Robert Pickton

Robert Pickton | |

|---|---|

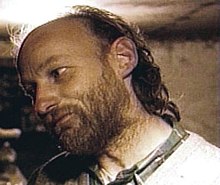

Pickton in 1996 | |

| Born | Robert William Pickton October 24, 1949 Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada |

| Died | May 31, 2024 (aged 74) Quebec City, Quebec, Canada |

| Conviction(s) | Second-degree murder (×6) |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment with no possibility of parole for 25 years |

| Details | |

| Victims | 6 convicted 26 charged 49 confessed |

Span of crimes | 1978–2001 |

| Country | Canada |

Date apprehended | February 22, 2002 |

Robert William Pickton (October 24, 1949 – May 31, 2024), also known as the Pig Farmer Killer or the Butcher, was a Canadian serial killer and pig farmer. After dropping out of school, he left a butcher's apprenticeship to begin working full-time at his family's pig farm, and inherited it in the early 1990s.

Between 1995 and 2001, Pickton is believed to have murdered at least 26 women, many of them prostitutes from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Pickton would confess to 49 murders to an undercover RCMP officer disguised as a cellmate, going on to say he wanted to make it an even 50, but thought he was caught because he got "sloppy".[1][2][3] In 2007, he was convicted on six counts of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole for 25 years—the longest possible sentence for second-degree murder under Canadian law at the time.[4][5]

In 2010, the Crown attorney officially stayed the remaining 20 murder charges, allowing previously unrevealed information to be made available to the public, including that Pickton previously had a 1997 attempted murder charge dropped.[6] Crown prosecutors reasoned that staying the additional charges made the most sense, since Pickton was already serving the maximum sentence allowable.[6]

The discovery of Pickton's crimes sparked widespread outrage and forced the Canadian government to acknowledge the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women,[7] with the British Columbia provincial government forming the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry to examine the role of the police in the matter.[8] Pickton died in 2024 after being attacked in prison by another inmate.[9][10]

Early life and criminal history

[edit]Robert Pickton was born on October 24, 1949,[11] to Leonard Francis Pickton (1896–1977) and Louise Helene Arnal (1912–1979), a family of pig farmers in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, 27 kilometres (17 miles) east of Vancouver. Pickton's older sister, Linda Louise Wright, was sent off to live with relatives in Vancouver as their parents thought that the family pig farm would be an inappropriate setting to raise a young girl. Robert and his younger brother, David Francis Pickton, began working at the farm at an early age, and their mother was very demanding, prioritizing the pigs over the brothers' personal hygiene, and forcing them to work long hours raising the farm's livestock.[12]

Louise often sent the brothers to school in unwashed dirty clothes, reeking of manure and earning them the nickname "stinky piggy" from their classmates. Robert was strongly attached to her and rarely interacted with his abusive father.[13] He struggled in school, being put in a special class after failing grade two.[14] At the age of 12, he began raising a calf which became his beloved pet. Two weeks later, after not finding it after school, he was told to check the barn, and was distraught to find it slaughtered.[15]

Pickton dropped out of school in 1963 and began working as a meat cutter. He continued to do so for nearly seven years before leaving to work full-time at the farm.[16] In 1978 and 1979, the parents died and the siblings inherited the pig farm, selling parts for C$5.16 million. Worker Bill Hiscox called the farm a "creepy-looking place" patrolled by a 612-pound boar and described Pickton as a "pretty quiet guy, hard to strike up a conversation with", whose occasional bizarre behaviour, despite no evidence of substance abuse, would draw attention.[17] Pickton became wealthy by selling parts of his farmland to property developers as the economy of the Lower Mainland grew exponentially in the 1980s–1990s.[18] He often hosted parties at an ad hoc nightclub called Piggy's Palace, which attracted the political and economic elites of the Lower Mainland along with the Hells Angels.[18] Starting in the 1990s, women living in the Lower Mainland, most notably on the impoverished Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, had started to go missing, leading to speculation in the media that a serial killer was operating.[18] The majority of the missing women were Indigenous women, women with substance use disorders, and sex workers.[18]

On March 23, 1997, Pickton was charged with the attempted murder of sex worker Wendy Lynn Eistetter, whom he had stabbed 4 times during an altercation at the farm. She told police he had handcuffed her, and that she had escaped after suffering several lacerations.[17] She told them she had disarmed him and stabbed him with his weapon. He sought treatment at Eagle Ridge Hospital, while Eistetter recovered at the nearest emergency room.

Pickton was released on C$2,000 bond and the attempted-murder charge against him was stayed on January 27, 1998, because Eistetter had drug addiction issues and prosecutors believed her too unstable for her testimony to help secure a conviction. David was convicted of sexual assault in 1992, being fined C$1,000 and given 30 days' probation. In that case the victim told police that David had attacked her in his trailer at the pig farm, but she managed to escape. Robert had also been sued three times for traffic offences in 1988 and 1991, settling all three claims out of court.[17]

The Pickton brothers were eventually sued by Port Coquitlam officials for violating zoning ordinances—neglecting the agriculture for which it had been zoned, and having "altered a large farm building on the land for the purpose of holding dances, concerts and other recreations".[17] They had begun to neglect the site's farming operations and registered a non-profit charity, the Piggy Palace Good Times Society, with the Canadian government in 1996, claiming to "organize, co-ordinate, manage and operate special events, functions, dances, shows and exhibitions on behalf of service organizations, sports organizations and other worthy groups".[17]

Its events included raves and wild parties featuring Vancouver sex workers and gatherings in a converted slaughterhouse on the farm at 953 Dominion Avenue in Port Coquitlam. These events attracted as many as 2,000 people and members of the Hells Angels were known to frequent the farm.[18] Subsequently, the Pickton brothers ignored growing legal pressure and held a 1998 New Year's Eve party, after which they were faced with an injunction banning future parties; the police were "authorized to arrest and remove any person" attending future events at the farm. The society's non-profit status was removed the following year, for inability to produce financial statements. It was subsequently disbanded.[17] An employee of Pickton found several purses belonging to the missing women from the Downtown Eastside and reported Pickton to the police.[18] The police conducted three searches of the farm, but found no evidence.[19] In June 1999, the police received a tip that Pickton had a freezer full of human flesh in his farmhouse, which the police ignored.[20]

Discovery and investigation

[edit]On February 6, 2002, police executed a search warrant for illegal firearms at the Pickton property. Both Pickton brothers were arrested and police obtained a second warrant using what they had seen on the property to search the farm as part of the BC Missing Women Investigation.[21][22] Personal items belonging to missing women were found at the farm, which was sealed off by members of the joint RCMP–Vancouver Police Department task force. The following day, Pickton was charged with weapons offences. Both Picktons were later released and Robert was kept under police surveillance.[23]

On February 22, 2002, Robert Pickton was arrested again and charged with two counts of first degree murder in the deaths of Sereena Abotsway and Mona Wilson.[24] On April 2, three more charges were added for the murders of Jacqueline McDonell, Dianne Rock, and Heather Bottomley. A sixth for the murder of Andrea Joesbury was laid on April 9, followed shortly by a seventh for Brenda Wolfe.[24] On September 20, four more were added for Georgina Papin, Patricia Johnson, Helen Hallmark, and Jennifer Furminger. Another four for Heather Chinnock, Tanya Holyk, Sherry Irving, and Inga Hall were laid on October 3.[24] On May 26, 2005, 12 more came for Cara Ellis, Andrea Borhaven, Debra Lynne Jones, Marnie Frey, Tiffany Drew, Kerry Koski, Sarah de Vries, Cynthia Feliks, Angela Jardine, Wendy Crawford, Diana Melnick, and Jane Doe, bringing the total to 27.[24]

Excavations continued at the farm through November 2003; the cost of the investigation is estimated to have been C$70 million by the end of 2003, according to the provincial government.[25] The property was fenced off under lien by the Crown in Right of British Columbia and remained so as-of 2023.[26][27][28] In the meantime, all the buildings on the property, except a small barn, had been demolished. Forensic analysis proved difficult because the bodies may have been left to decompose, or be eaten by insects and pigs on the farm.

During the early days of the excavations, forensic anthropologists brought in heavy equipment, including two 50-foot (15-metre) flat conveyor belts and soil sifters to find traces of human remains. On March 10, 2004, the government revealed that Pickton may have ground up human flesh and mixed it with pork that he sold to the public; the province's health authority later issued a warning.[29][30][31] Another claim was made that he fed the bodies directly to his pigs.[32] In 2003, a preliminary hearing was held and the clothes and rubber boots that Pickton had been wearing during the Eistetter assault were seized by police from an RCMP storage locker. In 2004, lab testing showed that the DNA of two women (Borhaven and Ellis) were on the items.[33][34][35]

Trial

[edit]Pickton's trial began on January 30, 2006, in New Westminster.[36] Pickton pleaded not guilty to the 27 charges of first-degree murder in the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The voir dire phase of the trial took most of the year to determine what evidence might be admitted before the jury. Reporters were not allowed to disclose any of the material presented in the arguments. On March 17, one of the counts was rejected by Justice James Williams for lack of evidence.[37] On August 9, Justice Williams severed the charges, splitting them into one group of six counts and another of twenty.[38]

The trial proceeded on the group of six counts. The remaining 20 were stayed on August 4, 2010.[6][39][40] Because of the publication ban, full details of the decision were not made publicly available, but Justice Williams explained that trying all 26 charges at once would put an unreasonable burden on the jury as the trial could have lasted up to two years; it would also have increased the possibility of mistrial.[41]

The initial date for the jury trial on the first six counts was January 8, 2007, but it was postponed to January 22.[42][43] On that date, Pickton faced first-degree murder charges in the deaths of Frey, Abotsway, Papin, Joesbury, Wolfe, and Wilson. The media ban was eventually lifted, and the details of what was found during the investigation were publicly released:[44][45][46]

- During Pickton's trial, lab staff testified that about eighty unidentified DNA profiles, roughly half male and half female, have been detected on evidence.[47]

- A loaded .22 revolver with a dildo over the barrel and one round fired, boxes of .357 Magnum handgun ammunition, night-vision goggles, two pairs of faux fur-lined handcuffs, a syringe with three millilitres of blue liquid inside, and "Spanish fly" aphrodisiac were found inside Pickton's trailer. In a videotaped recording played for the jury, Pickton claimed to have attached the dildo to his weapon as a makeshift silencer; this explanation was impractical at best, as revolvers are near-impossible to silence in this manner.[48]

- A videotape of Pickton's friend Scott Chubb saying Pickton had told him a good way to kill a female heroin addict was to inject her with windshield washer fluid. A second tape was played for Pickton, in which an associate named Andrew Bellwood said Pickton mentioned killing sex workers by handcuffing and strangling them, then bleeding and gutting them before feeding them to pigs.

- Photos of the contents of a garbage can found in Pickton's slaughterhouse, which held some remains of victim Mona Wilson.[49]

On December 9, 2007, the jury found Pickton not guilty on six counts of first-degree murder, but he was found guilty on six counts of second-degree murder.[50] On December 11, 2007, after reading eighteen victim impact statements, British Columbia Supreme Court Judge Justice James Williams sentenced Pickton to life with no possibility of parole for 25 years—the maximum punishment for second-degree murder—and equal to the sentence which would have been imposed for a first-degree murder conviction, stating: "Mr. Pickton's conduct was murderous and repeatedly so. I cannot know the details but I know this: What happened to them was senseless and despicable."[51]

Victims

[edit]On December 9, 2007, Pickton was convicted of second-degree murder in the deaths of six women:

- Count One: Sereena Abotsway,[52] 29, reported missing on August 22, 2001

- Count Two: Mona Lee Wilson,[53] 26, reported missing on November 30, 2001

- Count Six: Andrea Joesbury, 22, reported missing June 8, 2001

- Count Seven: Brenda Ann Wolfe,[54] 32, reported missing on April 25, 2000

- Count Eleven: Georgina Faith Papin, 34, reported missing in March 2001

- Count Sixteen: Marnie Lee Anne Frey,[55] 24, reported missing on December 29, 1997

Pickton also stood accused of first-degree murder in the deaths of 21 other women. These charges were stayed on August 4, 2010:[6]

- Count Three: Jacquelene Michelle McDonell,[56] 22, reported missing on January 16, 1999

- Count Four: Dianne Rosemary Rock,[57] 34, reported missing on December 13, 2001

- Count Five: Heather Kathleen Bottomley,[58] 27, reported missing on April 17, 2001

- Count Eight: Jennifer Lynn Furminger, 28, reported missing on December 27, 1999

- Count Nine: Helen Mae Hallmark,[59] 20, reported missing on June 15, 1997

- Count Ten: Patricia Rose Johnson,[60] 25, reported missing on January 2, 2001

- Count Twelve: Heather Gabrielle Chinnock,[61] 30, last seen in April 2001

- Count Thirteen: Tanya Holyk, 23, reported missing on November 3, 1996

- Count Fourteen: Sherry Leigh Irving,[62] 24, reported missing on February 22, 1997

- Count Fifteen: Inga Monique Hall,[63] 46, last seen in February 1998

- Count Seventeen: Tiffany Louise Drew, 27, reported missing on December 31, 1999

- Count Eighteen: Sarah Jean de Vries, 29,[64] last seen in April 1998

- Count Nineteen: Cynthia "Cindy" Feliks,[65] 43, last seen in December 1997

- Count Twenty: Angela Rebecca Jardine, 27, reported missing on November 20, 1998[66][67]

- Count Twenty-One: Diana Melnick, 23,[68] last seen in December 1995

- Count Twenty-Two: Mission Jane Doe, discovered on February 25, 1995

- Count Twenty-Three: Debra Lynne Jones,[69] 42, last seen in December 2000

- Count Twenty-Four: Wendy Crawford, 43, last seen in December 1999

- Count Twenty-Five: Kerry Lynn Koski, 38, reported missing on January 7, 1998

- Count Twenty-Six: Andrea Fay Borhaven, 25,[70] last seen in March 1997

- Count Twenty-Seven: Cara Louise Ellis,[71] 25,[72] reported missing on January 21, 1997

Pickton was implicated in the deaths of but not charged with the murders of three women:

- Mary Ann Clark,[73] 25, disappeared in August 1991.

- Yvonne Marie Boen,[74] 33, reported missing on March 16, 2001

- Dawn Teresa Crey,[75] 42, last seen in December 2000[76][77]

After Pickton was arrested,[78] witness Lynn Ellingsen came forward to authorities claiming to have seen Pickton skinning a woman hanging from a meat hook years earlier and claimed she had not told anyone about it out of fear of losing her life.[79] However, Ellingsen admitted she had blackmailed Pickton about the incident on more than one occasion.[80]

The victims' children filed a civil lawsuit in May 2013 against the Vancouver Police Department, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and the Crown for failing to protect the victims.[81] They reached a settlement in March 2014, and each child was compensated C$50,000 (equivalent to C$62,740 in 2023), without admission of liability.[82]

British Columbia Court of Appeal

[edit]Crown appeal

[edit]On January 7, 2008, the Attorney General filed an appeal in the British Columbia Court of Appeal, against Pickton's acquittals on the first-degree murder charges.[83] The grounds of appeal related to a number of evidentiary rulings made by the trial judge, certain aspects of the trial judge's jury instructions, and the ruling to sever the six charges Pickton was tried on from the remaining twenty.[84][85][86] Although Pickton had been acquitted on the first-degree murder charges, he was convicted of second-degree murder and received the same sentence as he would have on first-degree murder convictions. The relatives of the victims expressed concern that the convictions would be jeopardized if the Crown argued that the trial judge had made errors. Opposition critic Leonard Krog criticized the Attorney-General for not having briefed the victims' families in advance.[87]

Wally Oppal apologized to the victims' families for not informing them of the appeal before it was announced to the general public.[87][88] Oppal also said that the appeal was filed largely for "strategic" reasons, in anticipation of an appeal by the defence.[89] Under the applicable rules of court,[90] the time period for the Crown to appeal expired thirty days after December 9, when the verdicts were rendered, while the time period for the defence to appeal expired thirty days after December 11, when Pickton was sentenced.[87]

Defence appeal

[edit]On January 9, 2008, lawyers for Pickton filed a notice of appeal in the British Columbia Court of Appeal, seeking a new trial on six counts of second-degree murder.[91][92][93] The notice of appeal enumerated various areas in which the defence alleged that the trial judge erred: the main charge to the jury, the response to the jurors' questions, amending the jury charge, similar fact evidence, and Pickton's statements to the police.[94]

Decisions

[edit]The British Columbia Court of Appeal issued its decisions on June 25, 2009, including some banned from publication.[95][96][97] It dismissed the defence appeal by a 2:1 majority.[98] Due to a dissent on a point of law, Pickton was entitled to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, without first seeking leave to appeal.[99] His notice of appeal was filed in the Supreme Court of Canada on August 24, 2009.[100] The Court of Appeal allowed the Crown appeal, finding that the trial judge erred in excluding some evidence and in severing six counts from the rest. The order resulting from this severance was stayed, so that the conviction on the six counts of second degree murder was not set aside.[101]

Supreme Court appeal

[edit]On June 26, 2009, Pickton's lawyers confirmed that they would exercise his right to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. The appeal was based on the dissent in the British Columbia Court of Appeal.[102] While Pickton had an automatic right to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada based on the legal issues on which Justice Donald had dissented, Pickton's lawyers applied to the Supreme Court of Canada for leave to appeal on other issues as well. On November 26, 2009, the Supreme Court of Canada granted this application for leave to appeal. The effect of this was to broaden the scope of Pickton's appeal, allowing him to raise arguments that had been rejected unanimously in the British Columbia Court of Appeal.[103][104][105] On July 30, 2010, the Supreme Court of Canada rendered its decision dismissing Pickton's appeal and affirming his convictions.[106] The argument that Pickton should be granted a new trial was unanimously rejected by the Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada.[107]

Although unanimous in its result, the Supreme Court split six to three in its legal analysis of the case. The issue was whether the trial judge made a legal error in his instructions to the jury, and in particular in his "re-instruction" responding to the jury's question about Pickton's liability if he was not the only person involved. Writing for the majority, Madam Justice Charron found that "the trial judge's response to the question posed by the jury did not adversely impact on the fairness of the trial". She further found that the trial judge's overall instructions with respect to other suspects "compendiously captured the alternative routes to liability that were realistically in issue in this trial. The jury was also correctly instructed that it could convict Mr. Pickton if the Crown proved this level of participation coupled with the requisite intent."[108] Justice Louis LeBel, writing for the minority, found that the jury was not properly informed "of the legal principles which would have allowed them as triers of fact to consider evidence of Mr. Pickton's aid and encouragement to an unknown shooter, as an alternative means of imposing liability for the murders".[109][108]

Judicial aftermath

[edit]Discontinuance of prosecution

[edit]British Columbia Crown spokesman Neil MacKenzie announced that prosecution of the 20 other murder charges would likely be discontinued: "In reaching this position, the branch has taken into account the fact that any additional convictions could not result in any increase to the sentence that Mr. Pickton has already received."[110] Families of the victims had varied reactions to this announcement. Some were disappointed that Pickton would never be convicted of the twenty other murders, while others were relieved that the gruesome details of the murders would not be aired in court.[111]

Management review of investigation

[edit]In 2010, the Vancouver Police Department issued a statement that an "exhaustive management review of the Missing Women Investigation" had been conducted, and the Vancouver Police Department would make the Review available to the public once the criminal matters are concluded and the publication bans are removed. In addition, the Vancouver Police Department disclosed that for several years it has "communicated privately to the Provincial Government that it believed a Public Inquiry would be necessary for an impartial examination of why it took so long for Robert Pickton to be arrested".[112][113] In August 2010, the publication ban imposed during Pickton's trial in 2006 was lifted.[20] The journalist Jerry Langton wrote: "The now-public details of the investigation and trial appalled many. The unwillingness of the police to pursue Pickton, despite overwhelming evidence, smacked hard of racism, sexism, and bias against drug addicts and sex workers. Many felt that the police treated crimes against aboriginals, drug addicts, sex workers and, in particular women, as less important than they should have".[20] The Pickton case seriously damaged the image of the police forces of the Lower Mainland.[20]

Apology by police department

[edit]At a press conference, Deputy Chief Constable Doug LePard of the Vancouver Police Department apologized to the victims' families: "I wish from the bottom of my heart that we would have caught him sooner. I wish that, the several agencies involved, that we could have done better in so many ways. I wish that all the mistakes that were made, we could undo. And I wish that more lives would have been saved. So on my behalf and behalf of the Vancouver Police Department and all the men and women that worked on this investigation, I would say to the families how sorry we all are for your losses and because we did not catch this monster sooner."[114]

Inquiry

[edit]After Pickton lost his final appeal at the Supreme Court of Canada, the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry chaired by Wally Oppal was called to examine the role of the Vancouver police and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in the disappearances and murders of women in the Downtown Eastside. Families of the missing and murdered women have been calling for public hearings since before Pickton was arrested and eventually convicted of six murders.[115] The commission's final report submission to the Attorney General was dated November 19, 2012, and was released to the public on December 17.[116] During the inquiry, lawyers for some of the victims' families sought to have an unpublished 289-page manuscript authored by former police investigator Lorimer Shenher entered as evidence and made entirely public. Several passages were read into the inquiry's record but Commissioner Oppal declined to publicize the entire manuscript.[117] As an extension of The Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was formed by the Government of Canada in September 2016.[118]

Transfer to penitentiary

[edit]During a court hearing on August 4, 2010, Judge Williams stated that Pickton should be committed to a federal penitentiary; up to that point he had been held at a provincial pretrial institution.[111] In June 2018, he was transferred from Kent Institution in British Columbia to Port-Cartier Institution in Quebec.[119]

Parole eligibility

[edit]In February 2024, Pickton became eligible to apply for day parole. No Parole Board of Canada hearing was scheduled.[120]

Death

[edit]On May 19, 2024, Pickton was attacked by another prisoner at the Port-Cartier Institution in Quebec. The prisoner, Martin Charest, described as having a history of assaulting other prisoners, "speared" Pickton in the head with a "broken broom-like handle". Pickton was airlifted to a hospital and put on life support.[121][122][123] He died at a hospital in Quebec City from complications of the attack on May 31.[124][10][125]

Media and merchandise

[edit]A major plotline in the Canadian crime drama Da Vinci's Inquest deals with a spate of missing women thought to be victims of a prolific serial killer hunting in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Pickton is not directly referred to by name, but starting in the show's fifth season characters and advertisements made reference to "the pig farm" in relation to the case.[126]

In August 2006, Thomas Loudamy, a 27-year-old Fremont, California, resident, claimed that he had received three letters from Pickton in response to letters Loudamy sent under an assumed identity.[127][128] Loudamy, an aspiring journalist, claimed that his motivation in releasing the letters was to help the public gain insights into Pickton.[129]

Killer Pickton is a 2005 American horror film loosely based on Pickton's killings. In 2015, a film with the working title of Full Flood began production in Vancouver by CBC-TV. Based on Stevie Cameron's book On The Farm, it was to use the life experiences of Pickton's victims for a fictional story about women in the Downtown Eastside who became victims of a serial killer.[130] Pickton was portrayed by Ben Cotton in the film. In 2016, the film was released under the title Unclaimed, and also as On the Farm in certain markets.[131]

In 2009, the Criminal Minds season 4 two-part finale, "To Hell ... And Back", based the storyline on Pickton's case. Though names and locations were changed (Pickton's character was named Mason Turner, and acts take place in Ontario instead of British Columbia), many key details were used, including two brothers living on a run-down family pig farm who would abduct sex workers and homeless women and bringing them back to the farm before feeding the remains to the pigs.[132]

In 2011, Vancouver artist Pamela Masik planned to mount an art exhibition, The Forgotten, featuring portraits of some of Pickton's victims, at the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology, which declined to host it after some controversy.[133] The incident was profiled by Damon Vignale in the 2013 documentary film The Exhibition.[134]

In 2011, a documentary was released, titled The Pig Farm, which outlined the flawed investigative work by the RCMP and the Vancouver Police Service. Details emerged about the impossibly long list of suspects, departmental in-fighting and lack of resources.

In 2016, a purported autobiography, Pickton: In his Own Words, was released. Its publication and marketing initiated controversy, critical petitions, and government action to stop him from profiting from the work.[135][136] Pig Killer, a biopic written and directed by Chad Ferrin, starring Jake Busey as Pickton, was released in select theatres on November 17, 2023.

In 2024, the comedy troupe Danger Cats was selling T-shirts online with a caricature of Pickton headlined with "Pickton Farms". Under the caricature was the tagline "Over 50 flavors of hookery smoked bacon". The shirt caused controversy. The British Columbia premier David Eby expressed his outrage: "All I can say is how deeply disappointed I am by the idea that the lives of vulnerable women could be trivialized like this." Upcoming shows of Danger Cats were cancelled and the shirt was removed from their online store.[137]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Butts, Edward (October 8, 2020). "Robert Pickton Case". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

While Pickton was being held in jail in Surrey, British Columbia, he shared a cell with an undercover RCMP officer he believed to be another detainee.

- ^ "Crown says Pickton confessed to killing 49". CTVNews. January 22, 2007. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

- ^ "Pickton butchered 6 women, Crown tells jury". CBC. January 22, 2007. Archived from the original on September 17, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ "Indictment document". Archived from the original on October 7, 2006.

- ^ "AU Serial-killing pig farmer gets life". "ABC. December 12, 2007. Archived from the original on February 23, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Skelton, Chad (August 4, 2010). "Pickton won't face remaining 20 murder charges". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ Cui, Leigh-Anne (August 13, 2021). "View of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in the Case of Canadian Serial Killer Robert Pickton". Voices of Forensic Science. 1 (2): 29–37. Archived from the original on December 24, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ Inquiry, British Columbia. Missing Women Commission of (2012). Forsaken. Missing Women Commission of Inquiry. ISBN 978-0-9917299-7-5.

- ^ Judd, Amy (May 31, 2024). "Serial killer Robert Pickton dead following beating in Quebec prison". Global News. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ a b Brockman, Charles (May 31, 2024). "B.C. serial killer Robert Pickton dead after prison attack". CityNews Vancouver. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "Crown Says Will Prove Robert Pickton Murdered, Butchered and Disposed of 6 Women". Canadian Press. January 22, 2007. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ "Pickton's mother was a key influence". Toronto Star. June 17, 2007. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Serial Killer Who Fed His Victims to his Pigs". Medium.com. December 18, 2020. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Pickton's personality emerging as trial goes on". ctvnews.com. February 10, 2007. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ "Young Willie Pickton was shattered by the slaughter of his pet". vancouversun.com. August 9, 2010. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ "The life of Robert Pickton". theglobeandmail.com. December 10, 2007. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Piggy Palace". Crime Library. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Langton 2013, p. 220.

- ^ Langton 2013, p. 220-221.

- ^ a b c d Langton 2013, p. 221.

- ^ "Limbo". Crime Library. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Abyss". Crime Library. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Body Farm". Crime Library. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Worst Canadian Serial Killer". Crime Library. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Pickton Chronology". University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Pickton farm should be memorial: supporters of missing women". CBC News. November 22, 2008. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Chua, Steven (December 17, 2012). "Pickton farm nearly forgotten as new development emerges". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Google Maps Street View". Google Maps. April 2023. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ "'Human meat' alert at pig farm" Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Alert issued about meat from Pickton's pig farm" Archived March 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Globe and Mail. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ "Human remains from Pickton farm may have reached food supply" Archived March 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Globe and Mail. Retrieved May 16, 2015

- ^ "Canadian pig farmer guilty of serial killings" Archived July 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. The Australian, Obtained on July 31, 2018.

- ^ Culbert, Lori (August 4, 2010). "Pickton murders: Bloody knife fight left one victim barely alive; the victim later on died". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ Wendy Stueck, "Former Vancouver detective pens memoir on Robert Pickton case" Archived May 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The Globe and Mail, September 4, 2015

- ^ Jolly, Joanna (June 1, 2017). "Why I failed to catch Canada's worst serial killer". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "Pickton trial to start Monday". CBC. January 30, 2006. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- ^ "1 of 27 murder charges against Pickton thrown out". CBC. March 2, 2006. Archived from the original on February 12, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2006.

- ^ "Pickton to be initially tried on six counts of murder". CBC. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

Geoffrey Gaul, a spokesman for the Crown, said his office will have to consider its next move. "Which should go first? Should we go to trial with those six counts or should we look at the other 20 and should we proceed on those 20 or should we proceed on a number of those 20? Those are discretionary calls that the prosecution will make."

- ^ "Robert Pickton found guilty of six counts of second degree murder". December 9, 2007. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007.

- ^ "2nd Pickton trial may not go ahead, families told". February 26, 2008. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ "Pickton to be initially tried on 6 counts of murder". CBC. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original on February 12, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2006.

- ^ "Two trials for Canada pig farmer". BBC News. September 9, 2006. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ^ "Pickton trial to be delayed two weeks". CanWest Interactive. December 18, 2006. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- ^ Jones, Deborah (January 26, 2007). "The Case of the Serial Killer". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Deborah (January 24, 2007). "Court hears of Canadian pig farmer's claim to 49 murders". Melbourne: theage.com.au. Archived from the original on January 25, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ "Prosecutors: Pig farmer confessed to 49 killings". CNN. January 22, 2007. Archived from the original on January 24, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Judge suspends Pickton jury deliberations". Cbc.ca. December 7, 2007. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- ^ Fong, Petti (December 7, 2007). "Error shakes Pickton trial | Toronto Star". Star. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Culbert, Lori (August 4, 2010). "Juror hauled before the judge partway through Pickton trial". Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ Mickleburgh, Rod; Matas, Robert (December 9, 2007). "Pickton guilty on 6 counts of second-degree murder". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ "Pickton gets maximum sentence for murders". CBC. December 12, 2007. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ Fournier, Suzanne; Fraser, Keith; Jiwa, Salim (February 26, 2002). "Daughter phoned daily for 13 years". The Province. Archived from the original on June 23, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ Fong, Petti; Kines, Lindsay (February 26, 2002). "Sister trapped by drugs, prostitution". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ "Brenda Ann Wolfe-last seen Feb 1999". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Daughter phoned daily for 13 years". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on June 23, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Friscolanti, Michael (April 3, 2002). "'Bright young woman' among victims". National Post. Archived from the original on April 11, 2002. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ "Bringng home Dianne's life-Apr 5, 2002". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on June 12, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Crown adds three more murder charges against pig farmer-Apr 2, 2002". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on April 11, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Helen Mae Hallmark". Missingpeople.net. January 1, 2007. Archived from the original on June 17, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Patricia Rose Johnson". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on September 1, 2003. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Pickton charged with four more murders in B.C. missing women case". cbc.ca. Archived from the original on February 1, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2002.

- ^ "Alleged Pickton victim schooled in Comox Valley-Oct 2002". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on December 8, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Inga Monique Hall". Missingpeople.net. January 1, 2007. Archived from the original on April 10, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Missing woman's DNA located, Police say Sarah deVries identified-Aug 8, 2002". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on December 8, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Pictures provide the clues to a daughter's lost life". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on September 14, 2006. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Angela Rebecca Jardine". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on June 17, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Lupick, Travis (2017). Fighting For Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City's Struggle With Addiction. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1-55152-712-3. OCLC 1005092569.

- ^ "Diana Melnick". Missingpeople.net. January 1, 2007. Archived from the original on June 17, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Debra Lynne Jones-last seen Dec 21, 2000". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on October 20, 2001. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Andrea Fay Borhaven". Missingpeople.net. January 1, 2007. Archived from the original on April 10, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Cara Louise Ellis last seen in 1997". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on October 11, 2004. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Task force adds four missing women-Nov 20, 2003". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on January 16, 2004. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "RCMP: Pickton suspect in death of Victoria woman". Canadian Press. October 12, 2006. Archived from the original on October 21, 2006.

- ^ "Yvonne Marie Boen-Mar 28, 2002". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on January 1, 2003. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Pickton farm yields 23rd woman's DNA-Jan 16, 2004". Missingpeople.net. Archived from the original on January 18, 2004. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ de Vos, Gail (January 11, 2008). "Finding Dawn". Canadian Materials. XIV (10). Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ Welsh, Christine (2006). "Finding Dawn". Documentary film. National Film Board of Canada. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ MacQueen, Ken (August 13, 2010). "How serial killer Robert Pickton slipped away". Macleans.ca. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ King, Gary. (2009). Butcher. New York: Kensington Publishing.

- ^ "Robert Pickton Inquiry". Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ "Children of alleged Pickton victims launch civil lawsuit". CBC News. May 9, 2013. Archived from the original on December 14, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "'Strong, solid' settlement sees thirteen of serial killer Robert Pickton's victims' children get $50,000 each". National Post. March 17, 2014. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ "Crown seeks new trial for Pickton". CBC. January 7, 2008. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "Crown appeals Pickton's convictions". The Toronto Star. January 7, 2008. Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- ^ "Notice of Appeal (Crown Appeal Against Acquittal)" (PDF). CBC News. January 7, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Matas, Robert (January 4, 2008). "Defence appeal in Pickton case a 'no-brainer'". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c Culbert, Lori (January 7, 2008). "Crown happy with Pickton verdict, despite appeal". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "Oppal apologizes". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Canadian Press. January 8, 2008. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Dowd, Allan (January 7, 2008). "Surprise appeal in Canadian serial killer case". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "British Columbia Court of Appeal Criminal Appeal Rules, 1986, B.C. Reg. 145/86". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Culbert, Lori (January 9, 2008). "Pickton's lawyers file appeal, allege errors in 6 areas". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "Pickton's lawyers launch appeal". CBC. January 9, 2008. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Hall, Neal (January 8, 2008). "Former prosecutor to file Pickton defence appeal". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "Notice of Appeal" (PDF). CBC News. January 9, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "Publication Bans R v. Pickton" (PDF). The Courts of British Columbia. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 9, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Provincial Court Publication Bans: R. v. Pickton" (PDF). Supreme Court of Canada. January 15, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 9, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "Court of Appeal – Recently Posted Judgments". Courts.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Best, Cris (August 6, 2010). "R. v. Pickton (2010): The SCC Disagrees on the Correct Path to the Same Conclusion – TheCourt.ca". The Court. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Paragraph 691(1)(a) of the Criminal Code Archived June 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ SCC Docket number 33288 Archived June 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ R. v. Pickton, 2009 BCCA 300

- ^ "Pickton to appeal convictions to Supreme Court of Canada". CBC. June 26, 2006. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2006.

- ^ Tibbetts, Janice (November 26, 2009). "Robert Pickton's lawyers win bid to broaden scope of serial killer's appeal". Vancouver Sun. Canwest News Service. Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ "Supreme Court of Canada press release". November 26, 2009. Archived from the original on December 4, 2009.

- ^ "Supreme Court of Canada case information – docket 33288". Archived from the original on June 14, 2011.

- ^ "Judgments in Appeals" (Press release). Supreme Court of Canada. July 30, 2010. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Serial killer Robert Pickton's appeal denied". Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b R. v. Pickton Archived October 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, 2010 SCC 32

- ^ "Subparagraph 686(1)(b)(iii) of the Criminal Code". Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Robert Pickton won't get new trial: top court". CBC. July 30, 2010. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Mickleburgh, Rod (August 4, 2010). "Pickton legal saga ends as remaining charges stayed". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "VPD Statement — Supreme Court Ruling on Pickton Case" (PDF) (Press release). Vancouver Police Department. July 30, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Supplemental information provided to the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women" (PDF). December 13, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ "Vancouver deputy police chief Doug LePard's personal, unscripted comments about the investigation into serial killer Robert Pickton". CBC News. July 30, 2010. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Public inquiry into Pickton murders to begin Tuesday". CTV News. October 10, 2011. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Missing Women Commission of Inquiry". Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Hutchinson, Brian (May 25, 2012). "Deadly Dysfunction: Scathing undisclosed details from inside the Pickton investigation". National Post. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ "Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1b" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ "Robert Pickton transferred to Quebec prison, according to victim's family". CBC News. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ MacMahon, Martin (February 22, 2024). "Victims' families hold vigil as Robert Pickton becomes eligible to apply for day parole". CTV News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Bolan. "B.C. serial killer Robert Pickton savagely attacked in prison, clinging to life". The Province. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Serial killer Robert Pickton in critical condition after prison assault". CBC. May 21, 2024. Archived from the original on May 21, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Séguin, Félix (May 22, 2024). Le tueur en série Robert Pickton aurait été agressé par un dangereux récidiviste. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024 – via www.journaldemontreal.com.

- ^ Judd, Amy (May 31, 2024). "Serial killer Robert Pickton dead following beating in Quebec prison". Global News. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ ICI.Radio-Canada.ca, Zone Justice et faits divers- (May 31, 2024). "Le tueur en série Robert Pickton est mort". Radio-Canada (in Canadian French). Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ "Reflexive Hybrid Realism in Da Vinci's Inquest". Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Exclusive Pickton letters". Canada.com. December 10, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ "The Pickton Letters: In his own words". Canada.com. December 10, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ "Sun Exclusive: The Pickton Letters". Vancouver Sun. September 2, 2006. Archived from the original on October 7, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ "Robert Pickton case: Movie on victims starts filming in Vancouver next week". CBC News – Arts & Entertainment. February 27, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ "On the Farm: A story of survival". Archived from the original on April 30, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ Jeunesse, Marilyn La. "11 episodes of 'Criminal Minds' that were likely inspired by real-life crimes". Business Insider. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Lori Culbert, "UBC cancels portrait exhibit of Downtown Eastside's vanished women". Vancouver Sun, January 13, 2011.

- ^ Julianna Cummins, "The Exhibition wins CSA's 2015 Diversity Award" Archived December 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Playback, February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Robert Pickton book 'deeply disturbing': B.C. solicitor general". CTV News. February 22, 2016. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ Stueck, Wendy (February 22, 2016). "Robert Pickton book pulled from production after public outcry". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Comedy show in B.C. cancelled after outrage over troupe's Robert Pickton T-shirts". CBC.ca. February 28, 2024. Archived from the original on February 28, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Cameron, Stevie (May 30, 2007). The Pickton File. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-676-97953-4.

- Cameron, Stevie (October 25, 2011). On the Farm: Robert William Pickton and the Tragic Story of Vancouver's Missing Women. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-676-97585-7.

- Langton, Jerry (2013). The Notorious Bacon Brothers Inside Gang Warfare on Vancouver Streets. Toronto: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9781118404577.

External links

[edit]- Women Commission of Inquiry ("Oppal") Report (November 19, 2012)

- R. v. Pickton, Full text of Supreme Court of Canada decision available at LexUM and CanLII (July 30, 2010)

- R. v. Pickton, decision of the Court of Appeal for British Columbia (June 25, 2009) (defence appeal)

- R. v. Pickton, decision of the Court of Appeal for British Columbia (June 25, 2009) (Crown appeal)

- R. v. Pickton, decision of the Supreme Court of British Columbia (December 13, 2007) (ruling re: re-instructing the jury)

- R. v. Pickton, decision of the Supreme Court of British Columbia (January 16, 2007) (ruling re: media application to access and publish exhibits #1)

- Robert William Pickton Trial Information (Court Services, Ministry of Attorney General)

- Covering The Trial: Former Sex Trade Workers Work As Citizen Correspondents For Orato

- Backgrounder

- TruTV article on Robert Pickton

- Vancouver Eastside Missing Women[usurped]

- BBC Article on Pickton (2007-01-21)

- Excerpts from 'The Pickton letters'[usurped]

- Pat Casanova testimony, June 4–6, 2007

- History of Sex Work in Vancouver Archived December 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (downloadable PDF book written by sex workers)

- PDFs of the Pickton letters obtained by The Vancouver Sun

- Interviews and oral histories with victims' families and community workers, part of research stored at Simon Fraser University Library.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch