Republic of Singapore Navy

| Republic of Singapore Navy | |

|---|---|

| Angkatan Laut Republik Singapura (Malay) 新加坡海军部队 (Chinese) சிங்கப்பூர் கடல் படை (Tamil) | |

Crest of the Republic of Singapore Navy | |

| Founded | 5 May 1967 |

| Country | |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Naval warfare |

| Size | 4,000 active personnel[1] 5,000 reserve personnel[1] 40 ships |

| Part of | Singapore Armed Forces |

| Garrison/HQ | Changi Naval Base |

| Motto(s) | "Beyond Horizons" |

| March | "Republic of Singapore Navy March" |

| Ships |

|

| Engagements | |

| Website | Official website |

| Commanders | |

| President of Singapore | Tharman Shanmugaratnam |

| Minister for Defence | Ng Eng Hen[3] |

| Chief of Defence Force | VADM Aaron Beng[3] |

| Chief of Navy | RADM Sean Wat[3] |

| Master Chief Navy | ME6 Richard Goh[3] |

| Insignia | |

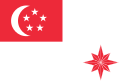

| Pennant | |

| Ensign |  |

| Jack |  |

| State Colour |  |

| Logo |  |

The Republic of Singapore Navy (RSN) is the maritime service branch of the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) responsible for defending the country against any seaborne threats and as a guarantor of its sea lines of communications. The RSN traces its origins to the Royal Navy when Singapore was still a crown colony of the British Empire. The service was formally established in 1967, two years after its independence from Malaysia in 1965, and had undergone a substantial modernisation ever since – which has led them into becoming the most powerful navy in Southeast Asia.[4][5][6]

The RSN also regularly conducts operations with the navies of its neighbouring countries to combat piracy and terrorist threats in the congested littoral waters of the Strait of Malacca and Singapore.[7][8] It also jointly operates the Fokker 50 maritime patrol aircraft with its counterparts from the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) to provide air surveillance of the seaward approaches to Singapore, which is one of the busiest sealanes in the world.[9][10] The RSN has engaged in international anti-piracy operations further abroad, partaking in the multinational Combined Task Force 151 off the Gulf of Aden.

Though numerically small in comparison to its much larger neighbours in terms of tonnage and manpower reserves, the RSN counteracts by continuously seeking to maintain a qualitative superiority over any adversary through the implementation of new technologies, fostering of alliances with extra-regional navies, and increased reliance on automation and unmanned assets.[11] This has made the RSN one of the most sophisticated and well trained navies in the region. In addition, bilateral exercises with foreign navies are also held regularly.[12][13]

All commissioned ships of the RSN have the ship prefix RSS standing for Republic of Singapore Ship.

Mission

[edit]The economy and defence are closely interlinked... We need the sea lanes to Singapore to be opened; hence a capable navy is crucial.

— Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew[14]

As an island nation, the RSN forms part of Singapore's first line of defence. Its stated mission objectives are to:[15]

- Protect Singapore's sealine of communications and contribute to regional peace and security.

- Maintain continuous surveillance on the Singapore Strait to prevent sea robberies, piracy, terrorism and unwanted incursions during peacetime.

- Work to secure a swift and decisive victory over any enemy at sea during war.

- Conduct diplomacy by exercising with foreign navies and taking part in international operations for peace support, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

History

[edit]Colonial and pre-independence era

[edit]

The Republic of Singapore Navy traces its origins to the Royal Navy in the 1930s with only two patrol craft. The Straits Settlements Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (SSRNVR) was established on 27 April 1934, and in 1941 became the Singaporean division of the Malayan Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (MRNVR) during World War II.[16] The service received several 75' motor launches built locally by John I. Thornycroft & Company Shipyard in Tanjong Rhu: HMS Pahlawan and the first HMS Panglima in 1937; the latter would later be sunk during the fall of Singapore in February 1942. A new 90' motor vessel bearing the name Panglima was launched in 1944, but upon its transfer to the MRNVR in 1948, proved unsuited for tropical waters and began deteriorating rapidly.[17]

In 1948, the Malayan Force was raised by the Singaporean government, and was later granted the title of the Royal Malayan Navy in 1952 in recognition of its services in action during the Malayan Emergency. The third and final Panglima was launched in January 1956 to replace the second vessel. Being more technologically advanced than her predecessors, she became an indispensable part of the local fleet.[17]

On 16 September 1963, Singapore was admitted as a state of Malaysia under the terms of confederation and the Royal Malayan Navy was renamed the Royal Malaysian Navy. The Singapore division of the MRNVR was formally transferred from the command of the Royal Navy to the Royal Malaysian Navy on 22 September 1963, becoming the Singapore Volunteer Force.[16] During the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, Singapore-based ships were charged with defending the southern border against infiltrators and saboteurs, and also undertook local minor engagements against the Indonesian Navy.[12]

Independence of Singapore

[edit]On 9 August 1965, Singapore seceded from Malaysia to form an independent republic inside the Commonwealth. The SVF became the de facto naval force of the new state, though it remained under the command of the Royal Malaysian Navy. Three ships remained in Singapore after separation: KD Singapura, a captured Japanese minelayer; KD Bedok, a patrol boat from Malaysia; and KD Panglima, the former Royal Navy inshore patrol boat built in 1956.[a] Panglima was recommissioned as a Singaporean ship on 1 January 1966.[20] On 1 February, the service ceased to be under Malaysia and became the Singapore Naval Volunteer Force (SNVF); Bedok and Singapura were also recommissioned and the latter became a floating headquarters.[17][21]

Now that the new white ensign of our own young country will fly here and in our ships, I hope that you will all remember that its reputation is in your hands.

— Executive Officer Jaswant Singh Gill inaugurating the SNVF on 5 May 1967 at the Telok Ayer Basin[22]

A new naval ensign was hoisted at the Telok Ayer Basin for the first time on 5 May 1967 and is marked as the day of the Navy's official establishment.[b] In September, the service was renamed the People's Defence Force – Sea and placed under the Sea Defence Command, with the command being thereafter renamed the Maritime Command in December.[24][25] The name changes reflected the internal restructuring within the Singapore Armed Forces and the growing realisation that maritime security was a crucial element to national security.[26] Headquarters was shifted ashore to Pulau Belakang Mati in 1968.[27] In order to develop local expertise in seamanship and naval engineering, 160 naval recruits underwent training by Royal New Zealand Navy instructors in 1969. At the same time, aspiring officers were sent overseas to learn from established navies in Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand.[28]

The Maritime Command launched an expansion program with the objectives of combating sea robberies and smuggling, and improving seaward power projection. In June 1968, six Independence-class patrol crafts were purchased and commissioned between 1970 and 1972, marking the first purpose-built ships the Navy possessed. Part of the urgency stemmed from British prime minister Harold Wilson's intention to withdraw British troops East of Suez by 1971, which would leave a security vacuum, though a smaller British presence eventually remained under the Five Power Defence Arrangements.[29] Growing constraints and strategic need for a base located nearer to the strait was solved by the opening of Brani Naval Base in December 1974.[28] The foresight was validated a few weeks later when terrorists from the Japanese Red Army attacked an oil complex on Pulau Bukom and hijacked the Laju ferry. Four vessels, RSS Sea Hawk, RSS Independence, RSS Sovereignty and RSS Daring together with the Marine Police, were able to surround the fleeing ferry and prevent it from escaping.[28]

Colonel James Aeria would be the final commander of the Maritime Command.[30][31] On 1 April 1975, the Maritime Command was renamed the Republic of Singapore Navy as part of the reorganisation of the Singapore Armed Forces into three distinct services, and has kept the name ever since.[32]

Fleet modernisation

[edit]

The RSN was the first navy in the region to successfully fire a live anti-ship missile when RSS Sea Wolf fired two Gabriel missiles in March 1974.[33][34] From 1975 to 1976, six Sea Wolf-class missile gunboats were commissioned, which proved vital during Operation Thunderstorm when they were deployed to patrol and apprehend the influx of boat people fleeing the fall of South Vietnam. In order to support sealift operations, six County-class tank landing ships were purchased from the United States; these were popularly referred to as dollars ships due to the price ($1) paid for each vessel. Two Bluebird-class minesweepers were also transferred from the United States to combat the threat of mine warfare within the narrow and shallow channels of the Singapore Strait.[12][35] Prior to this, the SAF Diving Center had already been established in 1971 to train the first batch of frogman recruits in conducting underwater mine disposal operations.[36] In 1975, the service was reformed as the Naval Diving Unit and based at Sembawang Camp, where it remains.[28]

During the latter half of the decade, the increased operational demands and rate of patrols led the Navy to seek three additional missile gunboats and an upgrade to the Harpoon missile for the existing fleet under Project Albatross. Due to budgetary constraints in the early 1980s, Defence Minister Howe Yoon Chong decided to allocate more funds to the Air Force for the acquisition of a squadron of F-16s; the fighter jets were deemed to possess a higher strategic strike value and capable of more diverse roles compared to ships. Howe claimed the Navy's function was best relegated to coastal defence and suggested mounting Oerlikon guns on towed barges as a replacement to guard the nation's maritime borders.[12] Nevertheless, the reduced budget was still sufficient to commission twelve Swift-class coastal patrol craft which freed the missile gunboats from daily patrols for more strategic operations.[37][38]

With the Navy being the lowest priority among the three services, it saw little hope of an expanded fleet with a larger stake in Singapore's defence and many people left the service. This created a "crisis of confidence" within the RSN in the next few years, which defence planners regarded as lacking a proper doctrine for existence beyond patrols and tackling illegal immigration. It was not until 1984 that naval officials convinced the government of the necessity of a seagoing fleet to secure the nation's sea lines of communication in the Malacca Strait and South China Sea, both of which lead to the Port of Singapore; a major contributor to the economy.[12] To combat the growing technological obsolescence and decline in morale, the government launched the "Navy 2000" program. The service underwent an internal restructuring with the formation of the Coastal Command (COSCOM) in 1988 and the Fleet in 1989, formalising the responsibilities of each class of ship.[39] Between 1990 and 2001, the resurgent navy acquired six Victory-class missile corvettes, twelve Fearless-class patrol vessels, four Endurance-class landing ship tanks and also commissioned four secondhand Challenger-class submarines from Sweden to hone its underwater domain skills.[12]

In 1979, Malaysia published a map laying claim to Pedra Branca, an offshore island controlled by Singapore. The resultant Pedra Branca dispute lasted 29 years until 2008 when the island was awarded to Singapore by the International Court of Justice, during which the Navy was heavily involved in patrols and maintained an active presence in the waters surrounding the island.[40] In January 2003, RSS Courageous collided with a merchant vessel within the vicinity of Pedra Branca during a patrol, resulting in four casualties and the first ship to be stricken as a total loss.[41] As a result of the accident, additional safety measures were implemented and the training program enhanced, including the requirement for all officers to better understand the manoeuvring characteristics of their ship and take a COLREGs test every six months.[42]

The RSN had also participated in operations other than war within Southeast Asia and abroad. The Navy deployed its Bedok-class mine-countermeasure vessels to search the Musi River for SilkAir Flight 185; served as part of the Australian-led International Force East Timor to address the humanitarian and security crisis in the aftermath of the territory's referendum for independence in 1999; deployed three ships to provide humanitarian assistance and emergency aid to the Indonesian town of Meulaboh in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake;[43][44] and was part of the Multi-National Force – Iraq coalition force maintaining maritime security around key Iraqi installations in the Persian Gulf.[34][45]

Evolving security challenges

[edit]

The Coastal Command was revamped in 2009 into the Maritime Security Task Force to improve coordination between national maritime agencies such as the Police Coast Guard and harbour authorities. Between 2007 and 2020, the RSN has introduced new Archer-class submarines, Formidable-class frigates and Independence-class littoral mission vessels to its fleet to enhance its deterrence amidst rising tensions in the surrounding seas. Unmanned assets such as the Specialised Marine Craft patrol boat and Protector USV have been commissioned to combat the personnel shortfall in Singapore due to falling birthrates.[46][47]

The RSN has engaged in multilateral anti-piracy operations in the Malacca Strait with neighbouring nations;[48] and in the Gulf of Aden and Horn of Africa under the multinational naval Combined Task Force 151, taking command of the task force thrice;[49][50][51][52] It participated in both the search for MH Flight 370 in the Gulf of Thailand and QZ Flight 8501 in the Karimata Strait in 2014.[53][54][55] In an analysis of the SAF humanitarian response to Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen noted that the disruption of communications on the ground underscored the need for a platform which could provide "centralised ability for command and control" in the air.[56]

The RSN celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2017 and hosted an international fleet review, with twenty nations participating.[23]

In October 2018, Malaysia extended its Johor Bahru port limits past its 1979 maritime claims into waters off the reclaimed Tuas sector which Singapore claims as its own. Singapore responded by extending its port limits to overlap with Malaysia's new port limits. As Malaysia deployed elements of the Malaysia Coast Guard and government ships to enforce their claims, the RSN's littoral mission vessels were stationed on location 24/7 with the Police Coast Guard.[57] Both side eventually suspended the overlapping port limits and withdrew from the area following successful negotiations.[58][59]

The Navy underwent a comprehensive restructuring in June 2020 which dissolved all the existing squadrons, reorganising each class of ship into its separate flotilla. The Maritime Security Task Force was restructured, with the newly created Sea Security Group and Force Protection Group placed under it.[60]

Future procurement plans

[edit]The RSN launched its first newly built Invincible-class submarine in 2019, with the second and third submarines RSS Impeccable and RSS Illustrious launched on 13 December 2022. All three submarines will be expected to be commissioned in 2023, with an operationalisation date set for 2024.[61] The fourth submarine RSS Inimitable remains in construction, together with a fifth, previously undisclosed, submarine.[62]

Contract for the procurement for six multi-role combat vessels (MRCV) was signed between ST Engineering Marine Ltd and SAAB on 28 March 2023[63] while procurements plans for the drone-laden Joint Multi-Mission Ships (JMSS) are ongoing. The MRCVs will act as a 'mothership' for unmanned assets and host mine-countermeasure Venus-16 USVs,[52] while the JMSS will increase the RSN's aviation capabilities in supporting disaster relief operations.[64][65] A new class of patrol vessels to operate alongside the existing littoral mission vessels are to enter service in 2026.[66][67]

Organisation

[edit]

Command structure

[edit]The Republic of Singapore Navy is led by the Chief of Navy (CNV), who reports directly to the Chief of Defence Force (CDF). The CNV is responsible for the RSN's overall operational capabilities and administration. The organisational chart shows the peacetime administrative chain of command with five formations: the Fleet, Maritime Security Command, Naval Logistics Command, Naval Diving Unit, and the Maritime Training and Doctrine Command.[68][69]

The current Chief of Navy is Rear Admiral Sean Wat, who took over command on 10 March 2023.[70]

Operating forces

[edit]The Fleet is responsible for operations beyond the Singapore Strait and represents the main strike arm of the navy. Its frigates and missile corvettes are capable of conducting anti-surface, anti-air and anti-submarine operations with their equipped armaments and sensors. Its landing ships tank and civil resource vessels provide sea transportation and logistics support overseas, while the submarines force provides a subsurface capability for the navy.[69]

The Maritime Security Task Force (MSTF) is a SAF-level standing task force formed after the restructuring of Coastal Command.[60][71] Its role is to ensure Singapore's maritime security and act as a co-ordinating agency for all national maritime agencies to allow for the seamless execution of maritime security operations.

The Naval Diving Unit is charged with "explosive ordnance disposal, underwater mine demolition and commando-type missions". Its personnel are considered among the elite forces of Singapore.[69][72]

Logistics

[edit]The Naval Engineering and Logistics Command (NELCOM) is responsible for up-keeping and planning the maintenance schedules of ships and the equipping of supplies and assets.[73] It also conducts weapons readiness checks on ships and works closely with the Defence Science and Technology Agency and ST Electronics.[69][74]

Training

[edit]As with the army and air force, all officers of the navy are trained and commissioned at the Officer Cadet School with their interservice counterparts. As midshipmen, part of their training involves being deployed four weeks at sea with the regular fleet to hone their skills in leadership, navigation and basic seamanship.[75][76] Navy officers are also offered specialisation courses later in their careers at the Naval Officers' Advanced Schools (NAS) which is part of the SAF Advanced School (SAS). The courses offered are Naval Advanced Officer Course (NAOC), Mine Hunting Officer Course (MHOC), Naval Warfare Officer Course (NWOC) and Command Preparatory Programme (CPP).[77]

Enlisted specialists and regular military experts (ratings) are instructed in their specialised domains at the Naval Military Experts Institute, under the Maritime Training and Doctrine Command (MTDC), based at Changi Naval Base. This training consists of all the key aspects of the duties the sailors are expected to perform on board the ships. This includes basic firefighting and damage control skills, rope handling and seamanship skills as well as shiphandling which is done through a ship simulator allowing trainees to practice their watchkeeping skills inside a safe, controlled environment.[78][79] The enlisted specialists and military experts undergo a rigorous and realistic Summative Exercise (SUMEX) at the end of their course prior to joining the operational ships.

The RSN has also partnered with ST Education and Training to operate the training ship STET Polaris since 2010. Polaris was specially constructed with a "dual bridge" to facilitate training requirements for two navigation teams to operate simultaneously and can carry 30 trainees and instructors;[80][81] the ship was named after the North Star, which mariners had traditionally used as a navigational reference point in ancient times.[82][83]

While submarine training was initially conducted in Sweden by the Royal Swedish Navy, training for submariners are now conducted locally in Singapore. Submariners are trained at the Submarine Training Centre (STC) also known as RSS Challenger, named after the first submarine acquired by the RSN. It is located in Changi Naval Base and is designed to be a state-of-the-art facility featuring submarine simulators in order to enhance the realism and effectiveness of submarine training.[84] Training in the simulators can be up to several days in order to simulate actual deployments when the submariners are training in the STC. Prospective submariners are put through a nine-month-long course which consists of a series of tough tests in order to ensure that every qualified submariner is able to meet operational requirements at sea. The simulators housed in the facility are known as the Submarine Steering and Diving Trainer (SSDT) and Submarine Combat Tactical Trainer (SCTT). The two simulators allow the flotilla to conduct training that closely simulates at-sea conditions without the logistical costs involved in deploying submarines out at sea. The SSDT is designed based on the Archer-class submarine and trains the helmsman to steer the submarine as well as the diving officer in diving the submarine while allowing the “Officer of the Watch” to oversee the entire process. The SCTT is designed to train the submariners in combat operations, which consists of four consoles modelled after those installed on board the actual submarines. These are used to train the crew in submarine combat operations such as analysis, surveillance, command and control, and weapons control.[85] Singapore is also known to have sent prospective submarine Commanding Officers for the Royal Netherlands Navy Submarine Command Course[86] as well as the German Navy Submarine Commanding Officer Course.[87] A training suite for crew members of the new Invincible class submarines is now being developed, which is planned to operationalise by 2024. Like the previous simulators before it, it will consist of the combat trainer as well as diving and steering trainer among others. It will additionally feature a virtual procedural trainer that replicates the submarine with all its more than 12 million parts, that offers both physical and tactile training opportunities for the crew members while ashore.[88]

Enlistees to the Naval Diving Unit are selected based on their eyesight and medical fitness and trained at Frogman School located within Sembawang Camp.[89] Trainees are required to pass a vocational assessment prior to beginning nine weeks of basic military training. Those who qualify then undergo the twenty weeks Combat Diver Course where they are taught dive theory and must qualify for drown proofing, pool competency and survival skills requirements.[90]

Current fleet

[edit]Frigates

[edit]

The Formidable-class multi-role stealth frigates entered service with the RSN in 2007 and are derivatives of the French Navy's La Fayette-class frigate.[91] The frigates are key information nodes and fighting units, and were, at time of launch, "by far the most advanced surface combatants in Southeast Asia"[92] with a special surface-to-air missile configuration which combines the Thales Herakles radar with the Sylver A50 launcher and a mix of MBDA Aster 15 and 30 missiles.[93] Other armaments include Boeing Harpoon missiles and an OTO Melara 76 mm gun for surface defence. The Blue Spear SSM is planned to be equipped onboard the Formidable class Frigates on completion of the mid-life upgrade program.

Equipped with Sikorsky S-70B naval helicopters, an international derivative of the Sikorsky SH-60B Seahawk. These naval helicopters feature anti-surface and anti-submarine combat systems, extending the ship's own surveillance and over-the-horizon targeting and anti-submarine warfare capabilities. The naval helicopters are part of the 123 squadron of the RSAF and piloted by air force pilots.[94] Two more S-70B helicopters were ordered in February 2013.[95]

The lead ship of the class, RSS Formidable was built overseas in Lorient, France and commissioned locally on 5 May 2007, marking the 40th anniversary of the RSN.[96] The final two ships, RSS Stalwart and RSS Supreme were commissioned on 16 January 2009.[97] The six frigates form the First Flotilla of the RSN.

Littoral mission vessels

[edit]

The Independence-class littoral mission vessel is a class of eight surface platforms succeeding the Fearless class. In January 2013, the Ministry of Defence awarded ST Engineering a contract to build and design eight vessels. A subsidiary of the company, ST Marine was charged with building the ships at Benoi Yard and integrating the combat systems supplied by the group's electronics arm, ST Electronics.[98][99] The class was designed with the "lean manning" concept to facilitate a smaller crew complement to reflect the declining birthrate in Singapore, with increased levels of automation and remote monitoring systems.[100] This has resulted in its combat information center, machinery control room, and bridge being co-located in a single location known as the integrated command center.[101] Its modularity also allows the ship to deploy unmanned and mine-countermeasure systems or be reconfigured to support disaster-relief operations.[102] The ships have been sent on overseas deployments.[103][104] The last three ships of the class were commissioned in January 2020.[105]

The littoral mission vessels were formerly under 182 Squadron until June 2020 with the inauguration of the Maritime Security Command. The eight Independence-class littoral mission vessels now form the Second Flotilla of the RSN.[60]

Tank landing ships

[edit]

The Endurance-class tank landing ships are the largest class of ships in the RSN. They were designed and built locally by ST Marine to replace the old County-class tank landing ships (LST). Each ship is fitted with a well dock that can accommodate four landing craft and a flight deck that can accommodate two medium lift helicopters.[106] While the RSN describes the Endurance class as LSTs, they lack the beaching capability traditionally associated with LSTs, and their well docks and flight decks qualify the Endurance class more as amphibious transport docks.

The ships provide sea transportation for personnel and equipment for SAFs overseas training, as well as a training platform for RSN's midshipmen. RSS Endurance became the first RSN ship to circumnavigate the globe when it participated in the 2000 International Naval Review in New York City.[107] The ships are also actively involved in humanitarian and disaster relief operations, notably in East Timor, the Persian Gulf, the tsunami-hit Indonesian province of Aceh and most recently, disappearance of Indonesia AirAsia Flight 8501.[55] The four ships form the Third Flotilla of the RSN.

Mine countermeasures vessels

[edit]

The RSN acquired mine countermeasure capabilities as early as 1975, when the USN's USS Thrasher and USS Whippoorwill were reactivated by the RSN's engineers and technicians in California. The Bluebird-class coastal minesweepers were commissioned as RSS Jupiter and RSS Mercury.[108]

These two ships were eventually replaced by the Bedok-class mine countermeasures vessels. The first ship, RSS Bedok, was built by Karlskronavarvet in Sweden based on the Landsort-class design. The remaining three ships were prefabricated in Sweden and transferred to Singapore for final assembly by ST Marine. The ships are constructed of glass reinforced plastic to maintain low magnetic and acoustic signatures, and are fitted with Voith Schneider Propellers, giving it the highest manoeuvrability in the navy.

The RSN also operates the Protector unmanned surface vehicles. They were deployed together with the Endurance-class landing ships tank to the North Persian Gulf for peacekeeping operations in 2005, where they performed surveillance and reconnaissance, as well as force protection duties for more than eight hours at a go.[109]

Unmanned assets and the mine countermeasures ships form the Sixth Flotilla of the RSN.[110]

Submarines

[edit]Challenger class

[edit]Middle: RSS Swordsman alongside Changi Naval Base

Bottom: RSS Invincible in drydock at the TKMS yard in Germany

In 1995, the RSN acquired a Sjöormen-class submarine from the Swedish Navy and rechristened it the Challenger class. Another three were transferred in 1997, making them Singapore's first underwater platforms.[111] As the submarines were designed for operations in the Baltic Sea, various modifications were required to suit them to tropical waters. A comprehensive tropicalisation refitting programme was implemented for all four submarines, which involved the installation of air conditioning, marine growth protection systems and corrosion-resistant piping.[112]

It was believed that the Challenger class were purchased to develop the required submarine operations expertise before selecting a modern class of submarines to replace them, since all the boats were then over 40 years old.[113] RSS Challenger and RSS Centurion were retired from service in 2015.[114]

Archer class

[edit]The Archer-class submarines were also former Swedish Navy combatants and known as the Västergötland class. In November 2005, an agreement was signed with Kockums for the same tropicalisation modifications for two submarines.[115] Amidst the refitting process, an air independent propulsion system was installed, which necessitated the cutting apart of the submarine's hull to fit new components. RSS Archer was relaunched on 16 June 2009[116] and recommissioned on 2 December 2011, with her sister boat RSS Swordsman being commissioned on 30 April 2013.[117][118] The AIP modification enables the submarines to have longer submerged endurance and lower noise signature, enhancing its stealth capability. The advanced sonar system is capable of detecting contacts at a further distance, while the torpedo system has a better target acquisition capability, which allows the submarines to engage contacts at a further range.

An upgrade program was conducted between 2016 and early 2019, which involved the installation of CM010 optronic periscopes and new combat management, sonar and countermeasure systems.

Invincible class

[edit]The Invincible class, also known as Type 218SG, is a submarine class ordered from Germany's ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems. Two Invincible-class submarines were procured in November 2013 and another two in May 2017.[119][120] Several German industry experts commented then that the project would cost about one billion Euros and take six years to complete, with the first submarine expected to be delivered in 2020.[121]

The diesel electric submarines will have 50 per cent longer endurance, more firepower, more capable sensors and advanced automation than the existing fleet of RSN submarines. Armed with eight torpedo tubes and manned by a crew of 28, they can travel at a surface speed of more than 10 knots and a submerged speed of more than 15 knots. These submarines are particularly customised for Singapore's shallow and busy waters.[122]

The first of four, RSS Invincible, was launched on 18 February 2019. She will undergo sea trials in Germany before delivery in 2022.[123] The second and third boat, RSS Impeccable and RSS Illustrious were launched on 13 December 2022, expected to be delivered in 2023.[124] The remaining one is scheduled to follow by 2024. The Invincible and Archer-class submarines are projected to replace the Challenger-class afterwards.[125]

All submarines, regardless of class, form the Seventh Flotilla of the RSN. The RSN also operates the submarine support and rescue vessel MV Swift Rescue.[126]

Corvettes

[edit]

In 1983, the RSN ordered six Victory-class corvettes from Friedrich Lürssen Werft of Germany, with the first being built in Germany and remaining five locally by ST Marine.[127] The corvettes represented a strategic change in Singapore's defence posture as the Navy sought to redefine its purpose to be "more than a coastguard" and project power in the region for deterrence purposes; they were the first ships in the RSN to have an anti-submarine capability, and remain the fastest ships in the fleet with a speed in excess of 30 knots.[128] A244-S torpedoes were reportedly acquired to counter the threat of an increased number of submarines passing through the Malacca Strait, with Soviet submarines having been tracked passing through entirely submerged.[129] The first three ships were commissioned in August 1990 and the remaining three in May 1991.

The corvettes have been continuously upgraded to incorporate new technologies and better sea keeping capabilities. Two sets of 8-cell Barak I were installed in 1996 as part of a general refit. A life extension program between 2009 and 2013 redesigned the mast to incorporate new sensors, overhauled the combat management system, and added the ability for the ship to launch a single ScanEagle UAV for remote surveillance without the need to approach a target.[130] The anti-submarine torpedoes and variable depth sonar detectors were removed during the refit.[131][132] The six corvettes form the Eighth Flotilla of the RSN.

The Victory-class corvettes are projected to be replaced by six multi-role combat vessels by 2030, with the first ship to be delivered in 2025.[123]

Maritime security and response vessels

[edit]The Sentinel-class maritime security and response vessels (MSRV) are four refurbished Fearless-class patrol vessels. The refurbishment plan was announced in March 2020 in response to the increase of sea robberies within the region, and foreign intrusions of Singapore territorial waters.[133][134] As part of the refit, non-lethal LRAD and laser warning systems were added to increase operational flexibility, while fenders were incorporated into the hull to enable quicker alongside operations of suspicious vessels. The forward part of the bridge was also reinforced with ballistic-resistant armour.[135]

The first two vessels MSRV Sentinel and MSRV Guardian entered operational service on 26 January 2021, with the latter two MSRV Protector and MSRV Bastion on 20 January 2022.[136] Other than the MSRVs, the flotilla will also operate two Maritime Security Tugboats (MSRTs), and will operate new purpose-built vessels from 2026. The ships form the Maritime Security and Response Flotilla of the RSN.[137]

Historical fleet

[edit]Missile gunboats

[edit]

The Sea Wolf-class missile gunboats were acquired in 1968 and based on the TNC 45 design from Fredrich Lürssen Werft.[138] The first two gunboats—RSS Sea Wolf and RSS Sea Lion—were constructed in West Germany in 1972, while the remaining four were constructed locally by Singapore Shipbuilding and Engineering, with all six ships being commissioned by 1976. The gunboats were initially equipped with Israeli-manufactured anti-ship Gabriel missiles and Bofors guns.[139] Sea Wolf fired the first missile by the RSN in March 1972.[33]

As new technology became available, a number of upgrading programmes were initiated to increase their strike capability and sophistication. Between 1986 and 1988, they were upgraded to launch Boeing Harpoon (SSM) surface-to-surface missiles,[140] and in 1994, the Bofors gun was replaced with Mistral surface-to-air (SAM) missiles. The continuous upgrades to the gunboats' armaments and sensors made them regarded as being at the forefront of naval warfare technology between the 1980s and 1990s.[33]

The gunboats engaged in numerous exercises with foreign navies and visited many port of calls throughout their lifespan.[33] On 13 May 2008, all six gunboats were retired at a sunset decommissioning ceremony held at Changi Naval Base following 33 years of service.[141]

Patrol vessels

[edit]

Between the 1970s and 1990s, the RSN operated Independence-class and Swift-class coastal patrol crafts. They were gradually replaced by the Fearless-class patrol vessels built locally by ST Marine to replace the ageing coastal patrol craft, with all ships in commission by August 1989. The first six vessels of the Fearless class were armed for anti-submarine warfare missions and placed under the Fleet as 189 Squadron, with the remaining six being allocated to 182 Squadron under Coastal Command. RSS Courageous was badly damaged in a collision with a container ship in the Singapore Strait in January 2003 and removed from service.[142]

189 Squadron was subsequently transferred to Coastal Command in January 2005, placing all eleven ships under the same formation; the anti-submarine suite was also gradually removed as the RSN refocused its ASW capability on other platforms.[143][144] The eleven patrol vessels formed the combined 182/189 Squadron until May 2016 when the first Independence-class littoral mission vessel completed its sea trials; 189 Squadron was subsequently subsumed into 182 Squadron.[145][146]

On 11 December 2020, the final two patrol vessels RSS Gallant and RSS Freedom were decommissioned.[147] Four vessels of the class were converted into Sentinel-class maritime security and response vessels.

Bases

[edit]Tuas Naval Base

[edit]

Tuas Naval Base (TNB) is located at the western tip of Singapore and occupies 0.28 km2 (0.11 mi2) of land. It was officially opened on 2 September 1994 by Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong. For about two decades, Brani Naval Base was the RSN's only base. An expansion of the fleet in the early 1980s meant that more space was needed for the fleet and its shore infrastructure. However, this was not possible as the land around Brani was reserved for use by the port authority to develop container facilities.[148] As a result, Tuas was selected as the site for a new naval base.

Better utilisation of space at TNB resulted in two and a half times more berthing space than Brani, even though TNB only has a shoreline of 850 m (0.5 mi). Provision was also made for recreational facilities. Automation was incorporated into the design of TNB to reduce manpower requirements, such as mechanical ramps for the loading and unloading of vehicles and an automatic storage and retrieval system. It also has a floating dock which can lift 600 tonnes and transfer a ship from sea to land to facilitate repairs and maintenance.[149]

The base has since been enclosed to the west by land reclamation in Tuas South. The missile corvettes, patrol vessels, littoral mission vessels and mine counter-measures vessels are based at TNB.

RSS Singapura Changi Naval Base

[edit]

Changi Naval Base (CNB) is the latest naval facility of the RSN and was built to replace Brani Naval Base. Located on 1.28 km2 (0.50 mi2) of reclaimed land at the eastern tip of Singapore, it was officially opened on 21 May 2004 by Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong. Its 6.2 km (3.9 mi) berthing space can accommodate an aircraft carrier and is often used by visiting ships of the USN.[150]

Automation was incorporated into the design of CNB to reduce manpower requirements. It has an automated underground ammunition depot that allows ammunition to be loaded onto the ships and an automated warehouse system to store items. The base has a fibre optic broadband network for information management. The base was also designed to be environment-friendly, with small-scale wind turbines powering the lights along the breakwaters at night. Conventional roof construction materials were substituted by thin film solar panels and the solar energy generated lights the base. In addition, seawater is used in the air-conditioning system.[151]

The submarines, frigates and landing ships tank are based at CNB. Co-located in CNB is the Naval Military Experts Institute, also known as RSS Panglima— named in honour of the first ship of the navy.[152][153]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The official RSN anniversary books[12][13] and website[18] states that only Bedok and Panglima formed the initial navy, omitting the Singapura for unknown reasons despite it being one of three ships transferred to Singapore.[19]

- ^ The RSN claims the date as the day of their official establishment and commemorates Navy Day on 5 May every year.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b International Institute for Strategic Studies (15 February 2023). The Military Balance 2023. London: Routledge. pp. 286–287. ISBN 9781032508955.

- ^ "Commercially operated ship arrives to support training of RSN NSmen". The Straits Times. 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Leadership Biographies". Ministry of Defence (Singapore). 10 March 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Foizee, Bahauddin (13 September 2019). "Why Singapore's Navy Should Be Taken Seriously". The National Interest. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Rupert Herbert-Burns; Caitlyn Antrim; Halae Fuller; Lindsay Dolan (16 July 2012). Indian Ocean Rising: Maritime Security and Policy Challenges. Henry L. Stimson Center. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-9836674-6-9.

- ^ Brimelow, Ben. "How a tiny city-state became a military powerhouse with the best air force and navy in Southeast Asia". Business Insider. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Drop in piracy in regional waters". The Straits Times. 20 September 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Piracy attempt foiled by S'pore, Indonesian navies". The Straits Times. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Fokker 50 Maritime Patrol Aircraft". Republic of Singapore Navy - Careers. Archived from the original on 5 September 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Moktar, Faris (22 August 2017). "Busy shipping lane's narrow passageway hard for vessels to navigate". Today. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Foizee, Bahauddin (19 August 2019). "Singapore's ambitious naval procurement plans". Asia Times. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g A Maritime Force for a Maritime Nation: Celebrating 50 Years of the Navy. Straits Times Press. 2017. ISBN 9789811130304.

- ^ a b Onwards and Upwards: Celebrating 40 Years of the Navy. SNP International Publishing. 2007. ISBN 978-981-248-147-4.

- ^ Lee Kuan Yew: Hard Truths to Keep Singapore Going. Straits Times Press. February 2011. ISBN 9789814266727.

- ^ "Our Mission". Official website of the Republic of Singapore Navy. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Singapore: A Country Study. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1987. p. 184. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "History". Royal Malaysian Navy (Former Communications Branch Members). Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "History and Heritage". Republic of Singapore Navy. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Lim, Adrian (10 February 2017). "Changi Naval Base to get new name: RSS Singapura - Changi Naval Base". The Straits Times. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Panglima's history". The New Paper. 3 April 1992.

Jan 1, 1966: Recommissioned RSS Panglima when Singapore separated from Malaysia.

- ^ Tim, Huxley (2001). Defending the Lion City. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-118-2.

- ^ Quek, Sherlyn. "Flashback: 5 RSN firsts". Pioneer. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b Lim, Kenneth (1 May 2017). "Warships from 20 countries to dock at Singapore's first international maritime review". Channel News Asia. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017.

- ^ "History". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 21 February 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2004.

- ^ "Expanding armada keeps sea-lanes open". Singapore Monitor. 1 July 1985. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Onwards and Upwards: Celebrating 40 Years of the Navy. SNP International Pub. 2007. ISBN 9789812481474.

- ^ Villanueva, Adrian (22 February 2017). "RSS Singapura name in line with naval tradition". The Straits Times. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "About our Navy - History". Republic of Singapore Navy - Careers. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Omar, Marsita. "British withdrawal from Singapore". Singapore Infopedia. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Colonel James Aeria, Commander of Republic of Singapore Navy, at a press conference on the 3,710 South Vietnamese refugees on board 25 ships now anchored off Singapore". National Archives of Singapore. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "Malaysia to keep naval base in Spore". The Straits Times. 19 August 1970. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "First navy chief of Singapore dies". The Straits Times. 26 April 1994. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d "PFM Sea Wolf". Global Security. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ a b Tan, Jun Han. "RSN50: Making waves". Pioneer. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Tracing our Origins". Republic of Singapore Navy. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Teo, Jing Ting. "The first frogmen". Pioneer. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Address by the Minister of Defence, Mr Howe Yoon Chong, at the Commissioning Ceremony of the Coastal Patrol Craft at Pulau Brani Naval Base" (PDF) (Press release). Singapore Government. 27 October 1981. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Onwards and Upwards: Celebrating 40 Years of the Navy. SNP International Publishing. 2007. p. 31. ISBN 978-981-248-147-4.

- ^ Withington, Tom. "Singapore's Blue Water Aspirations". Asian Military Review (May 2009): 4–8. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Haftel, Yoram (21 May 2012). Regional Economic Institutions and Conflict Mitigation: Design, Implementation, and the Promise of Peace. University of Michigan Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0472118342.

- ^ "Findings of the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA)'S Inquiry into the Collision between ANL Indonesia and RSS Courageous". Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Collision at Sea Findings: Statement by DPM and Minister for Defence, Dr Tony Tan" (PDF). National Archives of Singapore. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Operation Blue Heron, East Timor, 1999 - 2003". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Operation Flying Eagle is Activated after Asian Tsunami". National Library Board. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Reconstruction of Iraq". Republic of Singapore Navy - Careers. Archived from the original on 5 September 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Ong, Hong Tat (15 May 2016). "Marine Speedster". Pioneer.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (1 July 2019). "SAF using NSFs in more roles ahead of manpower crunch". The Straits Times. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "The Malacca Straits Patrol". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Singapore Navy Joins Counterpiracy CTF 151". United States Navy. 23 April 2009. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Chow, Jermyn (17 March 2014). "Singapore sends 151 servicemen to join anti-piracy patrols in Gulf of Aden". The Straits Times. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "CTF 151: Counter-piracy". Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) A 33-nation naval partnership. 17 September 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ a b Wong, Kelvin (17 May 2019). "IMDEX 2019: Singapore navy confirms 16 m-class USVs aboard future unmanned vehicle 'mothership'". Janes. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Lee, Hui Chieh. "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane: Singapore sends more help to search for flight MH370". The Straits Times. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "AirAsia plane crash: Eerie images from underwater show fuselage found in Java Sea". News Corp Australia Network. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Singapore Navy sends 3 vessels to help in QZ8501 search". Channel News Asia. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Xue, Jian Yue (30 June 2014). "SAF mulls buying larger ship to better aid in disaster relief". Today. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Lai, Linette (11 February 2019). "Singapore repeats call for Malaysia to withdraw vessels in Republic's waters off Tuas after collision". The Straits Times. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Kaur, Karamjit (7 December 2018). "New Johor Baru port limits go beyond Kuala Lumpur's past claims: Khaw Boon Wan". The Straits Times. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Kaur, Karamjit (8 April 2019). "Singapore, Malaysia suspend implementation of overlapping port limits". The Straits Times. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Restructuring the RSN's Capabilities to Strengthen Singapore's Maritime Security Capabilities". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Singapore navy launches second and third Invincible-class submarines". Channel News Asia. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (20 February 2019). "Invincible, first of Singapore's biggest and most advanced submarines, launches in Germany". The Straits Times. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Yeo, Mike (28 March 2023). "Singapore buys six combat vessels that can serve as drone motherships". Defense News. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Mahmud, Aqil Haziq (6 July 2018). "Meet the Navy's new 'mothership' that fights with unmanned drones and vessels". Channel News Asia. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Ho, Tim (30 January 2020). "Whither Singapore's Joint Multi Mission Ship?". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (2 March 2020). "Parliament: SAF to restructure to deal with cyber, terrorism, maritime threats". The Straits Times. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ @Ng_Eng_Hen (2 March 2020). "The Maritime Security Task Force will acquire new purpose-built platforms to better deal with maritime threats like sea robberies and intrusions into Singapore Territorial Waters. #SGBudget2020" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Organisation". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Our Formations". Republic of Singapore Navy. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "New Chief of Navy at the Helm". Ministry of Defence. 10 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (21 December 2018). "Ng Eng Hen commends Maritime Security Task Force". The Straits Times. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Tan, Tam Mei (21 January 2017). "From NSFs to the nation's elite divers". The Straits Times. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Factsheet - Naval Logistics Command (NALCOM)" (PDF). National Archives of Singapore. Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Sin, Harry (2016). "Ready, Set, Fire!" (PDF). Navy News (1/2016): 24. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "79th MIDA/16th MDEC 1 - Midshipman Sea Training Deployment 2/17". Ministry of Defence - Officer Cadet School. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Seven Years of Legacy". MINDEF Singapore. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Navy Officers' Advanced School (NAS)". MINDEF. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ "Moments in Basic Specialisation Course 1". MINDEF. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Formations". www.mindef.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 29 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "STET POLARIS – The RSN's Own Training Ship". Navy News (4/2010): 4. 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Wong, Benjamin (2016). "The Making of a RSN Sailor" (PDF). Navy News (1/2016): 22. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Smooth sailing onboard STET Polaris". Electronic Review: 7. August 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Auto, Hermes (17 February 2019). "A rare look at RSN submarine training: Crew can now take out adversary within minutes | The Straits Times". www.straitstimes.com.

- ^ "Singapore Navy launches new submarine training centre". AsiaOne. 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Diving into the deep with Singapore's 'hidden defenders'". Today Online. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Zhang, Lim Min (18 February 2019). "Chief trainer has been through gruelling 'Perisher' submarine command course". The New Paper.

- ^ "PIONEER - Invincible beneath the waves". www.mindef.gov.sg. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "NAVY LAUNCHES ITS SECOND AND THIRD INVINCIBLE-CLASS SUBMARINES". MINDEF Singapore. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Naval Careers - Naval Diving Unit". Naval Careers. Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Singapore's naval divers special: What it takes to pass". The Straits Times. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Formidable Frigate". DCNS. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- ^ Minnick, Wendell (14 May 2007). "Singapore's Navy Cruises Toward Blue-Water Force". Defence News. Army Times Publishing Company.

- ^ "Target acquisition – MAST highlights missile-defense concepts". Defence Technology International. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Chow, Jeremy (16 January 2009). "Stealth ships set for action". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ Waldron, Greg (20 January 2013). "Singapore orders two additional S-70B helicopters". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Republic of Singapore Navy Turns 40 and Commissions its First Frigate RSS Formidable". Defence Science and Technology Agency. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Commissioning Ceremony of RSS Stalwart and RSS Supreme". Defence Science and Technology Agency. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "MINDEF Signs Contract with ST Engineering for the Construction of Eight New Vessels". Ministry of Defence. 30 January 2013. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ "ST Engineering Wins Newbuild Contract for Eight Naval Vessels for the Republic of Singapore Navy". ST Engineering. 30 January 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ "Operationalisation of the Littoral Mission Vessel (LMV) Programme". Ministry of Defence. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Speech by Senior Minister of State for Defence Dr Mohamad Maliki Bin Osman, at the Launching Ceremony of the Fourth Littoral Mission Vessel" (PDF). Defence Science and Technology Agency. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Chia, Chong Jin (31 January 2020). "Littoral Mission Vessel fleet complete & mission-ready". Pioneer. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Archus, Dorian (24 July 2019). "Singapore and Indonesian Navies Conduct Bilateral Exercise Eagle Indopura". Naval Post. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (14 November 2017). "RSN gears up amid regional challenges, with two new littoral mission vessels turning operational". The Straits Times. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Singapore Navy Commissions Final Three Littoral Mission Vessels". Ministry of Defence. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Characteristics of the Endurance class LST". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 26 September 2004.

- ^ "Speech by Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam, Deputy Prime Minister & Minister for Defence, on the Occasion of the Commissioning Ceremony for the RSN Landing Ship Tank, RSS Endurance & RSS Resolution Held on Saturday, 18 March 2000 at 10:00 am at Tuas Naval Base". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ^ "Safe in my wake". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2005.

- ^ "The Next Wave". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ "Units". Official website of the Republic of Singapore Navy. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Challenger". Kockums. Archived from the original on 5 February 2005. Retrieved 4 February 2005.

- ^ "Submarine Tropicalisation Programme". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2005.

- ^ Kaplan, George. "The Republic of Singapore Navy". Navy League of Australia. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Republic of Singapore Navy Launches New Submarine Training Centre". mindef.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Kockums receives Singapore order to two submarines". Kockums. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2005.

- ^ "Singapore Navy Launches its First Archer-Class Submarine". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ "RSS Archer submarine now operational, will join 171 Squadron". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Choong, William (17 June 2009). "New subs not sign of regional arms race". The Straits Times. pp. A21.

- ^ "ThyssenKrupp wins submarine order from Singapore". Reuters. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Loke, Kok Fai. "Singapore Navy to add 2 more submarines to fleet". Channel News Asia. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Tamir Eshel (5 December 2013). "Singapore's Type-218SG – Forerunner of a new Submarine Class?". Defence Update. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Foizee, Bahauddin (9 August 2019). "Singapore's Naval Ambition". Via News Agency. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Progress of Key SAF Projects". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Singapore navy launches second and third Invincible-class submarines". CNA. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Fish, Tim. "Underwater Arms Race". Asian Military Review. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Singapore Hosts Regional Submarine Conference". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "Victory Class Corvettes". Lürssen. Archived from the original on 23 November 2005.

- ^ N, Suresh (7 June 2000). "1988 – RSN's Missile Corvettes". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 26 September 2004.

- ^ Soong, Martin (2 September 1986). "Republic orders six anti-submarine missile gunboats". Business Times. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Chung, Kam Sam; Wibawa, Martin Sulaiman. "Making a difference through innovation: Missile Corvettes upgrade story" (PDF). Defence Science and Technology Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Singapore Revamps Its Victory-Class Corvettes". Naval Today. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Saunders, Stephen (2007). Jane's Fighting Ships, 2007-2008. Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-2799-5.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (2 March 2020). "Parliament: SAF to restructure to deal with cyber, terrorism, maritime threats". The Straits Times. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: New Maritime Security and Response Flotilla to Enhance Maritime Security". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Infographic: Maritime Security and Response Flotilla". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Day at Sea on Board Protector". Pioneer. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (26 January 2021). "2 refurbished RSN patrol vessels back in action as part of new flotilla". The Straits Times. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Fast Patrol Boats TNC 45". Lürssen. Archived from the original on 23 November 2005.

- ^ "Launched - first Singapore built missile gunboat". The Straits Times. 16 November 1972. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "1975 – Missile Gunboats". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 26 September 2004.

- ^ "Missile Gunboats Retire After 33 Years of Distinguished Service". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ "One dead in naval collision". BBC News. 4 January 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2003.

- ^ Till, Geoffrey; Supriyanto, Atriandi (2018). Naval Modernisation in Southeast Asia. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-319-58406-5. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Lin, Yuankai. "COSCOM Muscles Up For Challenges Ahead" (PDF). Navy News. 2005 (2): 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Lin, Yuankai. "COSCOM Expands" (PDF). Navy News. 2005 (1): 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2005.

- ^ "LMV Independence joins the RSN family". Ministry of Defence. 27 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Lim, Min Zhang (11 December 2020). "Pioneer RSN sailor shares memories as last two patrol vessels are decommissioned". The Straits Times. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ N, Suresh (7 September 2000). "Tuas Naval Base". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2005.

- ^ Foo-Tan, Germaine (7 September 2003). "Tuas Naval Base". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2005.

- ^ "Our Bases". Republic of Singapore Navy. Archived from the original on 8 February 2005. Retrieved 4 March 2005.

- ^ "DSTA gives Changi Naval Base a 'green' edge". Defence Science and Technology Agency. Archived from the original on 28 May 2006. Retrieved 7 May 2005.

- ^ "1956 – Serving with pride: The RSS Panglima". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "2004 – Changi Naval Base". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the RSN

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch