'Brien 2022, Lead Section

- ^

- Bertelson & Gelder 2004, pp. 141–142

- Martin 1998, Lead Section

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.1 Perception, § 5.5 Testimony

- ^

- Khatoon 2012, p. 104

- Martin 1998, Lead Section

- ^ Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.2 Introspection

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3. Ways of Knowing

- Stroll 2023, § The Origins of Knowledge

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.3 Memory

- Audi 2002, pp. 72–75

- ^

- Gardiner 2001, pp. 1351–1352

- Michaelian & Sutton 2017

- ^ Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.3 Memory

- ^

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3d. Knowing by Thinking-Plus-Observing

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.4 Reason

- ^

- Audi 2002, pp. 85, 90–91

- Markie & Folescu 2023, Lead Section, § 1. Introduction

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.5 Testimony

- Leonard 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Reductionism and Non-Reductionism

- Green 2022, Lead Section

- ^

- Rescher 2009, pp. ix, 1–2

- Rescher 2005a, p. 479

- Markie & Folescu 2023, § 1. Introduction

- ^

- Markie & Folescu 2023, § 1. Introduction

- Rescher 2009, pp. 2, 6

- Stoltz 2021, p. 120

- ^ Rescher 2009, p. 6

- ^

- Rescher 2009, pp. 2, 6

- Rescher 2009a, pp. 140–141

- ^

- Rescher 2009, pp. 10, 93

- Rescher 2009a, pp. x–xi, 57–58

- Dika 2023, p. 163

- ^

- Rescher 2009, pp. 3, 9, 65–66

- Rescher 2009a, pp. 32–33

- Weisberg 2021, § 4. Fourth Case Study: The Limits of Knowledge

- ^ Weisberg 2021, § 4.2 The Knowability Paradox (a.k.a. the Church-Fitch Paradox)

- ^ Kreeft & Tacelli 2009, p. 371

- ^

- Sinnott-Armstrong 2019, Lead Section, § 1. Varieties of Moral Skepticism, § 2. A Presumption Against Moral Skepticism?

- Sayre-McCord 2023, § 5. Moral Epistemology

- ^

- McCormick, § 4. Kant's Transcendental Idealism

- Williams 2023, Lead Section, § 1. Theoretical reason: reason’s cognitive role and limitations

- Blackburn 2008, p. 101

- ^

- Rutten 2012, p. 189

- Yanofsky 2013, pp. 185–186

- ^ Yanofsky 2013, pp. 161–164

- ^

- Windt 2021, § 1.1 Cartesian Dream Skepticism

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- ^ a b Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ^

- Hetherington 2022a, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ^ Stroll 2023, § Skepticism

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.2 Responses to the Closure Argument

- Lycan 2019, pp. 21–22, 5–36

- ^

- McDermid 2023

- Misak 2002, p. 53

- Hamner 2003, p. 87

- ^

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ^

- Attie-Picker 2020, pp. 97–98

- Perin 2020, pp. 285–286

- ^

- Hetherington, Lead Section, § 9. Implications of Fallibilism: Knowing Fallibly?

- Rescher 1998, Lead Section

- Legg & Hookway 2021, 4.1 Skepticism versus Fallibilism

- ^

- Legg & Hookway 2021, 4.1 Skepticism versus Fallibilism

- Hookway 2012, pp. 39–40

- ^

- Hasan & Fumerton 2018, Lead Section, 2. The Classical Analysis of Foundational Justification

- Fumerton 2022, § Summary

- ^ a b c

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4. The Structure of Knowledge and Justification

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- ^

- ^

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4.1 Foundationalism

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- ^

- ^

- Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4. The Structure of Knowledge and Justification

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- George 2021, § 1.2 Against Foundationalism, § 1.3 The Hermeneutical Circle

- ^ a b

- Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4. The Structure of Knowledge and Justification

- ^

- ^ Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- ^

- Degenhardt 2019, pp. 1–6

- Pritchard 2013, 2 The value of knowledge

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- ^ Pritchard 2013, 2 The value of knowledge

- ^

- ^

- Lemos 1994, pp. 88–89

- Bergström 1987, pp. 53–55

- ^

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- ^

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022

- Plato 2002, pp. 89–90, 97b–98a

- ^ Olsson 2011, p. 875

- ^ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, Lead Section, § 6. Other Accounts of the Value of Knowledge

- ^

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022

- Olsson 2011, p. 874

- Pritchard 2007, pp. 85–86

- ^ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 2. Reliabilism and the Meno Problem, § 3. Virtue Epistemology and the Value Problem

- ^ Turri, Alfano & Greco 2021

- ^ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 2. Reliabilism and the Meno Problem

- ^

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 3. Virtue Epistemology and the Value Problem

- Olsson 2011, p. 877

- Turri, Alfano & Greco 2021, § 6. Epistemic Value

- ^

- Stehr & Adolf 2016, pp. 483–485

- Powell 2020, pp. 132–133

- Meirmans et al. 2019, pp. 754–756

- ^

- ^ Degenhardt 2019, pp. 1–6

- ^ a b

- Pritchard 2013, pp. 115–118, 11 Scientific Knowledge

- Moser 2005, p. 385

- ^ Moser 2005, p. 386

- ^ Hepburn & Andersen 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Overview and organizing themes

- ^

- ^

- Dodd, Zambetti & Deneve 2023, pp. 11–12

- Hatfield 1998

- Hepburn & Andersen 2021, Lead Section, § 6.1 "The scientific method" in science education and as seen by scientists

- ^

- Cohen 2013, p. xxv

- Myers 2009, p. 8

- Repko 2008, p. 200

- ^

- Repko 2008, p. 200

- Hatfield 1998, § 3. Scientific Method in Scientific Practice

- Mertler 2021, pp. 100–101

- Myers 2009, p. 8

- ^

- ^

- Mertler 2021, pp. 88–89

- Travers 2001, pp. 1–2

- ^

- Howell 2013, pp. 193–194

- Travers 2001, pp. 1–2

- Klenke 2014, p. 123

- ^

- Schoonenboom & Johnson 2017, pp. 107–108

- Shorten & Smith 2017, pp. 74–75

- ^

- Pritchard 2013, pp. 123–125, 11 Scientific Knowledge

- Niiniluoto 2019

- ^ Bird 2022, § 6.2 Incommensurability

- ^ Plantinga 2018, pp. 222–223

- ^

- Flynn 2000, pp. 83–84

- Clegg 2022, p. 14

- Mahadevan 2007, p. 91

- Gauch 2003, p. 88

- ^

- Burke 2015, 1. Knowledges and Their Histories: § History and Its Neighbours, 3. Processes: § Four Stages, 3. Processes: § Oral Transmission

- Doren 1992, pp. xvi–xviii

- Daston 2017, pp. 142–143

- Mulsow 2018, p. 159

- ^

- Bowen, Gelpi & Anweiler 2023, § Introduction, Prehistoric and Primitive Cultures

- Bartlett & Burton 2007, p. 15

- Fagan & Durrani 2016, p. 15

- Doren 1992, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiii–xxiv, 3–4

- Friesen 2017, pp. 17–18

- Danesi 2013, pp. 168–169

- Steinberg 1995, pp. 3–4

- Thornton & Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ^

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiii–xxiv, 3–4, 29–30

- Conner 2009, p. 81

- ^

- Burke 2015, 2. Concepts: § Authorities and Monopolies

- Kuhn 1992, p. 106

- Thornton & Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ^

- ^

- Johnson & Stearns 2023, pp. 5, 43–44, 47

- Esposito 2003, Madrasa

- ^ Trefil 2012, pp. 49–51

- ^ Aqil, Babekri & Nadmi 2020, p. 156

- ^ Cosman & Jones 2009, p. 148

- ^ Gilliot 2018, p. 81

- ^

- Bowen, Gelpi & Anweiler 2023, § The Development of the Universities

- Kemmis & Edwards-Groves 2017, p. 50

- ^ Power 1970, pp. 243–244

- ^

- Celenza 2021, pp. ix–x

- Black & Álvarez 2019, p. 1

- ^

- Steinberg 1995, p. 5

- Danesi 2013, pp. 169–170

- ^

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiv–xxv, 184–185

- Thornton & Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ^

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiv–xxv, 213–214

- Thornton & Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ^

- Thornton & Lanzer 2018, p. 8

- Danesi 2013, pp. 178–181

- ^ Danesi 2013, pp. 178–181

- ^ Clark 2022, Lead Section, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- ^ a b Penelhum 1971, 1. Faith, Scepticism and Philosophy

- ^

- Clark 2022, Lead Section

- Forrest 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Simplifications

- ^

- Clark 2022, Lead Section, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- Forrest 2021, Lead Section, § 2. The Rejection of Enlightenment Evidentialism

- Dougherty 2014, pp. 97–98

- ^

- Clark 2022, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- Forrest 2021, Lead Section, 2. The Rejection of Enlightenment Evidentialism

- ^ Clark 2022, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- ^ Stevenson 2003, pp. 72–73

- ^

- Paden 2009, pp. 225–227

- Paden 2005, Lead Section

- ^

- Carson & Cerrito 2003, p. 164

- Delahunty & Dignen 2012, p. 365

- Blayney 1769, Genesis

- ^

- Legge 2017, p. 181

- Van Nieuwenhove 2020, p. 395

- ^

- Campo 2009, p. 515

- Swartley 2005, p. 63

- ^

- Burton 2002, pp. 326–327

- Chaudhary 2017, pp. 202–203

- Chaudhary 2017a, pp. 1373–1374

- ^

- Chaudhary 2017, pp. 202–203

- Chaudhary 2017a, pp. 1373–1374

- ^