Kolathunadu

Kola Swarupam Kolathunadu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 6th century BCE (conventional dating)–modern era | |||||||||

Ezhimala, early historic headquarters of Kola Swaroopam | |||||||||

| Capital | Ezhimala, Valapattanam, Chirakkal and various other capitals | ||||||||

| Common languages | Malayalam | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||

| Kolattiri | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | c. 6th century BCE (conventional dating) | ||||||||

• Disestablished | modern era | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Kerala |

|---|

Kolattunādu (Malayalam: [koːlɐt̪ːun̪aːɖə̆]) (Kola Swarupam, as Kingdom of Cannanore in foreign accounts, Chirakkal (Chericul) in later times) was one of the four most powerful kingdoms on the Malabar Coast during the arrival of the Portuguese Armadas in India, along with Zamorin, the kingdom of Cochin and Quilon. Kolattunādu had its capital at Ezhimala and was ruled by the Kolattiri royal family and roughly comprised the North Malabar region of Kerala state in India. Traditionally, Kolattunādu is described as the land lying between the Chandragiri river in the north and the Korappuzha river in the south.[1] The Kolathunadu (Kannur) kingdom at the peak of its power, reportedly extended from the Netravati River (Mangalore) in the north to Korapuzha (Kozhikode) in the south with the Arabian Sea on the west and Kodagu hills on the eastern boundary, also including the isolated islands of Lakshadweep in the Arabian Sea.[2]

The ruling house of Kolathunādu, known as the Kolathiris, were descendants of the Mushaka royal family, an ancient dynasty of Kerala, and rose to become one of the major political powers in the Kerala region, after the disappearance of the Cheras of Mahodayapuram and the Pandyan Dynasty in the 12th century AD.[3][4]

The Kolathiris trace their ancestry back to the ancient Mushika kingdom (Ezhimala kingdom, Eli-nadu) of the Tamil Sangam age. After King Nannan of the Mushika dynasty was killed in a battle against the Cheras, the chronicled history of the dynasty is obscure, except for a few indirect references here and there. However, it is generally agreed among conventional scholars that the Kolathiris are descendants of King Nannan, and later literary works point towards kings such as Vikramaraman, Jayamani, Valabhan and Srikandan of the Mushika Dynasty. The Indian anthropologist Ayinapalli Aiyappan states that a powerful and warlike clan of the Bunt community of Tulu Nadu was called Kola Bari and the Kolathiri Raja of Kolathunadu was a descendant of this clan.[5] The more famous Travancore royal family is a close cousin dynasty of the Kolathiris.[6][7][8]

Though the Kolattiris were generally credited with superior political authority over the zone between the kingdoms of Canara and Zamorin's Calicut, their political influence was more or less confined to Kolattunādu.[9][10]

Ezhimala, their ancient capital, was one of the most important trading centres on the Malabar coast along with Quilon and Calicut, and found mention in the writings of Ibn Battuta, Marco Polo and Wang Ta-Yuan. In the course of time, their territories were divided into a number of petty vassal principalities, chief among them Cannanore and Laccadives, Cotiote and Wynad, Cartinad (Badagara), Irvenaad, and Randaterra. The so-called "Five Friendly Northern Rulers" (Nilesvaram, Kumbla, Vitalh, Bangor, and Chowtwara) were contiguous to Kolattnad, north of the Kavvayi river. They engaged in frequent rivalry with their powerful neighbors in the south, the Zamorins of Calicut—a permanent feature of Kerala history. The caste restrictions and Korapuzha boundary between North Malabar and the Zamorin's kingdom were established after their rivalry. Some historical accounts also suggest that the Kolathunad kingdom was friendly with the Travancore kingdom and the Tulu kingdom.[11]

Cherusseri Namboothiri (c. 1375-1475 AD), the author of Krishna Gatha, a landmark in the development of Malayalam literature, lived in the court of Udayavarman Kolattiri, one of the kings of the Kolathiri dynasty.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Background

[edit]The origin of the Ezhimala rulers, the Mushaka kingdom, and Kolathunad is unclear in terms of conventional history.

Christian missionary Samuel Mateer opined: "There seems reason to believe that the whole of the kings of Malabar also, notwithstanding the pretensions set up for them of late by their dependents, belong to the same great body, and are homogeneous with the mass of the people called Nairs, So Namboodiris were reluctant to give Kshtriyahood to all the Nair lords, In 1617 A.D Kolathiri Rāja, Udayavarman, wished to further promote himself to Soma Kshatriya by performing Hiranya-garbhā,[12][13] which the Nambũdiris refused. Consequently, Udayavarman brought 237 Brahmin families (Sāgara Dwijas) from Gokarnam and settled them in five Desams. (Cheruthāzham, Kunniriyam, Arathil, Kulappuram and Vararuchimangalam of Perinchelloor Grāmam). The latter adopted Nambũdiri customs and performed Hiranya-garbhā and conferred Kshatriyahood on the former.[13][14]

Ezhimala rulers

[edit]

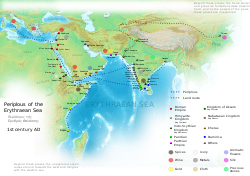

The ancient port of Naura, which is mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as a port somewhere north of Muziris is identified with Kannur.[15]

Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) states that the port of Tyndis was located at the northwestern border of Keprobotos (Chera dynasty).[16] The North Malabar region, which lies north of the port at Tyndis, was ruled by the kingdom of Ezhimala during Sangam period.[17] According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a region known as Limyrike began at Naura and Tyndis. However the Ptolemy mentions only Tyndis as the Limyrike's starting point. The region probably ended at Kanyakumari; it thus roughly corresponds to the present-day Malabar Coast. The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces.[18] Pliny the Elder mentioned that Limyrike was prone by pirates.[19] The Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned that the Limyrike was a source of peppers.[20][21]

During the Sangam period, the early centuries of the Christian era, both present-day Kerala and Tamil Nadu were considered part of a common cultural realm and a common geographical settlement pattern, in spite of being under distinct political entities.[22] More specifically, Tamil anthologies of the early Christian era make no sharp cultural or social distinction between the Pandyas, the Cheras, or the Cholas, and the Velir chiefs, all operating within a common cultural and geographical milieu. Also later, the Hindu temples on the western coast were also included in the sacred geography of the Tamil Bhakti movement and were profusely praised by the Alwars and Nayanars, the main proponents of the movement, in their verses.[23]

In the Tamil Sangam Age, northern Malabar like the rest of present-day Kerala, Tulu Nadu, Coorg, and some parts of Tamil Nadu was under the rule of the Cheras. A branch of the Cheras (and others like the Pandyas and Cholas) with its capital at Ezhil mala (and with second capital at Pazhi), known as the Mushika dynasty ruled the area on behalf of the Cheras. Ezhil mala (Mount Deli in European accounts) and its neighboring regions became dynamic centers of sociopolitical activities in the early centuries of the Christian era.[24] The Ezhil mala kingdom (Konka-nam, a part of the Puzhi-nadu) comprised practically the whole of the ypresent Kannur and Wayanad districts and a portion of the Tulu country and parts of Coorg and Gudalur as well. This was the north-westernmost Tamil speaking area of the ancient Tamil country. Ezhimala kingdom based at Ezhimala had jurisdiction over two Nadus - coastal Poozhinadu and the hilly eastern Karkanadu. According to the works of Sangam literature, Poozhinadu consisted much of the coastal belt between Mangalore and Kozhikode.[25] Karkanadu consisted of Wayanad-Gudalur, a hilly region with parts of Kodagu (Coorg).[26]

It is said that Nannan, the most renowned ruler of Ezhimala dynasty, took refuge at Wayanad hills in the 5th century CE when he was lost to Cheras, just before his death in a battle, according to the Sangam works.[26] Ezhimala kingdom was succeeded by the Mushika dynasty in the early medieval period, most possibly due to the migration of Tuluva Brahmins from Tulu Nadu. The Kolathunadu (Kannur) kingdom, who were the descendants of the Mushika dynasty, at the peak of its power reportedly extended from Netravati River (Mangalore) in the north[2] to Korapuzha in the south with Arabian Sea on the west and Kodagu hills on the eastern boundary.[25]

Nannan of Ezhil mala was the most celebrated ruler of this dynasty. Surviving Tamil anthologies draw a brilliant picture of Nannan and describe his engagements with ruling elites such as the Cheras.[24] He was more of a tribal chieftain who engaged primarily in plundering raids in the neighboring territories.[27]

However, in the beginning of the 1st century AD, the kingdom of Ezhil mala rose to political prominence under Nannan with his capital at Pazhi. Nannan was a warrior king who conducted expeditions deep into the interior regions and brought the Wynad-Gudalur region and a part of Kongunadu (Salem-Coimbatore region) under his control. According to Tamil poets he made several victories (including the Battle of Pazhi) over the Cheras. King Narmudi Cheral, the successor of Sel Kelu Kuttuvan, sent Chera forces under General Migili against Nannan. But, he was defeated in the Battle of Pazhi against the Ezhil mala forces. But later, Nannan was defeated in a series of subsequent engagements. He was forcesd to flee his capital Pazhi and seek asylum in Wynad hills. The battles ended when Narmudi Cheral crushed Nannan's forces in the Battle of Vagai Perum Turai. According to Agananuru, Nannan was killed in the battle. After his death, the control of the Ezhimala kingdom came under the Cheras.

The city of Pazhi, the later capital of the Ezhil mala kingdom, was famous for its rich treasures of gold and precious stones. They had close trade relations with the ancient Romans on Malabar Coast.

North Malabar was a hub of Indian Ocean trade during this era. According to Kerala Muslim tradition, Kolathunadu was home to several of the oldest mosques in the Indian subcontinent. According to the Legend of Cheraman Perumals, the first Indian mosque was built in 624 AD at Kodungallur with the mandate of the last ruler (the Cheraman Perumal) of Chera dynasty, who left from Dharmadom to Mecca and converted to Islam during the lifetime of Muhammad (c. 570–632).[28][29][30][31]

According to Qissat Shakarwati Farmad, the Masjids at Kodungallur, Kollam, Madayi, Barkur, mMangalore, Kasaragod, Kannur, Dharmadam, Panthalayani, and Chaliyam, were built during the era of Malik Dinar, and they are among the oldest Masjids in Indian Subcontinent.[32] It is believed that Malik Dinar died at Thalangara in Kasaragod.[33]

Most of them [clarification needed] lie in the erstwhile region of Ezhimala. The Koyilandy Jumu'ah Mosque contains an Old Malayalam inscription written in a mixture of Vatteluttu and Grantha scripts which dates back to the 10th century CE.[34] It is a rare surviving document recording patronage by a Hindu king (Bhaskara Ravi) to the Muslims of Kerala.[34]

Mushaka dynasty

[edit]

