Rashidun cavalry

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: needs language and grammar cleanup by an English native speaker. (September 2024) |

| Rashidun cavalry | |

|---|---|

| Army of the marches (Jaish al‐Zaḥf Arabic: جيش الزحف) Mobile guard (Tulai'a Mutaharrika Arabic: طليعة متحركة) The Army of Sharpeners | |

| Active | 632–661 |

| Allegiance | Rashidun Caliphate |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Role | Shock troops Flanking maneuver Mounted archery Siege Expeditionary warfare Reconnaissance Raid Horse breeding |

| Provincial Headquarters (Amsar) | Medina (632–657) Kufa (657–661) Jund Hims (634–?) Jund Dimashq (?–?) Jund al-Urdunn (639–?) Basra (632–661) Jund Filastin (660–?) Fustat (641–?) Tawwaj (640-?) Mosul Haditha |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Supreme Commanders | Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas Amr ibn al-As |

| Notable Commanders | |

The Fursan unit, or the early Muslim cavalry unit, was the cavalry forces of the Rashidun army during the Muslim conquest of Syria. The division, which formed the early cavalry corps of the caliphate, was commonly nicknamed the Mobile Guard (Arabic: طليعة متحركة, Tulay'a mutaharikkah or Arabic: الحرس المتحرك, al-Haras al-Mutaharikkah) or the Marching Army ( جيش الزحف, "Jaish al‐Zaḥf"). These units were commanded by Khalid ibn al-Walid, an early caliphate cavalry commander who organized the unit into military staff – a simple beginning of what later in military history would emerge as the general staff. Khalid had collected from all the regions in which he had fought – Arabia, Iraq, Syria and Palestine.

This shock cavalry division, which was led by Khalid, played important roles in the victories of the Battle of Chains, Battle of Walaja, Battle of Ajnadayn, Battle of Firaz, Battle of Maraj-al-Debaj, Siege of Damascus, Battle of Yarmouk, Battle of Hazir and the Battle of Iron Bridge against the Byzantine and the Sassanid empires.[1] Later, the splinter of this cavalry division under Al-Qa'qa ibn Amr at-Tamimi became involved in the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah, Battle of Jalula, and the Second siege of Emesa.[1]

Later, after the Early Muslim conquests, portions of the Rashidun cavalry rebelled against the central caliphate in Kharijites revolutionary movements.[2] Historian Al-Jahiz remarked the Kharijites were feared for their cavalry charge with lances, which he claimed could break any defensive line, and almost never lost when pitted against an equal number of opponents.[2] These Kharijites sects, believed by most scholars of Islam to have been started by Hurqus ibn Zuhayr as-Sa'di, known as Dhu Khuwaishirah at-Tamimi,[3] would plague the rest of the history of the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid caliphates with endemic rebellions.

This cavalry unit almost certainly rode the purebred Arabian horse, by fact the quality breeding of horses were held so dearly by the early caliphates who integrated traditions of Islam with their military practice.[4][5][6][7] These horses were also a common breed amongst the Arab community during the 6th to 7th century.[4]

History

[edit]Muhammad's cavalry, the predecessor of the caliphate's, is recorded to have had 10,000 horsemen during the Expedition of Tabuk.[8] The Muslim cavalry units were commonly called Fursan.[8]

After the decisive victory at the Battle of Ajnadayn in 634 CE, Khalid, from his Iraqi army, which after Ajnadayn numbered about 8000 men, organised a force of 4000 horsemen, which the early historians refer to as The Army of Sharpeners.[9][page needed][10] Khalid kept this force under his personal command. Aside from horses for use in attacks, the Rashidun cavalry also rode camels for transportation and in defensive battles, as camels could repel even heavy cavalry such as Byzantine and Sassanid cataphracts, and are large enough to withstand a heavy cavalry's charge.[11] At the onset of the battle of Yarmuk in 636 AD, around 3,000 cavalry reinforcements were sent to the Syrian front, including those from Yemen led by Qays ibn Makshuh.[12]

Mahmud Shakir said the cavalry corps called al-Haras al-Mutaharikkah, had a distinguishing role in the battle of Yarmuk.[13] The first recorded use of this mounted force was during the Siege of Damascus (634). During the battle of Yarmuk Khalid ibn Walid used them to his advantage at critical points in the battle. With their ability to engage and disengage, and turn back and attack again from the flank or rear, the Mobile Guard inflicted a shattering defeat of the Byzantine army. This strong mobile striking force was often used in later years as an advance guard.[9][page needed] It could rout opposing armies with its greater mobility that gave it an upper hand against any Byzantine army. One of the victories of the mobile guard was at Battle of Hazir in 637 CE under the command of Khalid, in which not a single Byzantine soldier survived.[10] The Mobile guard remained under the personal command of Khalid ibn Walid for about four years (634-638 CE) until Khalid was dismissed from army by Caliph Umar after the completion of the conquest of the Levant.

With the dismissal of Khalid, this powerful cavalry regiment was dismantled. One of its brilliant commanders Qa'qa' ibn 'Amr al-Tamimi had been sent to the Persian front in 637 CE along with reinforcements for the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, in which he played an important part. A part of it was later sent to the Persian front as reinforcements for the Muslim conquest of Persia. Many of its members died in the plague during 639-640 CE which killed approximately 25,000 Muslims in Syria. This included many sub-commanders of the mobile guard like Zirrar ibn Azwar, those who survived accompanied the army under the command of Amr ibn al-'As to conquer Egypt. After the conquest of Egypt, the Rashidun Army continued to invade and besiege Bahnasa, as the enemy were reinforced by an arrival of 50,000 according to the report of al-Maqqari.[14][15] The siege dragged for months, until Khalid ibn al Walid commanded Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, Dhiraar ibn al-Azwar and other commanders to intensify the siege and assign them to lead around 10,000 Companions of the Prophet, with 70 among them were veterans of battle of Badr.[16] They besiege the city for 4 months as Dhiraar leading 200 horsemens, while Zubayr ibn Al-Awwam lead 300 horsemen, while the other commanders such as Miqdad, Abdullah ibn Umar and Uqba ibn Amir al-Juhani leading similar number with Dhiraar with each command 200 horsemens.[16] After Bahnasa finally subdued,[16] where they camped in a village which later renamed as Qays village, in honor of Qays ibn Harith, the overall commander of these Rashidun cavalry.[17] The Byzantines and their copt allies showering the Rashidun army with arrows and stones from the city wall, As the bitter fights has rages on as casualties increases,[Notes 1] until the Rashidun overcame the defenders, as Dhiraar, the first emerge, came out from the battle with his entire body stained in blood, while confessed he has slayed about 160 Byzantine soldiers during the battle.[16] Chroniclers recorded the Rashidun army has finally breached the city gate under either Khalid ibn al-Walid or Qays ibn Harith finally managed to breach the gate and storming the city and forcing surrender to the inhabitant.[Notes 2] [Notes 3]

Later, some of the caliphate's horsemen rebelled against the caliphate under Hurqus ibn Zuhayr as-Sa'di, a Tamim tribe chieftain and veteran of the Battle of Hunayn.[21][22] Hurqus joined with another warrior tribe from Bajila,[23] led by Abd Allah ibn Wahb al-Rasibi, who participated in the early conquests of Persia under Sa'd ibn abi Waqqas.[24]

As Muslim conquests of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula progressed.[25] they also brought their breeds of horse to Africa and Spain in the form of Arabian horses, Barb horses, and to a lesser extent the Turkoman horse[26]

Unit characteristics

[edit]Cavalry were highly regarded by the military rulers of early Medina, as the early Medina Islam constitution and the Caliphates' put emphasis by giving the cavalry troopers at least two portions of war spoils and booty compared to regular soldier, while regular infantry only received a single portion.[27] The core of the caliphate's mounted division was an elite unit which early Muslim historians named Tulai'a Mutaharrika (طليعة متحركة), or the mobile guard.[1]

Initially, the nucleus of the mobile guard formed from veterans of the horsemens under Khalid ibn al-Walid during the conquest of Iraq. They consisted half of the forces brought by Khalid from Iraq to Syria 4.000 soldiers out of 8.000 soldiers.[1] This shock cavalry division played important roles in the victories at the Battle of Chains, Battle of Walaja, Battle of Ajnadayn, Battle of Firaz, Battle of Maraj-al-Debaj, Siege of Damascus, Battle of Yarmouk, Battle of Hazir and the Battle of Iron Bridge against the Byzantine and the Sassanid.[1] Later, a splinter of this cavalry division under Al-Qa'qa ibn Amr at-Tamimi was also involved in the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah, Battle of Jalula, and the Second siege of Emesa.[1]

Equipment

[edit]

Contrary to popular belief among historians, that the Arabians during the 6th century were unarmored light cavalry raiders, Eduard Alofs argues that the Arab horsemen, whether they are Rashiduns, Ghassanids, or Lakhmids were in fact heavily armoured elite nobles,[Notes 4] akin to Cataphract in armors.[Notes 5] The Muslim army in time of Muhammad also had a particular type of body armour called "al-Kharnaq", which was characterized as flexible.[30]

For their armaments, the Early Arabic horsemens are theoretically used the following arms in battle:

- Arab sword of various types, one of the most famous types is as-Sayf al-Qala'i, a curved sword type.[30] Muhammad owned this type of sword which preserved in modern-day in Topkapı Palace museum, the sword blade were around 100 cm length which has inscription in its hilt : "Hadha Sayf al-Mashrafi li Bayt Muhammad Rasulullah". The Indian manufactured swords which used by Arabs during Muhammad era were straight and double edged.[31] certain cavalry commanders such as Amr ibn Ma'adi Yakrib, also known to possess multiple swords.[32][33] while Khalid ibn al-Walid reportedly brought at least nine swords during single battle.

- Lance used by Rashidun cavalry by swinging them during close-combat, such as in the record of record of Tabari.[34] Early caliphate cavalry held their Lance overhead posture with both hands.[35] A personal lance belong to Muhammad consisted a lance which head was made of brass.[36]

- Mounted archery with flying gallop was practiced casually by Rashidun caliphate onwards,[37][38] as it was used by early Muslim warriors such as Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, who are reported as an expert for retreating mounted shot[39] Their quivers were reportedly contained 50 arrows.[36] Leaders and commanders also obliged the usage of bows, as there are records of Muhammad himself of usage of the bow during the battle of Uhud.[36]

- Javelins also used by caliphate horsemens' their weapon. Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, a seasoned Muhajirun and early convert who always brought horses during battles,[40] were recorded have killed his enemies with javelin in at least in two occasions during his life. The first occasion when he recorded has killed Quraish nobleman Ubaydah ibn Sa'id from Umayyad clan during the Battle of Badr, who was wearing a full set of armor and Aventail that protected his entire body and face.[27] Zubayr hurled his javelin aiming at the unprotected eye of Ubaydah and killed him immediately.[27] The second occasion is during the Battle of Khaybar, Zubayr fought in a duel against a Jewish nobleman Yassir which Zubayr killed with a powerful javelin strike.[27] Firsthand witnesses reported that Zubayr brandishing himself across the battlefield during the Battle of Hunayn while hung two javelins in his back.[27]

- Rounded shield to protect the rider from arrows.[41]

Armour & horse armour

[edit]Regarding their defensive and supporting equipments, despite there is not yet archeological proof of Arabian armory before the era of Ayyubid and Mamluk found, literary sources indicates the Arabs already using body armour, such as coat of Chain mail called Dir that was found from the literary sources from the era before the advent of Islam,[42] or as an Umayyad poetries that mentioned the armour of the caliphate army during caliph Umar until Umayyad era.[41] During the Battle of Uhud, Jami'at Tirmidhi recorded Zubayr ibn al-Awwam testimony that Muhammad wearing two layers of mail coat.[43][44] However, there is still not yet archaeological founding of Arabic armor in such time.[45] Waqidi recorded the Qurayshite Arab horsemens also using horse armor which held by Crupper on the back of the horse, which are used by a Qurayshite warrior named Hubayr ibn Abi Wahb al Makhzumi during the battle of the Trench.[46]

The Muslim Arabic cavalry during early caliphate already knew of stirrups. However, caliph Umar forbid or neglected the use of stirrups for his soldiers as riding without stirrups could train riders better for horsemanship.[47][48] Despite the rejection or neglect of stirrups,[49][50] Arab cavalry, especially the Kharijites group who will revolt after the conquest, were feared for their fearless charge, which, as Adam Ali mentioned in his work on al-Jahiz, "can throw any defense line into disarray".[2] Military history reconstructors like Marcus Junkelmann have determined from historical reenactment that mounted close combat specialists like Mubarizuns could fight effectively on top of their mounts without stirrups.[49] This is used by Alofs as an argument to debunk the assertion held by most historians that horsemen cannot fight effectively in close combat without the use of stirrups.[49]

David Nicolle brought the theory of Pre-Islamic Arabia Arabic-speaking peoples adoption of armory among horsemen as he quoted Claude Cahen, who categorically stated that horse armor was very common in the early Islamic period.[51] Nicolle thought those Arabians were exposed to external culture influences such as from external military influence from Turkish Uyghurs, originating in Xinjiang, which then spread further to Iran and beyond, eventually reaching the Middle east,[51] Nicolle divided the evidence from three pinpoint areas:

- Dura-Europos, located in Syrian borderlands of the Byzantine Empire, where horse armor of bronze scales, Roman Syria or Parthian origin, from the 3rd century AD are found.[51] Although Nicolle dismissed the Byzantines as being unlikely as heavily armoured cavalry were not Byzantine tradition in the first place, and only adopted such in the late era, unlike the Persians.[51]

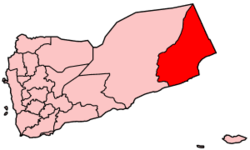

- Shabwa, Yemen, as Nicole pointed there is carved plaque depicting armoured cavalry, both the rider and the horse, which Nicolle surmised originated from 6th–early 7th AD, and theoretically were Asawiran Sassanids heavy cavalry who garrisoned Yemen for decades before the expansion of Islam circa 570 to 630 AD.[51] While Ogden pointed out Yemen were also known as an important coastal sea trade between India and the Red Sea since ancient times and were exposed to the latter's metallurgy.[52] the team of Bir Hima archeology excavation and researchers has found southwestern edge of the modern city of Najran, a depiction of a heavily built horse similar in form to the extinct Nisean horse breed which rode by Zaweyan elite troops of Sassanids of the 6th century BCE, which according to the team, indicating Persian influence.[53] Elwyn Hartley Edwards also added it is possible that the Arabs also had influence in the breeding of legendary Nisean horses, since geographically the breed theoritically was bred in western Iran of Medes.[54] Edwards further remarked the possibility that the Nisean were also infused with Arabian horse breed.[54]

- Wadi Aday, 8 km south of Muttrah, Oman.,[51] where Nicolle pointed out many armoured horsemen carvings, armed with spears and a sword, that, according to Nicole, traditionally identified as Arabs.[51] according to researchers, south-eastern Arabia including Oman has for a long time been exposed to Iron since the Iron Age, which presumably is from external influence such as India, just as for Yemen.[55] Regarding this theory, Nicolle suggested the horse armour adopted by Pre-Islamic Oman and Yemen Arabs which he implied from Sasanian Yemen influence.[56]

Aside from those three locations that are pointed by Nicolle, Bir Hima archaeological researchers team also found evidence of Arabian armoured cavalry in the form of hundreds, if not thousands of petroglyphs in Bir Hima, which is located about 30 km northeast of Najran.[53] The excavation sites are dominated by images of mounted cavalry that are highly stylized, which the researchers theorized riding Arabian breed horses.[53] The cavalrymen are armed with long lances, swords, Sayf swords and khanjar daggers which are worn in the waist.[53] The team also notice that there are indication the carvings of those horsemen probably wearing something like helmets and cutlasses.[53]

Military standard

[edit]Before the advent of Islam, banners as tools for signaling had already been employed by the pre-Islamic Arab tribes and the Byzantines. Early Muslim army naturally deployed banners for the same purpose.[57] Early Islamic flags, however, greatly simplified its design by using plain color, due to the Islamic prescriptions on aniconism.[58] According to the Islamic traditions, the Quraysh had a black liwāʾ and a white-and-black rāya.[59] It further states that Muhammad had an ʿalam in white nicknamed "the Young Eagle" (Arabic: العقاب al-ʿuqāb); and a rāya in black, said to be made from his wife Aisha's head-cloth.[60] This larger flag was known as " the Banner of the Eagle" (Arabic: الراية العقاب al-rāyat al-ʻuqāb), as well as "the Black Banner" (Arabic: الراية السوداء ar-rāyat as-sawdāʾ).[61] Other examples are the prominent Arab military commander 'Amr ibn al-'As using red banner,[62] and the Khawarij rebels using red banner as well.[63] Banners of the early Muslim army in general, however, employed a variety of colors, both singly and in combination.[64]

According to modern historian David Nicolle in Warrior magazine series published by Osprey Publishing, as the caliphate army were mainly consisted of tribal based corps and divisions, most of the following flags appeared in the Battle of Siffin on both sides:

- The black standard

- The red standard that used by Amr ibn al-As and later by the Kharijites

- The Ansars flag

- The Quraysh flag

- The Quraysh second flag

- The Quraysh third flag

- The Taym tribe flag

- The Thaqif tribe flag

- The Hawazin tribe flag

- The Shayban tribe flag

- The Muharib tribe flag

- The Ghani & Bahila tribe flag

- The Tayy tribe flag

- The Kinanah tribe flag

- The Kalb tribe flag

- The Nukha tribe flag

- The Ju'fa tribe flag

- The Judham tribe flag

- The Hudhayl tribe flag

- The Hamdan tribe flag

- The Dhuhal tribe flag

- The 'Akk tribe flag

- The first Ajal tribe flag

- The second Ajal tribe flag

- The Khuza'a tribe flag

- The Yashkur tribe flag

- The Hanzala tribe flag

- The Sa'd ibn Zayd Manat tribe flag

- The Kindah tribe flag

- The Bajila tribe flag

- The Khath'am tribe flag

- The first Taghlib tribe flag

- The second Taghlib tribe flag

- The Sulaym tribe flag

- The Quda'ah tribe flag

- The flag of the tribes from Hadhramawt

Training, tactics & strategy

[edit]As the mainstay strategy of the Rashidun army were interchangeably and derived from Islamic teaching, the main doctrine of the Rashidun cavalry also borrowed from the religious ethic itself, as example the aim for building such military sophistication were in fact aimed to cause fear and discourage the enemy from offering resistance, and if possible, cause the enemy to submit peacefully, as it is said the main idea from Verse Quran chapter al-Anfal verse[Quran 8:60].[65]

Aside from that distinguishing role which characterized by the Mobile Guard cavalry were their task to plugging the gaps between Muslim ranks to avoid enemy penetration, which they practiced during the battle of the Yarmuk.[13] During the reign of caliph Umar. The caliph instructed Salman Ibn Rabi'ah al-Bahili to establish systematic military program to maintain the quality of caliphate mounts. Salman enlisted most of the steeds within realm of caliphate to undergo such steps:[66]

- Recording number and quality of horses available.

- Differences between the Arabian purebreed and the hybrid breeds was to be carefully noted.

- Arabic structural medical examination and Hippiatrica on each horses in regular basis including isolation and quarantine of sick horses.

- Regular training between horses and their masters to achieve the disciplined communication between them.

- Collective response training of the horses done in general routine.

- Individual response training of the horses on advanced level.

- Endurance and temperament training to perform in crowded and noisy places.[67]

Meanwhile, technical training method of each horsemen in this cavalry was recorded in al-Fann al-Harbi In- Sadr al-Islam and Tarikh Tabari:[66]

- Riding horses with saddles.

- Riding horses without saddles.

- Sword fighting without horses

- Horse charging with stabbing weapons.

- Fighting with swords from the back of a moving horse.

- Archery.

- Mounted archery while the horse running.

- Close combat while changing their seat position on the back of moving horse, facing backwards.

At the end of the program, both riders and horses obligated to enlisted in formal competition sponsored by Diwan al-Jund which consisted into two category:

- Racing competition to measure the speed and stamina of each hybrids.[37] This racing activities are also encouraged by caliphate commanders such as Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah who himself also engaged in such sport.[68]

- Acrobat competition to measure the ability of the horses for difficult maneuvers during war.[37]

Additionally, In the wartime, there are special trainings established cavalry divisions were obliged to undertook:

- simulated combat operation raids during the winter and summer seasons, known as Tadrib al-Shawati wa al-Sawd'if, which were intended to maintain the quality of each cavalry forces, while also maintain the pressures towards the Byzantines, Persians, and other caliphate enemies while there is no major military campaign.[37]

- Special drills that required for particular operasion, such as during the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah, The Muslim cavalry undergo drill training that involved by maneuvering their horses nearby elephant dummy statues, to train the horses so they did not afraid during the battle as they were tasked to charge against Sasanian Empire elephant corps[69]

Cavalry archery

[edit]Alof theorized "Mubarizun" elite division, a unit specialized in close combat duels, also used archery in close-combat duels for maximum arrow penetration against opponent armor.[70] This select few apparatus of mounted soldiers who particularly skilled in duel were tasked to find the enemy generals or field officers, in order to kidnap or slay them in close combat, so the enemy will lose their commanding figure amidst of battle.[71] Aside from fighting with swords, lances, or maces, these duel specialists also possessed a unique ability to use archery in close combat, where Alofs theorized that in mid range about five meters from the adversary, the duelists will exchange his lance with his bow and shoot the enemy from close range to achieve maximum penetration, while the duelist held the lance strapped between right leg and saddle.[72] In fact, James Hardy theorized based on his quote from John Haldon and Romilly Jenkins, one of the decisive main factor for the Rashidun historical victory in battle of Yarmuk were due to their superb cavalry archers.[73] While James Francis LePree has written that the factor of "unquestionably great cavalry skill of the Arabs' horse archers" during the battle of Yarmuk.[74]

Cavalry archers also used to bait the opposing army from their position, which were reported by Tabari during the battle of Nahavand, when Tulayha planned to lure the bulk of enemy forces by sending armoured cavalry archers forth and shooting them while retreating to bait them to the favorable terrain for Muslim army to fight the Sassanids.[75]

Cavalry usage during siege warfare

[edit]The tactics used by Iyad ibn Ghanm in his Mesopotamian campaign were similar to those employed by the Muslims in Palestine, though in Iyad's case the contemporary accounts reveal his specific modus operandi, particularly in Raqqa.[76] The operation to capture that city entailed positioning cavalry forces near its entrances, preventing its defenders and residents from leaving or rural refugees from entering.[76] Concurrently, the remainder of Iyad's forces cleared the surrounding countryside of supplies and took captives.[76] These dual tactics were employed in several other cities in al-Jazira.[76] They proved effective in gaining surrenders from targeted cities running low on supplies and whose satellite villages were trapped by hostile troops.[76]

Ubadah ibn al-Samit, another Rashidun commander, is also recorded to have developed his own distinct strategy which involved the use of cavalry during siege warfare. During a siege, Ubadah would dig a large hole, deep enough to hide a considerable number of horsemen near an enemy garrison, and hid his cavalry there during the night. When the sun rose and the enemy city opened their gates for the civilians in the morning, Ubadah and his hidden cavalry then emerged from the hole and stormed the gates as the unsuspecting enemy could not close the gate before Ubadah's horsemen entered. This strategy was used by Ubadah during the Siege of Laodicea[77][78] and Siege of Alexandria.[77]

Mounts

[edit]The possession of horse among Arab peoples were long time traditionally considered as symbol of wealth and prestige.[79] The musing of pure Arabian horse breed in Arab community social standing also found in the dialogue between caliph Umar with one of his cavalry commander, Amr ibn Ma'adi Yakrib, which recorded in the Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd anthology of adab authored by Ibn Abd Rabbih.[80] According to Schiettecatte, Earliest osteological evidence for the horses in Arabia were found in Bahrain in a middle of the 1000 BC.[81] The developments of early cavalry regiments within caliphate were effected due to the availability of the rich Meccan Arabs to field sufficient horses.[79]

Notables among Arab Muslims, especially those of Companions of the Prophet, were recorded possessed multiple horses & camels privately, such as Khalid ibn al-Walid, who reportedly possessed at least 16 horses which all named.[82] This practice of possessing multiple horses were not unlike Amr ibn Ma'adi Yakrib, the cavalry commander who had mythical reputation, also had at least four named horses of his own,[32] which number grown further as later the governor of Basra rewarded Amr with foal pregnant mare with preserved pedigree from al-Ghabra type (dust colored type).[83] Meanwhile, other warriors like Zubayr ibn al-Awwam owns a swooping number of 1,000 horses in his private stable.[84] while on the other hand, Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf reportedly possessed hundreds of horses and 1,000 camels, [85] and Dhiraar ibn al-Azwar, who also reportedly owns about 1,000 camels even before embracing Islam and pledge his allegiance to the Caliphate.[Notes 6]

Horses

[edit]

Caliphate Arabian noble cavalry[Notes 7] almost certainly rode the legendary purebred Arabian horse, by fact the quality breeding of horses were held so dearly by the early caliphates who integrated traditions of Islam with their military practice.[4][5][6][7] The soldiers who possessed the pureblood Arabian horse even had the right to acquire bigger war spoils after battles than the soldiers who used other breeds or hybrid breed horses.[87] The horses are culturally related with war in pre-Islamic Arabia as described in the long poems by Antarah ibn Shaddad and Dorayd bin Al Soma.[88]

These horses are also pretty common breed amongst Arab community during 6th to 7th century.[4] This special breed of steed were famous for their speed which allowed for large-scale conquests of the caliphate during their early days.[4][47] The Arabian breed is forged by the harsh life in desert and raised by nomadic Bedouins who spread it throughout their travels, and erect it as a symbol of social and cultural status, in parallel with a martial selection.[89] This breed are known as a hot-blooded breed that are known for their competitiveness. Long withstanding periods of Arabian nomadic society closeness with the horses also contributed to fertility of equestrian masters which produced best class horse breed in Arabia.[90] The phenomenal speed, stamina, intelligence, along with very well documented pedigrees quality even for modern era standard,[91][92] caused the Rashidun leaders to initiate a formal programs to distinguish them from inferior hybrids with unknown pedigrees including horses recently captured from the defeated enemies.[37] Earlier attempts of Muslim horse-breeding were found in the aftermath of Siege series of Khaybar fotresses when the Muslims acquired massive booties of horses from the Jewish castles. In response Muhammad personally instructed the breeding separations between purebred Arabian and the hybrid-class steeds.[67] in later cases, such tradition of glorifying the breed of pure Arabian steeds are recorded by caliphate soldiers during the conquest of Persia.[93] While another detailed example were Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, who owned many horses.[84] The most famous Arabian horse that owned and being named by az-Zubayr were al-Ya'sūb, which he ride in the Battle of Badr.[94] al-Ya'sūb pedigree was preserved carefully by az-Zubayr's clansmens, banu Asad ibn Abd al-Uzza branch from Quraysh tribe, who create a system of "horse-clan", the "horse-clan" system of recording their horses ancestry and lineage are meant carefully maintain the horses genealogical purity and quality while also manage to keep the steeds genealogy traceable, as in al-Ya'sūb case, who belong to a horse-clan namely al-Asjadi.[95] the al-Asjadi horse clan were keep by az-Zubayr for generations.[95]

Al-Baihaqi transmitted in Shuab al-iman about "Birdhaun breed", or horse of poor breed that are hailing not Arabian breed, more specifically a Turkish horses breed, which caliph Umar warned his governors against riding such horses.[96] According to Bayhaqi, prohibiting a breed considered second-rate makes it obvious that to ride horses of the best Arab breed would be even a greater sign of pride.[96] The Arabian theory were justified in the medieval tradition as Mamluk Furusiyya treatises of hippiatry distinguished lineages of Arabian horses were named based on their geographical provenance (Hejaz, Najd, Yemen, Bilād al‑Shām, Jezirah, Iraq), the noblest breed, according to Ibn al‑Mundhir were the Hijazi breed.[97]

The early caliphate army preferred mares than stallion as warhorses.[98] Khalid ibn al-Walid were said preferred mare by reason it believed that the mares were more fitt for cavalry combats.[98] The specific explanation is that mares are not as vocal as either horses or geldings, and the Arabs often believed mares did not need to stop to urinate, which saves times of the army mobilization.[98] Another reason for the Arabian cavalry to uniformly prefer mares during battles because bringing stallions during combat can potentially disrupt the riders rank as the mares in heat can incite stallions libido and caused the stallion difficult to control.[98]

Mahranite cavalry

[edit]

Caliphate cavalry recruited from Al-Mahra tribe were known for their military prowess and skilled horsemen that often won battles with minimal or no casualties at all, which Amr ibn al As in his own words praised them as "peoples who kill without being killed",[Notes 8]

Ibn Abd al-Hakam remarks their relative minimal casualties whenever engaged in military operations. Amr was amazed by these proud warriors for their ruthless fighting skill and efficiency During Muslim conquest where they spearheaded Muslim army during the Battle of Heliopolis, the Battle of Nikiou, and Siege of Alexandria.[99] Their commanders, Abd al-sallam ibn Habira al-Mahri were entrusted by 'Amr ibn al-'As to lead the entire Muslim army during the Arab conquest of north Africa. Abd al-sallam defeated the Byzantine imperial army in Libya, and throughout these campaigns Al-Mahra were awarded much land in Africa as recognition of their bravery.[99] When Amr established the town of Fustat, he further rewarded Al-Mahri members additional land in Fustat which then became known as Khittat Mahra or the Mahra quarter.[99] This land was used by the Al-Mahra tribes as a garrison.[99]

During the turmoil of Second Fitna, more than 600 Mahranites were sent to North Africa to fight Byzantines and the Berber Kharijite revolts.[99]

Camels

[edit]Aside from horses, Rashidun cavalry used camels as their means of transportation as they want to save their horses energy, while outside the battle, the camels were used to transport the provisions of the soldiers, as each soldiers of the caliphate were expected to provide his own provisions at the very least outside the main army provided by the leaders or wealthy soldiers.[36]

During the battle, the Rashidun cavalry immediately change their ride to the horses, while their camels are hobbled along the defensive perimeters of Muslim army.[11] Their camels are used defensively during battle as the bulk of camel lines perimeter will blunt the enemy heavy cavalry charge[11] Sometimes, these Arab cavaliers also recorded to ride their camels simultaneously with their horse in one battle depending on the situation, as recorded in the report about Muslim horsemen named Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, when he fought on the Battle of the Yarmuk, at one point he is reported charging with his horse, breaching the Byzantine army line.[100] While in the same battle, he also reported has changed his ride to camel, while fighting defensively and praying at the same time.[101]

Aside from carrying provisions, transportations, and for battle usage, the camel mares were valued for their milk production for the warhorses daily nourishments.[79] The camels milk reserved as substitution for the Rashidun army horses drink whenever water supply unavailable. [79] Two camel mares milk were expected to nourish one horse each day.[79]

Emergency rations & Khalid legendary camels march

[edit]

Desperate caravaners are known to have consumed camels' urine and to have slaughtered them when their resources were exhausted.[102]

Around 634, after the clash at the Battle of Firaz against intercepting Byzantine forces, caliph Abu Bakr immediately instructed Khalid to reinforce the contingents of Abu Ubaydah, Amr ibn al-As, Mu'awiyah, and Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan which started to invade Syria. Khalid immediately started his nearly impossible journey with his elite forces after leaving Muthanna ibn Haritha as his deputy in Iraq and instructed his soldiers to make each camel drink as much as possible before they started the six-day nonstop march without resupply.[103][Notes 9] In the end, Khalid managed to reach Suwa spring and immediately defeated the Byzantine garrison in Arak, Syria,[105] who were surprised by Khalid's force's sudden emergence from the desert.[106]

According to Hugh Kennedy, historians across the ages assessed this daring journey with various expressions of amazement. Classical Muslim historians praised the marching force's perseverance as a miracle work of Allah, while most western modern historians regard this as solely the genius of Khalid.[107] It is Khalid, whose, in Hugh Kennedy's opinion, imaginative thinking effected this legendary feat.[107] The historian Moshe Gil calls the march "a feat which has no parallel" and a testament to "Khalid's qualities as an outstanding commander",[108] while Laura Veccia Vaglieri dismissed the adventure of Khalid as never having happened as Vaglieri thought such journey were logically impossible.[109] Nevertheless, military historian Richard G. Davis explained that Khalid imaginatively employed camel supply trains to make this journey possible.[103] Those well hydrated camels that accompanied his journey were proven before in the Battle of Ullais for such a risky journey.[110] Khalid resorted to slaughtering many camels for provisions for his desperate army.[103]

Rashidun army camels also bore offspring while marching to the battle, as Tabari recorded the Rashidun vanguard commander Aqra' ibn Habis, testified before the Battle of al-Anbar, the camels belongs to his soldiers were about to give birth. However, since the Aqra' would not halt the operation, he instructed his soldiers to carry the newborn camels on the rumps of adult camels.[111]

Mahranite camelier corps

[edit]Amr ibn al-As led a ruthless cavalry corps from tribes of Al-Mahra who were famous for their "invincible battle skills on top of their mounts", during the conquests of Egypt and north Africa[Notes 10]. Al-Mahra tribes were experts in camelry and famed for their high-class Mehri camel breed which were renowned for their speed, agility and toughness.[99]

Hima breeding ground

[edit]

Hima natural reserve which instituted by the early leaders of Islam caliphate were one of the main factor for their army to be able to keep supplying mounts in large numbers.[79] This breeding institution were formed by the caliphs Nejd, where the steppe vegetation apparent in Arabia.[79] The Hima breeding fields were consisted of large area maintained the vegetative and the animals could lived and bred completely free, as no one are allowed to enter the Hima except the rightful owner of the animals which bred on there.[79]

The history of Hima breeding grounds preservation as an effort to supply the army with mounts were rooted from the early Islam period, where Modern Islamic studies researchers theorized institution of Hima by caliph Umar, who inspired by the earliest Hima established in Medina during the time of Muhammad.[112] Muhammad has declared the valley of Naqi (Wadi an-Naqi) to be reserved for the army mounts usage.[113] Another known Hima breeding grounds during the caliphate were in Kufa, which supervised by Rabi' al Kinda, father in law of the son of Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, governor of Kufa during caliphate of Umar and Uthman.[114] Muhammad himself instructed that some of private property at the outskirts of Medina was transformed into Hima.[115] Banu Kilab tribe from Hawazin confederation were known to manage the Ḥima Ḍarīyya in Nejd.[116][117][119]

Caliph Umar particularly ordered the extensive establishments of Hima in the conquered areas in Iraq and Levant after the battle of Yarmuk and the battle of Qadisiyyah, as the Rashidun caliphate gained large swath of territory after those two battles.[79] Another reason the caliph Umar moved Hima from Medina was the increasing military demand for camels for which the lands near Medina no longer sufficed.[112] According to classical Muslim sources, caliph Umar acquired some fertile land in Arabia which were deemed fit for large-scale camel breeding to be established as Hima, government-reserved land property used as pasture to raise camels that were being prepared to be sent to the front line for Jihad conquests.[120] Early sources recorded that the Hima of Rabadha and Diriyah produced 4.000 war camels annually during the reign of Umar, while during the reign of Uthman, both Hima lands further expanded until al-Rabadha Hima alone could produce 4.000 war camels.[121] At the time of Uthman's death, there were said to be around 1.000 war camels already prepared in al-Rabadhah.[121]

The Hima breeding program of stockbreeding were soon adopted by the Ghassanids Arabs who supplied horses to the Byzantines.[79] The Lakhmids Arabs in Iraq who used the Persian breed as their horses, also adopted the Hima system with success.[79] The Hima breeding grounds in Nejd survived until the 20th century during the reign of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia government abolished those reserve places in 1957.[122] The reason of the abolition were presumed by Shamekh as the effort of Saudi government to encourage sendentarization.[122]

Legacy

[edit]Modern historians and genealogists concluded that the stocks of early caliphate cavalry army that conquered from the western Maghreb of Africa, Spain to the east of Central Asia are drawn from the stock of fierce Bedouin pastoral nomads who take pride of their well-guarded mares genealogy,[123][124][125][126] and called themselves the "People of the lance".[Notes 11] Thus, this caused many aspect of influences, whether the Animal breedings[127] or another social and religious development within the territories they have conquered,[128] Including Indian subcontinent.[129]

Horsebreeding

[edit]- Gray Arabian mare in Egypt

- Mughal horse headgear, collection from Lamongan Museum, Indonesia

- Carl Raswan riding Anazeh tribe horse

- Amir Saud mounted army 18-19 AD

- Barb horse "Fantasia" ridings in Morocco

The Mammals beast of burden brought by these desert warriors on horseback in massive scale unanimously agreed by historians and breeding researchers as bringing some degree of cultural influences towards their subjugated lands, whether it by the massive scale utilization of dromedaries,[126][130] or their horses, as Muslim conquests of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula brought large numbers of Arabian horses,[25] The regular supply of horses from Hima breeding grounds has taken effect particularly after Muslim conquest of Persia, North Africa, and central Asia.[79]

The Barb horse may have come with the Umayyad Caliphate army who settled in the Guadalquivir valley, as both the Arabian strain were brought by the Muslim empires to Europe, which implied by Margareth Greely, through military mean.[127] The Barb horse spread theory were supported by Helen Goldstein who theorized about how the conqueror of Spain, Tariq ibn Ziyad brought the Barb horses along with the Arabian strain during the Muslim conquest of Iberia, as the Barb horses are favored for spare mounts by forces of Tariq as Goldstein theorized the Muslim invaders prized the Arabian breed so much, so they keep them most of the times, while they used the Barbs for trivial routines. The Barbs brought by them crossbreeded through ages with native Spanish horses.[131] Barbs crossbreedings with Spanish stock under 300 years of Umayyad patronage has developed the Andalusian horse (and the Lusitano) breeds.[132] Regarding the Portuguese claimed Lusitano breed, Juan Valera-Lemait noted the evidence of the exchange of blood between the Iberian breeds with Barb breeds were mutually beneficial, to the point that modern Barb more resembling the Iberian breed stock as well as the criollo horses of South America. while the introduction to America continent were related to the Muslim invasion medieval era, when Spain and Portugal were in constant war with the Berber invaders where horse and horsemanship had become finely attuned to the war exercises. Thus resulted the Conquistadors introduced and dispersed the breed throughout America.[133]

Meanwhile, the genetics strength of the desert-bred Arabian horse, Arabian bloodlines have played a part in the development of nearly every modern light horse breed, including the Orlov Trotter,[134] Morgan,[135] American Saddlebred,[136] American Quarter Horse,[135] and Warmblood breeds such as the Trakehner.[137] Arabian bloodlines have also influenced the development of the Welsh Pony,[135] the Australian Stock Horse,[135] Percheron draft horse,[138] Appaloosa,[139] and the Colorado Ranger Horse.[140] In modern era, peoples cross Arabians with other breeds to add refinement, endurance, agility and beauty. In the US, Half-Arabians have their own registry within the Arabian Horse Association, which includes a special section for Anglo-Arabians (Arabian-Thoroughbred crosses).[141] Some crosses originally registered only as Half-Arabians became popular enough to have their own breed registry, including the National Show Horse (an Arabian-Saddlebred cross),[142] the Quarab (Arabian-Quarter Horse),[143] the Pintabian[144] the Welara (Arabian-Welsh Pony),[145] and the Morab (Arabian-Morgan).[146]

Another possible strain of horse that came to Europe with these Islamic cavalry invaders was the Turkoman horse,[26] which was possibly brought from Muslim conquest of Transoxiana and Persia.

Mamluk horse

[edit]The successful Hima breeding programs of the early caliphates has effected the inexhaustable supply of manpowers and warhorses, which extended to the Mamluk Sultanate 150 years of cavalry superiority before the advent of firearms.[79]

Aside from practical military use, The breeding of pure Arabian breed were practiced by the military regime of Mamluk as way to gain social prestige in a middle of Arabian aristocratic society in Egypt, Sham, and Hejaz.[97] Since the Mamluks were hailed from slave backgrounds, which consisted from Turkic peoples from the Eurasian Steppe,[147][148][149] and also from Circassians,[148][150] Abkhazians,[151][152][153] Georgians,[154][155][156][157] Armenians,[158] Albanians,[159] Greeks,[154] South Slavs[154][159][160] (see Saqaliba) or Egyptians.[161] The Mamluk though that the genealogical purity of their steeds were symbols of martial horsery culture of Arabians, religious purity, and military might.[97]

Arabian horses also spread to the rest of the world via the Ottoman Empire, which rose in 1299. this Turkish empire obtained many Arabian horses through trade, diplomacy and war.[7] The Ottomans encouraged formation of private stud farms in order to ensure a supply of cavalry horses.[162]

Delhi Sultanate & Mughal empire

[edit]During the Umayyad campaigns in India, Muhammad ibn Qasim has brought cavalry of 6000 riding fine Arabian Horses.[163] Since then, exports of horses via the maritime routes through the Persian Gulf, supplied mainly from Arabian peninsula and southern Iran has flowed through India.[164] Since then, the Muslim regimes in India has undergoing extensive cavalry army building which revolved around the Arabian horse, such as Delhi Sultanate,[129] and also the Mughal empire,[165] as it is attested further by the period of Mughal of the 16th to 17th century, when horses were imported from the countries of Arabia, Iran, Turkey and Central Asia to India.[166]

the Bhimthadi horse, or Deccani horse breed, gets its name from the vast Deccan Plateau in India. A major trade in Arabian horse breeds in the ports of Deccan began after the Bahamani Sultanate revolted against the Delhi Sultanate.[167] The Bhimthadi breed was developed in Pune district in 17th and 18th centuries during the Maratha rule by crossing Arabian and Turkic breeds with local ponies.[168][169]

Rise of Saudi

[edit]Arabian horses were classified based on their geographical provenance by their bedouin masters, such as Hejaz, Najd, Yemen, Bilād al‑Shām, Jezirah, or Iraq breed as example.[97]

The Najd breed were somehow found their prominence both in warfare and cultural heritage in accordance with the rise of their master's regime, House of Saud and Wahhabism religious movement which spanned from the time of Wahhabi War on early 18th AD century, towards the aftermath of World War I.[170] During Unification of Saudi Arabia war, high ranked Arabian peninsula desert communities such as Sharif of Mecca and the first Saudi Emirate put emphasis on their Arabian horse breedings, in well documented records from Carl Raswan and other desert researchers.[170]

In modern era, royal family from Kingdom of Saud also known for their love for breeding horses and spent expenses for such effort.[171]

Islamic ruling regarding war horses breeds

[edit]The profound tradition of Arabian horse breeding exaltation by early caliphate soldiers even became a basis for scholars of later era. Muslim jurists who codified Islamic law from the mid‑eighth century to strongly connect the horse with Jihad, as They especially stated that it should receive shares in the plunder: two parts of the fourth‑fifths share by Maliki, Shafiʽi school and Hanbali, while one for Abū Ḥanīfa.[97] Accordingl, there are belief in Islam about the Arabian horses which found in Hadith that an Arabian breeds were praying for their owners to God two times a day.[172]

Shafi'i jurist, Al-Mawardi, to establish the ruling of regular military share that the owner of noble purebreed Arabian(al‑khayl al‑ʿitāq) should be rewarded a share of booty three times of regular infantry soldiers, while owners of inferior mixed breeds received only twice infantry soldiers' share.[5] Al-Mawardi seems based his ruling from hadith tradition from companion of the prophet named Abd Allah ibn Amr ibn al-As.[97] While Ahmad ibn Hanbal ruled that "a mixed‑breed birdhawn (al‑birdhawn al‑hajīn) should be given the half share of the noble Arabian [horse] (al‑ʿarabī al‑ʿatīq). Henceforth, the rider (fāris) of the birdhawn should be given two shares whereas the rider of the noble Arabian horse should be given three shares"[97] The related tradition of cavalry spoils privilege from Miqdad ibn Aswad[Notes 12] and Zubayr ibn al-Awwam privileged share of five times that of normal soldiers by the ruling that Zubayr were owner of warhorse and also a relative of Muhammad were discussed by modern Salafi scholars as valid rules based on those hadiths.[Notes 13]

Military, religious & political Legacy

[edit]

Chroniclers recorded Kharijites as among fiercest and most zealous element within caliphate cavalry hailed from the Bedouin tribes of Arabs[2] and Berbers,[175][Notes 14] that will later revolt against their own caliphate.[128] 8th century chronicler, Al-Jahiz noted Kharijites horsemen ferocity, who spent parts of their early career in Kufa as Rashidun garrison troop during the Muslim conquest of Persia.[177]

The Kharijites were feared for their powerful cavalry charge with their lances which could break any defensive line, and almost never lose when pitted against equal number of opponents.[2] This claim also supported by Akbar Shah Khan Najibabadi, who has given measure that a valiant Kharijite army sometimes could even defeat an opponent whose number were ten times or twenty times bigger than them.[178] The testament Kharijites prowess are when the Kharijites quietists faction[Notes 15] led by Abu Bilal Mirdas,[Notes 16] who hailed from Tamim tribe decimated the 2,000 Umayyad force from Basra under Aslam ibn Zur'a al-Kilabi, with only forty men in the encounter at the village of Asak near Ramhurmuz.[181][182][183]

Meanwhile, Al-Jahiz also pointed out Kharijites steeds' speed could not intercepted by most rival cavalrymen in medieval era, save for the Turkish Mamluks,[2] As Tabari recorded the stamina and nimbleness of Kharijites, where they will even retreat long time, as it takes early morning until time for Salah prayer for Abu al-Rawwagh, caliphate commander, to pursue them without breaking down.[184]

Furthermore, legendary perseverance of the Kharijites in history were recorded several times in the medieval chronicles, such as when Abd al-Rahman ibn Muljam, member of Kharijite assassin who murdered Ali, did not flinch in pain or shown fear when his arms, legs, and eyes mutilated by Ali sons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali, before being executed. Ibn Muljam only shown fear when it is his tongue are about cut, due to his reason that if his tongue were cut, he cannot pray with his mouth again before executed.[185][186] or when the Ibadi Rustamid warriors under Abd al-Wahhab ibn Abd al-Rahman are said never flinched against hails of enemy arrows, and even laughed when arrows stuck on their bodies.

Hurqus & Iraqi Kharijites

[edit]According to Al-Shahrastani, an 11th AD century Shafiite scholar, the proto Kharijite group were called al-Muhakkima al-Ula.[187] they were rooted in the Muslim warriors existed in the times of Muhammad.[21] the al-Muhakkima al-Ula group were led by a figure named Dhu al-Khuwaishirah at-Tamimi,[188] more famously known as Hurqus ibn Zuhayr as-Sa'di, a Tamim tribe chieftain, veteran of the Battle of Hunayn and first generation Kharijites who protested the war spoils distribution.[21][22] Hurqus were recorded being prophesied by a Hadith from Muhammad that he will revolt against Caliphate later.[189]

At first, Hosts of Hurqus were among those who participated in the Muslim conquest of Persia led by Arfajah, Rashidun general who commands the army and navy in Iraq. During Conquest of Khuzestan, Hurqus defeated Hormuzan in 638 at Ahvaz (known as Hormizd-Ardashir in modern era) to subdue the city.[190] However, later during the reign of Uthman, Hurqus was one of the ringleaders from Basra that conspired to assassinate Uthman.[189] They are the soldiers of Ali during the battle of Siffin, who later rebelled towards the Caliphate of Ali and planned their rebellion in the village of Haruri.[187] Despite being suppressed by Ali, remnants of Hurqus group of Muhakkima al-Ula or the Haruriyya proto-Kharijites has survived and would later influenced the splinter sects of Azariqa, Sufriyyah, Ibadiyyah, Yazidiyyah, Maimuniyyah, Ajaridah, al-Baihasiyyah, and the Najdat radical sects.[187][Notes 17] These violent warrior sects would plague the entire history of Rashidun Caliphate, Umayyad, and Abbasid with endemic rebellions.

The host of Hurqus also contained another troublesome Kharijite embryos that also came to Iraq under Arfajah were the ones that hail from Bajila tribe,[23] Notable seditionist warriors from this tribe were Abd Allah ibn Wahb al-Rasibi, who participated in the early conquests of Persia under Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas.[24] and later joined the hosts of Hurqus against caliphate of Ali in the battle of Nahrawan.[128]

Scholars evaluations about Kharijites

[edit]According to Shafiite scholar Abdul Qahir ibn Thahir Bin Muhammad Al Baghdadi in his book of encyclopedia of astray sect within Islam, al-Farq bain al-Firaq, The Azariqa were the most strongest faction with biggest followers.[187] They are the first target by Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr to be suppressed, who sent Al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra for the operation.[187] Despite their military strength and fanatical zealotry, the Azariq followers were superficially prone to disunity and Divide and rule strategy launched by Muhallab, who acknowledged of the shallowness of the Azariqa Jihad concept when faced by Muhallab own jurists, engaging some religious debate towards some of their key members of the Kharijites regarding the flaw of their Islamic practice and Jihad, thus enticed most of them to indirectly serving Muhallab by striking their own allies.[187] This fatal flaw were, according to Akbar Shah Najibabadi, the reason why Muhallab never lose his battle against the fearsome Kharijites, while seven of Muhallab sons also shown exemplarly success during anti-Kharijite operations.[178]

Dr. Adam Ali M.A.PhD. postulated that Al-Jahiz's assessment of the military quality of Kharijites are synonymous with the regular Arab cavalry in general term of speed and charging maneuver.[2] In fact, ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Ḥabīb, a jurist and historian in the 9th century described the Berber Kharijites as a mirror match for the Caliphate army, as they are resembling the Arabic caliphate martial tradition, except for the loyalty to authority.[175] Ibn Nujaym al-Hanafi, Hanafi scholar, outlined his evaluation about Kharijites: "... kharijites are a folk possessing strength and zealotry, who revolt against the government due to a self-styled interpretation. They believe that government is upon falsehood, disbelief or disobedience that necessitates it being fought against, and they declare lawful the blood and wealth of the Muslims...”.[128]

Scholars of later such as Al-Dhahabi, Abu Dawud al-Sijistani Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen, and Majd ad-Dīn Ibn Athir era has observed the historical influence of Dhu al-Khuwaishirah Hurqus at-Tamimi and Abu Bilal Mirdas at-Tamimi on their commentary notes as a warning against the danger of Khawarij, even when they are just criticizing the superiors in public and not openly rebelled.[180][179]

See also

[edit]- Khalid ibn Walid

- Rashidun Caliphate army

- Early Caliphate navy

- Companion cavalry (elite cavalry of Alexander's Macedonian army)

- Muslim conquest of Syria

Notes

[edit]- ^ Waqidi recorded that around 5,000 Sahabah were fallen during this battle.[16]

- ^ The first version narrated the siege of Bahnasa were led by Khalid ibn al-Walid, who also brought an ex Sassanid Marzban and his 2,000 Persian convert soldiers in this campaign. The Persian Marzban suggested to Khalid to form a suicide squad who will carry a wooden box filled with mixture of sulphur and oil and placing it at the gates, ignited it and blasting the gates (or melting the iron gate, according to the original translation), allowing the Muslim army to enter the city.[18][19]

- ^ The second version were the Muslim army led by Qays ibn Harith without much details of how the Muslims managed to subdue the city. This source said that Qays ibn Harith name were used temporarily to rename Oxyrhynchus for while to honor his deeds in this campaign, before being renamed to be al-Bahnasa.[20]

- ^ The nobility of the Nomad Arabs were based on tribal militaristic meritocracy and genealogical (both their own and their horses') supremacy, according to Elizabeth E. Bacon[28]

- ^ Alofs's claims were based from medieval sources such as Strategikon, History of Tabari, and others.[29]

- ^ Baghawi transmit the long narrative chains which came from Dhiraar himself which recorded by Al-Tabarani. however Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani rejected the authenticity of the dialogue contained in the narration, although he did not criticize regarding the case that Dhiraar's possession of thousand camels which came in the background of the dialogue narration[86]

- ^ The nobility of the Nomad Arabs were based on tribal militaristic meritocracy and genealogical (both their own and their horses') supremacy, according to Elizabeth E. Bacon[28]

- ^ The derived narrations from Amr ibn al As seems original text from him which preserved by Ibn Abd al-Hakam chains of narrator source[99]

- ^ Professor Ross Burns stated in his book, Damascus, A History, that the arduous march of Khalid from Iraq to Syria lasted eighteen days, not six days, as the other historians mentioned.[104]

- ^ The derived narrations from Amr ibn al As were attributed to the traditions of Ibn Abd al-Hakam chains of narrators[99]

- ^ "People of the lance" as quoted by Elizabeth E. Bacon[123]

- ^ The hadith were included in record of Ibn Manzur record of Miqdad ibn Aswad biography in his book, brief history of Damascus[173]

- ^ Transmitted by Al-Daraqutni were observed and discussed by contemporary scholars of Islam particularly Salafist for the ruling from Umar were naturally relevant with Al-Anfal verse 41 "And know that anything you obtain of war booty - then indeed, for Allah is one fifth of it and for the Messenger and for [his] near relatives;"[Quran 8:41 (Translated by Saheeh International)], as the modern salafist borrowed the interpretation of the verse from Ibn Kathir and Al-Baghawi, that Zubayr privilege were valid as he still counted as blood relative of Muhammad through az-Zubayr mother, so aside from the three parts which usually given to cavalry, two more parts of spoils were given to Zubayr for his blood relation with the prophet.[174]

- ^ The egalitarian Kharijite doctrine brought by the Sufrite preachers were indeed also found homage to the flocks of Berber soldiers due to their largely unequal treatment under caliphate[176]

- ^ These faction according to Akbar Shah were groups that living peacefully in the soils of Iran province, who became awake and active after the decline of Abdullah ibn Zubayr power and the provocation of the Umayyad propagandists in Iran against Abdullah ibn Zubayr.[178]

- ^ Abu Bilal Mirdas were known by Muslim historians during one of the sermon by Abdallah ibn Amir, Amir or governor of Iraq, Abu Bilal openly criticizing the governor for his garment: "Look at our Amir wearing clothes of wickedness!", this prompted So Abu Bakrah Muhammad ibn Bashar Bindar, a Tabi'un, angrily reprimand Abu Bilal by saying: "Be quiet! I heard the Messenger of Allah saying: "Whoever insults Allah's Sultan on the earth, Allah disgraces him."[179][180]

- ^ Sunni Muslim scholars agreed that Yazidiyyah and Maimuniyyah were the most deviant among all Kharijite sects according to Islamic Iman doctrine, as they have further different concept of prophet in Islam and Qur'an. Thus, according to Prof. Dr. Muhammad Isa al-Hariri were the reasons the jurists and scholars of Islam to brand the Yazidiyyah and Maimuniyyah as true Kafir (Heretic in Islam)[187]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Akram 2006, p. 359-417.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ali 2018.

- ^ Kremer & Bukhsh 2000, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e Kucera 2013.

- ^ a b c Schiettecatte & Zouache 2017, p. 51-59.

- ^ a b Bennett, Conquerors, p. 130

- ^ a b c "The Arabian Horse: At War". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Hüseyin GÖKALP (2021). "The Life of the Prophet in Terms of Battles and Expeditions". Siyer Araştırmaları Dergisi (11): 78; Terzi, 73. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b Akram 2017.

- ^ a b Tabari: Vol. 3, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Safiuz Zaman 2015.

- ^ Werner Daum; Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde München (1987). Yemen 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix (Architecture -- Yemen). Penguin Book Australia. p. 15. ISBN 9783701622924. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ a b Maḥmūd Shākir (1983). Maydan màrakat al-Yarmuk (Islamic Empire -- History, Yarmūk river, Battle of, 639) (in Arabic). Dār al-Ḥarmīn. p. 37. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Norris 1986, p. 81.

- ^ Hendrickx 2012, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c d e "دفن بها 5 آلاف صحابي.. البهنسا قبلة الزائرين من كل حدب وصوب". Gulf News. Gulf News. 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Abdul Ghafur, Hassan (2020). ""البهنسا" البقيع الثانى بالمنيا.. هنا يرقد أبطال غزوة بدر.. دفن بأرضها نحو 5000 صحابى.. وبها مقام سيدى على التكرورى.. السياحة ترصد ميزانية لأعمال ترميم وصيانة آثارها وأبرزها قباب الصحابة وسط مدافن البسطاء (صور)". al-Yaum al-Sab'a. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Waqidi, Muhammad ibn Umar. "Futuh Sham, complete second version". modern comprehensive library. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Waqidi, Muhammad ibn Umar (2008). فتوح الشام (نسخة منقحة) (Revised ed.). p. 48. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Al Shinnawy, Mohammed (2019). "مدينة الشهداء خارج حساب محافظ المنيا" [The city of martyrs is outside the account of the governor of Minya]. Shada al-'Arab. Shada al-'Arab. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Kenney 2006, p. 26.

- ^ a b Timani 2008, p. 09.

- ^ a b Donner 2014, p. 196,197,342

- ^ a b Kenney (2006), p. 41, calls him "the first ‘Kharijite’ caliph".

- ^ a b al Hussein & Culbertson (2010, p. 22)

- ^ a b Hyland 1994, p. 55-57.

- ^ a b c d e Mubarakpuri 2005.

- ^ a b Bacon 1954, p. 44;.

- ^ Alofs 2015, volume 22, pp. 4–27.

- ^ a b Muhammad Al-Harafi, Salamah (2011). Buku Pintar Sejarah & Peradaban Islam (ebook) (in Indonesian) (first ed.). Cairo, Egypt; Cipinang Muara, East Jakarta, Indonesia: Maktabah ad Diniyyahl; Pustaka al-Kautsar. pp. 544–545. ISBN 9789795927532. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ A. Gabriel, Richard (2014). "Arab warfare". Muhammad: Islam's First Great General (Biography, Autobiography). University of Oklahoma Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780806182506. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

By the Roman and Persian periods the typical Arab sword had become a long straight heavy weapon made of iron.20 By Muhammad's day these clumsy weapons had ...

- ^ a b Jam'a, Husayn. "عمرو بن معد يكرب" [Amr ibn Ma'di-Yakrib]. Arabic Encyclopedia (in Arabic). Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- Abu Al-Faraj Al-Isfahani, Al-Aghani (The Heritage Revival House, Beirut, d.T). - Ibn Qutayba, Poetry and Poets, investigated by Ahmed Muhammad Shaker (Dar Al Maaref, Egypt 1966 AD). - Amr bin Maadi Karb, his poetry, collected by Al-Tarabishi (The Arabic Language Academy, Damascus 1985). - Omar Farroukh, History of Arabic Literature (Dar Al-Ilm for Millions, Beirut, 1978).

- ^ Q. Fatimi, S. (1964). "Malaysian Weapons in Arabic Literature: A Glimpse of Early Trade in the Indian Ocean". Islamic Studies. 3 (2). Science of Religion, Index Islamicus, Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS), Internationale Bibliographie der Rezensionen (IBR), Muslim World Book Review, Middle East Journal, ATLA Religion Database, Religion Index One (RIO) and Index to Book Reviews in Religion (IBRR).: 212–214. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20832742. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Tabari 1992, p. 105.

- ^ Alofs 2015, pp. 1–24.

- ^ a b c d R. Hill, D. (1963). The mobility of the Arab armies in the early conquests. Durham E-Theses (theses). Durham University. pp. 20–240. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e al-Mubarak 1997, p. 31-34.

- ^ Alofs 2014, pp. 429–430.

- ^ ibn al-Athir, Ali; Al-Jazari, Ali Bin Abi Al-Karam Muhammad Bin Muhammad Bin Abdul-Karim Bin Abdul-Wahed Al-Shaibani (1994). "Sa;d ibn Abi Waqqas". Usd al-ghabah fi marifat al-Saḥabah (in Arabic). Dar al-Kotob Ilmiya. Retrieved 28 November 2021.Riyadh ibn Badr al-Bajrey (2019). kajian Sahabat Nabi: Sa'ad bin Abi Waqqash; commentary of companion of the prophet: Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas (in Indonesian and Arabic). Bali.

- ^ Masih 2019.

- ^ a b Mohammed 2019, p. 13-21.

- ^ Mayer 1943, p. 2-4.

- ^ Al-Khudair 2015.

- ^ Abdul-jabbar 2013, p. 370.

- ^ Mayer 1943, p. 2.

- ^ Faizer 2013, p. 231

- ^ a b Shahîd 1995, p. 576.

- ^ Shahîd 1995, p. Appendix II.

- ^ a b c Alofs 2014, pp. 430–443.

- ^ De Slane 1868, p. 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicolle (2017)

- ^ Ogden (2018)

- ^ a b c d e Olsen et al. (2020)

- ^ a b Elwyn Hartley Edwards (1987). Horses Their Role in the History of Man (hardcover) (Horses -- History, Horses -- History -- Social aspects). Willow books. pp. 29, 72. ISBN 978-0-00-218216-4. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Stepanov et al. (2020)

- ^ Schiettecatte & Zouache 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Hathaway 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Flag. Britannica. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Hinds 1996, p. 133.

- ^ Nicolle 2017, p. 6.

- ^ Hinds 1996, p. 108.

- ^ Nour, “L’Histoire du croissant,” p. 66/295. See also Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, pp. 214–15.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 533.

- ^ Hathaway 2003, p. 95-6.

- ^ Hüseyin GÖKALP 2021, p. 81; Prepare against them what you ˹believers˺ can of ˹military˺ power and cavalry to deter Allah's enemies and your enemies as well as other enemies unknown to you but known to Allah. Whatever you spend in the cause of Allah will be paid to you in full and you will not be wronged. al-Anfal, 8/60..

- ^ a b al-Mubarak 1997, p. 31.

- ^ a b Ibn Hisham 2019, p. 583.

- ^ Ibn Kathir (2012). Amin Qalaji, Dr., Abdul Muti (ed.). جامع المسانيد والسنن الهادي لأقوم سنن 1-18 ج10 [Jami` Al-Masanid and Al-Sunan Al-Hadi to Establish Sunan 1-18 Part 10] (eligion / Islam / General) (in Arabic). Lebanon: Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية. p. 5368. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

مُسْنَدِ عُمَرَ بْنِ الْخَطَّابِ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ 2 Musnad `Umar b. al-Khattab narrated by Simak; Grade:Lts isnad is Hasan] (Darussalam) Reference: Musnad Ahmad 344 In-book reference : Book 2, Hadith 250

- ^ bin Husain Abu Lauz 2004

- ^ Alofs 2015, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Nicolle 2017, p. 36.

- ^ Alofs 2015, p. 22-24.

- ^ Hardy, James (2016). "Battle of Yarmouk: An Analysis of Byzantine Military Failure". History Coperative. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

In addition, the Arab army was able to use their foot and cavalry archers to great effect, placing them in prepared positions, and were thus able to halt the initial Byzantine advance, John Haldon, Warfare, State, and Society in the Byzantine World: 565-1204. Warfare and History. (London: University College London Press, 1999), 215-216; The skill of the Arab cavalry, particularly the horse archers, also gave the Arab army a distinct advantage in terms of their ability to outmaneuver their Byzantine counterparts. The delay between May and August was disastrous for two reasons; first it provided the Arabs with an invaluable respite to regroup and gather reinforcements. Second, the delay wreaked havoc on the overall moral and discipline of the Byzantine troops; the Armenian contingents in particular grew increasingly agitated and mutinous, Jenkins, Romilly. Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries AD 610-1071. Medieval Academy Reprints for Teaching. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987. p 33

- ^ Francis Lepree, James; Djukic, Ljudmila (2019). The Byzantine Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes] (PhD.). ABC-CLIO. p. 70. ISBN 978-1440851476. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Tabari, Ibn Jarir (1989). K. A. Howard, I. (ed.). The Conquest of Iraq, Southwestern Persia, and Egypt (hardcover). SUNY Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 9780887068768.

- ^ a b c d e Petersen 2013, p. 435.

- ^ a b Biladuri 2011, p. 216.

- ^ Ghadanfar 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Maqbul Ahmed; A. Z. Iskandar (2001). Y. al-Hassan, Ahmad (ed.). Science and Technology in Islam: Technology and applied sciences (hardcover) (Islam and science, Medicine -- History -- Islamic countries, Science -- History -- Islamic countries, Technology -- History -- Islamic countries, Arabic language, Arabic literature -- History and criticism, Historiography -- Islamic countries, Islam -- History -- Social aspects, Islam -- Social aspects, Islam and culture, Islam and state, Islamic arts, Islamic civilization, Islamic countries -- Civilization -- History, Islamic learning and scholarship, Islamic philosophy, Islamic sociology, World history). UNESCO Pub. p. 250. ISBN 9789231038310. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Ibn Abd Rabbih; Roger Allen; Terri DeYoung; Centre for Muslim Contribution to Civilization (2006). Allen, Roger (ed.). The Unique Necklace Volume 1 (hardcover) (Arabic language -- Versification, Civilization, Islamic -- Sources -- History, Islamic civilization -- Sources -- History, Arabic literature -- Translations into English -- 750-1258, History, Islamic civilization in literature). Translated by Issa J. Boullata. Garnet Pub. ISBN 9781859641835. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Schiettecatte & Zouache 2017, p. Uerpmann & Uerpmann, 2013, p. 199‑200; Yule et al., 2007, p. 505..

- ^ Al-Dabba, Mahmud (2021). "أبرزهم "السرحان".. تعرف على 16 اسم لخيول الصحابي خالد بن الوليد" [The most prominent of them is “Al-Sarhan” .. Learn 16 names for the horses of the Companion Khaled bin Al-Waleed]. Alkonouz. Alkonouz Arab world horse community site. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

The horses of Khalid ibn al-Walid were named huzuma, al bahrah, Sabhah, Sabqa. al-Masrat, wakil, Za'jat. al-'Anaq. as-Sarhan, dawma. Lamaa'. Masnuun. al-'Alawiyya. al-Haq, and Hirm

- ^ Q. Fatimi, S. (1964). "Malaysian Weapons in Arabic Literature: A Glimpse of Early Trade in the Indian Ocean". Islamic Studies. 3 (2). Science of Religion, Index Islamicus, Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS), Internationale Bibliographie der Rezensionen (IBR), Muslim World Book Review, Middle East Journal, ATLA Religion Database, Religion Index One (RIO) and Index to Book Reviews in Religion (IBRR).: 212–214. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20832742. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ a b Lewis 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Lewis 1970, p. 222.

- ^ al-Asqalani, Ibn Hajar. sc "Dhiraar ibn Azwar". Hawramani. Ikram Hawramani. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Ibn Umar al-Waqidi, Muhammad. "Futuh al-Sham (Revised Version) chapter:ذكر وقعة اليرموك". al-eman.com. al-eman. pp. 21–49. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "الخيل في الغارات والحروب" [Horses in raids and wars] (in Arabic). Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Cosgrove et al. 2020, p. 1–13.

- ^ Upton 2006.

- ^ Archer, Rosemary (1992). The Arabian Horse. Allen Breed Series. London: J. A. Allen. ISBN 978-0-85131-549-2.

- ^ Arabian Horse Association. "Arabian Type, Color and Conformation". FAQ. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Tabari 2015, p. 61.

- ^ Ibn Hisham, Abu Muhammad 'Abd al-Malik. "Sirat Ibn Hisham: The names of Muslim horses on the day of Badr". Islam web. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b Ibn al-Kalbi (2003, p. 35)

- ^ a b ʻAbd Allāh ibn ʻAbd al-Muḥsin ibn Manṣūr Ṭurayqī (1997). أهلية الولايات السلطانية في الفقه الإسلامي (Caliphate, Executive power (Islamic law), Islam and state, Islamic law) (in Arabic). يطلب من مؤسسة الجريسي للتوزيع. p. 100, When 'Umar b. al-Khattab sent out his governors he laid on them the condition that they should not ride a horse not of Arabian breed,* or eat white bread, or wear fine clothing, or shut their gates against the needs of the people, telling them that if they did any of these things punishment would befall them. Then he would accompany them some distance. Baihaqi transmitted in Shuab al iman. * Birdhaun. This word is used of a horse of poor breed, a horse not of Arab breed, or more specifically a Turkish horse. It is suggested that the reason for the wording is to warn governors against riding horses, this being a sign of pride. Prohibiting a breed considered second-rate makes it obvious that to ride horses of the best Arab breed would be even a greater sign of pride. ISBN 9789960275116. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

18 The Offices of Commander and Qadi (1c) Chapter: The Duty of Rulers to make Things Easy - Section 3; Mishkat al-Masabih 3730 In-book reference : Book 18, Hadith 69

- ^ a b c d e f g Schiettecatte & Zouache 2017

- ^ a b c d Abd al-Baqi al-Balaa (2016). "الخيل في المعارك .. الأفراس مرغوبة والجياد مطلوبة" [Horses in battle.. Mares are desirable, and horses are wanted]. Alassalah (in Arabic). Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ibn Abd al-Hakam 1922.

- ^ al-Bukhari, Muhammad. "Sahih al-Bukhari 3975; Urwah ibn Zubayr narration; deemed Authentic by Bukhari". Amrayn.com. © 2014–2021 Amrayn.com. p. 313, Urwah ibn Zubayr reported: On the day of (the battle) of Al-Yarmuk, the companions of Allah's Apostle ﷺ said to Az-Zubair, Will you attack the enemy so that we shall attack them with you?. Az-Zubair replied, If I attack them, you people would not support me.; They said: No, we will support you.; So Az-Zubair attacked them (i.e. Byzantine) and pierced through their lines, and went beyond them and none of his companions was with him. Then he returned and the enemy got hold of the bridle of his (horse) and struck him two blows (with the sword) on his shoulder. Between these two wounds there was a scar caused by a blow, he had received on the day of Badr (battle). When I was a child I used to play with those scars by putting my fingers in them. On that day (my brother) Abdullah bin Az-Zubair was also with him and he was ten years old. Az-Zubair had carried him on a horse and let him to the care of some men. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Abu Bakr 1985, p. 249, It was narrated by Abdullah ibn Zubayr, his son who witnessed his father praying while fought at the sametime on the top of his camel

- ^ Lydon 2009, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Davis 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Burns 2007, p. 99.

- ^ le Strange, 1890, p. 395

- ^ Akram 2006, p. 275-279.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Gil 1997, pp. 47–48, note 50.

- ^ Vaglieri 1965, p. 625.

- ^ Nafziger & Walton 2003.

- ^ Tabari 2015, p. 50.

- ^ a b Idllalène 2021, p. 51; See Llewellyn; The basis for a Discipline of Islamic environmentally law; page.212.

- ^ Aḥmad ibn Yaḥyá Balādhurī; Philip Khuri Hitti; Francis Clark Murgotten (1916). The Origins of the Islamic State, Being a Translation from the Arabic, Accompanied with Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitâb Fitûh Al-buldân of Al-Imâm Abu-l Abbâs Ahmad Ibn-Jâbir Al-Balâdhuri Issue 163, Part 1 (Economics, History, Islamic Empire, Muslims, Social sciences). University of Minnesota. p. 23. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Q. Ahmed 2011, pp. 30–49

- ^ Idllalène 2021, p. 51; see Gary Lutfallah; A History of Hima Conservation system; 2006.

- ^ Caskel 1960, p. 441.

- ^ Krenkow 1993, p. 1005.

- ^ Shahîd 2002, pp. 57–68.

- ^ A ḥima (pl. aḥmāʾ; protected or forbidden place) was an area with some vegetation in the desert reserved for the breeding of Arabian horses, that unlike camels, required water and herbaceous vegetation daily. A ḥima was controlled by a certain tribe and access to it was restricted to members of the tribe. The aḥmāʾ first emerged in Najd in the 5th or 6th centuries, and the best known ḥima was the Ḥima Ḍarīyya, according to the historian Irfan Shahîd.[118]

- ^ Al-Rashid 1979, pp. 88–89 Primary sources from Abu Ali al-Hajari's book compilations (3rd AH), Abu Ubaid al-Bakri book: Mu'jam M Ista'jam (5th AH), Al-Samhudi's book Wafa' al-Wafa' bi Akhbar Dar al-Mustafa (6th AH)

- ^ a b Al-Rashid 1979, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Christine Helms (2020). "The Ikhwan". The Cohesion of Saudi Arabia (RLE Saudi Arabia) Evolution of Political Identity (ebook) (Business & Economics / Government & Business, Political Science / General, Social Science / Regional Studies). Taylor & Francis. p. 149. ISBN 9781000112931. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ a b Bacon 1954, p. 44.

- ^ Hutton & Bagehot 1858, p. 438; Kabail, Nomadic, pastoral; Quoting Pultzky book page 386.

- ^ Greene, Stager & Coogan 2018, p. 371 Quoting Richard Bulliet

- ^ a b Khazanov & Wink 2012, p. 225.

- ^ a b Greely, Margareth (1975). Arabian Exodus. J. A. Allen. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-85131-223-1. Retrieved 26 November 2021.