Icelandic literature

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iceland |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Icelandic literature refers to literature written in Iceland or by Icelandic people. It is best known for the sagas written in medieval times, starting in the 13th century. As Icelandic and Old Norse are almost the same, and because Icelandic works constitute most of Old Norse literature, Old Norse literature is often wrongly considered a subset of Icelandic literature. However, works by Norwegians are present in the standard reader Sýnisbók íslenzkra bókmennta til miðrar átjándu aldar, compiled by Sigurður Nordal on the grounds that the language was the same.

Early Icelandic literature

[edit]The medieval Icelandic literature is usually divided into three parts:

The Eddas

[edit]There has been some discussion on the probable etymology of the term "Edda"[citation needed]. Most say it stems from the Old Norse term edda, which means great-grandmother, but some see a reference to Oddi, a place where Snorri Sturluson (the writer of the Prose Edda) was brought up.

The Elder Edda or Poetic Edda (originally attributed to Sæmundr fróði, although this is now rejected by modern scholars) is a collection of Old Norse poems and stories originated in the late 10th century.

Although these poems and stories probably come from the Scandinavian mainland, they were first written down in the 13th century in Iceland. The first and original manuscript of the Poetic Edda is the Codex Regius, found in southern Iceland in 1643 by Brynjólfur Sveinsson, Bishop of Skálholt.

The Younger Edda or Prose Edda was written by Snorri Sturluson, and it is the main source of modern understanding of Norse mythology and also of some features of medieval Icelandic poetics, as it contains many mythological stories and also several kennings. In fact, its main purpose was to use it as a manual of poetics for the Icelandic skalds.

Skaldic poetry

[edit]Skaldic poetry mainly differs from Eddaic poetry by the fact that skaldic poetry was composed by well-known skalds, the Norwegian and Icelandic poets. Instead of talking about mythological events or telling mythological stories, skaldic poetry was usually sung to honour nobles and kings, commemorate or satirise important or any current events (e.g. a battle won by their lord, a political event in town etc.). In narratives, poems were usually used to pause the story and more closely examine an experience occurring. Poetry was also used to dramatise the emotions in a saga. For example, Egil's Saga contains a poem about the loss of Egil's sons that is lyrical and very emotional.

Skaldic poets were highly regarded members of Icelandic society, and are typically divided into four categories: 1) Professional Poets (for the court or aristocrats) When Skaldic poets composed lyrics for the king, they wrote with the purpose of praising the king, recording his dealings, and celebrating him. These poems are generally considered historically correct[1][citation needed] because a poet would not have written something false about the king; a king would have taken that as the poet mocking him.[citation needed]

Ruling aristocratic families also appreciated poetry, and poets composed verses for important events in their lives as well.

2) Private Poets

These poets did not write for financial gain, rather, they wrote to participate in societal poetic exchanges.

3) Clerics

These poets composed religious verses.

4) Anonymous Poets

These poets are anonymously quoted and incorporated into sagas. The anonymity allowed them to mask the comments they made with their verses.[2][citation needed]

Skaldic poetry is written using a strict metric system together with many figures of speech, like the complicated kennings, favoured amongst the skalds, and also with a lot of “artistic license” concerning word order and syntax, with sentences usually inverted.

Sagas

[edit]The sagas are prose stories written in Old Norse that talk about historical aspects of the Germanic and Scandinavian world; for instance, the migration of people to Iceland, voyages of Vikings to unexplored lands, or the early history of the inhabitants of Gotland. Whereas the Eddas contain mainly mythological stories, sagas are usually realistic and deal with actual events, although there are some legendary sagas of saints, bishops, and translated romances. Sometimes mythological references are added, or a story is rendered more romantic and fantastical than as actually occurred. Sagas are the main sources for studying the history of Scandinavia between the 9th and 13th centuries.

Literature by women

[edit]Little medieval Icelandic writing is securely attested to be by women. In theory, anonymous sagas might have been written by women, but there is no evidence to support this, and known saga-writers are male.[3] A fairly large number of Skaldic verse stanzas are attributed to Icelandic and Norwegian women, including Hildr Hrólfsdóttir, Jórunn skáldmær, Gunnhildr konungamóðir, Bróka-Auðr, and Þórhildr skáldkona. However, the poetry attributed to women—just like much of the poetry attributed to men— is likely to have been composed by later (male) saga-writers. Even so, this material suggests that women may sometimes have composed verse.[4]

However, the authorial voice of the fifteenth-century rímur-cycle Landrés rímur describes itself with grammatically feminine adjectives, and accordingly the poem has been suggested to be the earliest Icelandic poem reliably attributable to a woman.[5]

Middle Icelandic literature

[edit]| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

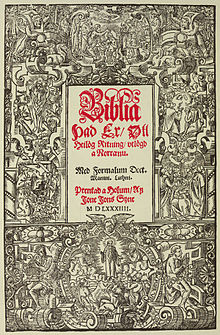

Important compositions of the time from the 15th century to the 19th include sacred verse, most famously the Passion Hymns of Hallgrímur Pétursson; rímur, rhymed epic poems with alliterative verse that consist of two to four verses per stanza, popular until the end of the 19th century; and autobiographical prose writings such as the Píslarsaga of Jón Magnússon. The first book printed in Icelandic was the New Testament in 1540. A full translation of the Bible was published in the sixteenth century, and popular religious literature, such as the Sendibréf frá einum reisandi Gyðingi í fornöld, was translated from German or Danish or composed in Icelandic. The most prominent poet of the eighteenth century was Eggert Ólafsson (1726–1768), while Jón Þorláksson á Bægisá (1744–1819) undertook several major translations, including the Paradísarmissir, a translation of John Milton's Paradise Lost. Sagas continued to be composed in the style of medieval ones, particularly romances, not least by the priest Jón Oddsson Hjaltalín (1749-1835).[6]

Modern Icelandic literature

[edit]Literary revival

[edit]In the beginning of the 19th century, there was a linguistic and literary revival. Romanticism arrived in Iceland and was dominant especially during the 1830s, in the work of poets like Bjarni Thorarensen (1786–1841) and Jónas Hallgrímsson (1807–45). Jónas Hallgrímsson, also the first writer of modern Icelandic short stories, influenced Jón Thoroddsen (1818–68), who, in 1850, published the first Icelandic novel, and so he is considered the father of the modern Icelandic novel.

This classic Icelandic style from the 19th and early 20th centuries was continued chiefly by Grímur Thomsen (1820–96), who wrote many heroic poems and Matthías Jochumsson (1835–1920), who wrote many plays that are considered the beginning of modern Icelandic drama, among many others. In short, this period was a great revival of Icelandic literature.

Realism and naturalism followed romanticism. Notable Realistic writers include the short-story writer Gestur Pálsson (1852–91), known for his satires, and the Icelandic-Canadian poet Stephan G. Stephansson (1853–1927), noted for his sensitive way of dealing with the language and for his ironic vein. Einar Benediktsson must be mentioned here as an early proponent of Neo-romanticism. He is in many ways alone in Icelandic poetry, but is generally acknowledged to be one of the great figures of the "Golden Age" in poetry.[7]

In the early 20th century several Icelandic writers started writing in Danish, among them Jóhann Sigurjónsson, and Gunnar Gunnarsson (1889–1975). Writer Halldór Laxness (1902–98), won the 1955 Nobel Prize in Literature, and was the author of many articles, essays, poems, short stories and novels. Widely translated works include the expressionist novels Independent People (1934–35) and Iceland's Bell (1943–46).

After World War I, there was a revival of the classic style, mainly in poetry, with authors such as Davíð Stefánsson and Tómas Guðmundsson, who later became the representer of traditional poetry in Iceland in the 20th century. Modern authors, from the end of World War II, tend to merge the classical style with a modernist style.

More recently, crime novelist Arnaldur Indriðason's (b. 1961) works have met with success outside of Iceland.

See also

[edit]- Icelandic Literary Prize

- List of Icelandic writers

- Nordic Council's Literature Prize

- Icelandic Christmas book flood

References

[edit]- ^ As far as it goes. A poet would not make up untrue deeds, but he would also leave out negative aspects.

- ^ Nordal, Guðrún. Tools of literacy: The role of skaldic verse in Icelandic textual culture of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

- ^ Haukur Þorgeirsson, 'Skáldkona frá 15. öld Archived 2016-04-04 at the Wayback Machine'.

- ^ Sandra Ballif Straubhaar, Old Norse Women's Poetry: The Voices of Female Skalds (Cambridge: Brewer, 2011), ISBN 9781843842712.

- ^ Haukur Þorgeirsson, 'Skáldkona frá 15. öld Archived 2016-04-04 at the Wayback Machine'.

- ^ Matthew James Driscoll, The Unwashed Children of Eve: The Production, Dissemination and Reception of Popular Literature in Post-Reformation Iceland (Enfield Lock: Hisarlik Press, 1997), pp. 6, 35.

- ^ Einar Benediktsson and Stephan G. Stephansson share, despite all differences, this certain "loner" status. They may not have influenced many other poets directly, but every poet has read them, and they are present in all relevant anthologies and are both required reading in schools.

Further reading

[edit]- Einarsson, Stefan (1957). A History of Icelandic Literature. New York: Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

[edit]- Icelandic Saga Database - Icelandic sagas in translation

- Old Norse Prose and Poetry

- Northvegr.org

- Nat.is: little but good page on Icelandic literature Archived 2006-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Electronic Gateway for Icelandic Literature (EGIL)

- Sagnanetið - digital images of Icelandic manuscripts and texts

- Icelandic Literature Information on contemporary authors

- Netútgáfan Literary works in Icelandic.

- The complete Sagas of Icelanders

- Icelandic Online Dictionary and Readings from the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center. Collection includes interactive Icelandic dictionary; bilingual readings about Iceland and Icelandic history, society, and culture; readings in Icelandic about contemporary Iceland and Icelanders; and Icelandic literature.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch