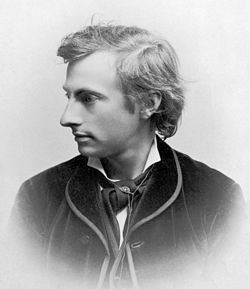

Karl Adolph Gjellerup

Karl Adolph Gjellerup | |

|---|---|

Karl Adolph Gjellerup | |

| Born | 2 June 1857 Roholte vicarage at Præstø, Denmark |

| Died | 11 October 1919 (aged 62) Klotzsche, Germany |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1917 (shared) |

Karl Adolph Gjellerup (Danish: [ˈkʰɑˀl ˈɛːˌtʌlˀf ˈkelˀəʁɔp]; 2 June 1857 – 11 October 1919) was a Danish poet and novelist who together with his compatriot Henrik Pontoppidan won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1917. He is associated with the Modern Breakthrough period of Scandinavian literature. He occasionally used the pseudonym Epigonos.

Biography

[edit]Youth and debut

[edit]Gjellerup was the son of a vicar in Zealand who died when his son was three years. Karl Gjellerup was raised then by the uncle of Johannes Fibiger, he grew up in a national and romantic idealistic atmosphere. In the 1870s he broke with his background and at first he became an enthusiastic supporter of the naturalist movement and Georg Brandes, writing audacious novels about free love and atheism. Strongly influenced by his origin he gradually left the Brandes line and 1885 he broke totally with the naturalists, becoming a new romanticist. A central trace of his life was his Germanophile attitude, he felt himself strongly attracted to German culture (his wife was a German) and 1892 he finally settled in Germany, which made him unpopular in Denmark on both the right and left wing. As years passed he totally identified with the German Empire, including its war aims 1914–18.

Among the early works of Gjellerup must be mentioned his most important novel Germanernes Lærling (1882, i.e. The Germans' Apprentice), a partly autobiographic tale of the development of a young man from being a conformist theologian to a pro-German atheist and intellectual, and Minna (1889), on the surface, a love story but more of a study in woman's psychology. Some Wagnerian dramas show his growing romanticist interests. An important work is the novel Møllen (1896, i. e. The Mill), a sinister melodrama of love and jealousy.

Later years

[edit]In his last years he was clearly influenced by Buddhism and Oriental culture. His critically acclaimed work Der Pilger Kamanita/Pilgrimen Kamanita (1906, i.e. The Pilgrim Kamanita) has been called 'one of the oddest novels written in Danish'. It features the journey of Kamanita, an Indian merchant's son, from earthly prosperity and carnal romance, through the ups and downs of the world's way, a chance meeting with a stranger monk (who, unbeknownst to Kamanita, was actually Gautama Buddha), death, and reincarnation towards nirvana. In Thailand, which is a Buddhist country, the Thai translation of The Pilgrim Kamanita co-translated by Phraya Anuman Rajadhon was formerly used as part of the school textbooks.

Den fuldendtes hustru (1907, i.e. The wife of the perfect) is a versified drama, inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy, about Buddha's earthly life as Siddharta, being inhibited in his spiritual efforts by his wife, Yasodhara. The giant novel Verdensvandrerne (1910, i.e. The world roamers) takes its contemporary starting point in a German female academic on a study tour in India, but evolves across chronological levels, in which characters re-experience what has happened in former eons, thus featuring souls roaming from one incarnation to another.

Rudolph Stens Landpraksis (1913, i.e. The country practice of [physician] Rudolph Sten) is set in the rural Zealand of Gjellerup's youth. The main character develops from a liberal, superficial outlook on life, including youthful romantical conflicts, through years of reflection and ascetic devotion to duty towards a more mature standpoint, hinting at the author's own course of life.

Das heiligste Tier (1919, i.e. The holiest animal) was Gjellerup's last work. Having elements of self-parody, it is regarded as his only attempt at humour. It is a peculiar mythological satire in which animals arrive at their own Elysium after death. These include the snake that killed Cleopatra, Odysseus' dog Argos, Wisvamitra (the holy cow of India), the donkey of Jesus and the horses of various historical commanders in field. The assembly select, after discussion, Buddha's horse Kantaka as the holiest of animals, but it has left without a trace to follow its master to nirvana.

Aftermath

[edit]In Denmark, Gjellerup's Nobel award was received with little enthusiasm. He had long been regarded as a German writer. During various stages of his career, he had made himself unpopular with both the naturalist left surrounding Georg Brandes and the conservative right. Gjellerup's nomination for the Nobel prize did nevertheless receive Danish support. Because Sweden was neutral during World War I, the divided prize did not arouse political speculations about partial decision, but showed on the other hand allegiance between the Nordic neighbors.

Today Gjellerup is almost forgotten in Denmark. In spite of this, however, literary historians normally regard him as an honest seeker after truth.

Gjellerup's works have been translated into several languages, including German (often translated by himself), Swedish, English, Dutch, Polish, Thai and others.[citation needed] The Pilgrim Kamanita is his most widely translated book, having been published in several European countries and the United States.[citation needed] In Thailand, a Buddhist country, the first half of the Thai translation of Kamanita have been used in secondary school textbooks.[citation needed]

Biographies

[edit]- Georg Nørregård: Karl Gjellerup – en biografi, 1988 (in Danish)

- Olaf C. Nybo: Karl Gjellerup – ein literarischer Grenzgänger des Fin-de-siècle, 2002 (in German)

- Article in Vilhelm Andersen: Illustreret dansk Litteraturhistorie, 1924–34 (in Danish)

- Article in Hakon Stangerup: Dansk litteraturhistorie, 1964–66 (in Danish)

External links

[edit]- Works by Karl Adolph Gjellerup in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Karl Gjellerup at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Karl Adolph Gjellerup at the Internet Archive

- Works by Karl Adolph Gjellerup at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Karl Adolph Gjellerup at Open Library

- Knud B. Gjesing: Karl Gjellerup, portrait of the author, Archive for Danish Literature, Danish Royal Library (in Danish) (pdf)

- List of Works

- Karl Adolph Gjellerup on Nobelprize.org

- MyNDIR (My Norse Digital Image Repository) Illustrations from manuscripts and early print books by Karl Adolph Gjellerup.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch