Swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is a symbol used in various Eurasian religions and cultures, and it is also seen in some African and American ones. In the Western world, it is more widely recognized as a symbol of the German Nazi Party who appropriated it for their party insignia starting in the early 20th century. The appropriation continues with its use by neo-Nazis around the world.[1][2][3][4] The swastika was and continues to be used as a symbol of divinity and spirituality in Indian religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.[1][5][6][7][8] It generally takes the form of a cross,[A] the arms of which are of equal length and perpendicular to the adjacent arms, each bent midway at a right angle.[10][11]

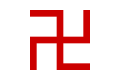

The word swastika comes from Sanskrit: स्वस्तिक, romanized: svastika, meaning 'conducive to well-being'.[1][12] In Hinduism, the right-facing symbol (clockwise) (卐) is called swastika, symbolizing surya ('sun'), prosperity and good luck, while the left-facing symbol (counter-clockwise) (卍) is called sauvastika, symbolising night or tantric aspects of Kali.[1] In Jain symbolism, it is the part of Jain flag.[13] It represents Suparshvanatha – the seventh of 24 Tirthankaras (spiritual teachers and saviours), while in Buddhist symbolism it represents the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.[1][14][15] In the different Indo-European traditions, the swastika symbolises fire, lightning bolts, and the sun.[16] The symbol is found in the archaeological remains of the Indus Valley civilisation[17] and Samarra, as well as in early Byzantine and Christian artwork.[18][19]

Although used for the first time as a symbol of international antisemitism by far-right Romanian politician A. C. Cuza prior to World War I,[20][21][22] it was a symbol of auspiciousness and good luck for most of the Western world until the 1930s,[2] when the German Nazi Party adopted the swastika as an emblem of the Aryan race. As a result of World War II and the Holocaust, in the West it continues to be strongly associated with Nazism, antisemitism,[23][24] white supremacism,[25][26] or simply evil.[27][28] As a consequence, its use in some countries, including Germany, is prohibited by law.[B] However, the swastika remains a symbol of good luck and prosperity in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain countries such as Nepal, India, Thailand, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, China and Japan, and carries various other meanings for peoples around the world, such as the Akan, Hopi, Navajo, and Tlingit peoples. It is also commonly used in Hindu marriage ceremonies and Dipavali celebrations.

Etymology and nomenclature

With well-being (swasti) we would follow along our path, like the Sun and the Moon. May we meet up with one who gives in return, who does not smite (harm), with one who knows.

The word swastika is derived from the Sanskrit root swasti, which is composed of su 'good, well' and asti 'is; it is; there is'.[31] The word swasti occurs frequently in the Vedas as well as in classical literature, meaning 'health, luck, success, prosperity', and it was commonly used as a greeting.[32][33] The final ka is a common suffix that could have multiple meanings.[34]

According to Monier-Williams, a majority of scholars consider the swastika to originally be a solar symbol.[32] The sign implies well-being, something fortunate, lucky, or auspicious.[32][35] It is alternatively spelled in contemporary texts as svastika,[36] and other spellings were occasionally used in the 19th and early 20th century, such as suastika.[37] It was derived from the Sanskrit term (Devanagari स्वस्तिक), which transliterates to svastika under the commonly used IAST transliteration system, but is pronounced closer to swastika when letters are used with their English values.

The earliest known use of the word swastika is in Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī, which uses it to explain one of the Sanskrit grammar rules, in the context of a type of identifying mark on a cow's ear.[31] Most scholarship suggests that Pāṇini lived in or before the 4th century BCE,[38][39] possibly in 6th or 5th century BCE.[40][41]

An important early use of the word swastika in a European text was in 1871 with the publications of Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered more than 1,800 ancient samples of swastika symbols and variants thereof while digging the Hisarlik mound near the Aegean Sea coast for the history of Troy. Schliemann linked his findings to the Sanskrit swastika.[42][43][44]

By the 19th century, the term swastika was adopted into the English lexicon,[45] replacing the previous gammadion from Greek γαμμάδιον. In 1878, Irish scholar Charles Graves used swastika as the common English name for the symbol, after defining it as equivalent to the French term croix gammée – a cross with arms shaped like the Greek letter gamma (Γ).[46] Shortly thereafter, British antiquarians Edward Thomas and Robert Sewell separately published their studies about the symbol, using swastika as the common English term.[47][48]

The concept of a "reversed" swastika was probably first made among European scholars by Eugène Burnouf in 1852 and taken up by Schliemann in Ilios (1880), based on a letter from Max Müller that quotes Burnouf. The term sauwastika is used in the sense of 'backward swastika' by Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1894): "In India it [the gammadion] bears the name of swastika, when its arms are bent towards the right, and sauwastika when they are turned in the other direction."[49]

Other names for the symbol include:

- tetragammadion (Greek: τετραγαμμάδιον) or cross gammadion (Latin: crux gammata; French: croix gammée), as each arm resembles the Greek letter Γ (gamma)[10]

- hooked cross (German: Hakenkreuz), angled cross (Winkelkreuz), or crooked cross (Krummkreuz)

- cross cramponned, cramponnée, or cramponny in heraldry, as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron (German: Winkelmaßkreuz)

- fylfot, chiefly in heraldry and architecture

- tetraskelion (Greek: τετρασκέλιον), literally meaning 'four-legged', especially when composed of four conjoined legs (compare triskelion/triskele [Greek: τρισκέλιον])[50]

- ugunskrusts (Latvian for 'fire cross, cross of fire"; other names – pērkonkrusts ('cross of thunder', 'thunder cross'), cross of Perun or of Perkūnas), cross of branches, cross of Laima)

- whirling logs (Navajo): can denote abundance, prosperity, healing, and luck[51]

In various European languages, it is known as the fylfot, gammadion, tetraskelion, or cross cramponnée (a term in Anglo-Norman heraldry); German: Hakenkreuz; French: croix gammée; Italian: croce uncinata; Latvian: ugunskrusts. In Mongolian it is called хас (khas) and mainly used in seals. In Chinese it is called 卍字 (wànzì), pronounced manji in Japanese, manja (만자) in Korean and vạn tự or chữ vạn in Vietnamese. In Balti/Tibetan language it is called yung drung.[citation needed]

Appearance

All swastikas are bent crosses based on a chiral symmetry, but they appear with different geometric details: as compact crosses with short legs, as crosses with large arms and as motifs in a pattern of unbroken lines. Chirality describes an absence of reflective symmetry, with the existence of two versions that are mirror images of each other. The mirror-image forms are typically described as left-facing or left-hand (卍) and right-facing or right-hand (卐).

The compact swastika can be seen as a chiral irregular icosagon (20-sided polygon) with fourfold (90°) rotational symmetry. Such a swastika proportioned on a 5 × 5 square grid and with the broken portions of its legs shortened by one unit can tile the plane by translation alone. The main Nazi flag swastika used a 5 × 5 diagonal grid, but with the legs unshortened.[54]

Written characters

The swastika was adopted as a standard character in Chinese, "卍" (pinyin: wàn) and as such entered various other East Asian languages, including Chinese script. In Japanese the symbol is called "卍" (Hepburn: manji) or "卍字" (manji).

The swastika is included in the Unicode character sets of two languages. In the Chinese block it is U+534D 卍 (left-facing) and U+5350 for the swastika 卐 (right-facing);[55] The latter has a mapping in the original Big5 character set,[56] but the former does not (although it is in Big5+[57]). In Unicode 5.2, two swastika symbols and two swastikas were added to the Tibetan block: swastika U+0FD5 ࿕ RIGHT-FACING SVASTI SIGN, U+0FD7 ࿗ RIGHT-FACING SVASTI SIGN WITH DOTS, and swastikas U+0FD6 ࿖ LEFT-FACING SVASTI SIGN, U+0FD8 ࿘ LEFT-FACING SVASTI SIGN WITH DOTS.[58]

Origin

European uses of swastikas are often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the sun cross of Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "proto-writing" symbol systems, such as the Vinča script,[59] which appeared during the Neolithic.[60]

North pole

According to René Guénon, the swastika represents the north pole, and the rotational movement around a centre or immutable axis (axis mundi), and only secondly it represents the Sun as a reflected function of the north pole. As such it is a symbol of life, of the vivifying role of the supreme principle of the universe, the absolute God, in relation to the cosmic order. It represents the activity (the Hellenic Logos, the Hindu Om, the Chinese Taiyi, 'Great One') of the principle of the universe in the formation of the world.[61] According to Guénon, the swastika in its polar value has the same meaning of the yin and yang symbol of the Chinese tradition, and of other traditional symbols of the working of the universe, including the letters Γ (gamma) and G, symbolising the Great Architect of the Universe of Masonic thought.[62]

According to the scholar Reza Assasi, the swastika represents the north ecliptic north pole centred in ζ Draconis, with the constellation Draco as one of its beams. He argues that this symbol was later attested as the four-horse chariot of Mithra in ancient Iranian culture. They believed the cosmos was pulled by four heavenly horses who revolved around a fixed centre in a clockwise direction. He suggests that this notion later flourished in Roman Mithraism, as the symbol appears in Mithraic iconography and astronomical representations.[63]

According to the Russian archaeologist Gennady Zdanovich, who studied some of the oldest examples of the symbol in Sintashta culture, the swastika symbolises the universe, representing the spinning constellations of the celestial north pole centred in α Ursae Minoris, specifically the Little and Big Dipper (or Chariots), or Ursa Minor and Ursa Major.[64] Likewise, according to René Guénon-the swastika is drawn by visualising the Big Dipper/Great Bear in the four phases of revolution around the pole star.[65]

Comet

In their 1985 book Comet, Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan argue that the appearance of a rotating comet with a four-pronged tail as early as 2,000 years BCE could explain why the swastika is found in the cultures of both the Old World and the pre-Columbian Americas. The Han dynasty Book of Silk (2nd century BCE) depicts such a comet with a swastika-like symbol.[66]

Bob Kobres, in a 1992 paper, contends that the swastika-like comet on the Han-dynasty manuscript was labelled a "long tailed pheasant star" (dixing) because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or footprint.[67] Similar comparisons had been made by J. F. Hewitt in 1907,[68] as well as a 1908 article in Good Housekeeping.[69] Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside of China.[67]

Four winds

In Native American culture, particularly among the Pima people of Arizona, the swastika is a symbol of the four winds. Anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing noted that among the Pima the symbol of the four winds is made from a cross with the four curved arms (similar to a broken sun cross) and concludes "the right-angle swastika is primarily a representation of the circle of the four wind gods standing at the head of their trails, or directions."[70]

Historical uses

Prehistory

The earliest known swastikas are from 10,000 BCE – part of "an intricate meander pattern of joined-up swastikas" found on a late paleolithic figurine of a bird, carved from mammoth ivory, found in Mezine, Ukraine.[71] However, the age of 10,000 BCE is a conservative estimate, and the true age may be as old as 17,000 BCE.[72] It has been suggested that this swastika may be a stylised picture of a stork in flight.[73] As the carving was found near phallic objects, this may also support the idea that the pattern was a fertility symbol.[2]

In the mountains of Iran, there are swastikas or spinning wheels inscribed on stone walls, which are estimated to be more than 7,000 years old. One instance is in Khorashad, Birjand, on the holy wall Lakh Mazar.[74][75]

Mirror-image swastikas (clockwise and counter-clockwise) have been found on ceramic pottery in the Devetashka cave, Bulgaria, dated to 6,000 BCE.[76]

In Asia, swastika symbols first appear in the archaeological record around[77] 3000 BCE in the Indus Valley Civilisation.[78][79] It also appears in the Bronze and Iron Age cultures around the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In all these cultures, swastika symbols do not appear to occupy any marked position or significance, appearing as just one form of a series of similar symbols of varying complexity. In the Zoroastrian religion of Persia, the swastika was a symbol of the revolving sun, infinity, or continuing creation.[80][81] It is one of the most common symbols on Mesopotamian coins.[1] Some researchers put forth the hypothesis that the swastika moved westward from the Indian subcontinent to Finland, Scandinavia, the Scottish Highlands and other parts of Europe.[82][better source needed] In England, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on Ilkley Moor, such as the Swastika Stone.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[83] in Iron Age designs of the northern Caucasus (Koban culture), and in Neolithic China in the Majiayao culture.[84]

Swastikas are also seen in Egypt during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, and is dated between 300 and 600 CE.[85]

The Tierwirbel (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals"[86]) is a characteristic motif in Bronze Age Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and later also in Iron Age Scythian and European (Baltic[87] and Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an animal motif, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed to the Pacific and even North America (especially Moundville).[88]

- The Samarra bowl, from Iraq, circa 4,000 BCE, held at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction.[89]

- Swastika seals from Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan, of the Indus Valley civilisation, circa 2,100 – 1,750 BCE, preserved at the British Museum[90]

- Sauwastika monogram at the end of Karna Chaupar Cave edict of Ashoka

Caucasus

In Armenia the swastika is called the "arevakhach" and "kerkhach" (Armenian: կեռխաչ)[91][dubious – discuss] and is the ancient symbol of eternity and eternal light (i.e. God). Swastikas in Armenia were found on petroglyphs from the copper age, predating the Bronze Age. During the Bronze Age it was depicted on cauldrons, belts, medallions and other items.[92]

Swastikas can also be seen on early Medieval churches and fortresses, including the principal tower in Armenia's historical capital city of Ani.[91] The same symbol can be found on Armenian carpets, cross-stones (khachkar) and in medieval manuscripts, as well as on modern monuments as a symbol of eternity.[93]

Old petroglyphs of four-beam and other swastikas were recorded in Dagestan, in particular, among the Avars.[94] According to Vakhushti of Kartli, the tribal banner of the Avar khans depicted a wolf with a standard with a double-spiral swastika.[95]

Petroglyphs with swastikas were depicted on medieval Vainakh tower architecture (see sketches by scholar Bruno Plaetschke from the 1920s).[96] Thus, a rectangular swastika was made in engraved form on the entrance of a residential tower in the settlement Khimoy, Chechnya.[96]

- The petroglyph with swastikas, Gegham mountains, Armenia, circa 8,000 – 5,000 BCE[97]

- Avar folk swastika

- Swastika on the medieval tower arche in Khimoy, Chechnya

Europe

Iron Age attestations of swastikas can be associated with Indo-European cultures such as the Illyrians,[98] Indo-Iranians, Celts, Greeks, Germanic peoples and Slavs. In Sintashta culture's "Country of Towns", ancient Indo-European settlements in southern Russia, it has been found a great concentration of some of the oldest swastika patterns.[64]

Swastika shapes have been found on numerous artefacts from Iron Age Europe.[91][99][100][98][10]

The swastika shape (also called a fylfot) appears on various Germanic Migration Period and Viking Age artifacts, such as the 3rd-century Værløse Fibula from Zealand, Denmark, the Gothic spearhead from Brest-Litovsk, today in Belarus, the 9th-century Snoldelev Stone from Ramsø, Denmark, and numerous Migration Period bracteates drawn left-facing or right-facing.[101]

The pagan Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo, England, contained numerous items bearing swastikas, now housed in the collection of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.[102][failed verification] A swastika is clearly marked on a hilt and sword belt found at Bifrons in Kent, in a grave of about the 6th century.

Hilda Ellis Davidson theorised[clarification needed] that the swastika symbol was associated with Thor, possibly representing his Mjolnir – symbolic of thunder – and possibly being connected to the Bronze Age sun cross.[102] Davidson cites "many examples" of swastika symbols from Anglo-Saxon graves of the pagan period, with particular prominence on cremation urns from the cemeteries of East Anglia.[102] Some of the swastikas on the items, on display at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, are depicted with such care and art that, according to Davidson, it must have possessed special significance as a funerary symbol.[102] The runic inscription on the 8th-century Sæbø sword has been taken as evidence of the swastika as a symbol of Thor in Norse paganism.

The bronze frontispiece of a ritual pre-Christian (c. 350–50 BCE) shield found in the River Thames near Battersea Bridge (hence "Battersea Shield") is embossed with 27 swastikas in bronze and red enamel.[103] An Ogham stone found in Aglish, County Kerry, Ireland (CIIC 141) was modified into an early Christian gravestone, and was decorated with a cross pattée and two swastikas.[104] The Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) contains swastika-shaped ornamentation. At the Northern edge of Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire, there is a swastika-shaped pattern engraved in a stone known as the Swastika Stone.[105] A number of swastikas have been found embossed in Galician metal pieces and carved in stones, mostly from the Castro culture period, although there also are contemporary examples (imitating old patterns for decorative purposes).[106][107]

The ancient Baltic thunder cross symbol (pērkona krusts (cross of Perkons); also fire cross, ugunskrusts) is a swastika symbol used to decorate objects, traditional clothing and in archaeological excavations.[108][109]

According to painter Stanisław Jakubowski, the "little sun" (Polish: słoneczko) is an Early Slavic pagan symbol of the Sun; he claimed it was engraved on wooden monuments built near the final resting places of fallen Slavs to represent eternal life. The symbol was first seen in his collection of Early Slavic symbols and architectural features, which he named Prasłowiańskie motywy architektoniczne (Polish: Early Slavic Architectural Motifs). His work was published in 1923.[110]

The Boreyko coat of arms with a red swastika was used by several noble families in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[111]

According to Boris Kuftin, the Russians often used swastikas as a decorative element and as the basis of the ornament on traditional weaving products.[112] Many can be seen on a women's folk costume from the Meshchera Lowlands.[112]

According to some authors, Russian names popularly associated with the swastika include veterok ("breeze"),[113] ognevtsi ("little flames"), "geese", "hares" (a towel with a swastika was called a towel with "hares"), or "little horses".[114] The similar word "koleso" ("wheel") was used for rosette-shaped amulets, such as a hexafoil-thunder wheel ![]() ) in folklore, particularly in the Russian North.[115][116]

) in folklore, particularly in the Russian North.[115][116]

An object very much like a hammer or a double axe is depicted among the magical symbols on the drums of Sami noaidi, used in their religious ceremonies before Christianity was established. The name of the Sami thunder god was Horagalles, thought to derive from "Old Man Thor" (Þórr karl). Sometimes on the drums, a male figure with a hammer-like object in either hand is shown, and sometimes it is more like a cross with crooked ends, or a swastika.[102]

- Ancient symbol the Hands of God or "Hands of Svarog" (Polish: Ręce Swaroga)[117]

- Swastika on the Lielvārde Belt, Latvia

Southern and eastern Asia

The icon has been of spiritual significance to Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[8][1] The swastika is a sacred symbol in the Bön religion, native to Tibet.

Hinduism

The swastika is an important Hindu symbol.[1][8] The swastika symbol is commonly used before entrances or on doorways of homes or temples, to mark the starting page of financial statements[citation needed], and mandalas constructed for rituals such as weddings or welcoming a newborn.[1][118]

The swastika has a particular association with Diwali, being drawn in rangoli (coloured sand) or formed with deepak lights on the floor outside Hindu houses and on wall hangings and other decorations.[119]

In the diverse traditions within Hinduism, both the clockwise and counterclockwise swastika are found, with different meanings. The clockwise or right hand icon is called swastika, while the counterclockwise or left hand icon is called sauwastika or sauvastika.[1] The clockwise swastika is a solar symbol (Surya), suggesting the motion of the Sun in India (the northern hemisphere), where it appears to enter from the east, then ascend to the south at midday, exiting to the west.[1] The counterclockwise sauwastika is less used; it connotes the night, and in tantric traditions it is an icon for the goddess Kali, the terrifying form of Devi Durga.[1] The symbol also represents activity, karma, motion, wheel, and in some contexts the lotus.[5][6] According to Norman McClelland its symbolism for motion and the Sun may be from shared prehistoric cultural roots.[120]

- A swastika is typical in Hindu temples

- A Hindu temple in Rajasthan, India

- A swastika inside a temple

- The Balinese Hindu pura Goa Lawah entrance

- A Balinese Hindu shrine

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the swastika is considered to symbolise the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.[1][14] The left-facing sauwastika is often imprinted on the chest, feet or palms of Buddha images. It is an aniconic symbol for the Buddha in many parts of Asia and homologous with the dharma wheel.[6] The shape symbolises eternal cycling, a theme found in the samsara doctrine of Buddhism.[6]

The swastika symbol is common in esoteric tantric traditions of Buddhism, along with Hinduism, where it is found with chakra theories and other meditative aids.[118] The clockwise symbol is more common, and contrasts with the counterclockwise version common in the Tibetan Bon tradition and locally called yungdrung.[121]

In East Asia, the swastika is prevalent in Buddhist monasteries and communities. It is commonly found in Buddhist temples, religious artifacts, texts related to Buddhism and schools founded by Buddhist religious groups. It also appears as a design or motif (singularly or woven into a pattern) on textiles, architecture and various decorative objects as a symbol of luck and good fortune. The icon is also found as a sacred symbol in the Bon tradition, but in the left-facing orientation.[52][122]

Jainism

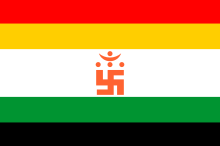

In Jainism, it is a symbol of the seventh tīrthaṅkara, Suparśvanātha.[1] In the Śvētāmbara tradition, it is also one of the aṣṭamaṅgala or eight auspicious symbols. All Jain temples and holy books must contain the swastika and ceremonies typically begin and end with creating a swastika mark several times with rice around the altar. Jains use rice to make a swastika in front of statues and then put an offering on it, usually a ripe or dried fruit, a sweet (Hindi: मिठाई miṭhāī), or a coin or currency note. The four arms of the swastika symbolise the four places where a soul could be reborn in samsara, the cycle of birth and death – svarga "heaven", naraka "hell", manushya "humanity" or tiryancha "as flora or fauna" – before the soul attains moksha "salvation" as a siddha, having ended the cycle of birth and death and become omniscient.[7]

Prevalence in southern Asia

In Bhutan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, the swastika is common. Temples, businesses and other organisations, such as the Buddhist libraries, Ahmedabad Stock Exchange and the Nepal Chamber of Commerce,[124] use the swastika in reliefs or logos.[122] Swastikas are ubiquitous in Indian and Nepalese communities, located on shops, buildings, transport vehicles, and clothing. The swastika remains prominent in Hindu ceremonies such as weddings. The left facing sauwastika symbol is found in tantric rituals.[1]

Musaeus College in Colombo, Sri Lanka, a Buddhist girls' school, has a left facing swastika in their school logo.

In India, Swastik and Swastika, with their spelling variants, are first names for males and females respectively, for instance with Swastika Mukherjee. The Emblem of Bihar contains two swastikas.

In Bhutan, swastika motifs are found in architecture, fabrics and religious ceremonies.

Among the predominantly Hindu population of Bali, in Indonesia, swastikas are common in temples, homes and public spaces. Similarly, the swastika is a common icon associated with Buddha's footprints in Theravada Buddhist communities of Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia.[122]

The Tantra-based new religious movement Ananda Marga (Devanagari: आनन्द मार्ग, meaning 'Path of Bliss') uses a motif similar to the Raëlians, but in their case the apparent star of David is defined as intersecting triangles with no specific reference to Jewish culture.

- One of common carving patterns of Torajan people in Indonesia.

- The symbol of the Ananda Marga movement

Spread to eastern Asia

The swastika is an auspicious symbol in China where it was introduced from India with Buddhism.[125] In 693, during the Tang dynasty, it was declared as "the source of all good fortune" and was called wan by Wu Zetian becoming a Chinese word.[125] The Chinese character for wan (pinyin: wàn) is similar to a swastika in shape and has two different variations:《卐》and 《卍》. As the Chinese character wan (卐 or 卍) is homonym for the Chinese word of "ten thousand" (万) and "infinity", as such the Chinese character is itself a symbol of immortality[126] and infinity.[127]: 175 It was also a representation of longevity.[127]: 175

The Chinese character wan could be used as a stand-alone《卐》or《卍》or as be used as pairs《卐 卍》in Chinese visual arts, decorative arts, and clothing due to its auspicious connotation.[127]: 175

Adding the character wan (卐 or 卍) to other auspicious Chinese symbols or patterns can multiply that wish by 10,000 times.[125][127]: 175 It can be combined with other Chinese characters, such as the Chinese character shou《壽》for longevity where it is sometimes even integrated into the Chinese character shou to augment the meaning of longevity.[127]: 175

The paired swastika symbols (卐 and 卍) are included, at least since the Liao Dynasty (907–1125 CE), as part of the Chinese writing system and are variant characters for 《萬》 or 《万》 (wàn in Mandarin, 《만》(man) in Korean, Cantonese, and Japanese, vạn in Vietnamese) meaning "myriad".[128]

The character wan can also be stylized in the form of the xiangyun, Chinese auspicious clouds.

When the Chinese writing system was introduced to Japan in the 8th century, the swastika was adopted into the Japanese language and culture. It is commonly referred as the manji (lit. "10,000-character"). Since the Middle Ages, it has been used as a mon by various Japanese families such as Tsugaru clan, Hachisuka clan or around 60 clans that belong to Tokugawa clan.[129] The city of Hirosaki in Aomori Prefecture designates this symbol as its official flag, which stemmed from its use in the emblem of the Tsugaru clan, the lords of Hirosaki Domain during the Edo period.[citation needed]

In Japan, the swastika is also used as a map symbol and is designated by the Survey Act and related Japanese governmental rules to denote a Buddhist temple.[130] Japan has considered changing this due to occasional controversy and misunderstanding by foreigners.[131] The symbol is sometimes censored in international versions of Japanese works, such as anime.[132] Censorship of this symbol in Japan and in Japanese media abroad has been subject to occasional controversy related to freedom of speech, with critics of the censorship arguing it does not respect history nor freedom of speech.[131][132]

In Chinese and Japanese art, swastikas are often found as part of a repeating pattern. One common pattern, called sayagata in Japanese, comprises left- and right-facing swastikas joined by lines.[133] As the negative space between the lines has a distinctive shape, the sayagata pattern is sometimes called the key fret motif in English.[citation needed]

Many Chinese religions make use of swastika symbols, including Guiyidao and Shanrendao. The Red Swastika Society, formed in China in 1922 as the philanthropic branch of Guiyidao, became the largest supplier of emergency relief in China during World War II, in the same manner as the Red Cross in the rest of the world. The Red Swastika Society abandoned mainland China in 1954, settling first in Hong Kong then in Taiwan. They continue to use the red swastika as their symbol.[134]

The Falun Gong qigong movement, founded in China in the early 1990s, uses a symbol that features a large swastika surrounded by four smaller (and rounded) ones, interspersed with yin-and-yang symbols.[135]

- Chinese character wan integrated into one of the stylistic versions of the Chinese character shou

- Paired character wan on a dragon robe, Qing dynasty

- Swastika on a temple in Korea

- Symbol of Shanrendao, a Confucian-Taoism religious movement in Northeast China

- Flag of the Red Swastika Society, the largest emergency relief group in China during World War II

- The pattern of the Goddess of Thunder (wa:on) of Saisiyat people in Taiwan.

- The symbol of the Falun Gong movement

Classical Europe

Ancient Greek architectural, clothing and coin designs are replete with single or interlinking swastika motifs. There are also gold plate fibulae from the 8th century BCE decorated with an engraved swastika.[136] Related symbols in classical Western architecture include the cross, the three-legged triskele or triskelion and the rounded lauburu. The swastika symbol is also known in these contexts by a number of names, especially gammadion,[137] or rather the tetra-gammadion. The name gammadion comes from its being seen as being made up of four Greek gamma (Γ) letters. Ancient Greek architectural designs are replete with the interlinking symbol.

In Greco-Roman art and architecture, and in Romanesque and Gothic art in the West, isolated swastikas are relatively rare, and the swastika is more commonly found as a repeated element in a border or tessellation. Swastikas often represented perpetual motion, reflecting the design of a rotating windmill or watermill. A meander of connected swastikas makes up the large band that surrounds the Augustan Ara Pacis.

A design of interlocking swastikas is one of several tessellations on the floor of the cathedral of Amiens, France.[138] A border of linked swastikas was a common Roman architectural motif,[139] and can be seen in more recent buildings as a neoclassical element. A swastika border is one form of meander, and the individual swastikas in such a border are sometimes called Greek keys. There have also been swastikas found on the floors of Pompeii.[140]

Swastikas were widespread among the Illyrians, symbolising the Sun and the fire. The Sun cult was the main Illyrian cult; a swastika in clockwise motion is interpreted in particular as a representation of the movement of the Sun.[98][141][142]

The swastika has been preserved by the Albanians since Illyrian times as a pagan symbol commonly found in a variety of contexts of Albanian folk art, including traditional tattooing, grave art, jewellery, clothes, and house carvings. The swastika (Albanian: kryqi grepç or kryqi i thyer, "hooked cross") and other crosses in Albanian tradition represent the Sun (Dielli) and the fire (zjarri, evidently called with the theonym Enji). In Albanian paganism fire is regarded as the offspring of the Sun and fire calendar rituals are practiced in order to give strength to the Sun and to ward off evil.[143][144]

Medieval and early modern Europe

Middle Ages

In Christianity, the swastika is used as a hooked version of the Christian Cross, the symbol of Christ's victory over death. Some Christian churches built in the Romanesque and Gothic eras are decorated with swastikas, carrying over earlier Roman designs. Swastikas are prominently displayed in a mosaic in the St. Sophia church of Kyiv, Ukraine dating from the 12th century. They also appear as a repeating ornamental motif on a tomb in the Basilica of St. Ambrose in Milan.[145]

A ceiling painted in 1910 in the church of St Laurent in Grenoble has many swastikas. It can be visited today because the church became the archaeological museum of the city. A proposed direct link between it and a swastika floor mosaic in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Amiens, which was built on top of a pagan site at Amiens, France in the 13th century, is considered unlikely. The stole worn by a priest in the 1445 painting of the Seven Sacraments by Rogier van der Weyden presents the swastika form simply as one way of depicting the cross.

Swastikas also appear in art and architecture during the Renaissance and Baroque era. The fresco The School of Athens shows an ornament made out of swastikas, and the symbol can also be found on the facade of the Santa Maria della Salute, a Roman Catholic church and minor basilica located at Punta della Dogana in the Dorsoduro sestiere of the city of Venice.

In the Polish First Republic swastika symbols were also popular with the nobility. Several noble houses, e.g. Boreyko, Borzym, and Radziechowski from Ruthenia, also had swastikas as their coat of arms. The family reached its greatness in the 14th and 15th centuries and its crest can be seen in many heraldry books produced at that time.

The swastika was also a heraldic symbol, for example on the Boreyko coat of arms, used by noblemen in Poland and Ukraine. In the 19th century a swastika was one of the Russian Empire's symbols and was used on coinage as a backdrop to the Russian eagle.[146]

- Bashkirs symbol of the sun and fertility

- Mosaic swastika in an excavated Byzantine church in Shavei Tzion, (Israel)

- A swastika composed of Hebrew letters as a mystical symbol from the Jewish Kabbalistic work "Parashat Eliezer", from the 18th century or earlier

- Swastikas on the vestments of the effigy of Bishop William Edington (d. 1366) in Winchester Cathedral

- The Victorian-era reproduction of the Swastika Stone on Ilkley Moor, which sits near the original to aid visitors in interpreting the carving

Rediscovery by Heinrich Schliemann

At Troy near the Dardanelles, Heinrich Schliemann's 1871–1875 archaeological excavations discovered objects decorated with swastikas.[147]: 101–105 [148][149]: 31 [150]: 31 Hearing of this, the director of the French School at Athens, Émile-Louis Burnouf, wrote to Schliemann in 1872, stating "the Swastika should be regarded as a sign of the Aryan race". Burnouf told Schliemann that "It should also be noted that the Jews have completely rejected it".[151]: 89 Accordingly, Schliemann believed the Trojans to have been Aryans: "The primitive Trojans, therefore, belonged to the Aryan race, which is further sufficiently proved by the symbols on the round terra-cottas".[147]: 157 [151]: 90 Schliemann accepted Burnouf's interpretation.[151]: 89

This winter, I have read in Athens many excellent works of celebrated scholars on Indian antiquities, especially Adalbert Kuhn, Die Herakunft des Feuers; Max Müller's Essays; Émile Burnouf, La Science des Religions and Essai sur le Vêda; as well as several works by Eugène Burnouf; and I now perceive that these crosses upon the Trojan terra-cottas are of the highest importance to archæology.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, 1875[147]: 101

Schliemann believed that use of swastikas spread widely across Eurasia.[152]

… I am now able to prove that … the 卍, which I find in Émile Burnouf's Sanscrit lexicon, under the name of "suastika," and with the meaning εὖ ἐστι, or as the sign of good wishes, were already regarded, thousands of years before Christ, as religious symbols of the very greatest importance among the early progenitors of the Aryan races in Bactria and in the villages of the Oxus, at a time when Germans, Indians, Pelasgians, Celts, Persians, Slavonians and Iranians still formed one nation and spoke one language.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, 1875[147]: 101–102

Schliemann established a link between the swastika and Germany. He connected objects he excavated at Troy to objects bearing swastikas found in Germany near Königswalde on the Oder.[148][149]: 31 [150]: 31 [151]: 90

For I recognise at the first glance the "suastika" upon one of those three pot bottoms, which were discovered on Bishop's Island near Königswalde on the right bank of the Oder, and have given rise to very many learned discussions, while no one recognised the mark as that exceedingly significant religious symbol of our remote ancestors.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, 1875[147]: 102

Sarah Boxer, in an article in 2000 in The New York Times, described this as a "fateful link".[148] According to Steven Heller, "Schliemann presumed that the swastika was a religious symbol of his German ancestors which linked ancient Teutons, Homeric Greeks and Vedic India".[149]: 31 According to Bernard Mees, "Of all of the pre-runic symbols, the swastika has always been the most popular among scholars" and "The origin of swastika studies must be traced to the excitement generated by the archaeological finds of Heinrich Schliemann at Troy".[153]

After his excavations at Troy, Schliemann began digging at Mycenae. According to Cathy Gere, "Having burdened the swastika symbol with such cultural, religious and racial significance in Troy and Its Remains, it was incumbent on Schliemann to find the symbol repeated at Mycenae, but its occurrence turned out to be disappointingly infrequent".[151]: 91 Gere writes that "He did his best with what he had":[151]: 91

The cross with the marks of four nails may often be seen; as well as the 卍, which is usually also represented with four points indicating the four nails, thus ࿘. These signs cannot but represent the suastika, formed by two pieces of wood, which were laid across and fixed with four nails, and in the joint of which the holy fire was produced by friction by a third piece of wood. But both the cross and the 卍 occur for the most part only on the vases with geometrical patterns.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Mycenæ, 1878[154]: 66–68

Gere points out that although Schliemann wrote that the motif "may often be seen", his 1878 book Mycenæ did not have illustrations of any examples.[151]: 91 Schliemann described "a small and thick terra-cotta disk" on which "are engraved a number of 卍's, the sign which occurs so frequently in the ruins of Troy", but as Gere notes, he did not publish an illustration.[154]: 77 [151]: 91

Among the gold grave goods at Grave Circles A and B was a repoussé roundel in grave III of Grave Circle A, the ornamentation of which Schliemann thought was "derived" from the swastika:

The curious ornamentation in the centre, which so often recurs here, seems to me to be derived from the ࿘, the more so as the points which are thought to be the marks of the nails, are seldom missing; the artist has only added two more arms and curved all of them.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Mycenæ, 1878[154]: 165–166

According to Gere, this motif is "completely dissimilar" to the swastika, and that Schliemann was "straining desperately after the same connection".[151]: 91 Nevertheless, the Mycenaean Greeks and the Trojan people both came to be identified as representatives of the Aryan race: "Despite the difficulties with linking the symbolism of Troy and Mycenae, the common Aryan roots of the two peoples became something of a truism".[151]: 91

The house Schliemann had had built in Panepistimiou Street in Athens by 1880, Iliou Melathron, is decorated with swastika symbols and motifs in numerous places, including the ironwork railing and gates, the window bars, the ceiling fresco of the entrance hall, and the entire floor of one room.[151]: 117–123

Following Schliemann, academic studies on the swastika were published by Ludvig Müller, Michał Żmigrodzki, Eugène Goblet d'Alviella, Thomas Wilson, Oscar Montelius and Joseph Déchelette.[153]

German occultism and pan-German nationalism

On 24 June 1875, Guido von List commemorated the 1500th anniversary of the German victory over the Roman Empire at the Battle of Carnuntum by burying a swastika of eight wine bottles beneath the Heidentor (lit. 'Heathens' Gate') in the ruins of Carnuntum.[155]: 35 In 1891, List began to claim that heraldry's division of the field was derived from the shapes of runes.[155]: 71 He claimed that the medieval German Vehmgericht was a survival of the pre-Christian Armanist priest-kings and that the cryptic letters "SSGG" inscribed on vehmic knives represented a double sig rune followed by two swastikas.[155]: 76

In 1897, Max Ferdinand Sebaldt von Werth published Wanidis and Sexualreligion, which according to Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke in The Occult Roots of Nazism, "described the sexual-religion of the Aryans, a sacred practice of eugenics designed to maintain the purity of the race".[155]: 51 Both works were "illustrated with the magical curved-armed armed swastika".[155]: 51 Influenced by Sebaldt, List published in Der Scherer – erstes illustriertes Tiroler Witzblatt an article ("Germanischer Lichtdienst") which claimed the swastika was a sacred symbol of the Aryans representing the "fire-whisk" (Feuerquirl) with which the creator deity Mundelföri had begun the world.[155]: 52 In September 1903, List published an article discussing the creation of the universe, the "old-Aryan sexual religion", reincarnation, karma, "Wotanism", and "Armanism" from his theosophical viewpoint, which was illustrated by triskelions and various swastikas in the Viennese occult journal Die Gnosis.[155]: 41, 52 According to Goodrick-Clarke, "This article marked the first stage in List's articulation of a Germanic occult religion, the principal concern of which was racial purity".[155]: 52

Between 1905 and 1907, List published articles in the Leipziger Illustrierte Zeitung arguing that the swastika, the triskelion, and the sun-wheel were all "Armanist" occult symbols (Armanen runes) concealed in German heraldry, and in 1908 his Das Geheimnis der Runen (lit. 'The Secret of the Runes') argued that the swastika or Armanen rune "Gibor" was represented in blazons including different heraldic crosses and kinked versions of the ordinaries pale, bend, and fess.[155]: 72 List argued that the swastika, triskelion, and other Armanen runes had been concealed in 15th-century rose windows and curvilinear tracery in late Gothic architecture.[155]: 74

List's 1908 book Die Rita der Ario-Germanen (lit. 'The Rite of the Ario-Germans') had chapter headings with triskelions, swastikas, and other symbols attached. The work laid out his belief in an ancient priestly Armanenschaft of Wotanist initiates and identified the "Ario-Germans" as a "race" identical with Helena Blavatsky's theosophical fifth "root race".[155]: 52–53 List's 1910 Die Religion der Ario-Germanen (lit. 'The Religion of the Ario-Germans') discussed Yuga cycles and the Kali Yuga, proposing a mathematical relationship with the Grímnismál of the Edda.[155]: 53 His Die Bilderschrift der Ario-Germanen (lit. 'The Picture-Writing of the Ario-Germans') of the same year connected Blavatsky's Hindu-inspired cosmic cycles (kalpas) with the realms of Muspelheim (Muspilheim), Asgard, Vanaheimr (Wanenheim), and Midgard, each with a corresponding symbol. Blavatsky's first Astral and second Hyperborean races List connected with the descendants of Ymir and Orgelmir, her third Lemurian race was his race of Thrudgelmir, her fourth Atlantean race his descendants of Bergelmir, and Blavatsky's fifth root race List identified as the "Ario-Germans".[155]: 53–54 According to Goodrick-Clarke, List again argued that the clockwise swastika was a holy symbol of the "Ario-Germans":

A series of anti-clockwise triskelions and swastikas and inverted triangles symbolized stages of cosmic evolution in the downsweep of the cycle (i.e. the evolution from unity to multiplicity), while their clockwise and upright counterparts connoted the return path to the godhead. The skewed super-imposition of the of these 'falling' and 'rising' sigils created complex sigils like the hexagram and the Maltese Cross. List asserted that these latter symbols were utterly sacred, because they embraced the two antithetical forces of all creation: as the representative symbols of the zenith of multiplicity at the outermost limit of the cycle, they denoted the Ario-German god-man, the highest form of life ever to evolve in the universe.[155]: 54

List's 1914 Die Ursprache der Ario-Germanen (lit. 'The Proto-Language of the Ario-Germans') adopted the geological ideas of theosophist William Scott-Elliot and claimed that fragments of Atlantis remained part of Europe, pointing to rocking stones in Lower Austria and European megaliths as evidence. From Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, List took on occult ideas about the Aryan homeland Arktogäa (a lost polar continent), and struggle the Ario-German master races and the non-Aryan slave races, and the Knights Templar.[155]: 54–55 List believed that the Templars had been adepts of "Armanism" during the Middle Ages' Christian ascendancy, and that they had been suppressed for worshipping the Maltese cross that List believed to derived from a superimposed clockwise and anti-clockwise swastika and which he identified with Baphomet.[155]: 61–62 Members of the inner circle of the Guido von List Society, the Hoher Armanen-Orden (HAO), expressed their membership of the occult priesthood with swastikas. Heinrich Winter, Friedrich Oskar Wannieck, and Georg Hauerstein senior's first wife all had their graves decorated with swastikas.[155]: 65

Lanz, a former Cistercian, established the Order of the New Templars or ONT (Ordo Novi Templi lit. 'New Order of the Temple') in imitation of the Knights Templar whose monastic rule had been written by the Cistercian Bernard of Clairvaux and whom Lanz believed had aimed to establish "a Greater Germanic order-state, which would encompass the entire Mediterranean area and extend its sphere of influence deep into the Middle East" whose eventual suppression had been a triumph of racial inferiority over the "Ario-Christian" eugenics practised by the Templars.[155]: 108 As the headquarters of his revived Templar Order and as a museum of Aryan anthropology, Lanz bought Burg Werfenstein on the Danube, where on Christmas Day 1907, he hoisted his heraldic banner (gules, an eagle's wing argent) and the flag of the ONT: a swastika gules surrounded by four fleurs-de-lis azure on a field or.[155]: 106, 109, 113

Post-Schliemann popularity

The swastika (gammadion, fylfot) symbol became a popular symbol in the Western world in the early 20th century, and was often used for ornamentation.

The Benedictine choir school at Lambach Abbey, Upper Austria, which Hitler attended for several months as a boy, had a swastika chiseled into the monastery portal and also the wall above the spring grotto in the courtyard by 1868. Their origin was the personal coat of arms of Theoderich Hagn, abbot of the monastery in Lambach, which bore a golden swastika with slanted points on a blue field.[156]

The British author and poet Rudyard Kipling used the symbol on the cover art of a number of his works, including The Five Nations, 1903, which has it twinned with an elephant. Once Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power, Kipling ordered that swastikas should no longer adorn his books.[citation needed] In 1927, a red swastika defaced by a Union Jack was proposed as a flag for the Union of South Africa.[157]

The logo of H/f. Eimskipafjelag Íslands[158] was a swastika, called "Thor's hammer", from its founding in 1914 until the Second World War when it was discontinued and changed to read only the letters Eimskip.

The swastika was also used by the women's paramilitary organisation Lotta Svärd, which was banned in 1944 in accordance with the Moscow Armistice between Finland and the allied Soviet Union and Britain.

Also, the insignias of the Cross of Liberty, designed by Gallen-Kallela in 1918, have swastikas. The 3rd class Cross of Liberty is depicted in the upper left corner of the standard of the President of Finland, who is the grand master of the order, too.[159]

Latvia adopted the swastika, for its Air Force in 1918/1919 and continued its use until the Soviet occupation in 1940.[160][161] The cross itself was maroon on a white background, mirroring the colours of the Latvian flag. Earlier versions pointed counter-clockwise, while later versions pointed clock-wise and eliminated the white background.[162][163] Various other Latvian Army units and the Latvian War College[164] (the predecessor of the National Defence Academy) also had adopted the symbol in their battle flags and insignia during the Latvian War of Independence.[165] A stylised fire cross is the base of the Order of Lāčplēsis, the highest military decoration of Latvia for participants of the War of Independence.[166] The Pērkonkrusts, an ultra-nationalist political organisation active in the 1930s, also used the fire cross as one of its symbols.

The swastika symbol (Lithuanian: sūkurėlis) is a traditional Baltic ornament,[108][167] found on relics dating from at least the 13th century.[168] The sūkurėlis for Lithuanians represents the history and memory of their Lithuanian ancestors as well as the Baltic people at large.[168] There are monuments in Lithuania such as the Freedom Monument in Rokiškis where swastikas can be found.[168]

Starting in 1917, Mikal Sylten's staunchly antisemitic periodical, Nationalt Tidsskrift took up the swastika as a symbol, three years before Adolf Hitler chose to do so.[169]

The left-handed swastika was a favourite sign of the last Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. She wore a talisman in the form of a swastika, put it everywhere for happiness, including on her suicide letters from Tobolsk,[170] later drew with a pencil on the wall and in the window opening of the room in the Ipatiev House, which served as the place of the last imprisonment of the royal family and on the wallpaper above the bed.[171]

The Russian Provisional Government of 1917 printed a number of new bank notes with right-facing, diagonally rotated swastikas in their centres.[172] The banknote design was initially intended for the Mongolian national bank but was re-purposed for Russian rubles after the February revolution. Swastikas were depicted and on some Soviet credit cards (sovznaks) printed with clichés that were in circulation in 1918–1922.[173]

During the Russian Civil War, swastikas were present in the symbolism of the uniform of some units of the White Army Asiatic Cavalry Division of Baron Ungern in Siberia and Bogd Khanate of Mongolia, which is explained by the significant number of Buddhists within it.[174] The Red Army's ethnic Kalmyk units wore distinct armbands featuring a swastika with "РСФСР" (Roman: "RSFSR") inscriptions on them.[175]

New religious movements

Besides its use as a religious symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, which can be traced back to pre-modern traditions, the swastika was also incorporated into a large number of new religious movements which were established in the West in the modern period.

In the 1880s, the U.S.-origined Theosophical Society adopted a swastika as part of its seal, along with an Om, a hexagram or star of David, an Ankh, and an Ouroboros. Unlike the much more recent Raëlian movement, the Theosophical Society symbol has been free from controversy, and the seal is still used. The current seal also includes the text "There is no religion higher than truth."[176]

The Raëlian Movement, whose adherents believe extraterrestrials created all life on earth, use a symbol that is often the source of considerable controversy: an interlaced star of David and a swastika. The Raëlians say the Star of David represents infinity in space whereas the swastika represents infinity in time – no beginning and no end in time, and everything being cyclic.[177] In 1991, the symbol was changed to remove the swastika, out of respect to the victims of the Holocaust, but as of 2007 it has been restored to its original form.[178]

The swastika is a holy symbol in neopagan Germanic Heathenry, along with the hammer of Thor and runes. This tradition – which is found in Scandinavia, Germany, and elsewhere – considers the swastika to be derived from a Norse symbol for the sun. Their use of the symbol has led people to accuse them of being a neo-Nazi group.[179][180][181]

- The seal of the Theosophical society

- The Raëlian symbol with the swastika

- The alternative Raëlian with the spiral

World War II

Use in Nazism

The swastika was widely used in Europe at the start of the 20th century. It symbolised many things to the Europeans, with the most common symbolism being of good luck and auspiciousness.[23] Before the Nazis, the swastika was already in use as a symbol of German völkisch nationalist movements (Völkische Bewegung).

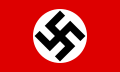

In the wake of widespread popular usage, in post-World War I Germany, the newly established Nazi Party formally adopted the swastika in 1920.[23][182] The Nazi Party emblem was a black swastika rotated 45 degrees on a white circle on a red background. This insignia was used on the party's flag, badge, and armband. Hitler also designed his personal standard using a black swastika sitting flat on one arm, not rotated.[183]

In his 1925 work Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler writes: "I myself, meanwhile, after innumerable attempts, had laid down a final form; a flag with a red background, a white disk, and a black hooked cross in the middle. After long trials I also found a definite proportion between the size of the flag and the size of the white disk, as well as the shape and thickness of the hooked cross."

When Hitler created a flag for the Nazi Party, he sought to incorporate both the swastika and "those revered colours expressive of our homage to the glorious past and which once brought so much honour to the German nation". (Red, white, and black were the colours of the flag of the old German Empire.) He also stated: "As National Socialists, we see our program in our flag. In red, we see the social idea of the movement; in white, the nationalistic idea; in the hooked cross, the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man, and, by the same token, the victory of the idea of creative work."[184]

The swastika was also understood as "the symbol of the creating, effecting life" (das Symbol des schaffenden, wirkenden Lebens) and as "race emblem of Germanism" (Rasseabzeichen des Germanentums).[185]

The concepts of racial hygiene and scientific racism were central to Nazism.[186][187] High-ranking Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg noted that the Indo-Aryan peoples were both a model to be imitated and a warning of the dangers of the spiritual and racial "confusion" that, he believed, arose from the proximity of races. The Nazis co-opted the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan master race.

On 14 March 1933, shortly after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany, the NSDAP flag was hoisted alongside Germany's national colours. As part of the Nuremberg Laws, the NSDAP flag – with the swastika slightly offset from centre – was adopted as the sole national flag of Germany on 15 September 1935.[188]

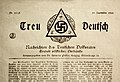

- Heinrich Pudor's völkisch Treu Deutsch ('True German') 1918 with a swastika. From the collections of Leipzig City Museum.

- German World War I helmet with swastika used by a member of the Marinebrigade Ehrhardt, a right-wing paramilitary free corps, participating in the Kapp Putsch 1920

- Cross of Honour of the German Mother (1939–1945) given to German mothers of four or more children

Use by the Allies

During World War II it was common to use small swastikas to mark air-to-air victories on the sides of Allied aircraft, and at least one British fighter pilot inscribed a swastika in his logbook for each German plane he shot down.[189]

Americas

The swastika has been used in the art and iconography of multiple indigenous peoples of North America, including the Hopi, Navajo, and Tlingit.[191] Swastikas were founds on pottery from the Mississippi valley and on copper objects in the Hopewell Mounds in Ross County, Ohio, and on objects associated with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (S.E.C.C.).[192][193] To the Hopi it represents the wandering Hopi clan.[citation needed] The Navajo symbol, called tsin náálwołí ("whirling log"), represents humanity and life, and is used in healing rituals.[194][195] A brightly coloured First Nations saddle featuring swastika designs is on display at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada.[196]

Before the 1930s, the symbol for the 45th Infantry Division of the United States Army was a red diamond with a yellow swastika, a tribute to the large Native American population in the southwestern United States. It was later replaced with a thunderbird symbol.

In the 20th century, traders encouraged Native American artists to use the symbol in their crafts, and it was used by the US Army 45th Infantry Division, an all-Native American division.[197][198][199] The symbol lost popularity in the 1930s due to its associations with Nazi Germany. In 1940, partially due to government encouragement, community leaders from several different Native American tribes made a statement promising to no longer use the symbol.[200][194][201][199] However, the symbol has continued to be used by Native American groups, both in reference to the original symbol and as a memorial to the 45th Division, despite external objections to its use.[4][199][201][202][203][204] The symbol was used on state road signs in Arizona from the 1920s until the 1940s.[205]

The town of Swastika, Ontario, Canada, and the hamlet of Swastika, New York were named after the symbol.

From 1909 to 1916, the K-R-I-T automobile, manufactured in Detroit, Michigan, used a right-facing swastika as their trademark.

The flag of the Guna people (also "Kuna Yala" or "Guna Yala") of Panama. This flag, adopted in 1925, has a swastika symbol that they call Naa Ukuryaa. According to one explanation, this ancestral symbol symbolises the octopus that created the world, its tentacles pointing to the four cardinal points.[206] In 1942, a ring was added to the centre of the flag to differentiate it from the symbol of the Nazi Party (this version subsequently fell into disuse).[207]

- The swastika in North America

- Chief William Neptune of the Passamaquoddy, wearing a headdress and outfit adorned with swastikas

- Chilocco Indian Agricultural School basketball team in 1909

- Fernie Swastikas hockey team in 1922

- Original insignia of the 45th Infantry Division

- Pillow cover offered by the Girls' Club in The Ladies Home Journal in 1912

- Arizona state highway marker (1927)

Africa

Swastikas can be seen in various African cultures. In Ethiopia a swastika is carved in the window of the famous 12th-century Biete Maryam, one of the Rock-Hewn Churches, Lalibela.[3] In Ghana, the adinkra symbol nkontim, used by the Akan people to represent loyalty, takes the form of a swastika. Nkontim symbols could be found on Ashanti gold weights and clothing.[208]

- Carved fretwork forming a swastika on the Biete Maryam in Ethiopia

- Nkontim adinkra symbol from Ghana, representing loyalty and readiness to serve

- Ashanti weight in Africa

Modern adoptions

A ugunskrusts ('fire cross') is used by the Baltic neopaganism movements Dievturība in Latvia and Romuva in Lithuania.[209]

In the early 1990s, the former dissident and one of the founders of Russian neo-paganism Alexey Dobrovolsky first gave the name "kolovrat" (Russian: коловрат, literally 'spinning wheel') to a four-beam swastika, identical to the Nazi symbol, and later transferred this name to an eight-beam rectangular swastika.[210] According to the historian and religious scholar Roman Shizhensky, Dobrovolsky took the idea of the swastika from the work "The Chronicle of Oera Linda"[211] by the Nazi ideologist Herman Wirth, the first head of the Ahnenerbe.[212] Dobrovolsky introduced the eight-beam "kolovrat" as a symbol of "resurgent paganism."[213] He considered this version of the Kolovrat a pagan sign of the sun and, in 1996, declared it a symbol of the uncompromising "national liberation struggle" against the "Zhyd yoke".[214] According to Dobrovolsky, the meaning of the "kolovrat" completely coincides with the meaning of the Nazi swastika.[215] The kolovrat is the most commonly used religious symbol within neopagan Slavic Native Faith (a.k.a. Rodnovery).[216][217]

In 2005, authorities in Tajikistan called for the widespread adoption of the swastika as a national symbol. President Emomali Rahmonov declared the swastika an Aryan symbol, and 2006 "the year of Aryan culture", which would be a time to "study and popularise Aryan contributions to the history of the world civilisation, raise a new generation (of Tajiks) with the spirit of national self-determination, and develop deeper ties with other ethnicities and cultures".[218]

- The Baltic fire-cross

- Polish: Słoneczko ("little sun"); kolovrat ("spinning wheel")

- A kolovrat flag, introduced by Alexey Dobrovolsky

Modern controversy

Post- World War II stigmatisation

Because of its use by Nazi Germany, the swastika since the 1930s has been largely associated with Nazism. In the aftermath of World War II, it has been considered a symbol of hate in the West,[219] and of white supremacy in many Western countries.[220]

As a result, all use of it, or its use as a Nazi or hate symbol, is prohibited in some countries, including Germany. In some countries, such as the United States (in the 2003 case Virginia v. Black), the highest courts have ruled that the local governments can prohibit the use of swastika along with other symbols such as cross burning, if the intent of the use is to intimidate others.[24]

Germany

The German and Austrian postwar criminal code makes the public showing of the swastika, the sig rune, the Celtic cross (specifically the variations used by white power activists), the wolfsangel, the odal rune and the Totenkopf skull illegal, except for certain enumerated exemptions. It is also censored from the reprints of 1930s railway timetables published by the Reichsbahn. The swastikas on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples are exempt, as religious symbols cannot be banned in Germany.[221]

A controversy was stirred by the decision of several police departments to begin inquiries against anti-fascists.[222] In late 2005 police raided the offices of the punk rock label and mail order store "Nix Gut Records" and confiscated merchandise depicting crossed-out swastikas and fists smashing swastikas. In 2006 the Stade police department started an inquiry against anti-fascist youths using a placard depicting a person dumping a swastika into a trashcan. The placard was displayed in opposition to the campaign of right-wing nationalist parties for local elections.[223]

On Friday, 17 March 2006, a member of the Bundestag, Claudia Roth reported herself to the German police for displaying a crossed-out swastika in multiple demonstrations against neo-Nazis, and subsequently got the Bundestag to suspend her immunity from prosecution. She intended to show the absurdity of charging anti-fascists with using fascist symbols: "We don't need prosecution of non-violent young people engaging against right-wing extremism." On 15 March 2007, the Federal Court of Justice of Germany (Bundesgerichtshof) held that the crossed-out symbols were "clearly directed against a revival of national-socialist endeavours", thereby settling the dispute for the future.[224][225][226]

On 9 August 2018, Germany lifted the ban on the usage of swastikas and other Nazi symbols in video games. "Through the change in the interpretation of the law, games that critically look at current affairs can for the first time be given a USK age rating," USK managing director Elisabeth Secker told CTV. "This has long been the case for films and with regards to the freedom of the arts, this is now rightly also the case with computer and videogames."[227][228]

Legislation in other European countries

- Until 2013 in Hungary, it was a criminal misdemeanour to publicly display "totalitarian symbols", including the swastika, the SS insignia, and the Arrow Cross, punishable by custodial arrest.[229][230] Display for academic, educational, artistic or journalistic reasons was allowed at the time. The communist symbols of hammer and sickle and the red star were also regarded as totalitarian symbols and had the same restriction by Hungarian criminal law until 2013.[229]

- In Latvia, public display of Nazi and Soviet symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is prohibited in public events since 2013.[231][232] However, in a court case from 2007 a regional court in Riga held that the swastika can be used as an ethnographic symbol, in which case the ban does not apply.[233]

- In Lithuania, public display of Nazi and Soviet symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is an administrative offence, punishable by a fine from 150 to 300 euros. According to judicial practice, display of a non-Nazi swastika is legal.[234]

- In Poland, public display of Nazi symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is a criminal offence punishable by up to eight years of imprisonment. The use of the swastika as a religious symbol is legal.[235]

- In Geneva, Switzerland, a new constitution article banning the use of hate symbols, emblems, and other hateful images was passed in June 2024, which included banning the use of the swastika.[236]

The European Union's Executive Commission proposed a European Union-wide anti-racism law in 2001, but European Union states failed to agree on the balance between prohibiting racism and freedom of expression.[237] An attempt to ban the swastika across the EU in early 2005 failed after objections from the British Government and others. In early 2007, while Germany held the European Union presidency, Berlin proposed that the European Union should follow German Criminal Law and criminalise the denial of the Holocaust and the display of Nazi symbols including the swastika, which is based on the Ban on the Symbols of Unconstitutional Organisations Act. This led to an opposition campaign by Hindu groups across Europe against a ban on the swastika. They pointed out that the swastika has been around for 5,000 years as a symbol of peace.[238][239] The proposal to ban the swastika was dropped by Berlin from the proposed European Union wide anti-racism laws on 29 January 2007.[237]

Outside Europe

The manufacture, distribution or broadcasting of a swastika, with the intent to propagate Nazism, is a crime in Brazil as dictated by article 20, paragraph 1, of federal statute 7.716, passed in 1989. The penalty is a two to five years prison term and a fine.[240]

The public display of Nazi-era German flags (or any other flags) is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech.[241] The Nazi Reichskriegsflagge has also been seen on display at white supremacist events within United States borders, side by side with the Confederate battle flag.[242]

In 2010, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) downgraded the swastika from its status as a Jewish hate symbol, saying "We know that the swastika has, for some, lost its meaning as the primary symbol of Nazism and instead become a more generalised symbol of hate."[243] The ADL notes on their website that the symbol is often used as "shock graffiti" by juveniles, rather than by individuals who hold white supremacist beliefs, but it is still a predominant symbol among American white supremacists (particularly as a tattoo design) and used with antisemitic intention.[244]

In 2022, Victoria was the first Australian state to ban the display of the Nazi's swastika. People who intentionally break this law will face a one-year jail sentence, a fine of 120 penalty units ($23,077.20 AUD as of 2023, equivalent to £12,076.66 or US$15,385.57), or both.[245][246]

Media

In 2010, Microsoft officially spoke out against use of the swastika by players of the first-person shooter Call of Duty: Black Ops. In Black Ops, players are allowed to customise their name tags to represent whatever they want. The swastika can be created and used, but Stephen Toulouse, director of Xbox Live policy and enforcement, said players with the symbol on their name tag will be banned (if someone reports it as inappropriate) from Xbox Live.[247]

In the Indiana Jones Stunt Spectacular in Disney Hollywood Studios in Orlando, Florida, the swastikas on German trucks, aircraft and actor uniforms in the reenactment of a scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark were removed in 2004. The swastikas have been replaced by a stylised Greek cross.[248]

Use by neo-Nazis

As with many neo-Nazi groups across the world, the American Nazi Party used the swastika as part of its flag before its first dissolution in 1967. The symbol was chosen by the organisation's founder, George Lincoln Rockwell.[249] It was "re-used" by successor organisations in 1983, without the publicity Rockwell's organisation enjoyed.[citation needed]

The swastika, in various iconographic forms, is one of the hate symbols identified in use as graffiti in US schools, and is described as such in a 1999 US Department of Education document, "Responding to Hate at School: A Guide for Teachers, Counsellors and Administrators", edited by Jim Carnes, which provides advice to educators on how to support students targeted by such hate symbols and address hate graffiti. Examples given show that it is often used alongside other white supremacist symbols, such as those of the Ku Klux Klan, and note a "three-bladed" variation used by skinheads, white supremacists, and "some South African extremist groups".[250]

The neo-Nazi Russian National Unity group's branch in Estonia is officially registered under the name "Kolovrat" and published an extremist newspaper in 2001 under the same name.[251] A criminal investigation found the paper included an array of racial epithets. One Narva resident was sentenced to one year in jail for distribution of Kolovrat.[252] The Kolovrat has since been used by the Rusich Battalion, a Russian militant group known for its operation during the war in Donbas.[253][254] In 2014 and 2015, members of the Ukrainian Azov Regiment were seen with swastika tattoos.[255][256][257][258]

- Flag of the American Nazi Party

- Logo of the National Socialist Movement (U.S.)

- Logo of the Russian National Unity

Western misinterpretation of Asian use

Since the end of the 20th century, and through the early 21st century, confusion and controversy has occurred when personal-use goods bearing the traditional Jain, Buddhist, or Hindu symbols have been exported to the West, notably to North America and Europe, and have been interpreted by purchasers as bearing a Nazi symbol. This has resulted in several such products having been boycotted or pulled from shelves.

When a ten-year-old boy in Lynbrook, New York, bought a set of Pokémon cards imported from Japan in 1999, two of the cards contained the left-facing Buddhist swastika. The boy's parents misinterpreted the symbol as the right-facing Nazi swastika and filed a complaint to the manufacturer. Nintendo of America announced that the cards would be discontinued, explaining that what was acceptable in one culture was not necessarily so in another; their action was welcomed by the Anti-Defamation League who recognised that there was no intention to offend, but said that international commerce meant that "Isolating [the swastika] in Asia would just create more problems."[78]

In 2002, Christmas crackers containing plastic toy red pandas sporting swastikas were pulled from shelves after complaints from customers in Canada. The manufacturer, based in China, said the symbol was presented in a traditional sense and not as a reference to the Nazis, and apologised to the customers for the cross-cultural mix-up.[259]

In 2020, the retailer Shein pulled a necklace featuring a left-facing swastika pendant from its website after receiving backlash on social media. The retailer apologized for the lack of sensitivity but noted that the swastika was a Buddhist symbol.[260]

Swastika as distinct from Hakenkreuz debate

Beginning in the early 2000s, partially as a reaction to the publication of a book titled The Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption? by Steven Heller,[78] there has been a movement by Hindus, Buddhists, and Native Americans to "reclaim" the swastika as a sacred symbol.[2][261] These groups argue that the swastika is distinct from the Nazi symbol. However, Hitler said that the Nazi symbol was the same as the Oriental symbol. On 13 August 1920, speaking to his followers in the Hofbräuhaus am Platzl of Munich, Hitler said that the Nazi symbol was shared by various cultures around the world, and could be seen "as far as India and Japan, carved in the temple pillars."[262]

The main barrier to the effort to "reclaim", "restore", or "reassess" the swastika comes from the decades of extremely negative association in the Western world following the Nazi Party's adoption of it in the 1920s. As well, white supremacist groups still cling to the symbol as an icon of power and identity.[244]

Many media organizations in the West also continue to describe neo-Nazi usage of the symbol as a swastika, or sometimes with the "Nazi" adjective written as "Nazi Swastika".[263][264] Groups that oppose this media terminology do not wish to censor such usage, but rather to shift coverage of antisemitic and hateful events to describe the symbol in this context as a "Hakenkreuz" or "hooked cross".[265]

See also

- Arevakhach – Ancient Armenian national symbol

- Borjgali – Georgian symbol of the Sun

- Brigid's cross – Cross woven from rushes, arms offset

- Camunian rose – Prehistoric symbol from the petroglyphs of Valcamonica

- Fasces – Bound bundle of wooden rods, sometimes with an axe

- Fascist symbolism – Use of certain images and symbols which are designed to represent aspects of fascism

- Flash and circle – Symbol of the British Union of Fascists

- Fylfot – Anglo-Saxon symbol and swastika variation

- Lauburu – Basque cross

- Nazi symbolism – Symbols used by Nazis and neo-Nazis

- Sun cross – Circle containing four or more spokes

- Svastikasana – Ancient seated meditation posture in hatha yoga

- Triskelion – Symbol with three-fold rotational symmetry

- Tursaansydän – Ancient symbol used in Northern Europe

- Ugunskrusts – The swastika as a symbol in Latvian folklore

- Valknut – Germanic multi-triangular symbol, occurs in several forms

- Yoke and arrows – Badge of Spanish monarchy, fascist emblem

- Z (military symbol) – sometimes called a Zwastika

Notes

- ^ In a broader sense, swastika is a rosette with any number of rays bent in one direction,[9] such as triskelion or arevakhach.

- ^ Except for religious use.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Swastika". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Campion, Mukti Jain (23 October 2014). "How the world loved the swastika – until Hitler stole it". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Buxton, David Roden (1947). "The Christian Antiquities of Northern Ethiopia". Archaeologia. 92. Society of Antiquaries of London: 11 & 23. doi:10.1017/S0261340900009863.

- ^ a b Olson, Jim (September 2020). "The Swastika Symbol in Native American Art". Whispering Wind. 48 (3): 23–25. ISSN 0300-6565. ProQuest 2453170975 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Bruce M. Sullivan (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Scarecrow Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-4616-7189-3.

- ^ a b c d Adrian Snodgrass (1992). The Symbolism of the Stupa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5.

- ^ a b Cort, John E. (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-513234-2.

- ^ a b c Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1-932476-03-3 – via Google Books.[page needed]

- ^ "Свастика" [Swastika]. Большая российская энциклопедия/Great Russian Encyclopedia Online (in Russian). 2017. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "The Migration of Symbols Index". sacred-texts.com.