By the 8th century, the political atmosphere in southern India had changed rather dramatically as a new political culture based on settled agrarian exploitation took root in the region. As in other parts of the Indian sub-continent, Brahmanism provided the ideological support for these newly emerging regional, primarily agrarian states. An Old Malayalam inscription (Ramanthali inscriptions), dated to 1075 CE, mentioning king Kunda Alupa, the ruler of Alupa dynasty of Mangalore, can be found at Ezhimala (the former headquarters of Mushika dynasty) near Cannanore, Kerala.[35] The Arabic inscription on a copper slab within the Madayi Mosque in Kannur records its foundation year as 1124 CE.[36] The Mushika-vamsha Mahakavya, written by Athula in the 11th century, throws light on the recorded past of the Mushika Royal Family up until that point.[2]

Between the 9th and 12th centuries, a dynasty called "Mushaka" controlled the Chirakkal areas of northern Malabar (the Wynad-Tellichery area was part of the second Chera kingdom). The Mushakas were probably the descendants of the ancient royal family of Nannan of Ezhi mala and were perhaps a vassal of the Cheras. Some scholars have expressed the view that Mushakas were not under the Cheras, since the ruler of Mushaka does not figure along with the rulers of Eralnadu and Valluvanadu as a signatory in the famous Terisappalli and Jewish Copper Plates. Up to the 11th century, the Mushaka kings followed patrilineal system of succession, and thereafter they gradually switched over to the matrilineal system. In his book on travels (Il Milione), Marco Polo recounts his visit to the area in the mid 1290s. Other visitors included Faxian, the Buddhist pilgrim and Ibn Batuta, writer and historian of Tangiers.

Mushika-vamsha, a Sanskrit poem written by Atula, describes a number of Mushaka kings such as Vikrama Rama, Jayamani, Vallabha II and Srikantha. Atula was the court poet of King Srikantha who ruled towards the end of the 11th century AD.

King Vikrama Rama is said to have saved the famous Buddhist vihara of Sri Mulavasa from a terrible sea erosion on the Malabar Coast. Prince Vallabha II was dispatched by King Jayamani to assist the Chera forces during the invasion of the Chola ruler Kulottunga. However, before he could join with the Chera army, he heard the death of his father and he returned to the capital to prevent the usurpation of the Mushaka throne by his enemies. On reaching the capital, he defeated his rivals and ascended the throne. Vallabha II also founded the port of Marahi (Madayi) at the mouth of Killa river and the port of Valabha Pattanam (Valiaptam). The city of Valabha Pattanam was protected with lofty towers and high walls. He also annexed Laccadive, Minicoy and Amindivi islands in the Arabian sea. Srikantha (also known as Raja Dharma), his younger brother, succeeded Vallabha II.

According to the Mushika Vamsa, Rama Ghata Mushaka established the lineage of Kola Swarupam.[37] In addition, an inscription dating to 929 AD mentions about one Vikrama Rama, identifiable with the ruler Vikrama Rama who appears in the Mushika Vamsa.[38] Another inscription from 10th century AD mentions a chieftain, Udaya Varma, who bore the title "Rama Ghata Muvar"— an epithet used by the Mushaka kings. An inscription from the Tiruvattur temple mentions an Eraman Chemani (Rama Jayamani) who is identifiable with the king who appears as the 109th ruler in the Mushika Vamsa.[39]

They intermarried very frequently with the Cheras, the Pandyas and the Cholas, and also might have given rise to the royalties of the Lakshadweep and the Maldives.[40][41] The Mushaka family has found mention in surviving mythical Indian texts like the Vishnu Purana[42] and also in Greek accounts like that of Strabo.[43] The Kolathiris are praised as Vadakkan Perumals ("Kings of the North") by the noted "Keralolpathi".[44]

Rise of Kolathunadu (Cannanore)

[edit]

The socio-cultural uniqueness of the state called Kolathunadu became more distinctive only after the disappearance of the Second Cheras by the early 12th century.[22] The Indian anthropologist Ayinapalli Aiyappan states that a powerful and warlike clan of the Bunt community of Tulu Nadu was called Kola Bari and the Kolathiri Raja of Kolathunadu was a descendant of this clan.[5] Before the arrival the Portuguese, Calicut fought a number of wars against Cannanore (Kolathunad). A prince of the Kolattiri royal family was stationed at Pantalayini Kollam as southern Viceroy. Pantalayini Kollam was an important port on the Malabar Coast. During his conquests, the Zamorin occupied Pantalayini Kollam as a preliminary advance to Cannanore. Kolattiri immediately sent ambassadors to submit to whatever terms Calicut might dictate. Cannanore officially transferred the regions already occupied to Calicut and certain Hindu temple rights.

Foreign accounts also corroborate the distinct identity of Kolathunadu. Marco Polo, who visited Malabar coast in the 12th century, noticed the independent status of the king of this region.[45] The 14th century narrative of Ibn Battuta refers to the ruler of this region as residing at a city called Balia Patanam.[46] This offers a clue that by this time, the capital of Kolathunadu had shifted from Ezhil mala to Balia Patanam, a town located south of Ezhil mala. In the 16th century, a Portuguese official Duarte Barbosa also mentions Balia Patanam ("Balia Patam" in European records) as the residence of the king of Cannanore.[9]

Until the 16th century CE, Kasargod town was known by the name Kanhirakode (may be by the meaning, 'The land of Kanhira Trees') in Malayalam.[47] The Kumbla dynasty, who swayed over the land of southern Tulu Nadu wedged between Chandragiri River and Netravati River (including present-day Taluks of Manjeshwar and Kasaragod) from Maipady Palace at Kumbla, had also been vassals to the Kolathunadu kingdom of North Malabar, before the Carnatic conquests of Vijayanagara Empire.[48] The Kumbla dynasty had a mixed lineage of Malayali Nairs and Tuluva Brahmins.[49] They also claimed their origin from Cheraman Perumals of Kerala.[49] Francis Buchanan-Hamilton states that the customs of Kumbla dynasty were similar to those of the contemporary Malayali kings, though Kumbla was considered as the southernmost region of Tulu Nadu.[49] During the 17th century, Kannur was the capital city of the only Muslim Sultanate in the Malabar region - Arakkal - who also ruled the Laccadive Islands in addition to the city of Kannur.[50]

The port at Kozhikode held the superior economic and political position in medieval Kerala coast, while Kannur, Kollam, and Kochi, were commercially important secondary ports, where the traders from various parts of the world would gather.[51] The Portuguese arrived at Kappad Kozhikode in 1498 during the Age of Discovery, thus opening a direct sea route from Europe to India.[52] The St. Angelo Fort at Kannur was built in 1505 by Dom Francisco de Almeida, the first Portuguese Viceroy of India.

Administration

[edit]

The political lordship of the original kingdom of Kolattiri was partitioned along various matrilineal-divisions of the Kolattiri family and had rulers of the respective parts or Kũrvāzhcha (part-dominions) namely Kolattiri, Tekkālankũr, Vadakkālankũr, Naalāmkũr, and Anjāmkũr. The administration of Kolattunādu was divided into various segments of authority each of which performed functions similar to those of the superior powers but on a smaller scale.[53]

The administration was conducted through chiefs-in-tenant under the Kolattiri. This included dignitaries called "nāduvazhis", "desavazhis" and "mukhyastans". The nāduvazhis, who were heads of "nādus" or districts headed Nair militias of 500 -20,000. Below the nāduvazhis in the administrative hierarchy were desavazhis who were heads of hamlets called "desams". These were divisions of nādus. Desavazhis headed Nair militias ranging from 100 to 500 men. Below the desavazhis were other local potentates called mukhyastans. However, as in any feudal society, the Kolattiris were unable to centralize their state and the inability of the Kolattiris to monopolize the use of force in the realm on account of their weak economic position meant that the outward appearance of regal authority remained more or less nominal.

Decentralized realm

[edit]There appears to have been a significant discrepancy between the ideal type of polity presented in Brahmanical texts such as the Keralolpathi, where the Kolathiri Rājā is presented as the custodian of legitimized political power, and the actual working of power relations in the region.

It appears the Kolathiris never exercised a monopoly of authority in the realm. Authority was a decentralized, shared, and pluralistic entity. The kingly status attributed to the Kolathiris remained more or less a nominal one. The Kolathiris had to sustain their political dignity within the constraints set by the limits of their economic resource base as the geographical features of Kolathunādu did not guarantee a large-scale agricultural surplus. Shaped by the limited agrarian economy in Kolathunādu, the possibility of a centralized political structure to emerge was limited.[54]

This constricted opportunity to exploit the limited agricultural surplus obviously restricted the chances of the Kolathiris to exercise considerable influence over the people of the region. Instead, there emerged a fluctuating field of powerful taravādus of Nāyars exercising control over the resources from their respective landed properties and the dependent labour-service classes. The inability of the Kolathiris to monopolize the use of force in the realm on account of their weak economic position meant that the outward appearance of regal authority remained more or less nominal.

The Kolathiri Dominion emerged into independent 10 principalities i.e., Kadathanadu (Vadakara), Randathara or Poyanad (Dharmadom), Kottayam (Thalassery), Nileshwaram, Iruvazhinadu (Panoor, Kurumbranad etc., under separate royal chieftains due to the outcome of internal dissensions. The Poyanad (Randu Thara) and a vast area of land including (Anjarakkandy, Chembilod, Mavilayi, Edakkad, and Dharmadam) up to New Mahe was ruled by achanmaar of Randuthara. Randuthara Achanmār is a conglomerate of 4 Nambiār families (Kandoth, Palliyath, Āyilliath and Arayath) who were descendants of Edathil Kadāngodan and Ponnattil Māvila and were chieftains of Poyanādu. The "Achanmar's" later came under the special care of the English East India Company. [55]

The Nileshwaram dynasty on the northernmost part of Kolathiri dominion, were relatives to both Kolathunadu as well as the Zamorin of Calicut, in the early medieval period.[56]

Events leading to British colonization and after

[edit]

Important events between 1689 and 2000 leading to British colonization of Kolathunādu.[57]

1689: Kolattiri Rājā and his prince regent (Vadakkālankũr), to protect the latter from his adversary Kurangoth nāyar, sent an ultimatum to the then British interlopers in Malabar to let them know that they could continue to trade in north Malabar only if they agreed to build a factory in the area.

1708: Completion of Thalassery fort.

1722 : The French claim for a factory was staked at Māhe to protect their interest in Malabar. They started to wage a war against the Vāzhunor of Badagara with a view to establishing a factory in Māhe which was only three miles south of Thalassery. Kolattiri through a royal writing granted to the East India Company ’all the trades and farms’ within his ’territory from Canharotte down the Pudupatnam river’, excluding the areas where concessions were held by the Dutch who were based at Kannũr. The British were also authorized to ’punish, prevent and driveaway’ ’any other stranger’ who interfered with their concessions.

1725: French established factory at Māhe by making a deal with Vāzhunor.

1720s Ali Raja of Arackal Raja attacked the then Prince Regent of Kolathunād, Cunhi Homo and he approaches the British for succour in return for the privileges and factory granted to them by his uncle the Kolathiri.

August 1727 : Chief of Thalassery informs the Prince Regent that it is the policy of the Bombay Presidency to supply local potentates with ammunition to wage wars at their own expense.

1728 Chief of Thalassery, Adams, was recalled to Bombay and Prince regent asks for military assistance from Dutch at Cochin. The Dutch demanded the port of Dharmapatanam in return. The East India Company fearing Dutch influence supplied Kolathunād with 20,000 fanams of military stores and Ali Rājā was silenced. The British in return were given exclusive permission over other Europeans to buy spices in Kolathunādu by Prince Udaya Varman.

1732-34: Kanarese invaded North Malabar in 1732 at the invitation of the Arackal Raja. Under the command of Gopalaji, 30,000 strong Kanarese soldiers, easily overran Cunhi Homo's forts in northern Kolathunād. Early in 1734 the Kanarese soldiers captured Kudali and Dharmapatanam

1736: Kanarese army was driven out of the whole of North with assistance from the British but the Prince Regent incurs a huge debt with the factors at Tellichery as a result 1737: Nayaks of Bednur plan another attack on Kolathunādu. Prince Cunhi Homo agreed to sign a peace treaty with the Kanarese which fixed the northern border of Kolathunād on the Madday. The factors of Tellicherry also signed their own treaty with the Nayak of Bedanur which guaranteed the integrity of British trading concessions in Malabar in the event of future conflicts between the Kanarese and the rulers of Kolathunād.

1739-42 Prince Ockoo, a French supported adversary of the Prince regent and his followers were killed by the factors of Tellichery.

1741 Prince regent asked his vassals, the Achanmārs of Randuthara to contribute 30,000 fanams towards defraying state debt. The Achanmārs refused. Prince Regent's threatened to assume the collection of tribute in Randuthara unless the Achanmārs agreed. the British arranged to pay the Prince Regent the sum of 30,000 fanams on behalf of the Achanmārs in exchange for the land revenue collection of Randuthara. Thus the debt trap was an important instrument which the British used to secure the monopoly of trade in Malabar.

1745: The direct relations which the factors of Tellicherry were cultivating with the vassals of Kolathunād, however, tended to alienate the Kolattiri. The Prince Regent of Kolathunād accused the factors of Tellicherry of interfering ’too much in the government of his country’.

1746: Death of Prince Udaya Varman. The disintegration of the Kolathiri's dominion had started and the English fanned dissensions in the royal family. The British started taking control of more and more area by purchasing land through consorts of the royal family.

October 1747: Minor war between Kolathiri and factors at Tellichery who using Prince Raman Unithiri ’chastized’ ’ant-British ministers’ in the samastanom. On succession due to Prince Kunhi Homos death, Prince Cunhi Raman tried to ambition to reaffirm his authority upon his Vassals to the East India Company concern. Having consolidated his authority, Prince Cunhi Raman embarked on a policy of centralizing the administration of Kolathunād so as to acquire more power over his vassals. He expressed the desire to collect the land revenue of Randuthara because he felt that the Achanmār no longer obeyed him.

1749: Prince Cunhi Raman threatened to appoint his own sons to administer the taluks of Iruvalinad and Kadattanad. In the same year, however, the Boyanore cut the last links of Vassalage with the Kolathunād palace and declared himself Rājā of Kadattanad. The Nambiārs of Iruvalinād threatened to follow suit. The Achanmār of Randuthara appealed to the British for more protection. Kolathunād was being dismembered. The Kolattiri and his Prince Regent were being forced to withdraw to Kolathunād ’proper’ and so restrict their authority to what was to become the taluk of Chirakkal.

April 1751: Following the Boyanore's assumption of the title of Rājā, Prince Cunhi Raman declared war on Kadattanad, Iruvalinad where the East India Company had acquired the monopoly of buying pepper. Following many discussions, the factors managed to convince the Kolattiri (the Senior Rājā of Kolathunād) to dismiss Prince Kunhi Raman and appointed Ambu Tamban as Prince Regent in the presence of Thomas Derryl of the East India Company at Thalassery.

October 1751: Prince Cunhi Raman allowed the French to fortify Mount Delli so as to disrupt the British rice trade between Mangalore and Tellicherry.

January 1752: The Rājā of Cotiote mediated for a settlement between Tellicherry and Kolathunād.

1756: Death of Prince Cunhi Raman and succession by Prince Rama Varma.

1760: Death of Prince Rama Varma

August 1760: Unanamen Tamban (new Prince Regent) had Siben Putteiah, the leader of the pro-British faction in the Kolathunād Raj, blinded.

1761: Kolattiri dismisses the Prince Regent and took charge of the Kolathunād Raj directly and granted the British the right to collect all the custom duties of North Malabar on behalf of the samastanom. In 1761, the British captured Mahé, and the settlement was handed over to the ruler of Kadathanadu.[58]

1763:The British restored Mahé to the French as a part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[58]

1764: Prince of Chirakkal took over the administration of Kolathunād.

1765: Prince of Chirakkal recognized the dominant position of Tellicherry in the taluk of Randuthara by ceding the area to the East India Company.

Feb 1766: Hyder Ali along with a formidable force is welcomed into Kerala by the Ali Rājā of Kannũr. The Mysorean army guided by Ali Rājā and his brother seize the palace of the Rājā of Kolathiri at Chirakkal. The Rājā and his family flee south to take refuge at the English trading station in Thalassery. He appointed Ali Rājā as his Naval Chief (High Admiral) and the Rājā 's brother Sheik Ali as Chief of Port Authority (Intendant of Marine).

1773: Hyder Ali invaded Malabar for a second time in 1773 on the pretext that the Rajas of Malabar had not paid him tribute as agreed in 1768.[59]

1779: In 1779, the Anglo-French war broke out, resulting in the French loss of Mahé.[58]

1783: In 1783, the British agreed to restore to the French their settlements in India.

1785: Mahé was handed over to the French in 1785.[58]

Feb 1789: Tipu Sultan enters Malabar for the second time as all the Rājā and Chieftains of North Malabar had revolted and declared their independence from Mysore. He devastated Kadathanād and marries off his son (Abdul Khalic) to the daughter of the Arackal Bibi of Kannũr. One of the princes of the Kolathiri family was killed by Tippu's soldiers during his escape and his dead body was dragged by elephants through Tippu's camp and it was subsequently hung up on a tree along with seventeen of his followers who had been captured alive.

May 1790: Tipu leaves Malabar never to return

March 1792: Malabar was formally ceded to the British. The British entered into agreements with the Rājā of Chirakkal, Kottayam and Kadathanād and all of them acknowledged the full sovereignty of the Company over their respective territories. The British Government divided the province of Malabar into two administrative divisions - the Southern and Southern, presided over by a superintendent each at Thalassery and Cherpulasseri, under the general control of the supervisor and chief magistrate of the province of Malabar who had his headquarters at Calicut.

1800: Malabar was made a part of the Madras Presidency

1801: Death of the last Kolathiri Rājā who ceded all his dominions to the British (was commonly known as the first Rājā of Chirakkal). Major Macleod took charge as the first principal collector of Malabar on 1 October 1801.

Kolathunād remained part of Malabar District (an administrative district of British India under Madras presidency till 1947 and later part of India's Madras State till 1956. On 1 November 1956, the state of Kerala was formed by the States Reorganisation Act merging the Malabar district, Travancore-Cochin (excluding four southern taluks, which were merged with Madras State.

Constitution of the Kolathiri family

[edit]By the 17th century, the Kolaswarũpam had to share its political authority with two other lineages in north Kerala. The Nileswaram (Alladam) Swarũpam and the Arackal Swarũpam claimed independent political identity. Moreover, political power within the Kolaswarũpam was also disseminated into different kovilakams. In the Keralolpathi there are four kovilakams sharing the political authority of the Kolaswarupam namely: Talora Kovilakam; Arathil Kovilakam; Muttathil Kovilakam; Karipathu Kovilakam; and Kolath Kovilakam.[60] According to the Keralolpathi Kolathunādu tradition, the Karipathu Kovilakam and Kolath Kovilakam claimed some sort of superiority over the others. However, it was the Palli Kovilakam and the Udayamangalam Kovilakam, as apparent from the Dutch records, which dominated the political scene of Kolathunadu Both these kovilakams had again branched into various kovilakams, thereby, creating a network of political houses within the Kolaswarupam.

The original kingdom of Kolathiri was partitioned along 5 matrilineal-divisions of the Kolathiri family and had rulers of the respective parts/ Kũr-Vāzhcha (part-dominions) namely Kolattiri, Tekkālankũr, Vadakkālankũr, Naalāmkũr, Anjāmkũr.

| The matrilinial divisions of the Kolathiri family (Kovilakams)[61] | |||

| Division | Branch | Sub-branch | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Udayamangalam | |||

| Palli | Chirakkal | ||

| Chenga | Prāyikkara at Māvelikkara, Ennakkāt' (Further divided into Ennakkāt and Māvelikkara) | ||

| Tevanam Kotta | |||

| Padinjāre | |||

| Thekumkure | Kolath kovilakam | ||

| Kāvinishery | |||

During the period of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan from 1766 to 1792 multiple military invasions, plunder and systematic forcible conversions were performed in North and South Malabar alike.[59][62][63] Fearing forcible conversion, a significantly large section (Chieftains and Brahmins) of the 'Malabar' region, including the Kolathiri, fled with the material wealth of the temples in their dominions, to take refuge in the erstwhile kingdom of Travancore. Travancore had an alliance (Treaty of Mangalore) with the English Company according to which "an aggression against Travancore would be viewed as equivalent to declaration of war against the English". Thus at various time points between 1766 and 1792, all female members and many male members of Kolathiri family along with their temples' wealth, had taken refuge in Thiruvananthapuram. On the restoration of peace in Malabar, while the family went back, three sisters stayed back in Travancore at Mavelikkara. Dissensions resulted in one of them moving to Ennakkad while another settled at Prayikkara and other group settled in Kozhanchery. Thus three matrilinial branches of the Kolathiri family settled in Travancore and established the royal houses of Mavelikkara, Kozhanchery, Ennakkat and Prayikkara.

Supersession of the title Kolathiri Rājā

[edit]Earlier members of both Udayamangalam and Palli divisions were eligible to assume the title of Kolathiri Rājā based on their seniority in age. The invasion of the domains of Kolathiri family by Rājā of Bednũr / Ikkeri and subsequent settlement between Kolathiri and the invader in AD 1736-37 led to considerable change within the family of Kolathiris. The Udayamangalam branch was shut out from assuming the title Rājā and the title of Kolathiri fell into disuse. The ruling family (Palli division) monopolized the right of succession as Rāja, leading to the supersession of the ancient title of Kolathiri Rājā to the Chirakkal Raja.[64][61]

Ascension to Kshatriyahood

[edit]In 1617 A.D Kolathiri Rāja, Udayavarman, wished to further promote himself to full recognition by performing Hiranya-garbhā, which the Nambũdiris refused. As he attempted to force the Nambũdiri Brahmins of Taliparamba (Perumchellũr) to perform this ritual for him, the Nambũdiri Brahmins refused him by stating:

‘Kolathiri had no right to ask them to perform a sacrifice since in the jurisdiction of Perumtrikkovilappan (the deity of the Rajarajeswara temple of Perumchellũr, Taliparamba) the order of any king would not be valid’ (The epithet of the deity rajarajeswara or king of the kings blatantly indicates the royal status assumed by the deity).[14] As Historian Samuel Mateer; "There seems reason to believe that the whole of the kings of Malabar also, notwithstanding the pretensions set up for them of late by their dependents, belong to the same great body, and are homogeneous with the mass of the people called Nairs, So Namboodiris were reluctant to give Kshtriyahood to all the Nair lords, Consequently, Udayavarman brought 237 Brahmin families (Sāgara Dwijas) from Gokarnam and settled them in five Desams. (Cheruthāzham, Kunniriyam, Arathil, Kulappuram and Vararuchimangalam of Perinchelloor Grāmam). The latter adopted Nambũdiri customs and performed Hiranya-garbhā and conferred Kshatriyahood on the former. Later, on the request of Rājā of Travancore, 185 of these Sāgara dwijans families were sent to Thiruvalla. (Thiruvalladesi Embraanthiris).[13]

Calendar system

[edit]The version of Kolla-Varsham or Kolla-varsham practiced in central/south Kerala excepting North Malabar (Kolathunadu) began on 25 August 825 A. D and the year commences with Simha-raasi (Leo) and not in Mesha-raasi (Aries) as in other Indian calendars. Although there are several accounts, current, recorded and hearsay about the commencement of the Kollam era, however in erstwhile North Malabar / Kolathunadu, the Kollam era is reckoned from the next month, Kanya-rasi (Virgo) (25 September) instead. This variation has two interesting accounts associated with it.[65]

(1) The traditional text Kerololpathi attributes the introduction of Kollam era to Shankaracharya. So if you convert the word "Aa chaa rya vaa ga bhed ya" (meaning Shankaracharya's word/law is unalterable) into numbers in the Katapayadi notation it translates into 0 6 1 4 3 4 1 and these written backwards gives the age of the Kali Yuga on the first year of the Kollam era. Kali day 1434160 would work out to be 25 September 825 A.D which corresponds to the beginning of Kollam era in Kolathunadu, i.e. the first day of the Kanya-raasi (Virgo).

(2) The second account is that Kollam era commenced with the proclamation made at Kollam.

Royal symbols of Kolathiri

[edit]According to legend, Lord Parasurama is said to have provided Ramaghatha Mooshikan on his day of coronation (1) Naandakam Vaal (a special sword) (2) and assigned the herb Nenmeni-vaka (Mumosa lebbek) as the tree associated with the dynasty (3) and further assigned Vaakapookkula (infloresense of Mumosa lebbek) and Changalavattam Vilakku (This is a heavy bronze lamp used in temple processions and the lamp itself has an oil storage space with a spoon attached to it by chain), as the royal symbols. The Kola-swaroopam dynasty believes that it is this association of theirs with Nenmeni-vaka (Mumosa lebbek) that led to their nomenclature as Mooshikan. The Royal flag and the Royal seal of the Kolathiri family therefore was a combination of images namely : Thoni (a boat), Changalavattam Vilakku, Naandakam Vaal and Nenmeni-vaka.

Royal flag/standard (Kodikkoora or dwajam)

[edit]The imagery of the flag consisted of two Naandakam-Vaal-swords on either sides with a centrally placed Vaakapookkula-infloresense of Mumosa lebbek and five half crescents beneath.

Royal seal (Mudra)

[edit]The imagery of the seal consisted of a thoni-boat beneath, a changalavattam-lamp above it, further above a vertically placed Naandakam-vaal-sword, followed on either adjacent sides by a Vaakapookkula-infloresense each.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Keralolpatti Granthavari: The Kolattunad Traditions (Malayalam) (Kozhikode: Calicut University, 1984) M. R. Raghava Varier (ed.)

- ^ a b c Sreedhara Menon, A. (2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. p. 175. ISBN 978-8126415885. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Sreedhara Menon, A. (4 March 2011). Kerala History and its Makers. D C Books. ISBN 9788126437825.

- ^ Perumal of Kerala by M. G. S. Narayanan (Kozhikode: Private Circulation, 1996)

- ^ a b Ayinapalli, Aiyappan (1982). The Personality of Kerala. Department of Publications, University of Kerala. p. 162. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

A very powerful and warlike section of the Bants of Tulunad was known as Kola bari. It is reasonable to suggest that the Kola dynasty was part of the Kola lineages of Tulunad.

- ^ Singh, Anjana (2010). Fort Cochin in Kerala, 1750-1830: The Social Condition of a Dutch Community in an Indian Milieu. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004168169.

- ^ Induchudan, V. T. (1971). The Golden Tower: A Historical Study of the Tirukkulasekharapuram and Other Temples. Cochin Devaswom Board. p. 164.

- ^ de Lannoy, Mark (1997). The Kulasekhara Perumals of Travancore: History and State Formation in Travancore from 1671 to 1758. Leiden University. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-73782-92-1.

- ^ a b Duarte Barbosa, The Book of Duarte Barbosa: An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and their Inhabitants, II, ed. M. L Dames (repr., London: Hakluyt Society, 1921)

- ^ The Dutch in Malabar: Selection from the Records of the Madras Government, No. 13 (Madras: Printed by the Superintendent, Government Press, 1911), 143.

- ^ British Indian Government of Madras (1891). Malabar Marriage Commission Report.

- ^ Mateer, Samuel (1883). Native Life in Travancore. W.H. Allen & Company.

- ^ a b c Namboothiri Websites Kozhikode. "The Saagara Dwijans of Kerala". Namboothiri.com. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ a b Srauta Sacrifices in Kerala (Kozhikode: Calicut University, 2002), 98 by V. Govindan Namboodiri;Freeman, ‘Purity and Violence’, 527-8

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- ^ Gurukkal, R., & Whittaker, D. (2001). In search of Muziris. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 334-350.

- ^ A. Shreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History

- ^ According to Pliny the Elder, goods from India were sold in the Empire at 100 times their original purchase price. See [1]

- ^ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ^ Das, Santosh Kumar (2006). The Economic History of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ a b Narayanan, Re-Interpretations in South Indian History, 6-10

- ^ Foundations of South Indian Society and Culture by M. G. S. Narayanan, (Delhi: Bharatiya Book Corporation, 1994), 194

- ^ a b Kolathupazhama by Kumaran

- ^ a b District Census Handbook, Kasaragod (2011) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Directorate of Census Operation, Kerala. p. 9.

- ^ a b Government of India (2014–15). District Census Handbook – Wayanad (Part-B) 2011 (PDF). Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala.

- ^ Rajan Gurukkal, ‘Antecedent of the State Formation in South India’, in R. Champakalakshmi, Kesavan Veluthat, T. R. Venugopalan, (eds.), State and Society in Pre-modern South India (Trissur: Cosmobooks, 2002), pp. 39-59

- ^ Jonathan Goldstein (1999). The Jews of China. M. E. Sharpe. p. 123. ISBN 9780765601049.

- ^ Edward Simpson; Kai Kresse (2008). Struggling with History: Islam and Cosmopolitanism in the Western Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-231-70024-5. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Uri M. Kupferschmidt (1987). The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine. Brill. pp. 458–459. ISBN 978-90-04-07929-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Husain Raṇṭattāṇi (2007). Mappila Muslims: A Study on Society and Anti Colonial Struggles. Other Books. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-81-903887-8-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018. Pg. 98.

- ^ Pg 58, Cultural heritage of Kerala: an introduction, A. Sreedhara Menon, East-West Publications, 1978

- ^ a b Aiyer, K. V. Subrahmanya (ed.), South Indian Inscriptions. VIII, no. 162, Madras: Govt of India, Central Publication Branch, Calcutta, 1932. p. 69.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 483.

- ^ Charles Alexander Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I). Madras Government Press. pp. 423–424.

- ^ Mushikavamsam. Raghavan Pilla (ed.), Mushikavamsam, 26, 268

- ^ Kerala Charithrathinte Adisthana Silakal (Malayalam) by M. G. S. Narayanan, (Kozhikode: Lipi Publications, 2000), 85-99

- ^ A History of Mushikavamsa by N. P. Unni, (Trivandrum: College Book House, 1978), 14

- ^ "Content". Organiser. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ V.Jayaram. "Traces of the Mahabharat in Sangam Literature". Hinduwebsite.com. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman (April 2009). The Vishnu Purana - Google Books. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9780559054679. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Age of the Nandas and Mauryas - Google Books. Motilal Banarsidass. 1988. ISBN 9788120804661. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Varier, Keralolpatti Granthavari, 51

- ^ The Book of Ser Marco Polo: The Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, III, 3rd edn. ed. Henry Yule and Henri Cordier (repr., Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1975), 385

- ^ The Rehla of Ibn Battuta (India, Maldive Islands and Ceylon), tr. and commentary by Mahdi Husain (Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1953), 186

- ^ S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- ^ M. Vijayanunni. 1981 Census Handbook- Kasaragod District (PDF). Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala.

- ^ a b c Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 978-81-264-1588-5. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "Arakkal royal family". Archived from the original on 5 June 2012.

- ^ The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500–1800. Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K. S. Mathew (2001). Edited by: Pius Malekandathil and T. Jamal Mohammed. Fundacoa Oriente. Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR (Kerala)

- ^ DC Books, Kottayam (2007), A. Sreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History

- ^ Lectures on Enthurdogy by A. Krishna Ayer Calcutta, 1925.

- ^ Female Initiation Rites on the Malabar Coast, Gough, Kathleen 1955a, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- ^ Logan, William (2010). Malabar Manual (Volume-I). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 631–666. ISBN 9788120604476.

- ^ The Hindu staff reporter (21 November 2011). "Neeleswaram fete to showcase its heritage". The Hindu. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ B. Swai (1985). "From Kolattunad to Chirakkal: British Merchant Capital and the Hinterland of Tellicherry, 1694–1766". Studies in History. 1: 87–110. doi:10.1177/025764308500100107. S2CID 161182476.

- ^ a b c d "History of Mahé". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ a b Malabar Manual by William Logan (Printed and published by Charitram Publications under the editorship of Dr. C.K, Kareem, Trivandrum)

- ^ Varier, Keralolpatti Granthavari, 52-3

- ^ a b Establishment of British power in Malabar, 1664 to 1799 By N. Rajendran

- ^ Voyage to East Indies by Fra Bartolomaeo (Portuguese Traveller and Historian)

- ^ Historical Sketches by Col. Wilks, Vol. II.

- ^ Kerala District Gazetteers: Cannanore (1962)

- ^ K.V Sarma (1996), Kollam era, Indian Journal of History of Science, 31 (1)[2] Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch