Origins of the Eighty Years' War

The origins of the Eighty Years' War are complicated, and have been a source of disputes amongst historians for centuries.[1]

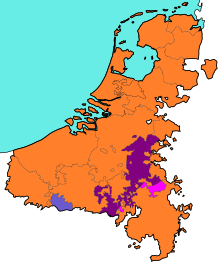

The Habsburg Netherlands emerged as a result of the territorial expansion of the Burgundian State in the 14th and 15th centuries. Upon extinction of the Burgundian State in 1477/1482, these lands were inherited by the House of Habsburg, whose Charles V became both King of Spain[a] and Holy Roman Emperor. By conquering the rest of what would become the "Seventeen Provinces" during the Guelders Wars (1502–1543), and seeking to combine these disparate regions into a single political entity, Charles aspired to counter the Protestant Reformation and keep all his subjects obedient to the Catholic Church.

King Philip II of Spain, in his capacity as sovereign of Habsburg Netherlands, continued the anti-heresy and centralisation policies of his father Charles V. Resistance grew among the moderate nobility and population (both Catholic and dissenting) of the Netherlands.[b] This mood first led to peaceful protests (as from the Compromise of Nobles), but the summer of 1566 erupted in violent protests by Calvinists, known as the iconoclastic fury, or (Dutch: Beeldenstorm) across the Netherlands. The Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, Margaret of Parma, as well as lower authorities, feared insurrection and made further concessions to the Calvinists (such as designation of churches for Calvinist worship), but in December 1566 and early 1567 the first actual battles between Calvinist rebels and Habsburg governmental forces took place, in what would become known as the Eighty Years' War.[2]

Background

[edit]Burgundian and Habsburg territorial expansion

[edit]In a series of marriages and conquests, a succession of dukes of Burgundy expanded their original territory by adding to it a series of fiefdoms, including the Seventeen Provinces.[3] Under the Burgundians (and their Habsburg successors), their holdings in the Low Countries were formally referred to as "De landen van herwaarts over" and in French "Les pays de par deçà". Translated, the phrases mean "those lands around here" for the Dutch and "those lands around there" for the French.[citation needed]

The death of Burgundian duke Charles the Bold during the Battle of Nancy (5 January 1477) created an instant crisis for the Burgundian State. He had no male heirs, and the French and Swiss immediately invaded his lands, starting the War of the Burgundian Succession (1477–1482/93). The Duchy of Burgundy itself was lost to France in 1477, but the Burgundian Netherlands were still intact when Charles of Habsburg, heir to the Netherlands via his grandmother Mary, was born in Ghent in 1500. Charles was raised in the Netherlands and spoke fluent Dutch, French, and Spanish, along with some German.[4] In 1506, he became lord of the Netherlands. In 1516, he inherited the kingdoms of Spain, which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the Americas, and in 1519, he inherited the Archduchy of Austria. Finally, he was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1530.[5] Although Frisia and Guelders offered prolonged resistance under Grutte Pier and Charles of Egmond respectively during the Guelders Wars (1502–1543), virtually all of the Netherlands had been incorporated into the Habsburg domains by the early 1540s.[citation needed]

Habsburg centralisation

[edit]

The shifting balance of power in the late Middle Ages meant that besides the local nobility, many of the Dutch administrators by now were not traditional aristocrats; they were from non-noble families that had risen in status over previous centuries. By the 15th century, Brussels had thus become the de facto capital of the Seventeen Provinces. Dating to the Middle Ages, the districts of the Netherlands, represented by its nobility and the wealthy city-dwelling merchants, had a large measure of autonomy in appointing administrators. The first meeting of the States General of the Netherlands occurred in 1464 during the reign of Philip the Good. On 11 February 1477, the States-General managed to force Mary of Burgundy to grant them the Great Privilege, a collection of rights and privileges that the Burgundian dukes and duchesses were supposed to respect. Charles V and Philip II set out, by contrast, to improve management of the empire by increasing the authority of the central government, in matters like law and taxes.[6] This caused suspicion among the nobility and the merchant class; for example in the city of Utrecht in 1528, when Charles V supplanted the council of guild masters governing the city, installing his own stadtholder, who took worldly powers in the whole province from the archbishop of Utrecht. Charles then ordered the construction of the heavily fortified castle of Vredenburg for defence against the Duchy of Gelre and to control the citizens of Utrecht.[7]

By the time of the governorship of Mary of Hungary (1531–1555), traditional power had largely been removed from both the stadtholders of the provinces and the high noblemen, replaced by professional jurists in the Council of State.[8]

Taxation

[edit]Flanders had long been a very wealthy region, coveted by French kings. The other regions of the Netherlands had also grown wealthy and entrepreneurial.[9] Charles V's empire had become a worldwide empire with large American and European territories. The latter were, however, distributed throughout Europe, which made control and defense difficult. The realm was almost continuously at war with its neighbors in the European heartlands, most notably against France in the Italian Wars, and fought the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean Sea. Other wars were fought against Protestant princes in Germany. The Dutch paid heavy taxes to fund these wars,[10] but saw them as unnecessary and sometimes downright harmful because they were against their most important trading partners.[citation needed]

Protestant Reformation

[edit]During the 16th century, Protestantism rapidly gained ground in northern Europe, including the Anabaptism of the Dutch reformer Menno Simons and the teachings of foreign Protestant leaders like Martin Luther and John Calvin. Dutch Protestants, after initial repression, were tolerated by local authorities.[11] By the 1560s, the Protestant community had gained significant influence in the Netherlands, though still as a minority.[12] In a society dependent on trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Nevertheless, Charles V, and from 1555 his successor Philip II, felt it was their duty to defeat Protestantism,[5] which was branded a heresy by the Catholic Church and viewed as a threat to the entire political system. On the other hand, the intensely moralistic Dutch Protestants insisted their theology, sincere piety, and humble lifestyle was morally superior to what they considered the luxurious habits and superficial religiosity of the ecclesiastical nobility.[13] Harsh suppression led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. Although Philip failed in his attempts to introduce the Spanish Inquisition directly, the Inquisition of the Netherlands (existed until 1566) was nevertheless sufficiently severe and arbitrary to provoke fervent dislike.[14] In the second half of the century, the situation escalated to rebellion, and troops were sent to crush resistance and make the Netherlands Catholic once again.

Events and developments

[edit]Abdication of Charles V as Philip II becomes king (1555–1559)

[edit]When Emperor Charles V began the gradual abdication of his several crowns in October 1555, his son Philip II took over as overlord of the conglomerate of duchies, counties and other feudal fiefs known as the Habsburg Netherlands. Technically they formed the Burgundian Circle that, under the Transaction of Augsburg of 1548 and Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, was to be transferred as a unit in hereditary succession in the House of Habsburg. At the time, this was a personal union of seventeen provinces with little in common beyond their overlord and a constitutional framework painfully assembled during the preceding reigns of Burgundian and Habsburg rulers. This framework divided power between city governments and local nobility, provincial States and royal stadtholders, and a central government of three collateral councils – the Council of State, Privy Council and Council of Finances – assisting (usually) a Regent, and the States-General of the Netherlands. The balance of power was heavily weighted toward the local and regional governments. Like his predecessors, Philip II had to ceremonially affirm those constitutional documents (like the Joyous Entry of Brabant) before his accession to the ducal throne. Beyond these constitutional guarantees, the balance of power between local and central government was guaranteed by the dependence of the central government on extraordinary levies (Beden) granted by the States-General when ordinary tax revenues fell short of the financing requirements of the central government (which occurred frequently, due to the many wars Charles waged).[15]

In 1556 Charles passed on his throne to his son Philip II of Spain.[5] Charles, despite his harsh actions, had been seen as a ruler sympathetic to the needs of the Netherlands. Philip, on the other hand, was raised in Spain and spoke neither Dutch nor French.[citation needed]

Though he was in the Netherlands in January, 1556, Philip II did not assume the reins of government in person, as he had to divide his attentions between England (where he was king-consort of Mary I of England), the Netherlands, and Spain. He therefore appointed a governor-general Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, and subsequently from 1559 on, a Regent (his half-sister Margaret of Parma) to lead the central government on a day-to-day basis. As in the days of Charles V, these regents governed in close cooperation with Netherlandish grandees, such as William, Prince of Orange, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn, and Lamoral, Count of Egmont. But (other than Charles) he also introduced a number of non-Netherlandish councillors into the Council of State, foremost Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, a cardinal from Franche-Comté. These people gained a preponderant influence in the Council, much to the chagrin of the Netherlandish old guard.[citation needed]

Increasing Spanish influence in the Netherlands (1559–1561)

[edit]

When Philip left for Spain in 1559 (as it turned out, permanently) the central government experienced political strains, and these were exacerbated by questions of religious policy. Like his father, Philip was a fervent enemy of the Protestant teachings of Martin Luther, John Calvin, and the Anabaptists. Charles had legally defined heresy as "treason against God" (or French lèse-majesté divine) an "exceptional crime" that was outside the purview of normal legal procedures in the Netherlands. He outlawed heresy in special placards that made it a capital offence, to be prosecuted by a Netherlandish version of the Inquisition. Between 1523 and 1566, more than 1,300 people were executed as heretics, far more relative to the overall population than, for instance, in France.[16]

The anti-Protestant placards, and the policy of repression of heresy in general, were highly unpopular, not just with prospective adherents of the Protestant faiths, but also with the Catholic population and the local governments, who considered it an intrusion on their prerogatives. Towards the end of Charles' reign, enforcement had become quite lax, but Philip insisted on rigorous enforcement, and this caused more and more popular unrest. In the province of Holland, for instance, there were riots in the late 1550s during which the mob freed some condemned persons before their execution.[17]

To support and strengthen the Counter-Reformation that began with the Council of Trent, Philip launched a wholesale organizational reform of the Catholic Church in the Netherlands in 1559, with Papal approval. Fourteen new dioceses replaced the old three, and were headed by Granvelle as archbishop of the new archdiocese of Mechelen. The reform was especially unpopular with the old church hierarchy as the new one was to be financed by transfer of a number of rich abbeys that were traditionally in the gift of the high aristocracy. The new bishops were then to take the lead in enforcement of the anti-heresy placards, and intensify the Inquisition.[18]

In an effort to build a stable and trustworthy government of the Netherlands, Philip appointed his half-sister Margaret of Parma as governor.[5] He continued his father's policy of appointing members of the high nobility of the Netherlands to the Raad van State (Council of State), the governing body of the seventeen provinces that advised the governor. He made his confidant Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle head of the council. However, in 1558 the States of the provinces and the States-General of the Netherlands already started to contradict Philip's wishes by objecting to his tax proposals. They also demanded, with eventual success, the withdrawal of Spanish troops left by Philip to guard the Southern Netherlands' border with France; seeing them as a threat to their own independence (1559–1561).[19]

League of Netherlandish nobles against Granvelle (1561–1564)

[edit]

Subsequent reforms met with much opposition, mainly directed at Granvelle. In 1561, the ten most powerful Netherlandish noblemen formed the League against Granvelle.[20][21] The core of the League was the triumvirate of Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Horne, and William "the Silent", Prince of Orange, later joined by Berghes, Montigny, Megen, Mansfeld, Hoogstraten, Philippe, Count of Ligne and Hachicourt.[21] All ten Ligueurs were knights in the Order of the Golden Fleece, and almost all of them were stadtholders. High noblemen who opposed the League, and thus more or less backed Granvelle, were inter alia Philippe III de Croÿ (Aarschot), Guillaume de Croy, Marquis de Renty, Charles de Berlaymont and Jean de Ligne, Duke of Arenberg.[21]

Petitions to King Philip by the high nobility went unanswered. Some of the most influential nobles, including Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn, and William the Silent, withdrew from the Council of State until Philip recalled Granvelle.[5]

Granvelle's perceived aggrandizement helped focus the opposition against him, and the grandees under the leadership of Orange engineered his recall in 1564. Emboldened by this success Orange intensified his attempts to engineer religious toleration. He persuaded Margaret and the Council to ask for a moderation of the placards against heresy. Philip delayed his response, however, and opposition against his religious policies gained more widespread support.

In late 1564, the nobles noted the growing power of the reformation and urged Philip to devise realistic measures to prevent violence. Philip answered that sterner measures were the only answer. Subsequently, Egmont, Horne, and Orange withdrew once more from the council, and Bergen and Meghem resigned their Stadholdership. Meanwhile, religious protests were increasing despite increased oppression.

Growing religious tensions (1564–1566)

[edit]

Philip finally rejected the request for policy moderation in his Letters from the Segovia Woods of October 1565. In response, a group of members of the lesser nobility, among whom were Louis of Nassau, a younger brother of Orange, and the brother's John and Philip of St. Aldegonde, prepared a petition for Philip that sought the abolition of the Inquisition. This Compromise of Nobles was supported by about 400 aristocrats, both Catholic and Protestant, and was presented to Margaret on 5 April 1566. Impressed by the massive support for the compromise, she suspended the placards, awaiting Philip's final ruling.[22]

One of Margaret's courtiers, Count Berlaymont, called the presentation of this petition an act of "beggars" (French "gueux"), a name then taken up by the petitioners themselves (they called themselves the Geuzen).

Beeldenstorm and outbreak of war

[edit]

The period between the start of the Beeldenstorm in August 1566 until early 1572 (before the Capture of Brielle on 1 April 1572) contained the first events of a series that would later be known as the Eighty Years' War between the Spanish Empire and disparate groups of rebels in the Habsburg Netherlands.[c] Some of the first pitched battles and sieges between radical Calvinists and Habsburg governmental forces took place in the years 1566–1567, followed by the arrival and government takeover by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba (simply known as "Alba" or "Alva") with an army of 10,000 Spanish and Italian soldiers. Next, an ill-fated invasion by the most powerful nobleman of the Low Countries, the exiled but still-Catholic William "the Silent" of Orange, failed to inspire a general anti-government revolt. Although the war seemed over before it got underway, in the years 1569–1571, Alba's repression grew severe, and opposition against his regime mounted to new heights and became susceptible to rebellion.

Although virtually all historians place the start of the war somewhere in this period, there is no historical consensus on which exact event should be considered to have begun the war. Consequently, there is no agreement whether the war really lasted exactly eighty years. For this and other reasons, some historians have endeavoured to replace the name "Eighty Years' War" with "Dutch Revolt", but there is also no consensus either to which period the term "Dutch Revolt" should apply (be it the prelude to the war, the initial stage(s) of the war, or the entire war).[24]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Constitutionally, the Crowns of Castile and Aragon would not be united into the Kingdom of Spain until the 1707–1716 Nueva Planta decrees, and Charles formally reigned as Charles I of Castile and Aragon (sometimes informally called "Spain"). But in historiography, he is more commonly known as Emperor Charles V.

- ^ Unless otherwise indicated, "Netherlands" and "Netherlandish" refer here to the entire area of the Habsburg Netherlands and its inhabitants (including modern Belgium, Luxembourg and parts of northern France, but excluding areas such as the Principality of Liège), whereas "Dutch Republic" and "Dutch" will refer to the country, currently known as the Netherlands, and its inhabitants.

- ^ "...the starting phase of the Revolt in Zeeland. We label the 1566–1572 period as the strike up to the Revolt: years in which the resistance against central authority, grown out to a rebellion, began to powerfully manifest itself."[23]

References

[edit]- ^ "Tachtigjarige Oorlog §1. Historische problematiek". Encarta Encyclopedie Winkler Prins (in Dutch). Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum. 1993–2002.

- ^ "Tachtigjarige Oorlog §1. Historische problematiek". Encarta Encyclopedie Winkler Prins (in Dutch). Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum. 1993–2002.

- ^ Huizinga, Johan (1997). The Autumn of the Middle Ages (Dutch edition—Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen) (26th (1st—1919) ed.). Olympus. ISBN 90-254-1207-6.

- ^ Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain, 1469–1714: a society of conflict (3rd ed.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-78464-6.

- ^ a b c d e Geyl 2001.

- ^ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ^ de Bruin, R. E.; T. J. Hoekstra; A. Pietersma (1999). The city of Utrecht through twenty centuries: a brief history (1st ed.). SPOU and the Utrecht Archief; Utrecht Nl. ISBN 90-5479-040-7.

- ^ Van Nierop, H., "Alva's Throne—making sense of the revolt of the Netherlands". In: Darby, G. (ed), The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt (Londen/New York 2001) pp. 29–47, 37

- ^ Jansen, H. P. H. (2002). Geschiedenis van de Middeleeuwen (in Dutch) (12th (1st—1978) ed.). Het Spectrum. ISBN 90-274-5377-2.

- ^ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 132–134. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ^ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ^ R. Po-chia Hsia, ed. A Companion to the Reformation World (2006) pp 118–34

- ^ R. Po-chia Hsia, ed. A Companion to the Reformation World (2006) pp 3–36

- ^ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ^ Koenigsberger 2007, p. 184–92.

- ^ Tracy 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Tracy 2008, p. 68.

- ^ Tracy 2008, p. 68–69.

- ^ G. Parker, The Dutch Revolt. Revised edition (1985), 46.

- ^ Soen, Violet (2012). Vredehandel : Adellijke en Habsburgse verzoeningspogingen tijdens de Nederlandse Opstand (1564-1581). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9789089643773. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Geevers, L. (2011). Gevallen vazallen: de integratie van Oranje, Egmont en Horn in de Spaans-Habsburgse monarchie (1559-1567). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9789048520763. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ Tracy 2008, p. 69–70.

- ^ Rooze-Stouthamer 2009, p. 11–12.

- ^ "Tachtigjarige Oorlog §1. Historische problematiek". Encarta Encyclopedie Winkler Prins (in Dutch). Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum. 1993–2002.

Bibliography

[edit]- van Gelderen, M. (2002). The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt 1555–1590. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89163-9.

- Geyl, Pieter (2001). History of the Dutch-Speaking peoples 1555–1648 (1sr (combines two volumes from 1932 and 1936) ed.). London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-225-8.

- Glete, J. (2002). War and the State in Early Modern Europe. Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States, 1500–1660. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22645-7.

- Israel, Jonathan (1989). Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821139-2.

- Israel, Jonathan (1990). Empires and Entrepôts: The Dutch, the Spanish Monarchy, and the Jews, 1585–1713. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1-85285-022-1.

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-873072-1.

- Koenigsberger, Helmut G. (2007). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments. The Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-04437-0. [2001] paperback

- Parker, Geoffrey (2004). The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road 1567–1659. Second edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54392-7. paperback

- Rooze-Stouthamer, Clasina Martina (2009). De opmaat tot de Opstand: Zeeland en het centraal gezag (1566–1572) (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9789087040918.

- Tracy, J.D. (2008). The Founding of the Dutch Republic: War, Finance, and Politics in Holland 1572–1588. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920911-8.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch