Islam in Malawi

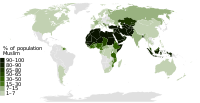

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

| |

Islam is the second largest religion in Malawi behind Christianity. Nearly all of Malawi's Muslims adhere to Sunni Islam.[1] Though difficult to assess,[2] according to the CIA Factbook, in 2018 about 13.8% of the country's population was Muslim.[3] Muslim organisations in the country claim a figure of 15-20%.[4] According to the latest census (2018), Muslims make up 13.8% (2,426,754) of the country's population.[5][6] According to the Malawi Religion Project[7] run by the University of Pennsylvania, in 2010 approximately 19.6% of the population was Muslim, concentrated mostly in the Southern Region.[8]

History

[edit]Islam arrived in Malawi with the Arab and Swahili traders who traded in ivory, gold and later on slaves beginning from 15th century. It is also argued that Islam first arrived in Malawi through traders from the Kilwa Sultanate.[9] Two Muslim teachers, Shayhks Abdallah Mkwanda and Sabiti Ngaunje, also played an important role in the spread of Islam.[10] According to UNESCO, the first mosque was built by Swahili-Arab ivory traders.[11]

During the colonial era, the authorities in the country feared that Islam posed the greatest threat, as an ideology of resistance, to their rule.[12] This view was shared by Christian missionaries, who greatly feared that Islam could unite Africans in hostilities and uprisings against colonial rule.[13]

The Yao converted to Islam in the 19th century, comprising the largest Muslim group in Malawi since.[14] Some Chewa also converted to Islam during the same period.[15]

The 1970s witnessed the start of an Islamic revival among Muslims in Malawi, as well as among Muslims across the globe.[16] Recently, Muslim groups have engaged in missionary work in Malawi. Much of this is performed by the African Muslim Agency, based in Kuwait. The Kuwait-sponsored AMA has translated the Qur'an into Chichewa (Cinyanja),[17] one of the official languages of Malawi, and has engaged in other missionary work in the country. There are thought to be about 800 jumu'ah mosques in the country, with at least one or two to be found in nearly every town.[18] There are also several Islamic schools[19] and a broadcasting station called Radio Islam.[20] A major Muslim center of learning exists in Mpemba, outside of Blantyre, funded mainly by money from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.[13]

Demography

[edit]A large number of Muslims in Malawi come from the Yao people,[21] who are described as "the most important source of Islam in the country".[22] Even before their conversion to Islam, many Yao chiefs used Swahili Muslims as scribes and advisers.[23] As a result of their strong trading contacts with Swahili-Arabs, many Yao adopted Islam and the two groups had cases of intermarriages in the past.[24] The Yao form the largest majority south and east of Lake Malawi.[25] Muslims can also be found among other groups, such as the lakeside Chewa people[10] and Indian[26] and other Asian Malawians.[2] Muslims in the country have been described as a "vocal and powerful community."[13]

In general, most Malawian Muslims are Sunni. According to a source, 72 percent of Muslims are ethnic Yao and 16 percent are ethnic Chewa.[27] Most Muslims of African descent in Malawi are Sunni and belong to the Shafi'i madhhab. Meanwhile, Muslims of Asian descent in Malawi are also mostly Sunni and belong to the Hanafi madhhab. Additionally, there is a small number of Shiites among people of Lebanese origin in Malawi.[28]

According to the 2018 census, over half of Malawian Muslims live in Mangochi and Machinga district. Muslims comprised 72.6% of the population in Mangochi district and 66.9% of the population in Machinga.[28]

Distribution

[edit]| Area | Muslim Population | Total Population | Muslim Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malawi | 2,426,754 | 17,563,749 | 13.82% |

| Northern | 31,571 | 2,289,780 | 1.38% |

| Chitipa | 181 | 234,927 | 0.08% |

| Karonga | 5,035 | 365,028 | 1.38% |

| Nkhata Bay | 3,079 | 284,681 | 1.08% |

| Rumphi | 2,957 | 229,161 | 1.29% |

| Mzimba | 10,996 | 940,184 | 1.17% |

| Likoma | 329 | 14,527 | 2.26% |

| Mzuzu City | 8,994 | 221,272 | 4.06% |

| Central | 516,200 | 7,523,340 | 6.86% |

| Kasungu | 18,769 | 842,953 | 2.23% |

| Nkhotakota | 94,487 | 393,077 | 24.04% |

| Ntchisi | 1,556 | 317,069 | 0.49% |

| Dowa | 7,038 | 772,569 | 0.91% |

| Salima | 146,605 | 478,346 | 30.65% |

| Lilongwe | 27,992 | 1,637,583 | 1.71% |

| Mchinji | 14,200 | 602,305 | 2.36% |

| Dedza | 78,868 | 830,512 | 9.50% |

| Ntcheu | 15,987 | 659,608 | 2.42% |

| Lilongwe City | 110,698 | 989,318 | 11.19% |

| Southern | 1,878,983 | 7,750,629 | 24.24% |

| Mangochi | 834,644 | 1,148,611 | 72.67% |

| Machinga | 492,560 | 735,438 | 66.98% |

| Zomba | 147,123 | 746,724 | 19.70% |

| Chiradzulu | 40,342 | 356,875 | 11.30% |

| Blantyre | 35,955 | 451,220 | 7.97% |

| Mwanza | 1,678 | 130,949 | 1.28% |

| Thyolo | 15,291 | 721,456 | 2.12% |

| Mulanje | 38,135 | 684,107 | 5.57% |

| Phalombe | 7,867 | 429,450 | 1.83% |

| Chikwawa | 9,451 | 564,684 | 1.67% |

| Nsanje | 5,825 | 299,168 | 1.95% |

| Balaka | 152,298 | 438,379 | 34.74% |

| Neno | 2,029 | 138,291 | 1.47% |

| Zomba City | 14,877 | 105,013 | 14.17% |

| Blantyre City | 80,908 | 800,264 | 10.11% |

Notable Muslims

[edit]An important Malawian Muslim is Bakili Muluzi, the first (and only) freely elected President of Malawi from 1994 to 2004. Another important Malawian Muslim was the late Sidik Mia, who was a minister in the Tonse Alliance elected in the 2020 Malawi tripatite Elections and died in 2021.

Cassim Chilumpha is a prominent politician that has served as Vice-President of Malawi.[15] Atupele Muluzi, son of Bakili Muluzi, is also a notable politician who is Muslim.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Klaus Fiedler (2015). Conflicted Power in Malawian Christianity: Essays Missionary and Evangelical from Malawi (illustrated ed.). Mzuni Press. pp. 180–1. ISBN 9789990802498.

- ^ a b Arne S. Steinforth (2009). Troubled Minds: On the Cultural Construction of Mental Disorder and Normality in Southern Malawi. Peter Lang. p. 79. ISBN 9783631587171.

- ^ CIA statistics

- ^ Owen J. M. Kalinga (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi (revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 202. ISBN 9780810859616.

- ^ Klaus Fiedler (2015). Conflicted Power in Malawian Christianity: Essays Missionary and Evangelical from Malawi (illustrated ed.). Mzuni Press. p. 213. ISBN 9789990802498.

- ^ a b "2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census". www.nsomalawi.mw. Archived from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ "The Malawi Religion Project (MRP) | Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH)". Malawi.pop.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ HANS-PETER KOHLER. "Cohort Profile: The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH)". Repository.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ^ Arne S. Steinforth (2009). Troubled Minds: On the Cultural Construction of Mental Disorder and Normality in Southern Malawi. Peter Lang. p. 78. ISBN 9783631587171.

- ^ a b Owen J. M. Kalinga (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi (revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 200. ISBN 9780810859616.

- ^ "Malawi Slave Routes and Dr. David Livingstone Trail".

- ^ John McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859-1966 (illustrated ed.). Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 142. ISBN 9781847010506.

- ^ a b c Owen J. M. Kalinga (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi (revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 201. ISBN 9780810859616.

- ^ Brenner, Louis (1993). Muslim Identity and Social Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. Indiana University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-253-31271-6.

- ^ a b c Haron, Muhammed (2020), "Southern Africa's Muslim Communities: Selected Profiles", The Palgrave Handbook of Islam in Africa, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 163–202, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45759-4_10, ISBN 978-3-030-45758-7, S2CID 226444450, retrieved 2023-02-10

- ^ Klaus Fiedler (2015). Conflicted Power in Malawian Christianity: Essays Missionary and Evangelical from Malawi (illustrated ed.). Mzuni Press. p. 202. ISBN 9789990802498.

- ^ "Proseletysation in Malawi". Archived from the original on 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ David Mphande (2014). Oral Literature and Moral Education among the Lakeside Tonga of Northern Malawi (illustrated, reprint ed.). Mzuni Press. p. 132. ISBN 9789990802443.

- ^ Islamic organisations in Malawi

- ^ Harri Englund (2011). Christianity and Public Culture in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780821443668.

- ^ Brenner, Louis, ed. (1993). Muslim Identity and Social Change in Sub-Saharan Africa (illustrated ed.). Indiana University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780253312716.

- ^ Timothy Insoll (2003). The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 393. ISBN 9780521657020.

- ^ I. C. Lamba (2010). Contradictions in Post-war Education Policy Formulation and Application in Colonial Malawi 1945-1961: A Historical Study of the Dynamics of Colonial Survival. African Books Collective. p. 154. ISBN 9789990887945.

- ^ Owen J. M. Kalinga (2012). Historical Dictionary of Malawi (revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 155. ISBN 9780810859616.

- ^ Naʻīm, ʻAbd Allāh Aḥmad, ed. (2002). Islamic Family Law in A Changing World: A Global Resource Book (illustrated ed.). Zed Books. p. 189. ISBN 9781842770931.

- ^ Naʻīm, ʻAbd Allāh Aḥmad, ed. (2002). Islamic Family Law in A Changing World: A Global Resource Book (illustrated ed.). Zed Books. p. 194. ISBN 9781842770931.

- ^ "2014 Report on International Religious Freedom - Malawi".

- ^ a b "Malawi". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2022-01-30.

Further reading

[edit]- David S. Bone (2000). Malawi's Muslims: Historical Perspectives. African Books Collective. p. 220. ISBN 9789990816150.

- David S. Bone (2021). Introduction to Islam for Malawi. African Books Collective. p. 174. ISBN 9789996060908.

- Ian D. Dicks (2012). An African Worldview: The Muslim Amacinga Yawo of Southern Malaŵi. African Books Collective. p. 510. ISBN 9789990887518.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch