COVID-19 vaccine

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: This article is not following summary style and buries information on the latest vaccines. (September 2024) |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Vaccine type | mRNA, viral, inactivated, protein |

| Clinical data | |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

| |

A COVID‑19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19).

Before the COVID‑19 pandemic, an established body of knowledge existed about the structure and function of coronaviruses causing diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). This knowledge accelerated the development of various vaccine platforms in early 2020.[1] The initial focus of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines was on preventing symptomatic, often severe, illness.[2] In 2020, the first COVID‑19 vaccines were developed and made available to the public through emergency authorizations[3] and conditional approvals.[4][5] Initially, most COVID‑19 vaccines were two-dose vaccines, with the exception single-dose vaccines Convidecia[6] and the Janssen COVID‑19 vaccine,[3] and vaccines with three-dose schedules, Razi Cov Pars[7] and Soberana.[8] However, immunity from the vaccines has been found to wane over time, requiring people to get booster doses of the vaccine to maintain protection against COVID‑19.[3]

The COVID‑19 vaccines are widely credited for their role in reducing the spread of COVID‑19 and reducing the severity and death caused by COVID‑19.[3][9] According to a June 2022 study, COVID‑19 vaccines prevented an additional 14.4 to 19.8 million deaths in 185 countries and territories from 8 December 2020 to 8 December 2021.[10] Many countries implemented phased distribution plans that prioritized those at highest risk of complications, such as the elderly, and those at high risk of exposure and transmission, such as healthcare workers.[11][12]

Common side effects of COVID‑19 vaccines include soreness, redness, rash, inflammation at the injection site, fatigue, headache, myalgia (muscle pain), and arthralgia (joint pain), which resolve without medical treatment within a few days.[13][14] COVID‑19 vaccination is safe for people who are pregnant or are breastfeeding.[15]

As of 12 August 2024[update], 13.72 billion doses of COVID‑19 vaccines have been administered worldwide, based on official reports from national public health agencies.[16] By December 2020, more than 10 billion vaccine doses had been preordered by countries,[17] with about half of the doses purchased by high-income countries comprising 14% of the world's population.[18]

Despite the extremely rapid development of effective mRNA and viral vector vaccines, worldwide vaccine equity has not been achieved. The development and use of whole inactivated virus (WIV) and protein-based vaccines have also been recommended, especially for use in developing countries.[19][20]

The 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman for the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19.[21][22][23]

Background

- COVID‑19 vaccine doses administered by continent as of October 11, 2021. For vaccines that require multiple doses, each individual dose is counted. As the same person may receive more than one dose, the number of doses can be higher than the number of people in the population.

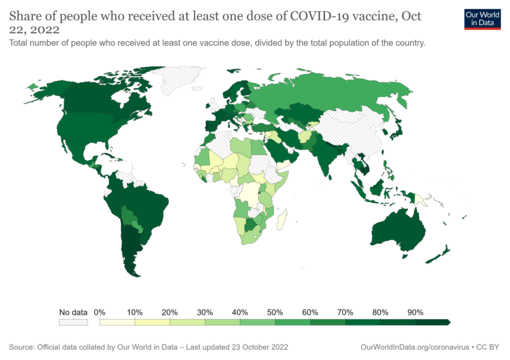

- Map showing share of population fully vaccinated against COVID-19 relative to a country's total population[note 1]

Prior to COVID‑19, a vaccine for an infectious disease had never been produced in less than several years – and no vaccine existed for preventing a coronavirus infection in humans.[24] However, vaccines have been produced against several animal diseases caused by coronaviruses, including (as of 2003) infectious bronchitis virus in birds, canine coronavirus, and feline coronavirus.[25] Previous projects to develop vaccines for viruses in the family Coronaviridae that affect humans have been aimed at severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Vaccines against SARS[26] and MERS[27] have been tested in non-human animals.

According to studies published in 2005 and 2006, the identification and development of novel vaccines and medicines to treat SARS was a priority for governments and public health agencies around the world at that time.[28][29][30] There is no cure or protective vaccine proven to be safe and effective against SARS in humans.[31][32] There is also no proven vaccine against MERS.[33] When MERS became prevalent, it was believed that existing SARS research might provide a useful template for developing vaccines and therapeutics against a MERS-CoV infection.[31][34] As of March 2020, there was one (DNA-based) MERS vaccine that completed Phase I clinical trials in humans,[35] and three others in progress, all being viral-vectored vaccines: two adenoviral-vectored (ChAdOx1-MERS, BVRS-GamVac) and one MVA-vectored (MVA-MERS-S).[36]

Vaccines that use an inactive or weakened virus that has been grown in eggs typically take more than a decade to develop.[37][38] In contrast, mRNA is a molecule that can be made quickly, and research on mRNA to fight diseases was begun decades before the COVID‑19 pandemic by scientists such as Drew Weissman and Katalin Karikó, who tested on mice. Moderna began human testing of an mRNA vaccine in 2015.[37] Viral vector vaccines were also developed for the COVID‑19 pandemic after the technology was previously cleared for Ebola.[37]

As multiple COVID‑19 vaccines have been authorized or licensed for use, real-world vaccine effectiveness (RWE) is being assessed using case control and observational studies.[39][40] A study is investigating the long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 provided by the mRNA vaccines.[41][42]

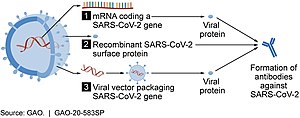

Vaccine technologies

As of July 2021, at least nine different technology platforms were under research and development to create an effective vaccine against COVID‑19.[44][45] Most of the platforms of vaccine candidates in clinical trials are focused on the coronavirus spike protein (S protein) and its variants as the primary antigen of COVID‑19 infection,[44] since the S protein triggers strong B-cell and T-cell immune responses.[46][47] However, other coronavirus proteins are also being investigated for vaccine development, like the nucleocapsid, because they also induce a robust T-cell response and their genes are more conserved and recombine less frequently (compared to Spike).[47][48][49] Future generations of COVID‑19 vaccines that may target more conserved genomic regions will also act as insurance against the manifestation of catastrophic scenarios concerning the future evolutionary path of SARS-CoV-2, or any similar coronavirus epidemic/pandemic.[50]

Platforms developed in 2020 involved nucleic acid technologies (nucleoside-modified messenger RNA and DNA), non-replicating viral vectors, peptides, recombinant proteins, live attenuated viruses, and inactivated viruses.[24][44][51][52]

Many vaccine technologies being developed for COVID‑19 are not like influenza vaccines but rather use "next-generation" strategies for precise targeting of COVID‑19 infection mechanisms.[44][51][52] Several of the synthetic vaccines use a 2P mutation to lock the spike protein into its prefusion configuration, stimulating an adaptive immune response to the virus before it attaches to a human cell.[53] Vaccine platforms in development may improve flexibility for antigen manipulation and effectiveness for targeting mechanisms of COVID‑19 infection in susceptible population subgroups, such as healthcare workers, the elderly, children, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.[44][51]

mRNA vaccines

Several COVID‑19 vaccines, such as the Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, use RNA to stimulate an immune response. When introduced into human tissue, the vaccine contains either self-replicating RNA or messenger RNA (mRNA), which both cause cells to express the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. This teaches the body how to identify and destroy the corresponding pathogen. RNA vaccines often use nucleoside-modified messenger RNA. The delivery of mRNA is achieved by a coformulation of the molecule into lipid nanoparticles, which protect the RNA strands and help their absorption into the cells.[54][55][56][57]

RNA vaccines are the first COVID‑19 vaccines to be authorized in the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union.[58][59] Authorized vaccines of this type include the Pfizer–BioNTech

Severe allergic reactions are rare. In December 2020, 1,893,360 first doses of Pfizer–BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine administration resulted in 175 cases of severe allergic reactions, of which 21 were anaphylaxis.[66] For 4,041,396 Moderna COVID‑19 vaccine dose administrations in December 2020 and January 2021, only ten cases of anaphylaxis were reported.[66] Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) were most likely responsible for the allergic reactions.[66]

Adenovirus vector vaccines

These vaccines are examples of non-replicating viral vector vaccines using an adenovirus shell containing DNA that encodes a SARS‑CoV‑2 protein.[67][68] The viral vector-based vaccines against COVID‑19 are non-replicating, meaning that they do not make new virus particles but rather produce only the antigen that elicits a systemic immune response.[67]

Authorized vaccines of this type include the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‑19 vaccine,

Convidecia and Janssen are both one-shot vaccines that offer less complicated logistics and can be stored under ordinary refrigeration for several months.[75][76]

Sputnik V uses Ad26 for its first dose, which is the same as Janssen's only dose, and Ad5 for the second dose, which is the same as Convidecia's only dose.[77]

In August 2021, the developers of Sputnik V proposed, in view of the Delta case surge, that Pfizer test the Ad26 component (termed its 'Light' version)[78] as a booster shot.[79]

Inactivated virus vaccines

Inactivated vaccines consist of virus particles that are grown in culture and then killed using a method such as heat or formaldehyde to lose disease-producing capacity while still stimulating an immune response.[80]

Inactivated virus vaccines authorized in China include the Chinese CoronaVac[81][82][83] and the Sinopharm BIBP

Subunit vaccines

Subunit vaccines present one or more antigens without introducing whole pathogen particles. The antigens involved are often protein subunits, but they can be any molecule fragment of the pathogen.[90]

The authorized vaccines of this type include the peptide vaccine EpiVacCorona,

The V451 vaccine was in clinical trials that were terminated after it was found that the vaccine may potentially cause incorrect results for subsequent HIV testing.

Virus-like particle vaccines

The authorized vaccines of this type include the Novavax COVID‑19 vaccine.[19][104]

Other types

Additional types of vaccines that are in clinical trials include multiple DNA plasmid vaccines,[105]

Scientists investigated whether existing vaccines for unrelated conditions could prime the immune system and lessen the severity of COVID‑19 infections.[114] There is experimental evidence that the BCG vaccine for tuberculosis has non-specific effects on the immune system, but there is no evidence that this vaccine is effective against COVID‑19.[115]

List of authorized vaccines

| Common name | Type (technology) | Country of origin | First authorization | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authorized in more than 10 countries and by the WHO | ||||

| Oxford–AstraZeneca | Adenovirus vector | United Kingdom, Sweden | December 2020 | |

| Pfizer–BioNTech | RNA | Germany, United States | December 2020 | Both original and Omicron variant versions |

| Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) | Adenovirus vector | United States, Netherlands | February 2021 | |

| Moderna | RNA | United States | December 2020 | Both original and Omicron variant versions |

| Sinopharm BIBP | Inactivated | China | July 2020 | |

| Novavax | Subunit/virus-like particle | United States | December 2021 | A "recombinant nanoparticle vaccine"[116] |

| Covaxin | Inactivated | India | January 2021 | |

| CoronaVac | Inactivated | China | August 2020 | Low efficacy in replication studies and with certain variants |

| Sanofi–GSK | Subunit | France, United Kingdom | November 2022 | Based on Beta variant |

| Authorized in more than 10 countries | ||||

| Sputnik V | Adenovirus vector | Russia | August 2020 | |

| Valneva | Inactivated | France, Austria | April 2022 | |

| Sputnik Light | Adenovirus vector | Russia | May 2021 | |

| Authorized in 2–10 countries | ||||

| Convidecia | Adenovirus vector | China | June 2020 | |

| Sinopharm WIBP | Inactivated | China | February 2021 | Lower efficacy |

| Abdala | Subunit | Cuba | July 2021 | |

| EpiVacCorona | Subunit | Russia | October 2020 | |

| Zifivax | Subunit | China | March 2021 | |

| Soberana 02 | Subunit | Cuba, Iran | June 2021 | |

| CoviVac | Inactivated | Russia | February 2021 | |

| Medigen | Subunit | Taiwan | July 2021 | |

| QazCovid-in | Inactivated | Kazakhstan | April 2021 | |

| Minhai | Inactivated | China | May 2021 | Undergoing clinical trials |

| COVIran Barekat | Inactivated | Iran | June 2021 | |

| Soberana Plus | Subunit | Cuba | August 2021 | |

| Corbevax | Subunit | India, United States | December 2021 | |

| Authorized in 1 country | ||||

| Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences | Inactivated | China | June 2021 | |

| ZyCoV-D | DNA | India | August 2021 | |

| FAKHRAVAC | Inactivated | Iran | September 2021 | |

| COVAX-19 | Subunit | Australia, Iran | October 2021 | |

| Razi Cov Pars | Subunit | Iran | October 2021 | |

| Turkovac | Inactivated | Turkey | December 2021 | |

| Sinopharm CNBG | Subunit | China | December 2021 | Based on original, Beta, and Kappa variants |

| CoVLP | Virus-like particle | Canada, United Kingdom | February 2022 | |

| Noora | Subunit | Iran | March 2022 | |

| Skycovione | Subunit | South Korea | June 2022 | |

| Walvax | RNA | China | September 2022 | Granted emergency use approval in Indonesia in September 2022 |

| iNCOVACC | Adenovirus vector | India | September 2022 | Nasal vaccine |

| V-01 | Subunit | China | September 2022 | |

| Gemcovac | RNA | India | October 2022 | Self-amplifying RNA vaccine |

| IndoVac | Subunit | Indonesia | October 2022 | |

| LUNAR-COV19 | RNA | USA, Singapore | November 2023 | Self-amplifying RNA vaccine |

| Kostaive | RNA | Japan | November 2023 | Self-amplifying RNA vaccine |

Delivery methods

Most coronavirus vaccines are administered by injection, with further vaccine delivery methods being studied for future coronavirus vaccines.

Intranasal

Intranasal vaccines target mucosal immunity in the nasal mucosa, which is a portal for viral entry into the body.[117][118] These vaccines are designed to stimulate nasal immune factors, such as IgA.[117] In addition to inhibiting the virus, nasal vaccines provide ease of administration because no needles (or needle phobia) are involved.[118][119]

A variety of intranasal COVID‑19 vaccines are undergoing clinical trials. The first authorised intranasal vaccine was Razi Cov Pars in Iran at the end of October 2021.[120] The first viral component of Sputnik V vaccine was authorised in Russia as Sputnik Nasal in April 2022.[121] In September 2022, India and China approved two nasal COVID‑19 vaccines (iNCOVACC and Convidecia), which may (as boosters)[122] also reduce transmission[123][124] (potentially via sterilizing immunity).[123] In December 2022, China approved a second intranasal vaccine as a booster, trade name Pneucolin.[125]

Autologous

Aivita Biomedical is developing an experimental autologous dendritic cell COVID‑19 vaccine kit where the vaccine is prepared and incubated at the point-of-care using cells from the intended recipient.[126] The vaccine is undergoing small phase I and phase II clinical studies.[126][127][128]

Universal vaccine

A universal coronavirus vaccine would be effective against all coronaviruses and possibly other viruses.[129][130] The concept was publicly endorsed by NIAID director Anthony Fauci, virologist Jeffery K. Taubenberger, and David M. Morens.[131] In March 2022, the White House released the "National COVID‑19 Preparedness Plan", which recommended accelerating the development of a universal coronavirus vaccine.[132]

One attempt at such a vaccine is being developed at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. It uses a spike ferritin-based nanoparticle (SpFN). This vaccine began a Phase I clinical trial in April 2022.[133] Results of this trial were published in May 2024.[134] Other universal vaccines that have entered clinical trial include OVX033 (France),[135] PanCov (France),[136] pEVAC-PS (UK),[137] and VBI-2902 (Canada).[138]

Another strategy is to attach vaccine fragments from multiple strains to a nanoparticle scaffold. One theory is that a broader range of strains can be vaccinated against by targeting the receptor-binding domain, rather than the whole spike protein.[139]

Formulation

As of September 2020[update], eleven of the vaccine candidates in clinical development use adjuvants to enhance immunogenicity.[44] An immunological adjuvant is a substance formulated with a vaccine to elevate the immune response to an antigen, such as the COVID‑19 virus or influenza virus.[140] Specifically, an adjuvant may be used in formulating a COVID‑19 vaccine candidate to boost its immunogenicity and efficacy to reduce or prevent COVID‑19 infection in vaccinated individuals.[140][141] Adjuvants used in COVID‑19 vaccine formulation may be particularly effective for technologies using the inactivated COVID‑19 virus and recombinant protein-based or vector-based vaccines.[141] Aluminum salts, known as "alum", were the first adjuvant used for licensed vaccines and are the adjuvant of choice in some 80% of adjuvanted vaccines.[141] The alum adjuvant initiates diverse molecular and cellular mechanisms to enhance immunogenicity, including the release of proinflammatory cytokines.[140][141]

In June 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advised the manufacturers of the licensed and authorized COVID-19 vaccines that the COVID-19 vaccines (2024-2025 Formula) for use in the United States beginning in fall 2024 should be monovalent JN.1 vaccines.[142]

Planning and development

Since January 2020, vaccine development has been expedited via unprecedented collaboration in the multinational pharmaceutical industry and between governments.[44]

Multiple steps along the entire development path are evaluated, including:[24][143]

- the level of acceptable toxicity of the vaccine (its safety),

- targeting vulnerable populations,

- the need for vaccine efficacy breakthroughs,

- the duration of vaccination protection,

- special delivery systems (such as oral or nasal, rather than by injection),

- dose regimen,

- stability and storage characteristics,

- emergency use authorization before formal licensing,

- optimal manufacturing for scaling to billions of doses, and

- dissemination of the licensed vaccine.

Challenges

There have been several unique challenges with COVID‑19 vaccine development.

Public health programs[who?] have been described as "[a] race to vaccinate individuals" with the early wave vaccines.[144]

Timelines for conducting clinical research – normally a sequential process requiring years – are being compressed into safety, efficacy, and dosing trials running simultaneously over months, potentially compromising safety assurance.[145][146] For example, Chinese vaccine developers and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention began their efforts in January 2020,[147] and by March they were pursuing numerous candidates on short timelines.[145][148]

The rapid development and urgency of producing a vaccine for the COVID‑19 pandemic were expected to increase the risks and failure rate of delivering a safe, effective vaccine.[51][52][149] Additionally, research at universities is obstructed by physical distancing and the closing of laboratories.[150][151]

Vaccines must progress through several phases of clinical trials to test for safety, immunogenicity, effectiveness, dose levels, and adverse effects of the candidate vaccine.[152][153] Vaccine developers have to invest resources internationally to find enough participants for Phase II–III clinical trials when the virus has proved to be a "moving target" of changing transmission rates across and within countries, forcing companies to compete for trial participants.[154]

Clinical trial organizers may also encounter people unwilling to be vaccinated due to vaccine hesitancy[155] or disbelief in the science of the vaccine technology and its ability to prevent infection.[156] As new vaccines are developed during the COVID‑19 pandemic, licensure of COVID‑19 vaccine candidates[who?] requires submission of a full dossier of information on development and manufacturing quality.[157][158][159]

Organizations

Internationally, the Access to COVID‑19 Tools Accelerator is a G20 and World Health Organization (WHO) initiative announced in April 2020.[160][161] It is a cross-discipline support structure to enable partners to share resources and knowledge. It comprises four pillars, each managed by two to three collaborating partners: Vaccines (also called "COVAX"), Diagnostics, Therapeutics, and Health Systems Connector.[162] The WHO's April 2020 "R&D Blueprint (for the) novel Coronavirus" documented a "large, international, multi-site, individually randomized controlled clinical trial" to allow "the concurrent evaluation of the benefits and risks of each promising candidate vaccine within 3–6 months of it being made available for the trial." The WHO vaccine coalition will prioritize which vaccines should go into Phase II and III clinical trials and determine harmonized Phase III protocols for all vaccines achieving the pivotal trial stage.[163]

National governments have also been involved in vaccine development. Canada announced funding for 96 projects for the development and production of vaccines at Canadian companies and universities, with plans to establish a "vaccine bank" that could be used if another coronavirus outbreak occurs,[164] support clinical trials, and develop manufacturing and supply chains for vaccines.[165]

China provided low-rate loans to one vaccine developer through its central bank and "quickly made land available for the company" to build production plants.[146] Three Chinese vaccine companies and research institutes are supported by the government for financing research, conducting clinical trials, and manufacturing.[166]

The United Kingdom government formed a COVID‑19 vaccine task force in April 2020 to stimulate local efforts for accelerated development of a vaccine through collaborations between industries, universities, and government agencies. The UK's Vaccine Taskforce contributed to every phase of development, from research to manufacturing.[167]

In the United States, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), a federal agency funding disease-fighting technology, announced investments to support American COVID‑19 vaccine development and the manufacturing of the most promising candidates.[146][168] In May 2020, the government announced funding for a fast-track program called Operation Warp Speed.[169][170] By March 2021, BARDA had funded an estimated $19.3 billion in COVID‑19 vaccine development.[171]

Large pharmaceutical companies with experience in making vaccines at scale, including Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), formed alliances with biotechnology companies, governments, and universities to accelerate progress toward effective vaccines.[146][145]

Clinical research

COVID-19 vaccine clinical research uses clinical research to establish the characteristics of COVID-19 vaccines. These characteristics include efficacy, effectiveness, and safety. As of November 2022[update], 40 vaccines are authorized by at least one national regulatory authority for public use:[172][173]

As of June 2022[update], 353 vaccine candidates are in various stages of development, with 135 in clinical research, including 38 in phase I trials, 32 in phase I–II trials, 39 in phase III trials, and 9 in phase IV development.[172]Post-vaccination complications

Post-vaccination embolic and thrombotic events, termed vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT),[174][175][176][177][178] vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT),[179] thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS),[180][177][178] vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT),[178] or vaccine-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VATT),[178] are rare types of blood clotting syndromes that were initially observed in a number of people who had previously received the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‑19 vaccine (AZD1222)[a] during the COVID‑19 pandemic.[179][185] It was subsequently also described in the Janssen COVID‑19 vaccine (Johnson & Johnson), leading to the suspension of its use until its safety had been reassessed.[186] On 5 May 2022 the FDA posted a bulletin limiting the use of the Janssen Vaccine to very specific cases due to further reassessment of the risks of TTS, although the FDA also stated in the same bulletin that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risks.[187]

In April 2021, AstraZeneca and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) updated their information for healthcare professionals about AZD1222, saying it is "considered plausible" that there is a causal relationship between the vaccination and the occurrence of thrombosis in combination with thrombocytopenia and that, "although such adverse reactions are very rare, they exceeded what would be expected in the general population".[185][188][189][190] AstraZeneca initially denied the link, saying "we do not accept that TTS is caused by the vaccine at a generic level". However, in legal documents filed in February 2024, AstraZeneca finally admitted its vaccine 'can, in very rare cases, cause TTS'.[191][192]History

SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus that causes COVID-19, was isolated in late 2019.[193] Its genetic sequence was published on 11 January 2020, triggering an urgent international response to prepare for an outbreak and hasten the development of a preventive COVID-19 vaccine.[194][195][196] Since 2020, vaccine development has been expedited via unprecedented collaboration in the multinational pharmaceutical industry and between governments.[197] By June 2020, tens of billions of dollars were invested by corporations, governments, international health organizations, and university research groups to develop dozens of vaccine candidates and prepare for global vaccination programs to immunize against COVID‑19 infection.[195][198][199][200] According to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the geographic distribution of COVID‑19 vaccine development shows North American entities to have about 40% of the activity, compared to 30% in Asia and Australia, 26% in Europe, and a few projects in South America and Africa.[194][197]

In February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) said it did not expect a vaccine against SARS‑CoV‑2 to become available in less than 18 months.[201] Virologist Paul Offit commented that, in hindsight, the development of a safe and effective vaccine within 11 months was a remarkable feat.[202] The rapidly growing infection rate of COVID‑19 worldwide during 2020 stimulated international alliances and government efforts to urgently organize resources to make multiple vaccines on shortened timelines,[203] with four vaccine candidates entering human evaluation in March (see COVID-19 vaccine § Trial and authorization status).[194][204]

On 24 June 2020, China approved the CanSino vaccine for limited use in the military and two inactivated virus vaccines for emergency use in high-risk occupations.[205] On 11 August 2020, Russia announced the approval of its Sputnik V vaccine for emergency use, though one month later only small amounts of the vaccine had been distributed for use outside of the phase 3 trial.[206]

The Pfizer–BioNTech partnership submitted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 (active ingredient tozinameran) on 20 November 2020.[207][208] On 2 December 2020, the United Kingdom's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) gave temporary regulatory approval for the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine,[209][210] becoming the first country to approve the vaccine and the first country in the Western world to approve the use of any COVID‑19 vaccine.[211][212][213] As of 21 December 2020, many countries and the European Union[214] had authorized or approved the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine. Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates granted emergency marketing authorization for the Sinopharm BIBP vaccine.[215][216] On 11 December 2020, the FDA granted an EUA for the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine.[217] A week later, they granted an EUA for mRNA-1273 (active ingredient elasomeran), the Moderna vaccine.[218][219][220][221]

On 31 March 2021, the Russian government announced that they had registered the first COVID‑19 vaccine for animals.[222] Named Carnivac-Cov, it is an inactivated vaccine for carnivorous animals, including pets, aimed at preventing mutations that occur during the interspecies transmission of SARS-CoV-2.[223]

In October 2022, China began administering an oral vaccine developed by CanSino Biologics using its adenovirus model.[224]

Despite the availability of mRNA and viral vector vaccines, worldwide vaccine equity has not been achieved. The ongoing development and use of whole inactivated virus (WIV) and protein-based vaccines has been recommended, especially for use in developing countries, to dampen further waves of the pandemic.[225][226]In November 2021, the full nucleotide sequences of the AstraZeneca and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines were released by the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in response to a freedom of information request.[227][228]

Effectiveness

Evidence from vaccine use during the pandemic shows vaccination can reduce infection and is most effective at preventing severe COVID-19 symptoms and death, but is less good at preventing mild COVID-19. Efficacy wanes over time but can be maintained with boosters.[231] In 2021, the CDC reported that unvaccinated people were 10 times more likely to be hospitalized and 11 times more likely to die than fully vaccinated people.[232][233]

The CDC reported that vaccine effectiveness fell from 91% against Alpha to 66% against Delta.[234] One expert stated that "those who are infected following vaccination are still not getting sick and not dying like was happening before vaccination."[235] By late August 2021, the Delta variant accounted for 99 percent of U.S. cases and was found to double the risk of severe illness and hospitalization for those not yet vaccinated.[236]

In November 2021, a study by the ECDC estimated that 470,000 lives over the age of 60 had been saved since the start of the vaccination roll-out in the European region.[237]

On 10 December 2021, the UK Health Security Agency reported that early data indicated a 20- to 40-fold reduction in neutralizing activity for Omicron by sera from Pfizer 2-dose vaccinees relative to earlier strains. After a booster dose (usually with an mRNA vaccine),[238] vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic disease was at 70%–75%, and the effectiveness against severe disease was expected to be higher.[239]

According to early December 2021 CDC data, "unvaccinated adults were about 97 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than fully vaccinated people who had received boosters".[240]

A meta-analysis looking into COVID-19 vaccine differences in immunosuppressed individuals found that people with a weakened immune system are less able to produce neutralizing antibodies. For example, organ transplant recipients need three vaccines to achieve seroconversion.[241] A study on the serologic response to mRNA vaccines among patients with lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma found that one-quarter of patients did not produce measurable antibodies, varying by cancer type.[242]

In February 2023, a systematic review in The Lancet said that the protection afforded by infection was comparable to that from vaccination, albeit with an increased risk of severe illness and death from the disease of an initial infection.[243]

A January 2024 study by the CDC found that staying up to date on the vaccines could reduce the risk of strokes, blood clots and heart attacks related to COVID-19 in people aged 65 years or older or with a condition that makes them more vulnerable to said conditions.[244][245]An analysis involving more than 20 million adults found that vaccinated people had a lower risk of long COVID compared to those who had not had a COVID-19 vaccine.[246][247]

Duration of immunity

As of 2021, available evidence shows that fully vaccinated individuals and those previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 have a low risk of subsequent infection for at least six months.[248][249][250] There is insufficient data to determine an antibody titer threshold that indicates when an individual is protected from infection.[248] Multiple studies show that antibody titers are associated with protection at the population level, but individual protection titers remain unknown.[248] For some populations, such as the elderly and the immunocompromised, protection levels may be reduced after both vaccination and infection.[248] Available evidence indicates that the level of protection may not be the same for all variants of the virus.[248]

As of December 2021, there are no FDA-authorized or approved tests that providers or the public can use to determine if a person is protected from infection reliably.[248]

As of March 2022, elderly residents' protection against severe illness, hospitalization, and death in English care homes was high immediately after vaccination, but protection declined significantly in the months following vaccination.[251] Protection among care home staff, who were younger, declined much more slowly.[251] Regular boosters are recommended for older people, and boosters for care home residents every six months appear reasonable.[251]

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a fourth dose of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine as of March 2022[update] for "certain immunocompromised individuals and people over the age of 50".[252][253]

Immune evasion by variants

In contrast to other investigated prior variants, the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant[254][255][256][257][258] and its BA.4/5 subvariants[259] have evaded immunity induced by vaccines, which may lead to breakthrough infections despite recent vaccination. Nevertheless, vaccines are thought to provide protection against severe illness, hospitalizations, and deaths due to Omicron.[260]

Vaccine adjustments

In June 2022, Pfizer and Moderna developed bivalent vaccines to protect against the SARS-CoV-2 wild-type and the Omicron variant. The bivalent vaccines are well-tolerated and offer immunity to Omicron superior to previous mRNA vaccines.[261] In September 2022, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the bivalent vaccines.[262][263][264]

In June 2023, the FDA advised manufacturers that the 2023–2024 formulation of the COVID‑19 vaccines for use in the US be updated to be a monovalent COVID‑19 vaccine using the XBB.1.5 lineage of the Omicron variant.[265][266] In June 2024, the FDA advised manufacturers that the 2024–2025 formulation of the COVID‑19 vaccines for use in the US be updated to be a monovalent COVID‑19 vaccine using the JN.1 lineage.[267]

In October 2024, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) gave a positive opinion to update the composition of Bimervax, a vaccine targeting the Omicron XBB.1.16 subvariant.[268]Effectiveness against transmission

As of 2022, fully vaccinated individuals with breakthrough infections with the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant have a peak viral load similar to unvaccinated cases and can transmit infection in household settings.[269]

Mix and match

According to studies, the combination of two different COVID‑19 vaccines, also called heterologous vaccination, cross-vaccination, or the mix-and-match method, provides protection equivalent to that of mRNA vaccines, including protection against the Delta variant. Individuals who receive the combination of two different vaccines produce strong immune responses, with side effects no worse than those caused by standard regimens.[270][271]

Drug interactions

Methotrexate reduces the immune response to COVID-19 vaccines, making them less effective.[272][273] Pausing methotrexate for two weeks following COVID-19 vaccination may result in improved immunity. Not taking the medicine for two weeks might result in a minor increase of inflammatory disease flares in some people.[274][275][276]

Adverse events

For most people, the side effects, also called adverse effects, from COVID‑19 vaccines are mild and can be managed at home. The adverse effects of the COVID‑19 vaccination are similar to those of other vaccines, and severe adverse effects are rare.[277][278] Adverse effects from the vaccine are higher than placebo, but placebo arms of vaccine trials still reported adverse effects that can be attributed to the nocebo effect.[279]

All vaccines that are administered via intramuscular injection, including COVID‑19 vaccines, have side effects related to the mild trauma associated with the procedure and the introduction of a foreign substance into the body.[280] These include soreness, redness, rash, and inflammation at the injection site. Other common side effects include fatigue, headache, myalgia (muscle pain), and arthralgia (joint pain), all of which generally resolve without medical treatment within a few days.[13][14] Like any other vaccine, some people are allergic to one or more ingredients in COVID‑19 vaccines. Typical side effects are stronger and more common in younger people and in subsequent doses, and up to 20% of people report a disruptive level of side effects after the second dose of an mRNA vaccine.[281] These side effects are less common or weaker in inactivated vaccines.[281] COVID‑19 vaccination-related enlargement of lymph nodes happens in 11.6% of those who received one dose of the vaccine and in 16% of those who received two doses.[282]

Experiments in mice show that intramuscular injections of lipid excipient nanoparticles (an inactive substance that serves as the vehicle or medium) cause particles to enter the blood plasma and many organs, with higher concentrations found in the liver and lower concentrations in the spleen, adrenal glands, and ovaries. The highest concentration of nanoparticles was found at the injection site itself.[283]

COVID‑19 vaccination is safe for breastfeeding people.[15] Temporary changes to the menstrual cycle in young women have been reported. However, these changes are "small compared with natural variation and quickly reverse."[284] In one study, women who received both doses of a two-dose vaccine during the same menstrual cycle (an atypical situation) may see their next period begin a couple of days late. They have about twice the usual risk of a clinically significant delay (about 10% of these women, compared to about 4% of unvaccinated women).[284] Cycle lengths return to normal after two menstrual cycles post-vaccination.[284] Women who received doses in separate cycles had approximately the same natural variation in cycle lengths as unvaccinated women.[284] Other temporary menstrual effects have been reported, such as heavier than normal menstrual bleeding after vaccination.[284]

Serious adverse events associated COVID‑19 vaccines are generally rare but of high interest to the public.[285] The official databases of reported adverse events include

- the World Health Organization's VigiBase;

- the United States Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS);

- the United Kingdom's Yellow Card Scheme;

- the European Medicines Agency's EudraVigilance system, which operates a regular transfer of data on suspected adverse drug reactions occurring in the EU to WHO's Uppsala Monitoring Centre.[286]

Increased public awareness of these reporting systems and the extra reporting requirements under US FDA Emergency Use Authorization rules have increased reported adverse events.[287] Serious side effects are an ongoing area of study, and resources have been allocated to try to better understand them.[288][289][290] Research currently indicates that the rate and type of side effects are lower-risk than infection. For example, although vaccination may trigger some side effects, the effects experienced from an infection could be worse. Neurological side effects from getting COVID‑19 are hundreds of times more likely than from vaccination.[291]

Documented rare serious effects include:

- anaphylaxis, a severe type of allergic reaction.[292] Anaphylaxis affects one person per 250,000 to 400,000 doses administered.[281][293] According to a 2022 systematic review, the mortality rate of people with anaphylaxis following COVID‐19 vaccination was 0,5%.[294]

- blood clots (thrombosis).[292] These vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis are associated with vaccines using an adenovirus system (Janssen and Oxford-AstraZeneca).[292] These affect about one person per 100,000.[281]

- myocarditis and pericarditis, or inflammation of the heart.[292] There is a rare risk of myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) or pericarditis (inflammation of the membrane covering the heart) after the mRNA COVID‑19 vaccines (Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech). The risk of myocarditis after COVID‑19 vaccination is estimated to be 0.3 to 5 cases per 100,000 persons, with the highest risk in young males.[295] In an Israeli nation-wide population-based study (in which the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was exclusively given), the incidence rate of myocarditis was 54 cases out of 2.5 million vaccine recipients, with an overall incidence rate of 2 cases per 100,000 persons, with the highest incidence seen in young males (aged 16 to 29) at 10 cases per 100,000 vaccine recipients. Of the cases of myocarditis seen, 76% were mild in severity, with one case of cardiogenic shock (heart failure) and one death (in a person with a preexisting heart condition) reported within the 83-day follow-up period.[296] COVID‑19 vaccines may protect against myocarditis due to subsequent COVID‑19 infection.[297] The risk of myocarditis and pericarditis is significantly higher (up to 11 times higher with respect to myocarditis) after COVID‑19 infection as compared to COVID‑19 vaccination, with the possible exception of younger men (less than 40 years old) who may have a higher risk of myocarditis after the second Moderna mRNA vaccine (an additional 97 cases of myocarditis per 1 million persons vaccinated).[297] The mortality rate from myocarditis post-vaccination is extremely low. According to a 2022 study, of patients diagnosed with myocarditis (in both vaccination and COVID-19 cohort) 1.07% were hospitalized and 0.015% died.[298]

- thrombotic thrombocytopenia and other autoimmune diseases, which have been reported as adverse events after the COVID‑19 vaccine.[299]

There are rare reports of subjective hearing changes, including tinnitus, after vaccination.[293][300][301][302]

Society and culture

Distribution

Note about the table in this section: number and percentage of people who have received at least one dose of a COVID‑19 vaccine (unless noted otherwise). May include vaccination of non-citizens, which can push totals beyond 100% of the local population. The table is updated daily by a bot.[note 2]

| Location | Vaccinated[b] | Percent[c] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World[d][e] | 5,645,247,500 | 70.70% | |

| China[f] | 1,318,026,800 | 92.48% | |

| India | 1,027,438,900 | 72.08% | |

| European Union[g] | 338,481,060 | 75.43% | |

| United States[h] | 270,227,170 | 79.12% | |

| Indonesia | 204,419,400 | 73.31% | |

| Brazil | 189,643,420 | 90.17% | |

| Pakistan | 165,567,890 | 67.94% | |

| Bangladesh | 151,507,170 | 89.45% | |

| Japan | 104,740,060 | 83.79% | |

| Mexico | 97,179,496 | 75.56% | |

| Nigeria | 93,829,430 | 42.05% | |

| Vietnam | 90,497,670 | 90.79% | |

| Russia | 89,081,600 | 61.19% | |

| Philippines | 82,684,776 | 72.55% | |

| Iran | 65,199,830 | 72.83% | |

| Germany | 64,876,300 | 77.15% | |

| Turkey | 57,941,052 | 66.55% | |

| Thailand | 57,005,496 | 79.47% | |

| Egypt | 56,907,320 | 50.53% | |

| France | 54,677,680 | 82.50% | |

| United Kingdom | 53,806,964 | 78.92% | |

| Ethiopia | 52,489,510 | 41.86% | |

| Italy[i] | 50,936,720 | 85.44% | |

| South Korea | 44,764,956 | 86.45% | |

| Colombia | 43,012,176 | 83.13% | |

| Myanmar | 41,551,930 | 77.30% | |

| Argentina | 41,529,056 | 91.46% | |

| Spain | 41,351,230 | 86.46% | |

| Canada | 34,742,936 | 89.49% | |

| Tanzania | 34,434,932 | 53.21% | |

| Peru | 30,563,708 | 91.30% | |

| Malaysia | 28,138,564 | 81.10% | |

| Nepal | 27,883,196 | 93.83% | |

| Saudi Arabia | 27,041,364 | 84.04% | |

| Morocco | 25,020,168 | 67.03% | |

| South Africa | 24,210,952 | 38.81% | |

| Poland | 22,984,544 | 59.88% | |

| Mozambique | 22,869,646 | 70.03% | |

| Australia | 22,231,734 | 84.85% | |

| Venezuela | 22,157,232 | 78.54% | |

| Uzbekistan | 22,094,470 | 63.24% | |

| Taiwan | 21,899,240 | 93.51% | |

| Uganda | 20,033,188 | 42.34% | |

| Afghanistan | 19,151,368 | 47.20% | |

| Chile | 18,088,516 | 92.51% | |

| Sri Lanka | 17,143,760 | 75.08% | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 17,045,720 | 16.65% | |

| Angola | 16,550,642 | 46.44% | |

| Ukraine | 16,267,198 | 39.63% | |

| Ecuador | 15,345,791 | 86.10% | |

| Cambodia | 15,316,670 | 89.04% | |

| Sudan | 15,207,452 | 30.79% | |

| Kenya | 14,494,372 | 26.72% | |

| Ghana | 13,864,186 | 41.82% | |

| Ivory Coast | 13,568,372 | 44.64% | |

| Netherlands | 12,582,081 | 70.27% | |

| Zambia | 11,711,565 | 58.11% | |

| Iraq | 11,332,925 | 25.72% | |

| Rwanda | 10,884,714 | 79.74% | |

| Kazakhstan | 10,858,101 | 54.20% | |

| Cuba | 10,805,570 | 97.70% | |

| United Arab Emirates | 9,991,089 | 97.55% | |

| Portugal | 9,821,414 | 94.28% | |

| Belgium | 9,261,641 | 79.55% | |

| Somalia | 8,972,167 | 50.40% | |

| Guatemala | 8,937,923 | 50.08% | |

| Tunisia | 8,896,848 | 73.41% | |

| Guinea | 8,715,641 | 62.01% | |

| Greece | 7,938,031 | 76.24% | |

| Algeria | 7,840,131 | 17.24% | |

| Sweden | 7,775,726 | 74.14% | |

| Zimbabwe | 7,525,882 | 46.83% | |

| Dominican Republic | 7,367,193 | 65.60% | |

| Bolivia | 7,361,008 | 60.95% | |

| Israel | 7,055,466 | 77.51% | |

| Czech Republic | 6,982,006 | 65.42% | |

| Hong Kong | 6,920,057 | 92.69% | |

| Austria | 6,899,873 | 76.12% | |

| Honduras | 6,596,213 | 63.04% | |

| Belarus | 6,536,392 | 71.25% | |

| Hungary | 6,420,354 | 66.30% | |

| Nicaragua | 6,404,524 | 95.15% | |

| Niger | 6,248,483 | 24.69% | |

| Switzerland | 6,096,911 | 69.34% | |

| Burkina Faso | 6,089,089 | 27.05% | |

| Laos | 5,888,649 | 77.90% | |

| Sierra Leone | 5,676,123 | 68.58% | |

| Romania | 5,474,507 | 28.56% | |

| Malawi | 5,433,538 | 26.42% | |

| Azerbaijan | 5,373,253 | 52.19% | |

| Tajikistan | 5,328,277 | 52.33% | |

| Singapore | 5,287,005 | 93.58% | |

| Chad | 5,147,667 | 27.89% | |

| Jordan | 4,821,579 | 42.83% | |

| Denmark | 4,746,522 | 80.41% | |

| El Salvador | 4,659,970 | 74.20% | |

| Costa Rica | 4,650,636 | 91.52% | |

| Turkmenistan | 4,614,869 | 63.83% | |

| Finland | 4,524,288 | 81.24% | |

| Mali | 4,354,292 | 18.87% | |

| Norway | 4,346,995 | 79.66% | |

| South Sudan | 4,315,127 | 39.15% | |

| New Zealand | 4,302,330 | 83.84% | |

| Republic of Ireland | 4,112,237 | 80.47% | |

| Paraguay | 3,995,915 | 59.11% | |

| Liberia | 3,903,802 | 72.65% | |

| Cameroon | 3,753,733 | 13.58% | |

| Panama | 3,746,041 | 85.12% | |

| Benin | 3,697,190 | 26.87% | |

| Kuwait | 3,457,498 | 75.33% | |

| Serbia | 3,354,075 | 49.39% | |

| Syria | 3,295,630 | 14.67% | |

| Oman | 3,279,632 | 69.33% | |

| Uruguay | 3,010,464 | 88.78% | |

| Qatar | 2,852,178 | 98.61% | |

| Slovakia | 2,840,017 | 51.89% | |

| Lebanon | 2,740,227 | 47.70% | |

| Madagascar | 2,710,365 | 8.90% | |

| Senegal | 2,684,696 | 15.21% | |

| Central African Republic | 2,600,389 | 51.01% | |

| Croatia | 2,323,025 | 59.46% | |

| Libya | 2,316,327 | 32.07% | |

| Mongolia | 2,284,018 | 67.45% | |

| Togo | 2,255,579 | 24.81% | |

| Bulgaria | 2,155,863 | 31.58% | |

| Mauritania | 2,103,754 | 43.15% | |

| Palestine | 2,012,767 | 37.94% | |

| Lithuania | 1,958,299 | 69.52% | |

| Botswana | 1,951,054 | 79.96% | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 1,736,541 | 24.97% | |

| Georgia | 1,654,504 | 43.60% | |

| Albania | 1,349,255 | 47.72% | |

| Latvia | 1,346,184 | 71.57% | |

| Slovenia | 1,265,802 | 59.84% | |

| Bahrain | 1,241,174 | 80.94% | |

| Armenia | 1,150,915 | 39.95% | |

| Mauritius | 1,123,773 | 88.06% | |

| Moldova | 1,109,524 | 36.50% | |

| Yemen | 1,050,202 | 2.75% | |

| Lesotho | 1,014,073 | 44.36% | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 943,394 | 29.44% | |

| Kosovo | 906,858 | 52.79% | |

| Timor-Leste | 886,838 | 64.77% | |

| Estonia | 870,202 | 64.46% | |

| Jamaica | 859,773 | 30.28% | |

| North Macedonia | 854,570 | 46.44% | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 754,399 | 50.43% | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 747,057 | 35.48% | |

| Fiji | 712,025 | 77.44% | |

| Bhutan | 699,116 | 89.52% | |

| Republic of the Congo | 695,760 | 11.53% | |

| Macau | 679,703 | 96.50% | |

| Gambia | 674,314 | 25.58% | |

| Cyprus | 671,193 | 71.37% | |

| Namibia | 629,767 | 21.79% | |

| Eswatini | 526,050 | 43.16% | |

| Haiti | 521,396 | 4.53% | |

| Guyana | 497,550 | 60.56% | |

| Luxembourg | 481,957 | 73.77% | |

| Malta | 478,953 | 90.68% | |

| Brunei | 451,149 | 99.07% | |

| Comoros | 438,825 | 52.60% | |

| Djibouti | 421,573 | 37.07% | |

| Maldives | 399,308 | 76.19% | |

| Papua New Guinea | 382,020 | 3.74% | |

| Cabo Verde | 356,734 | 68.64% | |

| Solomon Islands | 343,821 | 44.02% | |

| Gabon | 311,244 | 12.80% | |

| Iceland | 309,770 | 81.44% | |

| Northern Cyprus | 301,673 | 78.80% | |

| Montenegro | 292,783 | 47.63% | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 270,109 | 14.98% | |

| Suriname | 267,820 | 42.98% | |

| Belize | 258,473 | 64.18% | |

| New Caledonia | 192,375 | 67.00% | |

| Samoa | 191,403 | 88.91% | |

| French Polynesia | 190,908 | 68.09% | |

| Vanuatu | 176,624 | 56.42% | |

| Bahamas | 174,810 | 43.97% | |

| Barbados | 163,853 | 58.04% | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 140,256 | 61.97% | |

| Curaçao | 108,601 | 58.59% | |

| Kiribati | 100,900 | 77.33% | |

| Aruba | 90,546 | 84.00% | |

| Seychelles | 88,520 | 70.52% | |

| Tonga | 87,375 | 83.17% | |

| Jersey | 84,365 | 81.52% | |

| Isle of Man | 69,560 | 82.67% | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 64,290 | 69.24% | |

| Cayman Islands | 62,113 | 86.74% | |

| Saint Lucia | 60,140 | 33.64% | |

| Andorra | 57,913 | 72.64% | |

| Guernsey | 54,223 | 85.06% | |

| Bermuda | 48,554 | 74.96% | |

| Grenada | 44,241 | 37.84% | |

| Gibraltar | 42,175 | 112.08% | |

| Faroe Islands | 41,715 | 77.19% | |

| Greenland | 41,227 | 73.60% | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 37,532 | 36.77% | |

| Burundi | 36,909 | 0.28% | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 33,794 | 72.32% | |

| Dominica | 32,995 | 49.36% | |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 32,815 | 71.54% | |

| Sint Maarten | 29,788 | 70.65% | |

| Monaco | 28,875 | 74.14% | |

| Liechtenstein | 26,771 | 68.06% | |

| San Marino | 26,357 | 77.26% | |

| British Virgin Islands | 19,466 | 50.77% | |

| Caribbean Netherlands | 19,109 | 66.69% | |

| Cook Islands | 15,112 | 102.48% | |

| Nauru | 13,106 | 110.87% | |

| Anguilla | 10,858 | 76.45% | |

| Tuvalu | 9,763 | 97.51% | |

| Wallis and Futuna | 7,150 | 62.17% | |

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | 4,361 | 81.23% | |

| Falkland Islands | 2,632 | 74.88% | |

| Tokelau | 2,203 | 95.29% | |

| Montserrat | 2,104 | 47.01% | |

| Niue | 1,638 | 88.83% | |

| Pitcairn Islands | 47 | 100.00% | |

| North Korea | 0 | 0.00% | |

| |||

As of 12 August 2024[update], 13.53 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered worldwide, with 70.6 percent of the global population having received at least one dose.[304][305] While 4.19 million vaccines were then being administered daily, only 22.3 percent of people in low-income countries had received at least a first vaccine by September 2022, according to official reports from national health agencies, which are collated by Our World in Data.[306]

During a pandemic on the rapid timeline and scale of COVID-19 cases in 2020, international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), vaccine developers, governments, and industry evaluated the distribution of the eventual vaccine(s).[307] Individual countries producing a vaccine may be persuaded to favor the highest bidder for manufacturing or provide first-class service to their own country.[308][309][310] Experts emphasize that licensed vaccines should be available and affordable for people at the frontlines of healthcare and in most need.[308][310]

In April 2020, it was reported that the UK agreed to work with 20 other countries and global organizations, including France, Germany, and Italy, to find a vaccine and share the results, and that UK citizens would not get preferential access to any new COVID‑19 vaccines developed by taxpayer-funded UK universities.[311] Several companies planned to initially manufacture a vaccine at artificially low prices, then increase prices for profitability later if annual vaccinations are needed and as countries build stock for future needs.[310]

The WHO had set out the target to vaccinate 40% of the population of all countries by the end of 2021 and 70% by mid-2022,[312] but many countries missed the 40% target at the end of 2021.[313][314]- Share of people who have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine relative to a country's total population. The date is on the map. Commons source.

- COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people by country. The date is on the map. Commons source.

Access

Countries have extremely unequal access to the COVID‑19 vaccine. Vaccine equity has not been achieved or even approximated. The inequity has harmed both countries with poor access and countries with good access.[19][20][315]

Nations pledged to buy doses of the COVID‑19 vaccines before the doses were available. Though high-income nations represent only 14% of the global population, as of 15 November 2020, they had contracted to buy 51% of all pre-sold doses. Some high-income nations bought more doses than would be necessary to vaccinate their entire populations.[18]

In January 2021, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned of problems with equitable distribution: "More than 39 million doses of vaccine have now been administered in at least 49 higher-income countries. Just 25 doses have been given in one lowest-income country. Not 25 million; not 25 thousand; just 25."[316]

In March 2021, it was revealed that the US attempted to convince Brazil not to purchase the Sputnik V COVID‑19 vaccine, fearing "Russian influence" in Latin America.[317] Some nations involved in long-standing territorial disputes have reportedly had their access to vaccines blocked by competing nations; Palestine has accused Israel of blocking vaccine delivery to Gaza, while Taiwan has suggested that China has hampered its efforts to procure vaccine doses.[318][319][320]

A single dose of the COVID‑19 vaccines by AstraZeneca would cost 47 Egyptian pounds (EGP), and the authorities are selling them for between 100 and 200 EGP. A report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace cited the poverty rate in Egypt as around 29.7 percent, which constitutes approximately 30.5 million people, and claimed that about 15 million Egyptians would be unable to gain access to the luxury of vaccination. A human rights lawyer, Khaled Ali, launched a lawsuit against the government, forcing them to provide vaccinations free of charge to all members of the public.[321]

According to immunologist Anthony Fauci, mutant strains of the virus and limited vaccine distribution pose continuing risks, and he said, "we have to get the entire world vaccinated, not just our own country."[322] Edward Bergmark and Arick Wierson are calling for a global vaccination effort and wrote that the wealthier nations' "me-first" mentality could ultimately backfire because the spread of the virus in poorer countries would lead to more variants, against which the vaccines could be less effective.[323]

In March 2021, the United States, Britain, European Union member states, and some other members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) blocked a push by more than eighty developing countries to waive COVID‑19 vaccine patent rights in an effort to boost production of vaccines for poor nations.[324] On 5 May 2021, the US government under President Joe Biden announced that it supports waiving intellectual property protections for COVID‑19 vaccines.[325] The Members of the European Parliament have backed a motion demanding the temporary lifting of intellectual property rights for COVID‑19 vaccines.[326]

In a meeting in April 2021, the World Health Organization's emergency committee addressed concerns of persistent inequity in global vaccine distribution.[327] Although 9 percent of the world's population lives in the 29 poorest countries, these countries had received only 0.3% of all vaccines administered as of May 2021.[328] In March 2021, Brazilian journalism agency Agência Pública reported that the country vaccinated about twice as many people who declare themselves white than black and noted that mortality from COVID‑19 is higher in the black population.[329]

In May 2021, UNICEF made an urgent appeal to industrialized nations to pool their excess COVID‑19 vaccine capacity to make up for a 125-million-dose gap in the COVAX program. The program mostly relied on the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‑19 vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India, which faced serious supply problems due to increased domestic vaccine needs in India from March to June 2021. Only a limited amount of vaccines can be distributed efficiently, and the shortfall of vaccines in South America and parts of Asia is due to a lack of expedient donations by richer nations. International aid organizations have pointed at Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives, as well as Argentina, Brazil, and some parts of the Caribbean, as problem areas where vaccines are in short supply. In mid-May 2021, UNICEF was also critical of the fact that most proposed donations of Moderna and Pfizer vaccines were not slated for delivery until the second half of 2021 or early in 2022.[330]

In July 2021, the heads of the World Bank Group, the International Monetary Fund, the World Health Organization, and the World Trade Organization said in a joint statement: "As many countries are struggling with new variants and a third wave of COVID‑19 infections, accelerating access to vaccines becomes even more critical to ending the pandemic everywhere and achieving broad-based growth. We are deeply concerned about the limited vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and support for deliveries available to developing countries."[331][332] In July 2021, The BMJ reported that countries had thrown out over 250,000 vaccine doses as supply exceeded demand and strict laws prevented the sharing of vaccines.[333] A survey by The New York Times found that over a million doses of vaccine had been thrown away in ten U.S. states because federal regulations prohibit recalling them, preventing their redistribution abroad.[334] Furthermore, doses donated close to expiration often cannot be administered quickly enough by recipient countries and end up having to be discarded.[335] To help overcome this problem, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, announced that they would make their digital vaccination management platform, CoWIN, open to the global community. He also announced that India would also release the source code for the contact tracing app Aarogya Setu for developers around the world. Around 142 countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Guyana, Antigua and Barbuda, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Zambia, expressed their interest in the application for COVID management.[336][337]

Amnesty International and Oxfam International have criticized the support of vaccine monopolies by the governments of producing countries, noting that this is dramatically increasing the dose price by five times and often much more, creating an economic barrier to access for poor countries.[338][339] Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders) has also criticized vaccine monopolies and repeatedly called for their suspension, supporting the TRIPS waiver. The waiver was first proposed in October 2020 and has support from most countries, but was delayed by opposition from the EU (especially Germany; major EU countries such as France, Italy, and Spain support the exemption),[340] the UK, Norway, and Switzerland, among others. MSF called for a Day of Action in September 2021 to put pressure on the WTO Minister's meeting in November, which was expected to discuss the TRIPS IP waiver.[341][342][343]

In August 2021, to reduce unequal distribution between rich and poor countries, the WHO called for a moratorium on booster doses at least until the end of September. However, in August, the United States government announced plans to offer booster doses eight months after the initial course to the general population, starting with priority groups. Before the announcement, the WHO harshly criticized this type of decision, citing the lack of evidence for the need for boosters, except for patients with specific conditions. At this time, vaccine coverage of at least one dose was 58% in high-income countries and only 1.3% in low-income countries, and 1.14 million Americans had already received an unauthorized booster dose. US officials argued that waning efficacy against mild and moderate disease might indicate reduced protection against severe disease in the coming months. Israel, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom have also started planning boosters for specific groups.[344][345][346] In September 2021, more than 140 former world leaders and Nobel laureates, including former President of France François Hollande, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Gordon Brown, former Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark, and Professor Joseph Stiglitz, called on the candidates to be the next German chancellor to declare themselves in favor of waiving intellectual property rules for COVID‑19 vaccines and transferring vaccine technologies.[347] In November 2021, nursing unions in 28 countries filed a formal appeal with the United Nations over the refusal of the UK, EU, Norway, Switzerland, and Singapore to temporarily waive patents for COVID‑19 vaccines.[348]

During his first international trip, the President of Peru, Pedro Castillo, spoke at the seventy-sixth session of the United Nations General Assembly on 21 September 2021, proposing the creation of an international treaty signed by world leaders and pharmaceutical companies to guarantee universal vaccine access, arguing that "The battle against the pandemic has shown us the failure of the international community to cooperate under the principle of solidarity."[349][350]

Optimizing the societal benefit of vaccination may benefit from a strategy that is tailored to the state of the pandemic, the demographics of a country, the age of the recipients, the availability of vaccines, and the individual risk for severe disease.[12] In the UK, the interval between prime and booster doses was extended to vaccinate as many people as early as possible.[351] Many countries are starting to give an additional booster shot to the immunosuppressed[352][353] and the elderly,[354] and research predicts an additional benefit of personalizing vaccine doses in the setting of limited vaccine availability when a wave of virus Variants of Concern hits a country.[355]

Despite the extremely rapid development of effective mRNA and viral vector vaccines, vaccine equity has not been achieved.[19] The World Health Organization called for 70 percent of the global population to be vaccinated by mid-2022, but as of March 2022, it was estimated that only one percent of the 10 billion doses given worldwide had been administered in low-income countries.[356] An additional 6 billion vaccinations may be needed to fill vaccine access gaps, particularly in developing countries. Given the projected availability of newer vaccines, the development and use of whole inactivated virus (WIV) and protein-based vaccines are also recommended. Organizations such as the Developing Countries Vaccine Manufacturers Network could help to support the production of such vaccines in developing countries, with lower production costs and greater ease of deployment.[19][357]

While vaccines substantially reduce the probability and severity of infection, it is still possible for fully vaccinated people to contract and spread COVID‑19.[358] Public health agencies have recommended that vaccinated people continue using preventive measures (wear face masks, social distance, wash hands) to avoid infecting others, especially vulnerable people, particularly in areas with high community spread. Governments have indicated that such recommendations will be reduced as vaccination rates increase and community spread declines.[359]

Economics

Moreover, an unequal distribution of vaccines will deepen inequality and exaggerate the gap between rich and poor and will reverse decades of hard-won progress on human development.

— United Nations, COVID vaccines: Widening inequality and millions vulnerable[360]

Vaccine inequity damages the global economy, disrupting the global supply chain.[315] Most vaccines were reserved for wealthy countries; as of September 2021[update],[360] some countries have more vaccines than are needed to fully vaccinate their populations.[18] When people are under-vaccinated, needlessly die, experience disability, and live under lockdown restrictions, they cannot supply the same goods and services. This harms the economies of under-vaccinated and over-vaccinated countries alike. Since rich countries have larger economies, rich countries may lose more money to vaccine inequity than poor ones,[315] though the poor ones will lose a higher percentage of GDP and experience longer-term effects.[361] High-income countries would profit an estimated US$4.80 for every $1 spent on giving vaccines to lower-income countries.[315]

The International Monetary Fund sees the vaccine divide between rich and poor nations as a serious obstacle to a global economic recovery.[362] Vaccine inequity disproportionately affects refuge-providing states, as they tend to be poorer, and refugees and displaced people are economically more vulnerable even within those low-income states, so they have suffered more economically from vaccine inequity.[363][19]

Liability

Several governments agreed to shield pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Moderna from negligence claims related to COVID‑19 vaccines (and treatments), as in previous pandemics, when governments also took on liability for such claims.

In the US, these liability shields took effect on 4 February 2020, when the US Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, published a notice of declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act (PREP Act) for medical countermeasures against COVID‑19, covering "any vaccine, used to treat, diagnose, cure, prevent, or mitigate COVID‑19, or the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or a virus mutating therefrom". The declaration precludes "liability claims alleging negligence by a manufacturer in creating a vaccine, or negligence by a health care provider in prescribing the wrong dose, absent willful misconduct." In other words, absent "willful misconduct", these companies cannot be sued for money damages for any injuries that occur between 2020 and 2024 from the administration of vaccines and treatments related to COVID‑19.[364] The declaration is effective in the United States through 1 October 2024.[364]

In December 2020, the UK government granted Pfizer legal indemnity for its COVID‑19 vaccine.[365]

In the European Union, the COVID‑19 vaccines were granted a conditional marketing authorization, which does not exempt manufacturers from civil and administrative liability claims.[366] The EU conditional marketing authorizations were changed to standard authorizations in September 2022.[367] While the purchasing contracts with vaccine manufacturers remain secret, they do not contain liability exemptions, even for side effects not known at the time of licensure.[368]

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit news organization, reported in an investigation that unnamed officials in some countries, such as Argentina and Brazil, said that Pfizer demanded guarantees against costs of legal cases due to adverse effects in the form of liability waivers and sovereign assets such as federal bank reserves, embassy buildings, or military bases, going beyond what was expected from other countries, such as the US.[369] During the pandemic parliamentary inquiry in Brazil, Pfizer's representative said that its terms for Brazil are the same as for all other countries with which it has signed deals.[370]

On 13 December 2022, the governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis, said that he would petition the state supreme court to convene a grand jury to investigate possible violations in respect to COVID‑19 vaccines,[371] and declared that his government would be able to get "the data whether they [the companies] want to give it or not".[372]

On 30 November 2023, the U.S. state of Texas sued Pfizer under section 17.47 of the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act, alleging that the company misled the public about its Covid-19 vaccine by hiding risks while making false claims about its effectiveness.[373][374] On 17 June 2024, the U.S. state of Kansas similarly sued Pfizer under the Kansas Consumer Protection Act, making similar allegations.[375]

Controversy

In June 2021, a report revealed that the UB-612 vaccine, developed by the US-based Covaxx, was a for-profit venture initiated by Blackwater founder Erik Prince. In a series of text messages to Paul Behrends, the close associate recruited for the Covaxx project, Prince described the profit-making possibilities of selling the COVID‑19 vaccines. Covaxx provided no data from the clinical trials on safety or efficacy it conducted in Taiwan. The responsibility of creating distribution networks was assigned to an Abu Dhabi-based entity, which was mentioned as "Windward Capital" on the Covaxx letterhead but was actually Windward Holdings. The firm's sole shareholder, who handled "professional, scientific and technical activities", was Erik Prince. In March 2021, Covaxx raised $1.35 billion in a private placement.[376]

Misinformation and hesitancy

In many countries a variety of unfounded conspiracy theories and other misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines have spread based on misunderstood or misrepresented science, religion, and law. These have included exaggerated claims about side effects, misrepresentations about how the immune system works and when and how COVID-19 vaccines are made, a story about COVID-19 being spread by 5G, and other false or distorted information. This misinformation, some created by anti-vaccination activists, has proliferated and may have made many people averse to vaccination.[378] This has led to governments and private organizations around the world introducing measures to incentivize or coerce vaccination, such as lotteries,[379] mandates,[380] and free entry to events,[381] which has in turn led to further misinformation about the legality and effect of these measures themselves.[382]

In the US, some prominent biomedical scientists who publicly advocate vaccination have been attacked and threatened in emails and on social media by anti-vaccination activists.[383]The United States Department of Defense (DoD) undertook a disinformation campaign in the Philippines, later expanded to Central Asia and the Middle East, which sought to discredit China, in particular its Sinovac vaccine, disseminating hashtags of #ChinaIsTheVirus and posts claiming that the Sinovac vaccine contained gelatin from pork and therefore was haram or forbidden for purposes of Islamic law.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch

![Map showing share of population fully vaccinated against COVID-19 relative to a country's total population[note 1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/World_map_of_share_of_people_who_received_all_doses_prescribed_by_the_initial_COVID-19_vaccination_protocol.png/510px-World_map_of_share_of_people_who_received_all_doses_prescribed_by_the_initial_COVID-19_vaccination_protocol.png)