Robert M. La Follette

Robert M. La Follette | |

|---|---|

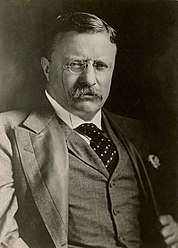

La Follette after 1905 | |

| United States Senator from Wisconsin | |

| In office January 4, 1906 – June 18, 1925 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph V. Quarles |

| Succeeded by | Robert M. La Follette Jr. |

| 20th Governor of Wisconsin | |

| In office January 7, 1901 – January 1, 1906 | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Preceded by | Edward Scofield |

| Succeeded by | James O. Davidson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Wisconsin's 3rd district | |

| In office March 4, 1885 – March 3, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Burr W. Jones |

| Succeeded by | Allen R. Bushnell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Marion La Follette June 14, 1855 Primrose, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | June 18, 1925 (aged 70) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Hill Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Other political affiliations | Progressive (1924) |

| Spouse | Belle Case |

| Children | 4, including Robert Jr., Philip, and Fola |

| Education | University of Wisconsin–Madison (BS) |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism |

|---|

|

Robert Marion La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855 – June 18, 1925), nicknamed "Fighting Bob", was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the governor of Wisconsin from 1901 to 1906. A Republican for most of his life, he ran for president of the United States as the nominee of his own Progressive Party in the 1924 U.S. presidential election. Historian John D. Buenker describes La Follette as "the most celebrated figure in Wisconsin history".[1][2]

Born and raised in Wisconsin, La Follette won election as the Dane County District Attorney in 1880. Four years later, he was elected to the House of Representatives, where he was friendly with party leaders like William McKinley. After losing his seat in the 1890 election, La Follette regrouped. As a populist, he embraced progressivism and built up a coalition of disaffected Republicans. He sought election as governor in 1896 and 1898 before winning the 1900 gubernatorial election. As governor of Wisconsin, La Follette compiled a progressive record, implementing primary elections and tax reform.

La Follette won re-election in 1902 and 1904, but in 1905 the legislature elected him to the United States Senate. His populist base was energized when he emerged as a national progressive leader in the Senate, often clashing with conservatives like Nelson Aldrich. He initially supported President William Howard Taft, but broke with Taft after the latter failed to push a reduction in tariff rates. He challenged Taft for the Republican presidential nomination in the 1912 presidential election, but his candidacy was overshadowed by that of former President Theodore Roosevelt. La Follette's refusal to support Roosevelt alienated many progressives, and although La Follette continued to serve in the Senate, he lost his stature as the leader of that chamber's progressive Republicans. La Follette supported some of President Woodrow Wilson's policies, but he broke with the president over foreign policy. During World War I, La Follette was one of the most outspoken opponents of the administration's domestic and international policies and was against the war.

With the Republican and Democratic parties each nominating conservative candidates in the 1924 presidential election, left-wing groups coalesced behind La Follette's third-party candidacy. With the support of the Socialist Party, farmer's groups, labor unions, and others, La Follette briefly appeared to be a serious threat to unseat Republican President Calvin Coolidge. La Follette stated that his chief goal was to break the "combined power of the private monopoly system over the political and economic life of the American people",[3] and he called for government ownership of railroads and electric utilities, cheap credit for farmers, the outlawing of child labor, stronger laws to help labor unions, protections for civil liberties, and a 10-year term for members of the federal judiciary. His complicated alliance was difficult to manage, and the Republicans came together to win the 1924 election. La Follette won 16.6% of the popular vote, one of the best third party performances in U.S. history. He died shortly after the presidential election, but his sons, Robert M. La Follette Jr. and Philip La Follette, succeeded him as progressive leaders in Wisconsin.

Early life

[edit]

Robert Marion La Follette Sr. was born on a farm in Primrose, Wisconsin, on June 14, 1855. He was the youngest of five children born to Josiah La Follette and Mary Ferguson, who had settled in Wisconsin in 1850.[4] Josiah descended from French Huguenots, while Mary was of Scottish ancestry.[5] La Follette's great-great-grandfather, Joseph La Follette emigrated from France to New Jersey in 1745. La Follette's great-grandfather moved to Kentucky, where they were neighbors to the Lincoln family.[6]

Josiah died just eight months after Robert was born,[4] and in 1862, Mary married John Saxton, a wealthy, seventy-year-old merchant.[7] La Follette's poor relationship with Saxton made for a difficult childhood.[8] Though his mother was a Democrat, La Follette became, like most of his neighbors, a member of the Republican Party.[9]

La Follette began attending school at the age of four, though he often worked on the family farm. After Saxton died in 1872, La Follette, his mother, and his older sister moved to the nearby town of Madison.[10] La Follette began attending the University of Wisconsin in 1875 and graduated in 1879 with a Bachelor of Science degree.[11][12] He was a mediocre student, but won a statewide oratory contest and established a student newspaper named the University Press.[11] He was deeply influenced by the university's president, John Bascom, on issues of morality, ethics, and social justice.[8] During his time at the university, he became a vegetarian, declaring that his diet gave him more energy and a "clear head".[13]

La Follette met Belle Case while attending the University of Wisconsin, and they married on December 31, 1881,[4] at her family home in Baraboo, Wisconsin. She became a leader in the feminist movement, an advocate of women's suffrage and an important influence on the development of La Follette's ideas.[8]

Early political career

[edit]House of Representatives

[edit]La Follette was admitted to the state bar association in 1880.[12] That same year, he won election as the district attorney for Dane County, Wisconsin, beginning a long career in politics. He became a protégé of George E. Bryant, a wealthy Republican Party businessman and landowner from Madison.[14] In 1884, he won election to the House of Representatives, becoming the youngest member of the subsequent 49th Congress.[15] His political views were broadly in line with those of other Northern Republicans at the time; he supported high tariff rates and developed a strong relationship with William McKinley.[16] He did, however, occasionally stray from the wishes of party leaders, as he voted for the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 and the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.[17] He also denounced racial discrimination in the Southern United States and favored the Lodge Bill, which would have provided federal protections against the mass disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South.[18] Milwaukee Sentinel referred to him as being "so good a fellow that even his enemies like him".[4] Views on racial and ethnic matters were not central to La Follette's political thinking. His wife was a stronger proponent of civil rights.[19]

At 35 years old, La Follette lost his seat in the 1890 Democratic landslide. Several factors contributed to his loss, including a compulsory-education bill passed by the Republican-controlled state legislature in 1889. Because the law required major subjects in schools to be taught in English, it contributed to a divide between the Catholic and Lutheran communities in Wisconsin. La Follette's support for the protective McKinley Tariff may have also played a role in his defeat.[20] After the election, La Follette returned to Madison to begin a private law practice.[8] Author Kris Stahl wrote that due to his "extraordinarily energetic" and dominating personality, he became known as "Fighting Bob" La Follette.[6]

Gubernatorial candidate

[edit]

In his autobiography, La Follette explains that he experienced a political epiphany in 1891 after Senator Philetus Sawyer attempted to bribe him. La Follette claimed that Sawyer offered the bribe so that La Follette would influence his brother-in-law, Judge Robert G. Siebecker, who was presiding over a case involving state funds that Republican officials had allegedly embezzled. La Follette's public allegation of bribery precipitated a split with many friends and party leaders, though he continued to support Republican candidates like John Coit Spooner.[21] He also strongly endorsed McKinley's run for president in the 1896 election, and he denounced Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan as a radical.[22] Rather than bolting the party or retiring from politics, La Follette began building a coalition of dissatisfied Republicans, many of whom were relatively young and well-educated.[23] Among his key allies were former governor William D. Hoard and Isaac Stephenson, the latter of whom published a pro-La Follette newspaper.[24] La Follette's coalition also included many individuals from the state's large Scandinavian population, including Nils P. Haugen, Irvine Lenroot, and James O. Davidson.[25]

Beginning in 1894, La Follette's coalition focused on winning the office of Governor of Wisconsin. With La Follette serving as his campaign manager, Haugen sought the Republican nomination for governor in 1894, but he was defeated by William H. Upham.[26] La Follette ran for the Republican gubernatorial nomination in 1896, but he was beaten by Edward Scofield; La Follette alleged that Scofield only won the nomination after conservative party leaders bribed certain Republican delegates. La Follette declined to run as an independent despite the pleas of some supporters, and after the election, he turned down an offer from President William McKinley to serve as the Comptroller of the Currency.[27] In 1897, La Follette began advocating the replacement of party caucuses and conventions, the traditional method of partisan nominations for office, with primary elections, which allowed voters to directly choose party nominees.[28] He also denounced the power of corporations, charging that they had taken control of the Republican Party.[29] These progressive stances had become increasingly popular in the wake of the Panic of 1893, a severe economic downturn that caused many to reevaluate their political beliefs.[30]

La Follette ran for governor for the second time in 1898, but he was once again defeated by Scofield in the Republican primary.[31] In 1900, La Follette made a third bid for governor, and won the Republican nomination, in part because he reached an accommodation with many of the conservative party leaders. Running in a strong year for Republicans nationwide, La Follette decisively defeated his Democratic opponent Louis G. Bomrich in the general election, winning just under 60 percent of the vote.[32]

Governor of Wisconsin (1901–1906)

[edit]

Upon taking office, La Follette called for an ambitious reform agenda, with his two top priorities being the implementation of primary elections[33] and a reform of the state's tax system.[34][35] La Follette initially hoped to work with the conservative faction of the Republican Party to pass these reforms, but conservatives and railroad interests broke with the governor. La Follette vetoed a primary election bill that would have applied only to local elections, while the state Senate voted to officially censure the governor after he attacked the legislature for failing to vote on his tax bill.[36] Conservative party leaders attempted to deny La Follette renomination in 1902, but La Follette's energized supporters overcame the conservatives and took control of the state convention, implementing a progressive party platform. In the 1902 general election, La Follette decisively defeated the conservative Democratic nominee, Mayor David Stuart Rose of Milwaukee.[37]

In the aftermath of the 1902 election, the state legislature enacted the direct primary (subject to a statewide referendum) and La Follette's tax reform bill. The new tax law, which required railroads to pay taxes based on property owned rather than profits, resulted in railroads paying nearly double the amount of taxes they had paid before the enactment of the law.[38] Having accomplished his first two major goals, La Follette next focused on regulating railroad rates, but the railroads prevented passage of his bill in 1903.[39] During this period, La Follette became increasingly convinced of the need for a direct income tax in order to minimize tax avoidance by the wealthy.[40] During his governorship, La Follette appointed African-American William Miller for a position in his office.[41]

After the legislature adjourned in mid-1903, La Follette began lecturing on the Chautauqua circuit, delivering 57 speeches across the Midwest.[42] He also earned the attention of muckraker journalists like Ray Stannard Baker and Lincoln Steffens, many of whom supported La Follette's progressive agenda.[43] La Follette's continued movement towards progressivism alienated many Republican Party leaders, and La Follette's followers and conservative party leaders held separate conventions in 1904; ultimately, the state Supreme Court declared that La Follette was the Republican Party's 1904 gubernatorial nominee.[44] In the general election in Wisconsin that year, La Follette won 51 percent of the vote, but he ran far behind Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who took 63 percent of the Wisconsin's vote in the national election by comparison. In that same election, Wisconsin voters approved the implementation of the direct primary.[45]

During the 1904 campaign, La Follette pledged that he would not resign as governor during his term, but after winning re-election he directed state representative Irvine Lenroot, a close political ally, to secure his election to the United States Senate.[46] Shortly after La Follette delivered the inaugural message of his third term as governor, Lenroot began meeting with other legislators to assure that La Follette would be able to win election to the Senate; at that time, the state legislature elected senators.[47] La Follette was formally nominated by the Republican caucus on January 23, 1905, and the state legislature chose him the following day.[48] La Follette delayed accepting the nomination and continued to serve as governor until December 1905, when he announced his resignation.[49][33] Throughout 1905, La Follette continued to push his progressive policies, including the state regulation of railroad rates. The state legislature passed a relatively weak regulation bill that La Follette considered vetoing, but he ultimately signed the law.[50] Lieutenant Governor James O. Davidson succeeded La Follette as governor and went on to win re-election in 1906.[51]

Senator (1906–1925)

[edit]Roosevelt administration (1906–1909)

[edit]

La Follette immediately emerged as a progressive leader in the Senate. At first, he focused on a railroad regulation bill making its way through the Senate;[35] he attacked the bill, eventually known as the Hepburn Act, as a watered-down compromise.[52] He also began campaigning across the country, advocating for the election of progressive senators.[53] Conservative party leaders, including Spooner and Nelson W. Aldrich, detested La Follette, viewing him as a dangerous demagogue. Hoping to deprive La Follette of as much influence as possible, Aldrich and his allies assigned La Follette to insignificant committees and loaded him down with routine work.[54] Nonetheless, La Follette found ways to attack monopolistic coal companies, and he pressed for an expansion of the railroad regulation powers of the Interstate Commerce Committee.[55]

With the help of sympathetic journalists, La Follette also led the passage of the 1907 Railway Hours Act, which prohibited railroad workers from working for more than 16 consecutive hours.[56] Though he initially enjoyed warm relations with President Roosevelt, La Follette soured somewhat on the president after Roosevelt declined to support some progressive measures like physical valuation of Railroad properties. When Roosevelt did not support La Follette's bill to withdraw mineral land from corporate exploitation, La Follette told to Belle that Roosevelt "throws me down every day or so".[57] Meanwhile, La Follette alienated some of his supporters in Wisconsin by favoring Stephenson, his main donor, over Lenroot in an election to fill the seat of retiring Senator John Coit Spooner.[58] After the Panic of 1907, La Follette strongly opposed the Aldrich–Vreeland Act, which would authorize the issuance of $500 million in bond-backed currency. He alleged that the panic had been engineered by the "Money Trust", a group of 97 large corporations that sought to use the panic to destroy competitors and force the government to prop up their businesses.[59] La Follette was unable to prevent the passage of the bill, but his 19-hour speech, the longest filibuster in Senate history up to that point, proved popular throughout the country.[60]

Beginning in 1908, La Follette repeatedly sought election as the president.[33][61] La Follette hoped that the backing of influential journalists like Lincoln Steffens and William Randolph Hearst would convince Republican leaders to nominate him for president in 1908, but he was unable to build a strong base of support outside of Wisconsin.[62] Though he entered the 1908 Republican National Convention with the backing of most Wisconsin delegates, no delegates outside of his home state backed his candidacy.[63] At the start of the convention, Secretary of War William Howard Taft was President Roosevelt's preferred choice, but Taft was opposed by some conservatives in the party. La Follette hoped that he might emerge as the Republican presidential nominee after multiple ballots, but Taft won the nomination on the first ballot of the convention.[63] La Follette was nonetheless pleased that the party platform called for a reduction of the tariff and that Taft indicated that he would emulate Roosevelt's support for progressive policies. Taft defeated William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 election, and several progressives were victorious in the concurrent congressional elections.[64] In early 1909, La Follette launched La Follette's Weekly Magazine, which quickly achieved a circulation of well over 30,000.[65] An early associate editor of the magazine was the writer Herbert Quick.[66] In March 1924, La Follette contributed to the appointment of African-American Walter I. Cohen as Comptroller of the Port of New Orleans.[67]

Battling the Taft administration (1909–1913)

[edit]Along with Jonathan P. Dolliver, La Follette led a progressive faction of Republicans in the Senate that clashed with Aldrich over the reduction of tariff rates. Their fight for tariff reduction was motivated by a desire to lower prices for consumers, as they believed that the high rates of the 1897 Dingley Act unfairly protected large corporations from competition and thereby allowed those corporations to charge high prices.[68] Despite a widespread desire among consumers for lower prices, and a party platform that called for tariff reduction, Aldrich and other party leaders put forward the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act, which largely preserved the high tariff rates of the Dingley Act. With the support of President Taft, the Payne–Aldrich Tariff passed the Senate; all Republican senators except for La Follette's group of progressives voted for the tariff. The progressives did, however, begin the process of proposing the Sixteenth Amendment, which would effectively allow the federal government to levy an income tax.[69]

In late 1909, Taft fired Louis Glavis, an official of the Department of the Interior who had alleged that Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger favored the illegal expansion of coal mining on government land in Alaska. The resulting Pinchot–Ballinger controversy pitted Ballinger and Taft against Gifford Pinchot, the head of the United States Forest Service and a close friend of Theodore Roosevelt. La Follette's progressives strongly criticized the Taft administration for its handling of the controversy and initiated a congressional investigation into the affair.[70]

La Follette's successful re-election campaign in early 1911 further bolstered his position as the leader of the progressive faction of the Republican Party.[71] In January 1911, after consulting with sympathetic journalists and public officials, La Follette launched the National Progressive Republican League, an organization devoted to passing progressive laws such as primary elections, the direct election of U.S. senators, and referendums. La Follette hoped that the league would also form a base of support for a challenge against Taft for the 1912 Republican presidential nomination.[72] The league won the endorsement of nine senators, 16 congressmen, four governors, and well-known individuals such as Pinchot and Louis Brandeis, but notably lacked the support of former President Roosevelt. Explaining his refusal to join the league, Roosevelt asserted that he viewed the organization as too radical, stating his "wish to follow in the path of Abraham Lincoln rather than in the path of John Brown and Wendell Phillips".[72]

By mid-1911, most progressives believed that the battle for the 1912 Republican nomination would be waged between La Follette and Taft, but La Follette himself feared that Roosevelt would jump into the race. Many progressive leaders strongly criticized La Follette for focusing on writing his autobiography rather than on campaigning across the country.[73] La Follette believed that his autobiography would help him win votes,[73] and said: "Every line of this autobiography is written for the express purpose of exhibiting the struggle for a more representative government which is going forward in this country, and to cheer on the fighters for that cause."[74] Roosevelt announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination in early 1912, but La Follette rejected the request of Pinchot and some other progressive leaders to drop out of the race and endorse the former president.

In Philadelphia on February 2, 1912, La Follette delivered a disastrous speech to the Periodical Publishers Banquet. He spoke for two hours before an audience of 500 nationally influential magazine editors and writers.[75][76] Congressman Henry Cooper, a friend and ally of the senator, was there and made a memorandum:

La Follette killed himself politically by his most unfortunate (worse than that) speech. It was a shocking scene. He lost his temper repeatedly—shook his fist—at listeners who had started to walk out too tired to listen longer—was abusive, ugly in manner....From the very outset his speech was tedious, inappropriate (for a banquet occasion like that), stereotyped; like too many others of his [it was] extreme in matter and especially in manner....LaFollette's secretary, came over to me…and with a dejected, disgusted look said softly to me—"This is terrible—he is making a d___d fool of himself." It ends him for the Presidency.[77]

Most of the audience decided La Follette had suffered a mental breakdown, and most of his supporters shifted to Roosevelt. La Follette's family said he was distraught after learning that his daughter, Mary, required surgery. She recovered but his candidacy did not.[78] Nonetheless, La Follette continued to campaign, focusing his attacks on Roosevelt rather than Taft.[79]

La Follette hoped to rejuvenate his campaign with victories in the 1912 Republican primaries,[12] but was able to win in only Wisconsin and North Dakota.[80] He continued to oppose Roosevelt at the 1912 Republican National Convention, which ultimately re-nominated Taft. Roosevelt's supporters bolted the Republican Party, established the Progressive Party, and nominated Roosevelt on a third party ticket. La Follette continued to attack Roosevelt, working with conservative Senator Boies Penrose, with whom La Follette shared only a dislike of Roosevelt, to establish a committee to investigate the sources of contributions to Roosevelt's 1904 and 1912 campaigns.[81] A filibuster threat by La Follette helped secure the passage of the enabling resolution.[82] La Follette otherwise remained neutral in the three-way general election contest between Roosevelt, Taft, and the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson. With the Republican Party split, Wilson emerged triumphant in the 1912 election. La Follette's conduct during the campaign destroyed his standing as the leader of progressive Republicans in the Senate, as many progressives believed that La Follette's refusal to work with Roosevelt had damaged the progressive cause and abetted Taft's re-nomination as Republican candidate.[83]

Wilson administration (1913–1921)

[edit]La Follette initially hoped to work closely with the Wilson administration, but Wilson ultimately chose to rely on congressional Democrats to pass legislation. Nonetheless, La Follette was the lone Republican senator to vote for the Revenue Act of 1913, which lowered tariff rates and levied a federal income tax. La Follette, who wanted to use the income tax for the purpose of income redistribution, influenced the bill by calling for a higher surtax on those earning more than $100,000 per year.[84] La Follette and his fellow progressives challenged Wilson's proposed Federal Reserve Act as being overly-friendly towards the banking establishment, but Wilson convinced Democrats to enact his bill.[85] La Follette also clashed with Southern Democrats like James K. Vardaman, who directed the farm benefits of the Smith–Lever Act of 1914 away from African-Americans.[86] In 1915, La Follette won passage of the Seamen's Act, which allowed sailors to quit their jobs at any port where cargo was unloaded; the bill also required passenger ships to include lifeboats.[87]

In the 1914 mid-term elections, La Follette and his progressive allies in Wisconsin suffered a major defeat when conservative railroad executive Emanuel L. Philipp won election as governor.[88] La Follette fended off a primary challenge in 1916 and went on to decisively defeat his Democratic opponent in the general election, but Philipp also won re-election.[89] By 1916, foreign policy had emerged as the key issue in the country, and La Follette strongly opposed American interventions in Latin America.[90] After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, La Follette praised the Wilson administration's policy of neutrality, but he broke with the president as Wilson pursued policies favorable to the Allied Powers.[91] Theodore Roosevelt called him a "skunk who ought to be hanged" when he opposed the arming of American merchant ships.[92]

Opposition to American involvement in World War I

[edit]La Follette opposed United States entry into World War I. On April 4, 1917, the day of the vote on a war declaration by the US Congress, La Follette in a debate before the US Senate said, "Stand firm against the war and the future will honor you. Collective homicide can not establish human rights. For our country to enter the European war would be treason to humanity."[93] Eventually, the U.S. Senate voted to support entry to the war 82–6, with the resolution passing the House of Representatives 373–50 two days later.[94] La Follette faced immediate pushback, including by the Wisconsin State Journal, whose editorial claimed La Follette to be acting on behalf of German interests. The newspaper said, "It reveals his position to be decidedly pro-German (and) un-American... It is nothing short of pathetic to witness a man like La Follette, whose many brave battles for democracy have endeared him to the hearts of hundreds of thousands of Americans, now lending himself to the encouragement of autocracy. And that is all it is".[95] After the U.S. declared war, La Follette denounced many of the administration's wartime policies, including the Selective Service Act of 1917 and the Espionage Act of 1917.[96] This earned the ire of many Americans, who believed that La Follette was a traitor to his country, effectively supporting Germany.[97] It also resulted in a Senate Committee pursuing a vote to expel him from the Senate for disloyalty, due to an antiwar speech he made in 1917; the Committee ultimately recommended against expulsion and the Senate agreed, 50–21, in early 1919.[98]

After the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in late 1917, La Follette supported the Bolsheviks, whom he believed to be "struggling to establish an industrial democracy". He denounced the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War in 1919, which he thought stemmed from Wilson's desire to prevent the spread of socialism.[99] During the First Red Scare, a post-war period in the United States marked by the widespread fear of socialism and anarchism, La Follette condemned the Palmer Raids, sought the repeal of the Espionage Act, and proposed amnesty for political prisoners like Eugene V. Debs.[100] Along with a diverse array of progressive and conservative Republican senators, he helped prevent the U.S. from ratifying the Treaty of Versailles. La Follette believed that the League of Nations, a vital component of the Treaty of Versailles, was primarily designed to protect the dominant financial interests of the United States and the Allied Powers.[101]

Harding–Coolidge administration (1921–1924)

[edit]

La Follette retained influence in Wisconsin after the war, and he led a progressive delegation to the 1920 Republican National Convention. Nationwide, however, the Republican Party had increasingly embraced conservatism, and La Follette was denounced as a Bolshevik when he called for the repeal of the 1920 Esch–Cummins Act. After the Republican Party nominated conservative senator Warren G. Harding, La Follette explored a third-party presidential bid, though he ultimately did not seek the presidency because various progressive groups were unable to agree on a platform.[102] After the 1920 presidential election, which was won by Harding, La Follette became part of a "farm bloc" of congressmen who sought federal farm loans, a reduction in tariff rates, and other policies designed to help farmers.[103] He also resisted the tax cuts proposed by Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, and his opposition helped prevent Congress from cutting taxes as deeply as had been proposed by the secretary of the treasury.[104]

In 1922, La Follette decisively defeated a primary challenge from conservative allies of President Harding, and he went on to win re-election with 81 percent of the vote. Nationwide, the elections saw the defeat of many conservative Republicans, leaving La Follette and his allies with control of the balance of power in Congress.[105] After the Supreme Court struck down a federal child labor law, La Follette became increasingly critical of the Court, and he proposed an amendment that would allow Congress to repass any law declared unconstitutional.[106] La Follette also began investigations into the Harding administration, and his efforts ultimately helped result in the unearthing of the Teapot Dome scandal.[107] Harding died in August 1923 and was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge,[108][109] who was firmly in the conservative wing of the Republican Party.

In 1920–21, La Follette continued his support for the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War, in addition to his vigorous denunciation of imperialism and militarism in that conflict and beyond. In the American and British versions, he continued to oppose the treaty oversight settlement and continued to reject the League of Nations. He advocated self-government for Ireland, India, Egypt, and withdrawal of foreign interest from China. By 1922, he focused primarily on domestic affairs.[110]

1924 presidential campaign

[edit]

By 1924, conservatives were ascendant in both major parties. In 1923, La Follette began planning his final stand for a third party run for the presidency, sending his allies to various states to build up a base of support and ensure ballot access. In early 1924, a group of labor unions, socialists, and farm groups, inspired by the success of Britain's Labour Party, established the Conference for Progressive Political Action (CPPA) as an umbrella organization of left-wing groups. Aside from labor unions and farm groups, the CPPA also included groups representing African Americans, women, and college voters. The CPPA scheduled a national convention to nominate a candidate for president in July 1924.[111] La Follette had changed his previous pro-Bolshevik stance after visiting the Soviet Union in late 1923, where he had seen the impact of Communism on civil liberties and political rights. During that same time, La Follette visited England, Germany and Italy, where he expressed his dismay at the lack of freedom in the press to leader Benito Mussolini.[3] With other left-wing groups supporting La Follette, the Communist Party nominated its first ever candidate for president, William Z. Foster.[112][113]

On July 3, 1924, one day before the CPPA convention, La Follette announced his candidacy in the 1924 presidential election, stating that, "to break the combined power of the private monopoly system over the political and economic life of the American people is the one paramount issue."[3] The CPPA convention, which was dominated by supporters of La Follette, quickly endorsed his presidential bid. La Follette's first choice for his running mate, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court Louis Brandeis, refused to join the campaign. The convention instead nominated Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana, a progressive Democrat who had refused to endorse John W. Davis, the Democratic nominee for president. Though the Socialists pushed for a full slate of candidates, at La Follette's insistence, the CPPA did not establish a formal third party or field candidates for races other than the presidency.[3] La Follette would appear on the ballot in every state except Louisiana, but his ticket was known by a variety of labels, including "Progressive", "Socialist", "Non-Partisan", and "Independent".[114]

After the convention, the Socialist Party of America, acting on the advice of perennial presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, endorsed La Follette's candidacy. The American Federation of Labor and numerous other worker's groups also threw their support behind La Follette. Among the notable individuals who endorsed La Follette were birth control activist Margaret Sanger, African-American leader W. E. B. Du Bois, economist Thorstein Veblen, and newspaper publisher E. W. Scripps. Harold L. Ickes and some other progressives who had supported Roosevelt's 1912 candidacy threw their backing behind La Follette, though others, including Gifford Pinchot, endorsed Coolidge.[3] Another group supporting La Follette was the Steuben Society, a German-American organization that claimed a membership of six million.[115]

La Follette's platform was based on many of the issues that he had been campaigning on throughout his political career.[116] He called for government ownership of the railroads and electric utilities, cheap credit for farmers, the outlawing of child labor, stronger laws to help labor unions, more protection of civil liberties, an end to American imperialism in Latin America, and a referendum before any president could again lead the nation into war.[117]

Professional gamblers initially gave La Follette a 16-to-1 odds of winning, and many expected that his candidacy would force a contingent election in the House of Representatives. As election day approached, however, those hoping for a La Follette victory became more pessimistic. The various groups supporting La Follette often clashed, and his campaign was not nearly as well-financed as those of Davis and especially Coolidge. Corporate leaders, who saw in La Follette the specter of class warfare, mobilized against his third-party candidacy. Republicans campaigned on a "Coolidge or chaos" platform, arguing that the election of La Follette would severely disrupt economic growth.[118] Having little fear of a Democratic victory, the Republican Party mainly focused its campaign attacks on La Follette.[119]

In August and September, La Follette expressed his opposition to the Ku Klux Klan, describing the organization as containing "seeds of death" in its own body and his hatred for immigration quotas on the basis of racial discrimination, while defending control of immigration regarding economic issues. In response to La Follette's statements regarding the Klan, Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley Evans denounced La Follette as being the "arch enemy of the country".[120][121][122]

Ultimately, La Follette took 16.6 percent of the vote, while Coolidge won a majority of the popular and electoral vote. La Follette carried his home state of Wisconsin and finished second in eleven states, all of which were west of the Mississippi River. He performed best in rural areas and working-class urban areas, with much of his support coming from individuals affiliated with the Socialist Party.[123] La Follette's 16.6 percent showing represents the third best popular vote showing for a third party since the American Civil War (after Roosevelt in 1912 and Ross Perot in 1992), and with him winning of his home state of Wisconsin.[117] The CPPA dissolved shortly after the election as various groups withdrew support.[124]

Death and legacy

[edit]

La Follette died in Washington, D.C., of a cardiovascular disease, complicated by bronchitis and pneumonia, on June 18, 1925, four days after his 70th birthday.[125] He was buried in the Forest Hill Cemetery on the near west side of Madison, Wisconsin.[126] After his death, his Senate seat was offered to his wife, Belle Case La Follette, but she declined the offer.[127] Subsequently, his son Robert M. La Follette Jr. was elected to the seat.[127]

After her husband's death, Belle Case remained an influential figure and editor. By the mid-1930s, the La Follettes had reformed the Progressive Party on the state level in the form of the Wisconsin Progressive Party. The party quickly, if briefly, became the dominant political power in the state, electing seven Progressive congressmen in 1934 and 1936. Their younger son, Philip La Follette, was elected Governor of Wisconsin, while their older son, Robert M. La Follette Jr., succeeded his father as senator. La Follette's daughter, Fola La Follette, was a prominent suffragette and labor activist and was married to the playwright George Middleton. A grandson, Bronson La Follette, served several terms as the Attorney General of Wisconsin and was the 1968 Democratic gubernatorial nominee. La Follette has also influenced numerous other progressive politicians outside of Wisconsin, including Floyd B. Olson, Upton Sinclair, Fiorello La Guardia, and Wayne Morse.[117] Senator and 2020 presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has frequently been compared to La Follette.[128]

In 1957, a Senate Committee chaired by Senator John F. Kennedy selected La Follette to be one of the five senators to be listed in the Senate "Hall of Fame", along with Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, and Robert A. Taft.[129] A 1982 survey asking historians to rank the "ten greatest Senators in the nation's history" based on "accomplishments in office" and "long range impact on American history", placed La Follette first, tied with Henry Clay.[130] Writing in 1998, historian John D. Buenker described La Follette as "the most celebrated figure in Wisconsin history".[2] La Follette is represented by one of two statues from Wisconsin in the National Statuary Hall. An oval portrait of La Follette, painted by his cousin, Chester La Follette, also hangs in the Senate.[131] The Robert M. La Follette House in Maple Bluff, Wisconsin, is a National Historic Landmark. Other things named for La Follette include La Follette High School in Madison, the Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the town of La Follette, Wisconsin. Socialist historian Gabriel Kolko saw La Follette as "standing apart from many Progressives in favoring competition, not monopoly (private or public)."[132]

The Fighting Bob Festival is an annual September tribute event held by Wisconsin progressives, sponsored by The Progressive and The Capital Times.[133] It was founded in 2001 by Wisconsin labor lawyer and activist Ed Garvey. The Chautauqua-inspired Fighting Bob Fest has been held in Baraboo, Madison, La Crosse, Milwaukee,[134][135] and Stevens Point.[136] Speakers have included Wisconsin figures like Rep. Mark Pocan, former Sen. Russ Feingold, Sen. Tammy Baldwin and journalist John Nichols, other noted mid-westerners, as well as national progressive populist figures, like Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, Jim Hightower, Nina Turner[137] and Jesse Jackson.[138]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Buenker (2013), p. 490.

- ^ a b Buenker (1998), p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e Thelen (1976), pp. 182–184.

- ^ a b c d Ritchie (2000)

- ^ Buenker (1998), p. 5.

- ^ a b Stahl (2020), p. 23–24.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d Buhle et al. (1994), pp. 159–166.

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 2.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Buenker (1998), p. 6.

- ^ a b c Collier's New Encyclopedia (1921)

- ^ Wheeler et al. (1913), p. 1199.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 1.

- ^ New International Encyclopædia (1905)

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 8–10.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 10–11.

- ^ Brøndal (2011), p. 344–346.

- ^ Unger (2000), pp. 95–97.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 9–11.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Buenker (1998), p. 15.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 17–19.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 21–23

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 22–25.

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 25–29.

- ^ a b c Encyclopædia Britannica (1922)

- ^ Buenker (1998), pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Americana (1920)

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 37–39.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 29, 39.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 47.

- ^ La Follette and the Negro; A Consistent Record of 35 Years, From 1889 to 1924

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 41.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Margulies (1976), pp. 214–217.

- ^ Margulies (1976), pp. 218–219.

- ^ Margulies (1976), pp. 220–221.

- ^ Margulies (1976), pp. 221–225.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 45–46.

- ^ Margulies (1976), pp. 223–225.

- ^ Margulies (1997), pp. 267–268.

- ^ Margulies (1997), pp. 268–269.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 55–57.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 58–60.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 62.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 62–64.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Margulies (1997), p. 259.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Margulies (1997), pp. 278–279.

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 67.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth (1982). The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 337.

- ^ La Follette and the Negro; A Consistent Record of 35 Years; From 1889 to 1924

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 69–71.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 71–74.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Thelen (1976), pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b Thelen (1976), pp. 87–89.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 88.

- ^ Nancy C. Unger, "The 'Political Suicide' of Robert M. La Follette: Public Disaster, Private Catharsis" Psychohistory Review 21#2 (1993) pp. 187-220 online.

- ^ Nancy C. Unger, Fighting Bob La Follette (2000) pp. 204-216.

- ^ Robert S. Maxwell, ed., '’La Follette’’ (1969) pp. 112-113.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 90–93.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 93.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 93–95.

- ^ Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard Taft, Vol. II, pp.829-830, (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1939).

- ^ Richmond Evening Journal, Vol.8, No.76, Aug. 26, 1912, pp.1 and 7.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 96–98.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 100–102.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 102–103.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 119–120.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 118–119.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 122–124.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 124–127.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 127–129.

- ^ Unger (2000), p. 247.

- ^ Turning Points in Wisconsin History

- ^ The American Year Book (1918), pp. 10–11.

- ^ Wisconsin State Journal

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 135–136.

- ^ Ryan (1988), p. 1.

- ^ "Expulsion Case of Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin (1919)". Official Website of the United States Senate. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 148–149.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 149–150.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 150–152.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 163–164.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 167–168.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 169–170.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 172–173.

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 175–176.

- ^ The Evening Independent (1923)

- ^ The Victoria Advocate (1923)

- ^ Jentleson and Paterson (ed.) (1997), p. 37–38

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 180–182.

- ^ Shideler (1950), p. 446.

- ^ Mussolini and the Italian People; The Progressive, Robert M. La Follette Jr.

- ^ Shideler (1950), p. 452.

- ^ Shideler (1950), pp. 446–448.

- ^ Shideler (1950), p. 445.

- ^ a b c Dreier (2011)

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 185–190.

- ^ Shideler (1950), pp. 449–450.

- ^ "La Follette Scores the Ku Klux Klan; Asserts He Is Opposed to Any Discrimination Between Races, Classes and Creeds. Says it Cannot Survive; He Insists, However, That the Great Issue Is Breaking of the Power of Private Monopoly". The New York Times. Washington (published August 9, 1924). August 8, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved May 6, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ The Progressive Movement of 1924, Kenneth Campbell MacKay, 1966

- ^ Jewish Daily Bulletin, September 15, 1924

- ^ Thelen (1976), pp. 190–192.

- ^ Thelen (1976), p. 100.

- ^ The New York Times (1925)

- ^ Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- ^ a b Wisconsin Historical Society

- ^ Feinman (2016)

- ^ "The 'Famous Five'" – United States Senate

- ^ McLaurin and Pederson (1987), p. 110.

- ^ Robert M. La Follette – United States Senate

- ^ "Forgetting Jefferson". April 24, 2014.

- ^ Hightower, Jim (November 12, 2016). "For the Love of Fighting Bob". Progressive.org. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Damos, Tim (June 14, 2011). "Fighting Bob Fest moving to Madison". Wiscnews.com. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ "Annual Fighting Bob Fest Expands Its Horizon". www.publicnewsservice.org. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

Fighting Bob Fest… events in three locations.… tonight in Madison, and then half-day gatherings in Milwaukee and La Crosse. Traditionally, the Fest … had been held in Baraboo.

- ^ jschooley (September 10, 2019). "Fighting Bob Fest coming to Stevens Point". Stevens Point News. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Pyrek, Emily (September 14, 2017). "'Fighting Bob Fest' coming to La Crosse for the first time". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Bybee, Roger (March 2, 2017). "Wisconsin Progressive Giant Ed Garvey's Vital Message". The American Prospect. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

originated in 2001 with Garvey a central founder, is named after the firebrand progressive Robert La Follette Sr.… the festival has attracted many of the nation's most thoughtful progressives, including Sanders, Jim Hightower, Jesse Jackson, Wisconsin Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin

Works cited

[edit]- Brøndal, Jørn (2011). "The Ethnic and Racial Side of Robert M. La Follette Sr". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 10 (3). Society for Historians of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era: 340–53. doi:10.1017/S1537781411000077. JSTOR 23045141. S2CID 163776027.

- Buenker, John D. (1998). "Robert M. La Follette's Progressive Odyssey". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 82 (1): 2–31. JSTOR 4636775.

- Buenker, John D. (2013). The Progressive Era, 1893–1914. Wisconsin Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87020-631-3.

- Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul; Kaye, Harvey J., eds. (1994). The American Radical. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90804-7.

- Dreier, Peter (April 11, 2011). "La Follette's Wisconsin Idea". Dissent Magazine. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- Feinman, Ronald L. (February 6, 2016). "Between Hillary and Bernie: Who's the Real Progressive?". History News Network. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- Jentleson, Bruce W.; Jentleson, Bruce W., eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of U.S. foreign relations. Thomas G. Paterson. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511055-5. OCLC 34557986.

- Margulies, Herbert (1997). "Robert M. La Follette as Presidential Aspirant: The First Campaign, 1908". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 80 (4): 258–279. JSTOR 4636705.

- Margulies, Herbert F. (1976). "Robert M. La Follette Goes to the Senate, 1905". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 59 (3): 214–225. JSTOR 4635046.

- McLaurin, Ann M.; Pederson, William D. (1987). The Rating game in American politics : an interdisciplinary approach. Irvington Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8290-1812-7. OCLC 15196190.

- Ritchie, Donald A. (2000) [1999]. "La Follette, Robert Marion (1855–1925)". American National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0600351.

- Shideler, James H. (June 1950). "The La Follette Progressive Party Campaign of 1924". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 33 (4): 444–457. JSTOR 4632172.

- Thelen, David P. (1976). Robert M. La Follette and the Insurgent Spirit. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-83927-3. OL 5198113M.

- Ryan, Halford Ross (1988). Oratorical Encounters: Selected Studies and Sources of Twentieth Century Political Accusations. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-313-25568-7.

- Stahl, Kris. "Robert M. La Follette, Sr.: A Man Worth Remembering" Torch Magazine (Spring 2020) online

- Unger, Nancy C. "The 'Political Suicide' of Robert M. La Follette: Public Disaster, Private Catharsis" Psychohistory Review 21#2 (1993) pp. 187–220 online.

- Unger, Nancy C. (2000). Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2545-7. OL 51780M.

- Wheeler, Edward Jewitt; Funk, Isaac Kaufman; Woods, William Seaver (May 24, 1913). Notable Vegetarians.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Wickware, Francis Graham, ed. (1918). The American Year Book: A Record of Events and Progress. T. Nelson & Sons. OCLC 1480987.

- "Bob La Follette's big mistake – State Journal editorial from 100 years ago". Wisconsin State Journal. April 8, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- "Belle Case La Follette". Wisconsin Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "La Follette Dies In Capital Home". The New York Times. June 19, 1925. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- "La Follette's speech in the U.S. Senate against the entry of the United States into the World War, April 4, 1917". Turning Points in Wisconsin History. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress . Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- "Nation Mourns Death of Harding; Coolidge Sworn-In at Home of Father". The Evening Independent. August 3, 1923. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- "President Dies Suddenly; Coolidge Inaugurated President Early Today". The Victoria Advocate. August 3, 1923. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- "Robert M. La Follette". United States Senate. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- "The 'Famous Five'". United States Senate. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: - "La Follette, Robert Marion". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Further reading

[edit]- Cooper, John Milton Jr. (Spring 2004). "Why Wisconsin? The Badger State in the Progressive Era". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 87 (3): 14–25. JSTOR 4637084.

- Hale, William Bayard (June 1911). "La Follette, Pioneer Progressive: The Story of "Fighting Bob", the New Master of the Senate and Candidate for the Presidency". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXII: 14591–14600. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- La Follette, Belle Case, and Fola La Follette. Robert M. La Follette, June 14, 1855- June 18, 1925 (1953) vol 1 online; also vol 2 online; very detailed biography by his wife and daughter.

- McCormick, Richard L. "Divergent Courses of La Follette Progressivism." Reviews in American History 6#4 (1978), pp. 530–536 online

- Maxwell, Robert S. "La Follette and the Progressive Machine in Wisconsin." Indiana Magazine of History (1952) 48#1: 55–70. online

- Maxwell, Robert S. La Follette and the Rise of Progressives in Wisconsin (1956) online

- Maxwell, Robert S. ed. La Follette (1969) online, excerpt from primary sources.

- Murphy, William B. "The National Progressive Republican League and the Elusive Quest for Progressive Unity." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 8.4 (2009): 515–543.

- Scroop, Daniel (2012). "A Life in Progress: Motion and Emotion in the Autobiography of Robert M. La Follette". American Nineteenth Century History. 13 (1): 45–64. doi:10.1080/14664658.2012.681944. ISSN 1466-4658. S2CID 143799227.

- Thelen, David Paul (1964). The Early Life of Robert M. La Follette, 1855-1884. University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Thelen, David P. Robert M. La Follette and the insurgent spirit (1976) online

- Thelen, David Paul. The new citizenship: Origins of progressivism in Wisconsin, 1885-1900 (U of Missouri Press, 1972) online.

- Weisberger, Bernard A. (1994). The La Follettes of Wisconsin: Love and Politics in Progressive America. Madison, Wis.: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Yu, Wang. "'Boss' La Follette and the Paradox of the Progressive Movement" Journal of American History (March 2022) 108#4 pp 726–744. online

Primary sources

[edit]- La Follette, Robert M. (1913). La Follette's Autobiography; A Personal Narrative of Political Experiences (PDF) – via Library of Congress.

- La Follette, Robert M. The political philosophy of Robert M. La Follette as revealed in his speeches and writings (1920) online

- La Follette, Robert M. Speech of Senator Robert M. La Follette. Memorandum of information submitted to the Committee on privileges and elections, United States Senate, Sixty-fifth Congress, second session, relative to the resolutions from the Minnesota Commission of public safety, petitioning for proceedings looking to the expulsion of Senator Robert M. La Follette (1918) online

External links

[edit]- The Career of Robert M. La Follette—documentary coverage at the Wisconsin Historical Society

- Statement of Free Speech and the Right of Congress to Declare the Objects of the War

- Statement of Robert La Follette Sr. on Communist Participation in the Progressive Movement, 26 May 1924

- Wisconsin Electronic Reader—Senator La Follette's picture biography

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch