Rakovica Monastery

Rakovica monastery | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Манастир Раковица |

| Order | Serbian Orthodox |

| Established | 14th century |

| Dedicated to | Archangels Michael and Gabriel |

| Diocese | Archbishopric of Belgrade and Karlovci |

| Site | |

| Location | Between Resnik and Rakovica |

| Public access | Yes |

The Rakovica Monastery (Serbian: Манастир Раковица, romanized: Manastir Rakovica) is the monastery of the Serbian Orthodox Church, within the Archbishopric of Belgrade and Karlovci, located in the municipality of Rakovica in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is dedicated to the archangels Michael and Gabriel.[1]

Mentioned in the 16th century, the Rakovica Monastery is the oldest holy object in Belgrade, where the regular service is still being held.[2]

The central part of the coat of arms of the Rakovica municipality is occupied by the representation Rakovica monastery.

Location

[edit]The Rakovica Monastery is located at 34 Patrijarha Dimitrija Street. It is situated on the eastern slopes of the 209-metre-high (686 ft) Straževica hill, 11 km (6.8 mi) south from downtown Belgrade. The monastery is in the valley of the Rakovički Creek, between the Straževica, on the west, and Pruževica hills, on the east. It is surrounded by the neighborhoods of Resnik (south), Sunčani Breg (east), Miljakovac III (northeast), Miljakovac (north) and Kneževac and Kijevo (west).[3][4][5][6]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]

According to the folk tradition, the monastery named Rakovica was built in the early 14th century, during the reigns of either king Dragutin or king Milutin, who allegedly were also the ktetors. However, there are no historical records that can confirm that. The earliest written mention of the monastery was found in the travel accounts of Feliks Petančić from 1502, under the title of "Ranauicence monasterium". Later on it is also mentioned in the Ottoman sources, in the census register from 1560, among other churches and monasteries around Belgrade.[1][3] The Memorial, written much later by the monks, mentions king Dragutin as the ktetor.[7]

However, it was predated by an older monastery which was not called Rakovica and which celebrated the Dormition of the Mother of God. The monastery apparently was a big one, having church, konaks and a metochion. It seems to be an important religious location as the monks from other monasteries often gathered here. The church was called Crkva Prevelika. The monastery named Rakovica was located further to the east, above the village of Rakovica (modern Belgrade's neighborhood of Selo Rakovica, not to be confused with the neighborhood of Rakovica where the monastery is today, which is also part of Belgrade). It was situated on the foothills of the Avala mountain, between the villages of Rakovica and Vrčin. The monastery celebrated Holy Archangel Michael.[1][2] The location of the old monastery in 1560 was confirmed by the Ottoman sources as being near the "village of Hrčin" (Vrčin). It is believed that on this new location, there was a prior church, called the Magnificent Church. According to the myth, the icons themselves selected the new location, as at night they would leave the old monastery on their own, and move to the new location.[7]

Located on the unfavorable place, in the vicinity of the major crossroads and settlements, the monastery was destroyed during the Ottoman advances towards Vienna in 1592 and the national riots in 1594. Because of that and due to constant robbing, the monks relocated to its present location, deeper into the forest. The remains of the old building on its original location in Selo Rakovica (the traces of the walls, the column of the honorable table, etc.) were found.[1][2] The location is across the modern IKEA department store. People still gather on the location during the church slavas, or major feast days like Dormition of the Mother of God or Archangels' Day, even though there is no cross on the lot. No archaeological survey has been done to explore what is located below the ground.[7]

The original Rakovica monastery was mentioned in the charter of the Wallachian Duke Constantin Brâncoveanu Besaraba, from 1701,[8] which says that the monastery was erected and built from the scratch by a good Christian, the late duke Radula, who was the lord of this country (Wallachia). It is assumed that it was the voivode Radu I of Wallachia, Prince Lazar's son-in-law.,[1][9] which would place the period of the rebuilding in the 1370s or the 1380s,[3] as Radul ruled from 1377 to 1385. Besaraba donated 100 "large chunks" of salt to the monastery.[7]

There is also a myth that the original monastery was founded by Miloš Obilić in the late 14th century. After the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, the Ottomans burned the monastery down. Only in the 15th century, a local resident named Raka reconstructed the monastery, which was then named after him.[7]

17th to 19th century

[edit]Around year 1600, construction of the Church of the Holy Archangel Michael began. Later, the entire monastery complex developed around it.[7]

Part of the monastic brotherhood joined their fellow Serbs in territories now part of Austria during the Great Migrations of the Serbs in 1690, bringing with them relics and books. Monk Grigorije, from the monastery, played an important role in the diplomatic efforts bringing to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, between Austria and Ottoman Empire. Doing various favors to the Russian side, the monastery received numerous gifts, including money, church books, icons, etc. The monastery had a joint administration with the Tresije Monastery on the Kosmaj mountain, and apparently was quite affluent at the time, as it was able to finance the reconstruction of the Tresije.[3]

Soon, more wars broke out (Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718), Austro-Turkish War (1737–1739)) and the clergy supported the Austrian side. As Serbia remained under the Ottoman rule after 1739, as a result, the clergy and the local population fled to Austria, with almost all relics from the monastery because the monastery was destroyed once more. They settled in the Velika Remeta Monastery, in the Syrmia region. The Ottomans later allowed for a group of monks to return to Rakovica. On 14 September 1739, the merger of Rakovica and Veliki Remeta under one administration was proclaimed. However, as the two monasteries were in two different states, the union never came through and Rakovica continued as a sole monastery. In 1768 Amvrosije Janković painted numerous icons. The wars ended with the Austro-Turkish war of 1788–1791, when the monastery was destroyed again, as the clergy again supported Austrians, so the Ottomans burned it in retaliation, while the abbot of the monastery of that time, Sofronije, was hanged on the elm tree in front of the monastery. The process of slow renovation began.[1][3]

The monastery was damaged in both the First and the Second Serbian Uprising, 1804–1813 and 1815, respectively. The monks took active participation in the rebellion against the Ottomans.[6]

The most important for the reconstruction of the monastery was the ruling prince Miloš Obrenović (1815–1839; 1858–1860), who buried his infant son in Rakovica. The prince financed construction of the monastic cells, the grand dining room and one of the konaks. The monastery was also helped by Miloš' wife Ljubica Obrenović and his sister-in-law, Tomanija Obrenović.[3] It is now that Tomanija financed construction of the belfry and one of the konaks. Due to he heavy involvement of the royals, Rakovica was called "court's monastery".[7]

20th and 21st century

[edit]

In 1905 the Monastic school started to work in the monastery, the first of that kind in Serbia. For its needs in 1925 the new building was erected, the so-called "Plato's konak". The building was designed by the Russian architect Valery Staševski in the Serbo-Byzantine Revival style. The school was active until 1932, when it was transferred to the Visoki Dečani monastery in Metohija.[3]

The monastery avoided the damaging in both World Wars. During World War II, Patriarch Gavrilo for a short period was held in detention in Rakovica by the occupational German army.[6] Until the war, area around the monastery was one of the main excursion sites of the Belgraders. Partially because the area was heavily forested with an old ("ancient"), thick forest, and partially because of the artificial Lake Kijevo. During the war both the forest and the lake disappeared: the forest was cut while the lake was drained from 1941 to 1947.[10]

From 1947, Rakovica was the seat of the Orthodox theology faculty of the Serbian Orthodox Church. In 1958 the faculty was relocated to the newly finished educational facilities, including the campus, in the part of the Karaburma neighborhood, which today became known after the Serbian name for the seminary, Bogoslovija. As the new location of Bogoslovija was previously a hospital for the children with mycosis, the children were relocated to the Rakovica monastery. The hospital was later moved out but during the existence, the church was fenced by the wire from the konak.[2]

Patriarch German decided to turn the monastery into a female one, or convent, in 1959. He acquired the sewing machines so the abbesses sewed the clothes and garments to support the monastery.[2]

During the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999, in the process of constant, everyday heavy bombing of the Straževica hill, the monastery was damaged, especially the front wall of the old church, that is, its front wall was damaged again.[6][11][12]

In 2002, the church of the Dormition of the Mother of God was built within the complex.[6]

In 2007 at the old building location, the archaeological researches were done, and then again from 16 July till 16 August 2008, with the aim of confirming the assumption that the building in question is actually the old monastery building. The report states that the required results "were missing", and that the "existence of medieval necropolis in this area, as well as the remains of the honourable table...indicate the existence of the sacral object in that area, although its material remains have not been asserted so far."[13]

Though open for visits, after the burial of Patriarch Pavle in 2009, in order to preserve the peace in the complex, the weddings and baptisms are no longer performed in the monastery.[2]

Religious complex

[edit]As it comprises a growing number of religious edifices, the religious complex has been referred to as the Rakovica Athos. Within the yard of the monastery are the churches of Archangel Michael and Dormition of the Mother of God, while other objects are located just outside of it.[14]

Church of the Holy Archangel Michael (16th century)

[edit]

Central church, around which complex developed in time.[7]

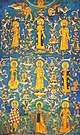

Nowadays within the monastery complex are located facilities made in different historical periods, from the 15th to the 20th century. Certainly, the most important facility is the Church of Holy Archangels Michael and Gabriel. The period of the construction of the monastery church cannot be precisely dated, but it is placed in a wider interval between the restoration of the Serbian Orthodox church as the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in 1557, and the Great Migrations of the Serbs in 1690. It was designed as a one-nave building in a three-conched plan, with the visible influence of the Morava architectural school. The church has two domes, the larger one over the central arcade of the nave, and the smaller over the narthex. Basically, the nave is resolved in the form of a reduced inscribed cross, although this form is not visible in the external treatment. Interventions on the church from the 18th and 19th century altered substantially the authentic look of the upper part of the building. During the 1861 reconstruction, the upper section was added while the roof tiles were replaced with the sheet metal. Horizontal division on the facade, was performed using cordoned cornice, separating upper and lower zone into two unequal parts. In general, the church façade resembles little its original structure especially since it has been covered with plaster.[3][15]

Iconostasis was originally made of the wall partition with two central icons of Jesus Christ and Mother Mary, whereas on other places varies wooden and canvas icons were hanged. However, in 1862, the new iconostasis was set up, of the smaller dimensions, whose construction was financed by the Prince of Serbia Mihailo Obrenović.[1] The iconostasis has elements of Classicism and the Baroque woodcut. The icons were replaced in the early 20th century. They were painted by Rafailo Momčilović. Old icons, gift from the Russian emperor Peter the Great after 1699, were in the monastery at least until 1737. They were then taken by the monks to the Velika Remeta Monastery. During World War II, the Ustaše forces plundered the monastery and took, among everything else, the icons to Zagreb. Today, they are kept in the Galery of Matica Srpska.[3]

Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God (2002)

[edit]Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God, or as it is called Velika Gospojina among Serbs, was added to the complex in 2002. Velika Gospojina, observed on 28 August, is the official slava of the monastery. Thus, the church was officially opened on 28 August 2002.[6] It is located across the old church.[2]

Church of Annunciation (2015)

[edit]As monastery was searching for the solution for its steady water supply, hegumenia Mother Evgenija said that if they found the sufficiently abundant water source, the church would be built on the location. Water was discovered at the depth of 100 m (330 ft), on the slopes of the Zmajevac Hill in the neighborhood of Miljakovac. The source supplies the entire monastery with water, and the small church dedicated to the Annunciation was finished in 2015 next to it.[14]

Church of the Saint Nicholas of Myra (2019)

[edit]In March 2018 a construction of another church within the complex began. Located 100 m (330 ft) from the monastery gates, it will be dedicated to the Saint Nicholas of Myra. It is expected that the construction will be finished by October 2018 and the interior by 19 December, which is when the Saint Nicholas feast day is observed by the Serbian Orthodox Church. As numerous ill and old visit the monastery, it was decided to build a church at the foothill and close to the road (crkva krajputašica, "road church").[2][16]

The small church covers an area of 110 m2 (1,200 sq ft) and was projected by architect Olivera Dobrijević. One of the conditions by the clergy was that the church could be built only from the natural materials which can be obtained in Serbia. Hence, it is mainly built with bricks, the windows are made of oak, the floor is paved with the natural stone while the roof is covered with copper sheets. The grayish granite from the Bukulja mountain and white marble from Venčac (for the altar) have been used. The façade of the church is predominantly in the Moravian style, with influences from the Raška architectural school. The interior is partially covered in mosaics, work of Đuro Radlović, representing Saint Nicholas, Jesus Christ, Mother of God, Saint Sava and Saint Petka. The sculptural ornaments (rosettes, etc.) are done by Miloš Komad, also from white marble.[14][2][16]

First service in the church was held on 19 November 2018, Saint Nicholas Day. The still unfinished church was opened for the congregation for Easter, on 21 April 2019. It was consecrated by the Serbian Patriarch Irinej on 23 November 2019. Wedding ceremonies will be allowed in the church, as opposed to the other parts of the complex.[14][16]

Chapel of Saint Petka

[edit]Across the monastery, there is a natural water spring Svetka Petka, named after the Parascheva of the Balkans, with small chapel.[2] The chapel is sometimes simply called Svetinja ("holy relic"), and the folk myths claim the water has healing powers.[7]

Hermitage of Saint Sava

[edit]Until the early 20th century, there was a small hermitage or anchorite cell (isposnica) above the monastery. It was a small chapel, called the Hermitage of Saint Sava.[3]

Other objects

[edit]

The monastery includes the konaks (Knežev, Ljubičlin, Platonov).[1][3] There are also a minute park and a drinking fountain within the complex.[6] The drinking fountain was designed by Jovan Ilkić.[7] The complex also contains a vineyard.[2] There is monument to Vasa Čarapić, along the north outer wall. It was dedicated in 1910, and sculptured by Kosta Jovanović. On the western wall, there is a memorial plaque with the names of soldiers who died in the 1912-1913 Balkan wars.[7]

Burial sites

[edit]A number of important historical and religious figures or the members of the royal Obrenović dynasty are buried within the monastery complex.

Son of the ruling prince Miloš Obrenović, Todor, who died as a baby in 1830, was buried in the monastery. It was the reason why Miloš supported the renewal of the monastery during his reign, so as his successor, and Todor's brother, Mihailo Obrenović.[1] One section of the monastery was named after Miloš' wife Ljubica, the so-called Ljubica's konak,[1] which is not to be confused with her quarters with the same name in downtown Belgrade's Kosančićev Venac neighborhood, the Princess Ljubica's Residence. Members of the royal family are mostly buried in the chapel, in the right section of the churchyard. Others include Miloš' brother Jevrem Obrenović, his wife Tomanija Bogićević Obrenović (1796–1881) and Milivoje Blaznavac, a military general and prime minister of Serbia, who was married to Jevrem's and Tomanija's granddaughter Katarina. Simka Obrenović (1818–37), Jevrem's and Tomanija's daughter, is buried next to the church dedicated to the archangel Michael.[2] The monastery became a sort of a mausoleum for Jevrem's family, as his and Tomanija's children and grandchildren were also buried there.[7]

On the other, northern side of the church, one of the leaders of the First Serbian Uprising, Vasa Čarapić, was buried. Also close to the church are the tombs of two Serbian Orthodox Church patriarchs, Dimitrije (in 1930) and Pavle (in 2009). Patriarch Pavle specifically asked to be buried in the Rakovica Monastery and his tomb became sort of a pilgrimage site as it is toured by numerous visitors.[1][2][17] The tombstone is in the shape of the cross made of white marble with the inscriptions "Patriarch Pavle" on one, and "I await the resurrection of the dead" on the other side.[6]

The monastery also keeps the holy relics of the Saint hieromartyrs Procopius of Scythopolis and Theodore of Tyre, Saint Nectarios of Aegina and the particle of the True Cross. They were donated to the monastery by the Patriarch German who brought them from his visit to Jerusalem in 1959.[6]

Religious life

[edit]On 19 December 1909, the Saint Nicholas feast day, Nikolaj Velimirović took his monastic vows in the monastery. Elder Tadej (Thaddeus) of Vitovnica, better known as Elder Tadej Štrbulović was sent to the school of iconography in the monastery right after he became a monk. He was ordained into the rank of hieromonk on 3 February 1938 in the Rakovica monastery.[3]

Today, Rakovica is a female monastery. As of 2018, the hegumenia is Mother Evgenija. Both the abbesses and the novices live in the complex.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lazić, Jovana (15 June 2007). "Manastir Rakovica". Orthodoxy magazine.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Branka Vasiljević (26 August 2018). "Gradi se nova crkva ispred rakovičkog manastira" [New church in front of the Rakovica Monastery is being built]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Manastir Rakovica" [Rakovica Monastery] (in Serbian). Manastiri u Srbiji. 2017.

- ^ Tamara Marinković-Radošević (2007). Beograd - plan i vodič. Belgrade: Geokarta. ISBN 978-86-459-0006-0.

- ^ Beograd - plan grada. Smedrevska Palanka: M@gic M@p. 2006. ISBN 86-83501-53-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Radenka Marković (March 2018). "Oaza mira i duhovnosti" [Oasis of peace and spirituality] (in Serbian). Beogradski Glas.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Branka Vasiljević (26 April 2022). "Čuvar vere u nedrima Straževice i Pruževice" [Keeper of the faith in the bosoms of Straževica and Pruževica]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ Branko Vujović, The Church Monuments in the City of Belgrade, Belgrade 1973. pp. 259–260.

- ^ "Rakovica – Belgrade, Culture, Standing conference of the cities and municipalities, retrieved on 15 November 2009

- ^ Goran Vesić (10 January 2019). Где су се Београђани некада одмарали [Where Belgraders used to rest]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ^ "NATO agresija 1999", The City of Belgrade, retrieved on 15 November 2009

- ^ "Godišnjica NATO bombardovanja Srbije, 24. mart 2005", 24 March 2005, retrieved on 15 November 2009

- ^ "Lokalitet stari manastir Rakovica". Cultural Heritage Protection Institute of the City of Belgrade, retrieved on 15 November 2009

- ^ a b c d Branka Vasiljević (23 November 2019). "Crkva Svetog Nikole Mirlikijskog – nova krajputašica" [Church of the Saint Nicholas of Myra - new road church]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Branko Vujović, Church Monuments in the City of Belgrade, Belgrade 1973, pp. 267–268; Aleksandar Božović, Manastir Rakovica, Belgrade 2010

- ^ a b c Branka Vasiljević (27–28 April 2019). "У комплексу Раковичког манастира - Завршен храм Светог Николе Мирликијског" [Within the Rakovica Monastery complex - Temple of the Saint Nicholas of Myra finished]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ^ Tihi odlazak duhovnog vođe, Blic, 15 November 2009. Retrieved on 15 November 2009.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch