アルミニウス主義

この記事には独自研究が含まれているおそれがあります。 |

アルミニウス主義(アルミニウスしゅぎ)は17世紀初頭に始まったプロテスタント運動であり、オランダ改革派神学者ヤコブス・アルミニウスと、レモンストラント派として知られる彼の歴史的支持者の神学的考えに基づいている。オランダのアルミニウス主義は、ネーデルランド連邦共和国に提出された神学声明である「レモンストランス」(1610年)で最初に表明された。これは、予定説の解釈に関連するカルヴァン主義の教義を和らげる試みを表現したものであった。

アルミニウスが主な貢献者である古典的アルミニウス主義と、ジョン・ウェスレーが主な貢献者であるウェスレー派アルミニウス主義は、2つの主要な思想流派である。アルミニウス主義の中心となる信念は、再生を準備する神の先行する恵みは普遍的であり、再生と継続的な聖化を可能にする神の恵みは抵抗可能であるというものである。

多くのキリスト教教派、特に17世紀のバプテスト派、18世紀のメソジスト派、20世紀のペンテコステ派はアルミニウス派の見解の影響を受けている。

歴史

[編集]先駆的な運動と神学的な影響

[編集]

アルミニウスの信仰、すなわちアルミニウス主義は、彼から始まったわけではない[1]。宗教改革以前には、ワルドー派などのグループも同様に、予定説よりも個人の自由を主張していた[2]。 再洗礼派の神学者バルタザール・フブマイヤー(1480-1528)も、アルミニウスよりほぼ1世紀前に、アルミニウスとほぼ同じ見解を唱えていた[1]。アルミニウス主義と再洗礼派の救済論は、ほぼ同等である[3][4]。特に、メノナイト派は、アルミニウス主義の観点を明確に支持するかどうかにかかわらず、歴史的にアルミニウス主義者であり、カルヴァン主義の 救済論を拒否した[5]。再洗礼派の神学は、ヤコブス・アルミニウスに影響を与えたと思われる[3]。少なくとも、彼は「再洗礼派の観点に共感的で、彼の説教には再洗礼派がよく出席していた」[4]。同様に、アルミニウスは、デンマークの ルター派神学者ニールス・ヘミングセン(1513–1600)が彼と同じ救済論の基本的な見解を持っていたと述べており、ヘミングセンの影響を受けた可能性がある[6]。もう一人の重要人物であるセバスチャン・カステリオン(英語版)(1515–1563)は、カルヴァンの予定説と宗教的不寛容に関する見解に反対し、メノナイト派とアルミニウスの周囲の特定の神学者に影響を与えたことが知られている[7]。アルミニウス派の初期の批評家は、カステリオンをアルミニウス派運動の背後にある主な思想家として挙げた[8]。

アルミニウス主義の出現

[編集]

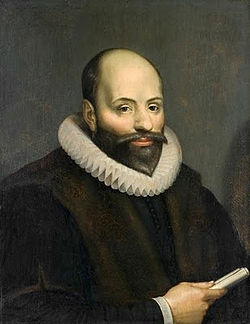

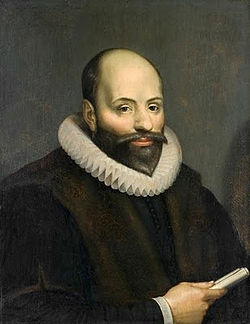

ヤコブス・アルミニウス(1560-1609)はオランダの牧師、神学者であった[9]。彼はカルヴァンの後継者として選ばれたテオドール・ベザに教えを受けたが、聖書を調べた結果、神は無条件に救済のためにある者を選ぶという師の神学を否定した[9]。その代わりにアルミニウスは、神の選びは信者からであり、それによって信仰が条件となると提唱した。アルミニウスの見解はオランダのカルヴァン主義者、特にフランシスカス・ゴマルスによって異議を唱えられた[10]。

アルミニウスは、ハーグでネーデルランド連邦共和国の判事たちに自身の神学を『意見表明』 (1608年)で示した[11]。彼の死後、アルミニウスの信奉者たちは彼の神学的ビジョンを推し進め、ベルギー信仰告白の厳格なカルヴァン主義との相違点を表明した『五箇条の抗議』(1610年)を作成した[10]。こうしてアルミニウスの信奉者たちはレモンストラント派と呼ばれ、 1611年の対抗抗議の後、ゴマルスの信奉者たちは反レモンストラント派と呼ばれた[12]。

政治的駆け引きの末、オランダのカルヴァン派はモーリス1世を説得して事態に対処させた[9]。モーリスはアルミニウス派の政務官を組織的に解任し、ドルドレヒトで全国会議を招集した。このドルト会議は主にオランダのカルヴァン派(102人)によって開かれ、アルミニウス派は除外され(13人が投票禁止)、他国のカルヴァン派代表(28人)が参加し、1618年にアルミニウスとその追随者を異端者として非難する文書を発表した。ドルト信仰基準書は、他のトピックの中でも特にアルミニウス派の教義に反応し、後にカルヴァン主義の五原則として明確にされることを予期していた[10]。

オランダ全土のアルミニウス派は職務を解かれ、投獄され、追放され、沈黙を誓わされた。12年後、オランダは公式にアルミニウス主義を宗教として保護したが、アルミニウス派とカルヴァン派の間の敵意は続いた[9]。初期のレモンストラント派のほとんどはアルミニウス主義の古典的なバージョンに従っていた。しかし、フィリップ・ファン・リンボルフなど、彼らの中には半ペラギウス主義や合理主義の方向に進んだ者もいた[13]。

英国国教会におけるアルミニウス主義

[編集]

イングランドでは、アルミニウス主義と呼ばれる教義[14]は、実質的にはアルミニウスの教義より以前から、またそれと並行して信じられていた[15]。39箇条の宗教条項(1571年に完成)は、アルミニウス主義とカルヴァン主義のどちらの解釈とも両立できるほど曖昧であった[15]。イングランド国教会におけるアルミニウス主義は、基本的にカルヴァン主義の否定の表現であり、一部の神学者だけが古典的なアルミニウス主義を支持し、残りは半ペラギウス派かペラギウス派であった[9][15][16]。この特定の文脈では、現代の歴史家は、一般的に古典的なアルミニウス主義に従わなかった神学者の傾向を指すのに、「アルミニウス主義者」よりも「プロトアルミニウス主義者」という用語を好んで使用している[17]。イギリスのアルミニウス主義は、ジョン・グッドウィンのようなアルミニウス派ピューリタンや、ジェレミー・テイラーやヘンリー・ハモンドのような高位聖公会アルミニウス派によって代表された[15]。ウィリアム・ロードのような17世紀の聖公会アルミニウス派は、カルヴァン派ピューリタンと戦った[15]。彼らは実際にアルミニウス主義を国教会の観点から見ていたが、これはアルミニウスの見解とは異質な考えだった[9]。この立場は、イングランド王チャールズ1世の治世(1625-1649年)下で特に顕著になった[15]。イングランド内戦(1642-1651年)の後、長老派を容認したイングランド王チャールズ2世は、イングランド国教会にアルミニウス主義の思想を復活させた[18]。王政復古(1660年)後も、アルミニウス主義は50年ほど支配的だった[19]。

バプテスト

[編集]バプテスト運動は17世紀にイギリスで始まった。最初のバプテスト派は「一般」あるいは無制限の贖罪を告白していたことから「一般バプテスト派」と呼ばれたアルミニウス派であった[20]。バプテスト運動はトーマス・ヘルウィスが始めたもので、彼は師匠のジョン・スミス(アムステルダムのオランダ・ウォーターランダー・メノナイト派の共通の信仰やその他の特徴に移行していた)のもとを離れ、ロンドンに戻って1611年にイギリス初のバプテスト教会を設立した。その後の一般バプテスト派のジョン・グリフィス、サミュエル・ラヴデイ、トーマス・グランサムらはアルミニウスのアルミニウス主義を反映した改革派アルミニウス派神学を擁護した。一般バプテスト派は、アルミニウス派の見解を数多くの信仰告白にまとめたが、最も影響力があったのは1660年の標準信仰告白(the Standard Confession)である。 1640年代には、アルミニウス派の教義から離れ、長老派と独立派の強力なカルヴァン主義を受け入れた特定バプテスト派が結成された。彼らの強力なカルヴァン主義は、1644年のロンドン・バプテスト信仰告白や1689年の第2ロンドン信仰告白などの信仰告白で宣伝された。1689年のロンドン信仰告白は後にアメリカのカルヴァン派バプテスト派(フィラデルフィア・バプテスト信仰告白と呼ばれる)によって使用され、1660年の標準信仰告白は、すぐにフリー・ウィル・バプテストとして知られるようになったイギリス一般バプテスト派のアメリカ人後継者によって使用された[21]。

メソジスト

[編集]

1770年代初頭、英国国教会の牧師ジョン・ウェスレーとジョージ・ホワイトフィールドが関与したメソジストとカルヴァン主義の論争において、ウェスレーは半ペラギウス主義という非難に対してアルミニウス主義者としてのアイデンティティを受け入れることで応えた[22]。ウェスレーはアルミニウスの信条に精通していたわけではなく、アルミニウスの教えに直接依存することなく主に自分の見解を形成した[23]。ウェスレーは17世紀イギリスのアルミニウス主義と一部のレモンストラント派の代弁者から顕著な影響を受けた[24]。しかし、彼はアルミニウスの信条の忠実な代表者として認められている[25]。ウェスレーは『アルミニウス主義者』 (1778年)という定期刊行物や『冷静に考察した予定説』などの記事を通じて自らの救済論を擁護した[26]。彼は自らの立場を支持するために、全的堕落に対する信仰を強く主張しつつ、先行恩寵などの他の教義を明らかにした[27][28]。同時に、ウェスレーはカルヴァン主義の予定説の特徴であると主張する決定論を攻撃した[29]。彼は典型的にはキリスト教的完全性(「罪のなさ」ではなく、完全に成熟した状態)という概念を説いた[9]。彼の思想体系はウェスレー派アルミニウス主義として知られるようになり、その基礎は彼と同僚の説教者ジョン・ウィリアム・フレッチャーによって築かれた[30][31]。メソジストもまた、救済と人間の行為に関する独自の神学上の複雑さを乗り越えた[32][33]。 1830年代の第二次大覚醒の時期に、ペラギウス派の影響の痕跡がアメリカのホーリネス運動に表面化した。その結果、ウェスレー神学の批評家たちは、その広範な思想を不当に認識したり、不当なレッテルを貼ったりしてきた[34]。しかし、その中核はアルミニウス主義であると認識されている[28][33]。

ペンテコステ派

[編集]ペンテコステ派は、チャールズ・パーハム(1873-1929)の活動にその背景がある。運動としての起源は、1906年にロサンゼルスで起こったアズサ通りの信仰復興運動(リバイバル)である。このリバイバルは、ウィリアム・J・シーモア(1870-1922)が主導した[35]。初期のペンテコステ派の説教者の多くがメソジスト派やホーリネス派の背景を持っていたため、ペンテコステ派の教会は通常、ウェスレー派のアルミニウス主義から生まれた実践を持っていた[36]。 20世紀の間に、ペンテコステ派の教会が落ち着き、より標準的な形式を取り入れ始めると、完全にアルミニウス主義的な神学を定式化し始めた[37]。今日、アッセンブリーズ・オブ・ゴッドなどのペンテコステ派の宗派は、抵抗可能な恵み、条件付きの選び、信者の条件付きの保障などのアルミニウス主義の見解を支持している[38][39][40]。

現在の状況

[編集]プロテスタント教派

[編集]

アルミニウス主義の支持者は多くのプロテスタント教派に根付いており[41]、時にはカルヴァン主義などの他の信仰が同じ教派内に存在する[42]。ルーテル派の神学的な伝統はアルミニウス主義と一定の類似点があり[43]、ルーテル派の教会の中にはアルミニウス主義を受け入れているところもあるかもしれない[44]。新しい福音主義の英国国教会の教派もアルミニウス主義神学に対してある程度の開放性を示している[44]。 メノナイト派、フッター派、アーミッシュ、シュヴァルツェナウ兄弟会などのアナバプテスト派の教派はアナバプテスト神学を信奉しており、これは「いくつかの点で」アルミニウス主義に似た救済論を唱えている[45][46][44]。アルミニウス主義は一般バプテスト派の中に見られ[46]、これには自由意志バプテスト派として知られる一般バプテスト派の支流教派が含まれる[47]。南部バプテスト派の大多数は、永遠の安全を信じる伝統的な形態のアルミニウス主義を受け入れているが[48][49][50][44]、カルヴァン主義が受け入れられつつあると考える人も多く存在する[51]。アルミニウス主義の支持者の中には、キリスト教会やキリスト教会の復興運動の中にいる人もいる[47]。さらに、セブンスデー・アドベンチスト教会にもアルミニウス主義が見られる[44]。アルミニウス主義(特にウェスレー派アルミニウス主義神学)はメソジスト教会で教えられており[52]、これには福音派メソジスト教会、ナザレン教会、自由メソジスト教会、ウェスレー派教会[47]、救世軍などホーリネス運動に賛同する教派も含まれる[53]。また、ペンテコステ派を含む一部のカリスマ派も含まれる[47][54][46][55]。

学術的支援

[編集]アルミニウス派神学は、様々な歴史的時代や神学界にわたる神学者、聖書学者、弁証家から支持を得ている。注目すべき歴史上の人物としては、ヤコブス・アルミニウス[56]、シモン・エピスコピウス[13]、フーゴー・グロティウス[13]、 ジョン・グッドウィン[57]、トーマス・グランサム[58]、ジョン・ウェスレー[59]、リチャード・ワトソン[60]、トーマス・オズモンド・サマーズ[60]、ジョン・マイリー[61]、ウィリアム・バート・ポープ[60]、ヘンリー・オートン・ワイリー[62]などがあげられる。

現代のバプテスト派の伝統では、アルミニウス派神学の支持者としてロジャー・E・オルソン[63]、F・リロイ・フォーリンズ[64]、ロバート・ピシリリ[65]、J・マシュー・ピンソン[66]などがいる。メソジスト派の伝統では、トーマス・オデン[64]、ベン・ウィザリントン3世[67]、デイビッド・ポーソン[68]、BJ・オロペザ[69]、トーマス・H・マッコール[63]、フレッド・サンダース[70]などが著名な支持者です。ホーリネス運動にはカール・O・バングス[71]やJ・ケネス・グリダーのような神学者がいる[66]。さらに、キース・D・スタングリン[63]、クレイグ・S・キーナー[72]、グラント・R・オズボーン[73]などの学者もアルミニウス派の見解を支持している。

神学

[編集]神学の遺産

[編集]

ペラギウス-アウグスティヌス主義の枠組みは、アルミニウス主義の神学的、歴史的遺産を理解するための重要なパラダイムとして役立つ可能性がある[74]。アウグスティヌス(354–430)以前は、救いの協同的見解がほぼ普遍的に支持されていた[75]。しかし、ペラギウス(354年頃–418)は、人間は自分の意志で神に完全に従うことができると主張した[76]。そのため、ペラギウス主義の見解は「人間主義的モナージズム(英語版)」と呼ばれている[77][78]。この見解は、カルタゴ教会会議(418)とエフェソス公会議(431)で非難された[79]。これに対して、アウグスティヌスは、神がすべての人間の行動の究極の原因であるという見解を提唱したが、これはソフトな決定論と一致する立場である[80]。そのため、アウグスティヌス主義の見解は「神的モナージズム」と呼ばれている[81]。しかし、アウグスティヌスの救済論は二重の予定説を暗示しており[82]、これはアルル教会会議(475)で非難された[83]。

この時期に、ペラギウス主義の穏健な形態が現れ、後に半ペラギウス主義と呼ばれるようになった。この見解は、人間の意志が救済を開始するものであり、神の恩寵ではないと主張した[84]。そのため、半ペラギウス主義の見解は「人間が開始した協働主義」と表現される[85]。529年、第二オラニエ会議は半ペラギウス主義を取り上げ、信仰の始まりさえも神の恩寵の結果であると宣言した[86][87][88]。これは、人間の信仰を可能にする先行する恩寵の役割を強調している[89][90]。そのため、しばしば「セミアウグスティヌス派」と呼ばれるこの見解は「神が開始した協働主義」と表現される[91][92][93][94]。また、教会会議は悪への予定説を否定した[95]。アルミニウス主義はこの見解の主要な側面と一致しているため[91]、初期教会の神学的なコンセンサスへの回帰であると見る人もいる[96]。さらに、アルミニウス主義はカルヴァン主義の救済論的多様化と見ることもでき[97]、より具体的には、カルヴァン主義と半ペラギウス主義の神学的な中間地点と見なすことができる[98]。

アルミニウス派神学は、一般的に2つの主要な変種に分けられる。ヤコブス・アルミニウスの教えに基づく古典的アルミニウス主義と、主にジョン・ウェスレーによって形成された密接に関連した変種であるウェスレー派アルミニウス主義である[99]。

古典的アルミニウス主義

[編集]定義と用語

[編集]

古典的アルミニウス主義はプロテスタントの神学的な見解であり、神の再生のための先行する恵みは普遍的であり、再生と継続的な聖化を可能にする恵みは抵抗可能であると主張する[100][101][102]。この神学体系はヤコブス・アルミニウスによって提唱され、シモン・エピスコピウス[103]やヒューゴ・グロティウスなどの一部のレモンストラント派によって維持された[104]。

アルミニウス派神学は契約神学の言語と枠組みを取り入れている[105][106]。その中核となる教えは、アルミニウスの見解を反映した五箇条の抗議にまとめられており、いくつかの部分は彼の意見表明から直接引用されている[107]。一部の神学者は、この体系を「古典的アルミニウス主義」と呼んでいる[108][109]。他の神学者は、「宗教改革アルミニウス主義」[110]または「改革派アルミニウス主義」[111]を好む。なぜなら、アルミニウスは信仰のみ、恵みのみといった宗教改革の原則を支持していたからである[112]。

神の摂理と人間の自由意志

[編集]アルミニウス主義は、神は遍在し、全能であり、全知であるとする古典的な有神論を受け入れている[113]。その見解では、神の力、知識、存在には、神の神性と性格の外には外的な制限がない。

さらに、アルミニウス主義の神の主権に関する見解は、神の性格から生じる公理に基づいている。第一に、神の選びは、神がいかなる場合でも、また二次的にも、悪の創造者ではないというように定義されなければならない。それは、特にイエス・キリストにおいて完全に明らかにされた神の性格とは一致しない[114][115]。一方、悪に対する人間の責任は保持されなければならない[116]。これら2つの公理は、神が被造物と交流する際に、その主権を明示するために選択した特定の方法を必要とする。

一方で、それは神が限られた摂理の様式に従って行動することを要求する。これは、神がすべての出来事を決定することなく意図的に主権を行使することを意味する。他方では、それは神の選びが「予知による予定」であることを要求する[117]。したがって、神の予知は徹底的かつ完全であり、神の確実性と人間の行動の自由が一致する[118]。

自由意志に関する哲学的見解

[編集]アルミニウス主義は古典的な自由意志論と足並みを揃え、非両立主義の立場をとっている。道徳的責任に不可欠な自由意志は、決定論とは本質的に両立しないと主張する[119]。アルミニウス主義神学では、人間は自由意志を持ち、選択の究極の源泉となり、他の選択をする能力も与えられる[120]。この哲学的枠組みは神の摂理の概念を支持し、神が創造物に影響を与え、監督することを認めている[121]。しかし、人間の行動に対する神の絶対的な支配という考えは、そのような支配が人間の責任を伴わない限り認められている[122][123]。

自由意志に関する精神的な見解

[編集]アルミニウス主義は、神の恩寵の助けがなければ、人間の自由意志は霊的な善を選ぶことができないとしている[124][125]。したがって、人間は完全な堕落の状態にあり、堕落した霊的性質を持っている[126]。アルミニウスは、人類の代表であるアダムが神に対して罪を犯したため、すべての人がこの堕落した状態で生まれると信じていた可能性が高い。この見解は、後にいくつかの著名なアルミニウス主義者によって共有された[127]。アウグスティヌス、ルター、カルヴァンと同様に、アルミニウスは、人間の自由意志が霊的に「捕らわれ」、「奴隷化」されていることに同意した[128][129]。しかし、先行恩寵の作用により、人間の自由意志は「解放」されることができる[130]。つまり、霊的な善を選ぶ能力、特に神の救済への呼びかけを受け入れる能力を回復することができる[131]。

贖罪の範囲と性質

[編集]贖罪は普遍的に意図されている。イエスの死はすべての人々のためであり、イエスはすべての人々を自らに引き寄せ、信仰を通して救済の機会を与える[132]。

イエスの死は神の正義を満たす:選ばれた人々の罪に対する罰は、キリストの磔刑によって完全に支払われる。したがって、キリストの死はすべての罪を償うが、それが実現するには信仰が必要である。アルミニウスは、「裁判官の行為として使われる義認は、純粋に慈悲を通して義を帰することである[...] または、いかなる赦しもなしに、正義の厳格さに従って、人が神の前で義とされることである[...]」と述べている[133]。したがって、義認は、慈悲を通して義を帰すことによって見られる[134]。厳密に定義されていないが、この見解は、キリストの義は信者に帰属することを示唆し、キリストとの結合(信仰を条件とする)がキリストの義を信者に移すことを強調している[135][136]。

キリストの贖罪は、選ばれた者だけに限定された代償的効力を持つ。アルミニウスは、神の正義は刑罰の代償によって満たされると主張した[137]。ヒューゴ・グロティウスは、それは政府によって満たされると教えた[138]。歴史上および現代のアルミニウス主義者は、これらの見解の1つを支持してきた[139]。

人間の再生

[編集]アルミニウス主義では、神はすべての人に恵み(一般的には先行の恵みと呼ばれる)を与えることによって救いの過程を開始する。この恵みは各個人の中で働き、彼らを福音へと導き、誠実な信仰を可能にし、再生へと導く[140]。それは、個人が自由に受け入れたり拒否したりできるように、動的な影響と反応の関係を通じて機能する[141][130]。したがって、回心は「神が開始した相乗効果」として説明される[91]。

人間の選び

[編集]選びは条件付きである。アルミニウスは選びを「神ご自身が永遠の昔から、キリストにおいて信者を義と認め、永遠の命に受け入れることを定められた神の定め」と定義した[142]。誰が救われるかを決めるのは神のみであり、信仰を通してイエスを信じる者は皆義とされるというのが神の定めである。アルミニウスによれば、「神は、信仰によってキリストに接ぎ木されない限り、誰もキリストに属さない」のである[142]。

神は選ばれた者たちに栄光ある未来を予定する。予定とは、誰が信じるかを予定することではなく、信者の将来の相続財産を予定することである。したがって、選ばれた者たちは、養子縁組、栄光、そして永遠の命を通して神の子となるよう予定されている[143]。

人類の保存

[編集]終末論的な考察に関連して、ヤコブス・アルミニウス[144]とシモン・エピスコピウス[145]を含む最初のレモンストラント派は、審判の日に神によって悪人が投げ込まれる永遠の火を信じていた。

条件付き保護: すべての信者は、キリストに留まるという条件で、完全な救済の保証を受ける。救済は信仰に条件付けられているため、忍耐も条件付きである[146]。アルミニウスは、聖書は信者がキリストと聖霊による恵みによって「サタン、罪、世界、そして自分自身の肉と戦い、これらの敵に勝利する」力を与えられていると教えていると信じていた[147]。さらに、キリストと聖霊は常に存在し、さまざまな誘惑を通して信者を助け、支援する。しかし、この保護は無条件ではなく条件付きである。「彼ら[信者]が戦いに備えて立ち、彼の助けを懇願し、自分自身に不足がない限り、キリストは彼らを倒れないように保護する。」[148][149]

背教の可能性

[編集]アルミニウスは棄教の可能性を信じていた。しかし、彼がこの問題について執筆していた期間を通して[150]、彼は読者の信仰を考慮して、時にはより慎重に表現した[151][152]。 1599年、彼はこの問題にはもっと聖書的な考察が必要だと述べた[153]。アルミニウスは「意見表明」(1607年)で、「私は真の信者が信仰から完全に、あるいは最終的に離れ、滅びることがあるなどとは決して教えなかった。しかし、私にはこの様相を帯びているように思える聖書の一節があることを私は隠さない。」と述べた[154]。

しかし、アルミニウスは他の箇所では、堕落の可能性について確信を表明している。1602年頃、彼は教会に統合された人が神の働きに抵抗する可能性があり、信者の安全は信仰を捨てないという選択にのみかかっていると述べた[155][156]。彼は、神の契約は堕落の可能性を排除するものではなく、恐怖という賜物を与え、それが人々の心の中で繁栄している限り、個人が脱走しないようにするものだと主張した[157]。そして、ダビデが罪を犯して死んでいたら、彼は失われていただろうと教えた[158][135]。 1602年にアルミニウスはまた、「キリストの信者は怠惰になり、罪に道を譲り、徐々に完全に死に、信者でなくなる可能性がある」と書いた[159]。

アルミニウスにとって、ある種の罪、特に悪意から生じた罪は信者を堕落させる原因となる[135][160]。 1605年にアルミニウスは次のように書いている。「しかし、ダビデに見られるように、信者が大罪に陥る可能性はある。したがって、死んだら罪に問われるであろうその瞬間に、信者は堕落する可能性がある」[161]。学者たちは、アルミニウスが棄教への2つの道を明確に特定していると指摘している。1.「拒絶」、または2.「悪意のある罪を犯す」[162][135]。彼は、厳密に言えば、信者は直接信仰を失うことはないが、信じることをやめ、堕落することはあると示唆した[163][152][164]。

1609年にアルミニウスが死去した後、彼の信奉者たちは、棄教の可能性について慎重な姿勢を示した彼の意見表明(1607年)を文字通りに根拠とする「抗議文」 (1610年)を書いた[162]。特に、その第5条では、棄教の可能性についてさらに研究する必要があると述べられている[165]。 1610年からドルト会議(1618年)の公式議事進行までの間に、レモンストラント派は、真の信者でも信仰を捨てて不信者として永遠に滅びる可能性があると聖書が教えていると確信するようになった[166]。彼らはその見解を「レモンストラント派の意見」(1618年)で公式化し、それがドルト会議中の彼らの公式見解となった[167]。彼らは後に、同じ見解をレモンストラント信仰告白(1621年)で表明した[168]。

棄教の許し

[編集]アルミニウスは、棄教が「悪意のある」罪から生じたものであれば許されると主張した[135][169]。棄教が「拒絶」から生じたものであれば許されない[170]。アルミニウスに続いて、レモンストラント派は、棄教は可能ではあっても、一般的には回復不可能ではないと信じた[171]。しかし、自由意志バプテスト派を含む他の古典的なアルミニウス派は、棄教は回復不可能であると教えている[172][173]。

ウェスレー派アルミニウス主義

[編集]特徴的な側面

[編集]ジョン・ウェスレーはアルミニウス自身が教えたことの大部分に全面的に同意した[25]。ウェスレー派アルミニウス主義は古典的なアルミニウス主義とウェスレー派完全主義が融合したものである[174][175][9]。

償いの性質

[編集]ウェスレーの贖罪観は、刑罰的代償と統治的理論(英語版)の混合として理解されるか[176]、または刑罰的代償のみとして見なされる[177][178][179]。歴史的に、ウェスレー派アルミニウス主義者は、刑罰的または統治的贖罪理論のいずれかを採用した[139]。

義化と聖化

[編集]ウェスレー派の神学では、義化は、本質的に義とされることではなく、罪の赦しとして理解されている。義は、人生における神聖さの追求を伴う聖化を通じて達成される[180]。ウェスレーは、信仰を通して信者に与えられる義を指す「帰属される義」は、信者の生活の中でこの義が明らかになる「与えられた義」に変わらなければならないと教えた[181]。

キリスト教の完全性

[編集]ウェスレーは、聖霊を通してキリスト教徒は、自発的な罪がないことを特徴とする実質的な完全性、つまり「完全な聖化」の状態に到達できると教えた[182]。この状態には、神と隣人への愛を体現することが含まれる[183]。これは、すべての間違いや誘惑から解放されることを意味するのではなく、完成したキリスト教徒は依然として赦しを求め、聖性を求める必要がある。結局のところ、この文脈における完全性とは愛に関するものであり、絶対的な完全性ではない[184]。

人間の保存と背教

[編集]ウェスレーは、真のキリスト教徒が棄教する可能性があると信じていた。彼は、罪だけではこの喪失につながるのではなく、長期間告白されていない罪と意図的な棄教が、永遠の恵みからの堕落につながる可能性があることを強調した[185]。しかし、彼はそのような棄教は回復不可能なものではないと信じていた[186]。

アルミニウス主義と他の見解

[編集]ペラギウス主義との相違

[編集]ペラギウス主義は原罪と全的堕落を否定する教義である。アルミニウスやウェスレーに基づくアルミニウス主義の体系はどれも原罪や全的堕落を否定していない[187]。アルミニウスとウェスレーはどちらも、人間の基本的な状態は、正義を貫くことも、神を理解することも、神を求めることもできない状態であると強く主張した[188]。アルミニウスはペラギウス主義を「大いなる虚偽」と呼び、「[その神学の]帰結を心から嫌悪していると告白しなければならない」と述べた[189]。この関連性はアルミニウスやウェスレーの教義に帰せられると名誉毀損とみなされ[190]、アルミニウス主義者はペラギウス主義に対するあらゆる非難を否定する[191][192]。

半ペラギウス主義との相違

[編集]半ペラギウス主義は、信仰は人間の意志から始まり、その継続と成就は神の恩寵に依存すると考え[84]、それを「人為的協働主義」と呼んでいる[85]。対照的に、古典的アルミニウス主義とウェスレー派アルミニウス主義はどちらも、神からの先行する恩寵が救済のプロセスを開始すると主張しており[193][194]、この見解は「セミアウグスティヌス派」または「神為的協働主義」と呼ばれることもある[91][92]。宗教改革後、改革派神学者は「人為的協働主義」と「神為的協働主義」の両方を「セミペラギウス主義」として分類することが多く[195]、アルミニウス主義が半セミペラギウス主義と一致しているという誤った信念につながることがよくある[196][197]。

カルヴァン主義との相違

[編集]カルヴァン主義とアルミニウス主義は、歴史的ルーツや多くの神学的教義を共有しているが、神の予定と選びの概念に関しては大きく異なっている。これらの違いを根本的なものと捉える人もいるが、キリスト教神学の広い範囲の中では比較的小さな違いだと考える人もいる[198]。

類似点

[編集]人間の精神的状態 – アルミニウス派は全的堕落の教義についてはカルヴァン派と同意しているが、神がこの人間の状態をどのように改善するかについての理解は異なっている[199]。

違い

[編集]選びの性質 – アルミニウス派は最終的な救いへの選びは信仰に条件付けられていると信じているが[200]、カルヴァン派は無条件の選びは神の予定論に基づいており[201]、神が人間の信仰を含むすべてのものの究極の原因であると考えている[202]。 恵みの性質 – アルミニウス派は、神が先行する恵みを通じて、個人の選択する霊的能力を普遍的に回復し、それに続く義認の恵みは抵抗できないと信じている[203]。しかし、カルヴァン派は、神の有効な召命は選ばれた者にのみ与えられ、それに続く恵みは抵抗できないと主張する[204]。 贖罪の範囲 – アルミニウス派は、四原則カルヴァン派とともに、贖罪は選ばれた者に限定されるというカルヴァン派の教義に反して、普遍的な贖罪を主張している[205]。超カルヴァン派を除く両派は、福音の招きは普遍的なものであり、区別なくすべての人に与えられるべきだと信じている[206]。 信仰の堅持 – アルミニウス派は、最終的な救済への維持は信仰に条件付けられており、背教によって失われる可能性があると信じている。彼らは、あらゆる外的力からのキリストの保護に頼り、キリストにおける現在の安全を主張する[146]。一方、カルヴァン派は聖徒の堅持を主張し、選ばれた者は人生の最後まで信仰を堅持すると主張する[207]。しかし、信者は最後まで自分が選ばれた者かどうかを確実に知ることはできない[208]。このため、カルヴァン派内で最終的な救済の保証に関する解釈は異なっている[209][210]。

オープン神学との相違

[編集]オープン神学の教義は、神は遍在、全能、全知であるとしているが、未来の性質については異なる。オープン神学の信者は、人々がまだ自由な決定を下していないため、未来は完全には決定されていない(または「確定」していない)と主張する。したがって、神は未来を、完全な確実性(神によって決定された出来事)ではなく、部分的に可能性(人間の自由な行動)で知っている[211]。アルミニウス主義者の中には、オープン神学を伝統的なアルミニウス主義の歪曲と見なし、拒否する者もいる[212]。彼らは、オープン神学が古典的なアルミニウス主義からプロセス神学へと移行していると信じている[213]。他の人は、アルミニウス主義の教義と一致していないにもかかわらず、キリスト教内の有効な代替観点と見なしている[214]。

脚注

[編集]出典

[編集]- ^ a b Olson 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 147.

- ^ a b Sutton 2012, p. 86.

- ^ a b Bangs 1985, p. 170.

- ^ Bender 1953: 「メノナイト派は、明確にアルミニウス派の見解を支持していたかどうかに関わらず、歴史的にアルミニウス派の神学を信奉してきた。スイス・南ドイツ派でもオランダ・北ドイツ派でも、カルヴァン主義を受け入れたことはなかった。また、どの国でも、メノナイト派の信仰告白はカルヴァン主義の 5 つの原則を教えることはなかった。しかし、20世紀、特に北米では、一部のメノナイト派が、特定の聖書学校やこの運動とその学校が作成した文献の影響を受けて、カルヴァン主義の聖徒の堅忍または「一度恩寵を受けたら、永遠に恩寵を受ける」という教義を採用しました。そうすることで、彼らはアナバプテスト・メノナイト運動の歴史的なアルミニウス派から逸脱した。」

- ^ Olson 2013b: "I am using 'Arminianism' as a handy [...] synonym for 'evangelical synergism' (a term I borrow from Donald Bloesch). [...] It's simply a Protestant perspective on salvation, God's role and ours, that is similar to, if not identical with, what was assumed by the Greek church fathers and taught by Hubmaier, Menno Simons, and even Philipp Melanchthon (after Luther died). It was also taught by Danish Lutheran theologian Niels Hemmingsen (d. 1600)—independently of Arminius. (Arminius mentions Hemmingsen as holding the basic view of soteriology he held and he may have been influenced by Hemmingsen.)"

- ^ Guggisberg & Gordon 2017, p. 242.

- ^ Guggisberg & Gordon 2017, p. 242-244.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Heron 1999, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Wynkoop 1967, ch. 3.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2021, p. 29.

- ^ Loughlin 1907.

- ^ a b c Olson 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Tyacke 1990, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f McClintock & Strong 1880.

- ^ Tyacke 1990, p. 245: 「当時の宗教の変化の方向性を表すために使用できるさまざまな用語のうち、アルミニウス派は最も誤解を招きにくい用語である。これは、オランダの神学者ヤコブス・アルミニウスが通常そのように名付けられた思想の源泉であったという意味ではない。むしろ、アルミニウス派は、17世紀初頭のヨーロッパのさまざまな地域で勢力を伸ばしつつあった反カルヴァン主義の宗教思想の一貫した体系を示しているのである」

- ^ MacCulloch 1990, p. 94: "If we use the label 'Arminian' for English Churchmen, it must be with these important qualification in mind [of been related to the theology of Arminius]; 'proto-Arminian' would be a more accurate term."

- ^ Delumeau, Wanegffelen & Cottret 2012, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Wallace 2011, p. 233: 「エドワーズによれば、非カルヴァン主義的な見解が英国国教会の聖職者の間で多く採用されるようになったのは王政復古後のことである。カルヴァン主義を拒否した人々の中で先頭に立っていたのはアルミニウス派であり、エドワーズは、アルミニウス主義と戦い、英国国教会におけるアルミニウス主義の勝利に注目を集める非国教徒の方が多かった時代に、アルミニウス主義に対するカルヴァン主義の擁護者として登場した。」

- ^ Gonzalez 2014, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Torbet 1963, pp. 37, 145, 507.

- ^ Gunter 2007, p. 78.

- ^ Gunter 2007, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Keefer 1987, p. 89: 「ウェスレーがアルミニウスについて知っていたことは、2 つの基本的な情報源から得たものでした。まず、彼はレモンストラント派の代弁者を通じてアルミニウスについて知っていました。[...] ウェスレーのアルミニウス神学の 2 番目の情報源は、英国教会全般、特に 17 世紀の著述家たちでした。これが彼の圧倒的な情報源でした [...]」

- ^ a b Gunter 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Gunter 2007, p. 77.

- ^ Gunter 2007, p. 81.

- ^ a b Grider 1982, p. 55.

- ^ Grider 1982, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Knight 2018, p. 115.

- ^ Grider 1982, p. 56.

- ^ Grider 1982, pp. 53–55.

- ^ a b Bounds 2011, p. 50.

- ^ Bounds 2011, p. 50: "The American Holiness movement, influenced heavily by the revivalism of Charles Finney, inculcated some of his Soft Semi-Pelagian tendencies among their preachers and teachers [...]. This has provided critics of Wesleyan theology with fodder by which they pigeonhole inaccurately larger Wesleyan thought."

- ^ Knight 2010, p. 201.

- ^ Knight 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 93.

- ^ Studebaker 2008, p. 54. "Pentecostal theology, generally adopts an Arminian/Wesleyan structure of the ordos salutis [...]."

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2021, p. 240: "[T]he specifically Pentecostal denominations —such as the Assemblies of God, founded in 1914— have remained broadly Arminian when it comes to the matters of free, resistible grace and choice in salvation [...]."

- ^ AG 2017.

- ^ Olson 2014, pp. 2–3: "Methodism, in all its forms (including ones that do not bear that name), tends to be Arminian. (Calvinist Methodist churches once existed. They were founded by followers of Wesley's co-evangelist George Whitefield. But, so far as I am able to tell, they have all died out or merged with traditionally Reformed-Calvinist denominations.) Officially Arminian denominations include ones in the so-called 'Holiness' tradition (e.g., Church of the Nazarene) and in the Pentecostal tradition (e.g., Assemblies of God). Arminianism is also the common belief of Free Will Baptists (also known as General Baptists). Many Brethren [anabaptists-pietist] churches are Arminian as well. But one can find Arminians in many denominations that are not historically officially Arminian, such as many Baptist conventions/conferences."

- ^ Akin 1993: "In Protestant circles there are two major camps when it comes to predestination: Calvinism and Arminianism. Calvinism is common in Presbyterian, Reformed, and a few Baptist churches. Arminianism is common in Methodist, Pentecostal, and most Baptist churches."

- ^ Dorner 2004, p. 419: "Through its opposition to Predestinarianism, Arminianism possesses a certain similarity to the Lutheran doctrine, in the shape which the latter in the seventeenth century more and more assumed, but the similarity is rather a superficial one."

- ^ a b c d e Olson 2012.

- ^ Sutton 2012, p. 56: "Interestingly, Anabaptism and Arminianism are similar is some respects. Underwood wrote that the Anabaptist movement anticipated Arminius by about a century with respect to its reaction against Calvinism."

- ^ a b c Olson 2014, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d Olson 2009, p. 87.

- ^ SBC 2000, ch. 5.

- ^ Harmon 1984, pp. 17–18, 45–46.

- ^ Walls & Dongell 2004, pp. 12–13, 16–17.

- ^ Walls & Dongell 2004, pp. 7–20.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2021, p. 139.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2021, p. 241.

- ^ Akin 1993.

- ^ Gause 2007: "Pentecostals are almost universally Wesleyan-Arminian rather than Calvinist/Reformed, with rare exceptions among denominational Charismatic."

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 21.

- ^ More 1982, p. 1.

- ^ Pinson 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Olson 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Driscoll 2013, p. 299.

- ^ a b Olson 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Keathley 2014, p. 716.

- ^ a b Keathley 2014, p. 749.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2018, p. 118.

- ^ Stegall 2009, p. 485, n. 8.

- ^ Wilson 2017, p. 10, n. 30.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 125.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Marberry 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Osborne, Trueman & Hammett 2015, p. 134: "[...] Osborne Wesleyan-Arminian perspective".

- ^ Bounds 2011, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Schaff 1997, § 173. "In anthropology and soteriology [Lactantius] follows the synergism which, until Augustine, was almost universal."

- ^ Puchniak 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Barrett 2013, p. xxvii. "[H]umanistic monergism is the view of Pelagius and Pelagianism".

- ^ Peterson & Williams 2004, p. 36. "[T]he humanistic monergism of Pelagius."

- ^ Teselle 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Rogers 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Barrett 2013, p. xxvii, Template:Zwnj. "[D]ivine monergism is the view of Augustine and the Augustinians."

- ^ James 1998, p. 103. "If one asks, whether double predestination is a logical implication or development of Augustine's doctrine, the answer must be in the affirmative."

- ^ Levering 2011, p. 37.

- ^ a b Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b Barrett 2013, p. xxvii, Template:ZwnjTemplate:Zwnj. "[H]uman-initiated synergism is the view of Semi-Pelagianism".

- ^ Denzinger 1954, ch. Second Council of Orange, art. 5-7.

- ^ Pickar 1981, p. 797.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 701.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Bounds 2011, pp. 39–43.

- ^ a b Barrett 2013, p. xxvii, Template:ZwnjTemplate:ZwnjTemplate:Zwnj. "God-initiated synergism is the view of the Semi-Augustinians".

- ^ Oakley 1988, p. 64.

- ^ Thorsen 2007, ch. 20.3.4.

- ^ Denzinger 1954, ch. Second Council of Orange, art. 199. "We not only do not believe that some have been truly predestined to evil by divine power, but also with every execration we pronounce anathema upon those, if there are [any such], who wish to believe so great an evil."

- ^ Keathley 2014, p. 703, ch. 12.

- ^ Magnusson 1995, p. 62.

- ^ Olson 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Forlines 2001, p. xvii.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2021, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Olson 2009, pp. 16, 17, 200.

- ^ Wynkoop 1967, pp. 61–69.

- ^ Episcopius & Ellis 2005, p. 8: "Episcopius was singularly responsible for the survival of the Remonstrant movement after the Synod of Dort. We may rightly regard him as the theological founder of Arminianism, since he both developed and systematized ideas which Arminius was tentatively exploring before his death and then perpetuated that theology through founding the Remonstrant seminary and teaching the next generation of pastors and teachers."

- ^ Pinson 2002, p. 137.

- ^ Vickers 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Reasoner 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 190 "These points [of Remonstrance] are consistent with the views of Arminius; indeed, some come verbatim from his Declaration of Sentiments.

- ^ Forlines 2011.

- ^ Olson 2009.

- ^ Picirilli 2002, p. 1.

- ^ Pinson 2002, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Pinson 2003, pp. 135, 139.

- ^ Olson 2009, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Olson 2013a: "Basic to Arminianism is God's love. The fundamental conflict between Calvinism and Arminianism is not sovereignty but God's character. If Calvinism is true, God is the author of sin, evil, innocent suffering and hell. [...] Let me repeat. The most basic issue is not providence or predestination or the sovereignty of God. The most basic issue is God's character."

- ^ Olson 2014, p. 11.

- ^ Olson 2010: "Classical Arminianism does not say God never interferes with free will. It says God never foreordains or renders certain evil. [...] An Arminian could believe in divine dictation of Scripture and not do violence to his or her Arminian beliefs. [...] Arminianism is not in love with libertarian free will – as if that were central in and of itself. Classical Arminians have gone out of our way (beginning with Arminius himself) to make clear that our sole reasons for believe in free will as Arminians [...] are 1) to avoid making God the author of sin and evil, and 2) to make clear human responsibility for sin and evil."

- ^ Olson 2018: "What is Arminianism? A) Belief that God limits himself to give human beings free will to go against his perfect will so that God did not design or ordain sin and evil (or their consequences such as innocent suffering); B) Belief that, although sinners cannot achieve salvation on their own, without 'prevenient grace' (enabling grace), God makes salvation possible for all through Jesus Christ and offers free salvation to all through the gospel. 'A' is called 'limited providence,' 'B' is called 'predestination by foreknowledge.'"

- ^ Picirilli 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 149. "Classical free will theism is that form of this model found implicitly if not explicitly in the ancient Greek church fathers, most of the medieval Christian and theologians […] Classical free will theism describes free will as incompatible with determinism".

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Olson 2009, pp. 115–119.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 151. "Occasionally God suspends free will with a dramatic intervention that virtually forces a person to decide or act in some way".

- ^ Olson 2014, p. 8. "Arminianism includes no particular belief about whether or to what extent God manipulates the wills of men (human persons) with regard to bringing his plans (e.g., Scripture) to fruition.".

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 42–43, 59-.

- ^ Pinson 2002, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Olson 2009, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Grider 1994, ch. 10, "The Representative Theory".

- ^ Olson 2009, pp. 142–145.

- ^ Arminius 1853a, p. 526. "In this [fallen] state, the free will of man towards the true good is not only wounded, infirm, bent, and weakened; but it is also imprisoned, destroyed, and lost. And its powers are not only debilitated and useless unless they be assisted by grace, but it has no powers whatever except such as are excited by Divine grace."

- ^ a b Olson 2009, p. 142.

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 153.

- ^ Arminius 1853a, p. 316.

- ^ Arminius 1853c, p. 454.

- ^ Pinson 2002, p. 140. "Arminius allowed for only two possible ways in which the sinner might be justified: (1) by our absolute and perfect adherence to the law, or (2) purely by God's imputation of Christ's righteousness."

- ^ a b c d e Gann 2014.

- ^ Forlines 2011, p. 403. "On the condition of faith, we are placed in union with Christ. Based on that union, we receive His death and righteousness".

- ^ Pinson 2002, pp. 140 ff.

- ^ Picirilli 2002, p. 132.

- ^ a b Olson 2009, p. 224.

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 154 ff. "[I]ndeed this grace is so close to regeneration that it inevitably leads to Regeneration unless finally resisted."

- ^ Forlines 2001, pp. 313–321.

- ^ a b Arminius 1853c, p. 311.

- ^ Pawson 1996, pp. 109 ff.

- ^ Arminius 1853c, p. 376: "First, you say, and truly, that hell-fire is the punishment ordained for sin and the transgression of the law."

- ^ Episcopius & Ellis 2005, ch. 20, item 4.

- ^ a b Picirilli 2002, p. 203.

- ^ Arminius 1853b, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Arminius 1853b, pp. 465, 466: "This seems to fit with Arminius' other statements on the need for perseverance in faith. For example: 'God resolves to receive into favor those who repent and believe, and to save in Christ, on account of Christ, and through Christ, those who persevere [in faith], but to leave under sin and wrath those who are impenitent and unbelievers, and to condemn them as aliens from Christ'."

- ^ Arminius 1853c, pp. 412, 413: "[God] wills that they, who believe and persevere in faith, shall be saved, but that those, who are unbelieving and impenitent, shall remain under condemnation".

- ^ Stanglin & Muller 2009.

- ^ Cameron 1992, p. 226.

- ^ a b Grider 1982, pp. 55–56, Template:Zwnj. "Arminius used an ingenious device to teach [the possibility of Apostasy], so as not to seem to oppose Calvinism's eternal security doctrine head on and recklessly He admitted that believers cannot lose saving grace; but then he would add, quickly, that Christians can freely cease to believe, and that then they will lose saving grace. So, in a sense, believers cannot backslide; but Christians can cease to believe, and then, as unbelievers (but only as unbelievers), they lose their salvation"

- ^ Arminius 1853b, "A Dissertation on the True and Genuine Sense of the Seventh Chapter of the Epistle to the Romans", pp. 219–220, [1599]

- ^ Arminius 1853a, p. 665: "William Nichols notes: 'Arminius spoke nearly the same modest words when interrogated on this subject in the last Conference which he had with Gomarus [a Calvinist], before the states of Holland, on the 12th of Aug. 1609, only two months prior to his decease'".

- ^ Oropeza 2000, p. 16: "Although Arminius denied having taught final apostasy in his Declaration of Sentiments, in the Examination of the Treatise of Perkins on the Order and Mode of Predestination [c. 1602] he writes that 'a person who is being "built" into the church of Christ may resist the continuation of this process'. Concerning the believers, 'It may suffice to encourage them, if they know that no power or prudence can dislodge them from the rock, unless they of their own will forsake their position.'"

- ^ Arminius 1853c, p. 455, "Examination of the Treatise of Perkins on the Order and Mode of Predestination", [c. 1602]

- ^ Arminius 1853c, p. 458, "Examination of the Treatise of Perkins on the Order and Mode of Predestination", [c. 1602] "[The covenant of God (Jeremiah 23)] does not contain in itself an impossibility of defection from God, but a promise of the gift of fear, whereby they shall be hindered from going away from God so long as that shall flourish in their hearts."

- ^ Arminius 1853c, pp. 463–464, "Examination of the Treatise of Perkins on the Order and Mode of Predestination", [c. 1602]

- ^ Arminius 1853a, p. 667, Disputation 25, on Magistracy, [1602]

- ^ Stanglin 2007, p. 137.

- ^ Arminius 1853a, p. 388, Letter to Wtenbogaert, trans. as "Remarks on the Preceding Questions, and on those opposed to them", [1605]

- ^ a b Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 190.

- ^ Bangs 1960, p. 15.

- ^ Oropeza 2000, p. 16: "If there is any consistency in Arminius' position, he did not seem to deny the possibility of falling away".

- ^ Schaff 2007.

- ^ Picirilli 2002, p. 198. "Ever since that early period, then, when the issue was being examined again, Arminians have taught that those who are truly saved need to be warned against apostasy as a real and possible danger."

- ^ De Jong 1968, pp. 220 ff., art. 5, points 3–4: "True believers can fall from true faith and can fall into such sins as cannot be consistent with true and justifying faith; not only is it possible for this to happen, but it even happens frequently. True believers are able to fall through their own fault into shameful and atrocious deeds, to persevere and to die in them; and therefore finally to fall and to perish."

- ^ Witzki 2010.

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 174.

- ^ Stanglin 2007, p. 139.

- ^ De Jong 1968, pp. 220 ff., ch. 5.5: "Nevertheless, we do not believe that true believers, though they may sometimes fall into grave sins which are vexing to their consciences, immediately fall out of every hope of repentance; but we acknowledge that it can happen that God, according to the multitude of His mercies, may recall them through His grace to repentance; in fact, we believe that this happens not infrequently, although we cannot be persuaded that this will certainly and indubitably happen."

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 204 ff.

- ^ Pinson 2002, p. 159.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 189, note 20.

- ^ Sayer 2006, ch. "Wesleyan-Arminian theology": "Evangelical Wesleyan-Arminianism has as its center the merger of both Wesley's concept of holiness and Arminianism's emphasis on synergistic soteriology."

- ^ Pinson 2002, pp. 227 ff.: "Wesley does not place the substitionary element primarily within a legal framework [...]. Rather [his doctrine seeks] to bring into proper relationship the 'justice' between God's love for persons and God's hatred of sin [...] it is not the satisfaction of a legal demand for justice so much as it is an act of mediated reconciliation."

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 104–105, 132 ff.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 224: "Arminius did not believe [in the governmental theory of atonement], neither did Wesley nor some of his nineteenth-century followers. Nor do all contemporary Arminians."

- ^ Wood 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Elwell 2001, p. 1268. "[Wesley] states what justification is not. It is not being made actually just and righteous (that is sanctification). It is not being cleared of the accusations of Satan, nor of the law, nor even of God. We have sinned, so the accusation stands. Justification implies pardon, the forgiveness of sins. [...] Ultimately for the true Wesleyan salvation is completed by our return to original righteousness. This is done by the work of the Holy Spirit."

- ^ Oden 2012, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Wesley 1827, p. 66, "A Plain Account of Christian Perfection." "[Entire sanctification is] purity of intention."

- ^ Wesley 1827, p. 66, "A Plain Account of Christian Perfection."Template:Zwnj "[Entire sanctification is] loving God with all our heart, and our neighbor as ourselves."

- ^ Wesley 1827, p. 45, "Of Christian Perfection". "Even perfect holiness is acceptable to God only through Jesus Christ."

- ^ Pinson 2002, pp. 239–240. "the act of committing sin is not in itself ground for the loss of salvation [...] the loss of salvation is much more related to experiences that are profound and prolonged. Wesley sees two primary pathways that could result in a permanent fall from grace: unconfessed sin and the actual expression of apostasy."

- ^ Wesley & Emory 1835, p. 247, "A Call to Backsliders". "[N]ot one, or a hundred only, but I am persuaded, several thousands [...] innumerable are the instances [...] of those who had fallen but now stand upright."

- ^ Pinson 2002, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Arminius 1853b, p. 192.

- ^ Arminius 1853b, p. 219. The entire treatise occupies pp. 196–452

- ^ Pawson 1996, p. 106.

- ^ Pawson 1996, pp. 97–98, 106.

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 6 ff.

- ^ Schwartz & Bechtold 2015, p. 165.

- ^ Forlines 2011, pp. 20–24.

- ^ Marko 2020, p. 772. "Those who did not think a prevenient grace was necessary for initial human response or that it was resistible came to be called semi-Pelagians by Protestants in the post Reformation period."

- ^ Stanglin & McCall 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 30-31, 40-43, 79-81.

- ^ Gonzalez 2014, p. 180.

- ^ Olson 2009, pp. 31–34, 55–59.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Calvin 1845, 3.21.7: 「予定とは、神が各人に関して望むことをすべて自ら決定した永遠の定めを意味します。すべての人が平等に創造されたわけではありませんが、ある者は永遠の命に、またある者は永遠の破滅に予定されています。したがって、各人はどちらか一方の目的のために創造されたので、その人は生きるか死ぬかが予定されていると言えます。」

- ^ Alexander & Johnson 2016, p. 204: "It should be conceded at the outset, and without any embarrassment, that Calvinism is indeed committed to divine determinism: the view that everything is ultimately determined by God."

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Grudem 1994, p. 692.

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Nicole 1995, p. 400.

- ^ Grudem 1994, p. 970: "The Perseverance of the Saints means that all those who are truly born again will be kept by God's power and will persevere as Christians until the end of their lives, and that only those who persevere until the end have been truly born again."

- ^ Grudem 1994, p. 860: "[T]his doctrine of the perseverance of the saints, if rightly understood, should cause genuine worry, and even fear, in the hearts of any who are 'backsliding' or straying away from Christ. Such persons must clearly be warned that only those who persevere to the end have been truly born again."

- ^ Keathley 2010, p. 171: "John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress has blessed multitudes of Christians, but his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, is disturbing. He recounts how, in his seemingly endless search for assurance of salvation, he was haunted by the question, 'How can I tell if I am elected?'"

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 217: "Calvin, however, has greater confidence than Luther and the Catholic tradition before him that the believer can also have great assurance of his election and final perseverance."

- ^ Sanders 2007, "Summary of Openness of God".

- ^ Picirilli 2002, pp. 40, 59 ff.. Picirilli actually objects so strongly to the link between Arminianism and open theism that he devotes an entire section to his objections.

- ^ Walls & Dongell 2004, p. 45. "[O]pen theism actually moves beyond classical Arminianism towards process theology."

- ^ Olson 2009, p. 199, note 67.

参照資料

[編集]- Abasciano, Brian J. (2005) (英語). Paul's Use of the Old Testament in Romans 9.1–9: An Intertextual and Theological Exegesis. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-03073-3

- AG (2017年). “Assurance-Of-Salvation : Position paper” (英語). 2021年12月15日閲覧。

- Akin, James (1993年). “A Tiptoe Through Tulip” (英語). 2019年6月15日閲覧。

- Alexander, David; Johnson, Daniel (2016) (英語). Calvinism and the Problem of Evil. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publication

- Arminius, Jacobus (1853a) (英語). The Works of James Arminius. 1. Auburn, New York: Derby, Miller & Orton

- Arminius, Jacobus (1853b) (英語). The Works of James Arminius. 2. Auburn, New York: Derby & Miller

- Arminius, Jacobus (1853c) (英語). The Works of James Arminius. 3. Auburn, New York: Derby & Miller

- Bangs, Carl (1960). “Arminius : An Anniversary Report” (英語). Christianity Today 5.

- Bangs, Carl (1985) (英語). Arminius: A Study in the Dutch Reformation. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock

- Barrett, Matthew (2013) (英語). Salvation by Grace: The Case for Effectual Calling and Regeneration. Phillipsburg: P & R Publishing

- Barth, Markus (1974) (英語). Ephesians. Garden City, New Jersey: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-08037-8

- Bender, Harold S. (1953). “Arminianism” (英語). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- Bounds, Christopher. T. (2011). “How are People Saved? The Major Views of Salvation with a Focus on Wesleyan Perspectives and their Implications” (英語). Wesley and Methodist Studies 3: 31–54. doi:10.5325/weslmethstud.3.2011.0031. JSTOR 42909800.

- Calvin, John Henry Beveridge訳 (1845) (英語). Institutes of the Christian Religion; a New Translation by Henry Beveridge. 2. Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society. books 2, 3

- Cameron, Charles M. (1992). “Arminius–Hero or heretic?” (英語). Evangelical Quarterly 64 (3): 213–227. doi:10.1163/27725472-06403003.

- Cross, F. L. (2005) (英語). The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press

- Davis, John Jefferson (1991). “The Perseverance of the Saints: A History of the Doctrine” (英語). Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 34 (2).

- De Jong, Peter (1968). “The Opinions of the Remonstrants (1618)” (英語). Crisis in the Reformed Churches: Essays in Commemoration of the Great Synod of Dordt, 1618–1619. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Reformed Fellowship

- Delumeau, Jean; Wanegffelen, Thierry; Cottret, Bernard (2012). “Chapitre XII: Les conflits internes du protestantisme” (フランス語). Naissance et affirmation de la Réforme. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

- Demarest, Bruce A. (1997) (英語). The Cross and Salvation: The Doctrine of Salvation. Crossway Books. ISBN 978-0-89107-937-8

- Denzinger, Henricus (1954) (英語). Enchiridion Symbolorum et Definitionum (30th ed.). Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder

- Dorner, Isaak A. (2004) (英語). History of Protestant Theology. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock

- Driscoll, Mark (2013) (英語). A Call to Resurgence: Will Christianity Have a Funeral or a Future?. Tyndale House. ISBN 978-1-4143-8907-3

- Elwell, Walter A. (2001) (英語). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Publishing Group. ISBN 9781441200303

- Episcopius, Simon; Ellis, Mark A. (2005). “Introduction” (英語). The Arminian confession of 1621. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications

- Forlines, F. Leroy (2001) (英語). The Quest for Truth: Answering Life's Inescapable Questions. Randall House Publications. ISBN 978-0-89265-962-3

- Forlines, F. Leroy (2011). Pinson, J. Matthew. ed (英語). Classical Arminianism: A Theology of Salvation. Randall House. ISBN 978-0-89265-607-3

- Gann, Gerald (2014). “Arminius on Apostasy” (英語). The Arminian Magazine 32 (2): 5–6.

- Gause, R. Hollis (2007) (英語). Living in the Spirit: The Way of Salvation. Cleveland, Ohio: CPT Press

- Gonzalez, Justo L. (2014) (英語). The Story of Christianity. 2: The Reformation to the Present Day. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-236490-6

- Grider, J. Kenneth (1982). “The Nature of Wesleyan Theology” (英語). Wesleyan Theological Journal 17 (2): 43–57.

- Grider, J. Kenneth (1994) (英語). A Wesleyan Holiness Theology. Kansas City, MO: Beacon Hill Press of Kansas City

- Grudem, Wayne (1994) (英語). Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, Michigan: IVP

- Guggisberg, Hans R.; Gordon, Bruce (2017) (英語). Sebastian Castellio, 1515-1563: Humanist and Defender of Religious Toleration in a Confessional Age. Oxon: Taylor & Francis

- Gunter, William Stephen (2007). “John Wesley, a Faithful Representative of Jacobus Arminius” (英語). Wesleyan Theological Journal 42 (2): 65–82.

- Harmon, Richard W. (1984) (英語). Baptists and Other Denominations. Nashville, Tennessee: Convention Press

- Heron, Alasdair I. C. (1999). “Arminianism”. In Fahlbusch, Erwin (英語). Encyclopedia of Christianity. 1. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 128–129

- James, Frank A. (1998) (英語). Peter Martyr Vermigli and Predestination: The Augustinian Inheritance of an Italian Reformer. Oxford: Clarendon

- Kang, Paul ChulHong (2006) (英語). Justification: The Imputation of Christ's Righteousness from Reformation Theology to the American Great Awakening and the Korean Revivals. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-8605-5

- Keathley, Kenneth D. (2010) (英語). Salvation and Sovereignty: A Molinist Approach. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group

- Keathley, Kenneth D. (2014). “Ch 12. The Work of God: Salvation”. In Akin, Daniel L. (英語). A Theology for the Church. B&H. ISBN 978-1-4336-8214-8

- Keefer, Luke (1987). “Characteristics of Wesley's Arminianism” (英語). Wesleyan Theological Journal 22 (1): 87–99.

- Kirkpatrick, Daniel (2018) (英語). Monergism or Synergism: Is Salvation Cooperative or the Work of God Alone?. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publication

- Knight, Henry H. (2010) (英語). From Aldersgate to Azusa Street: Wesleyan, Holiness, and Pentecostal Visions. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock

- Knight, Henry H. (2018) (英語). John Wesley: Optimist of Grace. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock

- Lange, Lyle W. (2005) (英語). God So Loved the World: A Study of Christian Doctrine. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Northwestern Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-8100-1744-3

- Levering, Matthew (2011) (英語). Predestination: Biblical and Theological Paths. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960452-4

- Loughlin, James Francis (1907). . Catholic Encyclopedia (英語). Vol. 1.

- Luther, Martin (1823) (英語). Martin Luther on the Bondage of the Will: Written in Answer to the Diatribe of Erasmus on Free-will. First Pub. in the Year of Our Lord 1525. London: T. Bensley

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (1990) (英語). The Later Reformation in England 1547–1603. New York: Macmillan International Higher Education

- Magnusson, Magnus, ed (1995). Chambers Biographical Dictionary. Chambers

- Marberry, Thomas (1998). “"Matthew" in the IVP New Testament Commentary Series By Craig S. Keener” (英語). Contact: Official Publication of the National Association of Free Will Baptists. 45. The Association

- Marko, Jonathan S. (2020). “Grace, Early Modern Discussion of”. In Jalobeanu, Dana; Wolfe, Charles T. (英語). Encyclopedia of Early Modern Philosophy and the Sciences. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-20791-9

- McClintock, John; Strong, James (1880). “Arminianism” (英語). The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper and Brothers

- Mcgonigle, Herbert (2001) (英語). Sufficient Saving Grace. Carlisle: Paternoster. ISBN 1-84227-045-1

- More, Ellen (1982). “John Goodwin and the Origins of the New Arminianism” (英語). Journal of British Studies (Cambridge University Press) 22 (1): 50–70. doi:10.1086/385797. JSTOR 175656.

- Muller, Richard A. (2012) (英語). Calvin and the Reformed Tradition: On the Work of Christ and the Order of Salvation. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-4412-4254-9

- Nicole, Roger (1995). “Covenant, Universal Call And Definite Atonement” (英語). Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 38 (3).

- Oakley, Francis (1988) (英語). The Medieval Experience: Foundations of Western Cultural Singularity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Oden, Thomas (2012) (英語). John Wesley's Teachings. 2. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic

- Olson, Roger E. (2008). “The Classical Free Will Theist Model of God”. In Ware, Bruce (英語). Perspectives on the Doctrine of God: Four Views. Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group

- Olson, Roger E. (2009) (英語). Arminian Theology: Myths and Realities. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press

- Olson, Roger E. (2010年). “One more quick sidebar about clarifying Arminianism” (英語). Roger E. Olson: My evangelical, Arminian theological musings. Patheos. 2019年8月27日閲覧。

- Olson, Roger E. (2012年). “My List of "Approved Denominations"” (英語). My evangelical, Arminian theological musings. 2019年9月6日閲覧。

- Olson, Roger E. (2013a). “What's Wrong with Calvinism?” (英語). Roger E. Olson: My evangelical, Arminian theological musings. Patheos. 2018年9月27日閲覧。

- Olson, Roger E. (2013b). “Must One Agree with Arminius to be Arminian?” (英語). Roger E. Olson: My evangelical, Arminian theological musings. Patheos. 2019年12月7日閲覧。

- Olson, Roger E. (2014) (英語). Arminianism FAQ: Everything You Always Wanted to Know. Franklin, Tennessee: Seebed. ISBN 978-1-62824-162-4

- Olson, Roger E. (2018年). “Calvinism and Arminianism Compared” (英語). Roger E. Olson: My evangelical, Arminian theological musings. Patheos. 2019年8月27日閲覧。

- Oropeza, B. J. (2000) (英語). Paul and Apostasy: Eschatology, Perseverance, and Falling Away in the Corinthian Congregation. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Osborne, Grant R.; Trueman, Carl R.; Hammett, John S. (2015) (英語). Perspectives on the Extent of the Atonement: 3 views. Nashville, Tennessee: B & H Academic. ISBN 9781433669712. OCLC 881665298

- Pawson, David (1996) (英語). Once Saved, Always Saved? A Study in Perseverance and Inheritance. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-61066-2

- Peterson, Robert A.; Williams, Michael D. (2004) (英語). Why I am not an Arminian. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press. ISBN 0-8308-3248-3

- Picirilli, Robert (2002) (英語). Grace, Faith, Free Will: Contrasting Views of Salvation. Nashville, Tennessee: Randall House. ISBN 0-89265-648-4

- Pickar, C. H. (1981) (英語). The New Catholic Encyclopedia. 5. Washington, DC: McGraw-Hill

- Pinson, J. Matthew (2002) (英語). Four Views on Eternal Security. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Harper Collins

- Pinson, J. Matthew (2003). “Will the Real Arminius Please Stand Up? A Study of the Theology of Jacobus Arminius in Light of His Interpreters” (英語). Integrity: A Journal of Christian Thought 2: 121–139.

- Pinson, J. Matthew (2011). “Thomas Grantham's Theology Of The Atonement And Justification” (英語). Journal for Baptist Theology & Ministry 8 (1): 7–21.

- Puchniak, Robert (2008). “Pelagius: Kierkegaard's use of Pelagius and Pelagianism” (英語). Kierkegaard and the Patristic and Medieval Traditions. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6391-1

- Reasoner, Vic (2000). “An Arminian Covenant Theology” (英語). Arminian Magazine (Fundamental Wesleyan Publishers) 18 (2).

- Ridderbos, Herman (1997) (英語). Paul: An Outline of His Theology. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4469-9

- Rogers, Katherin (2004). “Augustine's Compatibilism” (英語). Religious Studies 40 (4): 415–435. doi:10.1017/S003441250400722X.

- Rupp, Ernest Gordon; Watson, Philip Saville (1969) (英語). Luther and Erasmus: Free Will and Salvation. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-24158-2

- Sanders, John (30 July 2007). “An introduction to open theism” (英語). Reformed Review 60 (2).

- Sayer, M. James (2006) (英語). The Survivor's Guide to Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- SBC (2000年). “The Baptist Faith and Message” (英語). Southern Baptist Convention. 2019年8月19日閲覧。

- Schaff, Philip (1997) (英語). History of the Christian Church. 3. Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems

- Schaff, Philip (2007). “The Five Arminian Articles, A.D. 1610” (英語). The Creeds of Christendom. 3. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books. pp. 545–549. ISBN 978-0-8010-8232-0

- Schwartz, William Andrew; Bechtold, John M. (2015) (英語). Embracing the Past—Forging the Future: A New Generation of Wesleyan Theology. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock

- Smith, Damian J. (2010) (英語). Crusade, Heresy and Inquisition in the Lands of the Crown of Aragon: (c. 1167 - 1276). Leiden: Brill

- Stanglin, Keith D. (2007) (英語). Arminius on the Assurance of Salvation. Boston, Massachusetts: Brill

- Stanglin, Keith D.; Muller, Richard A. (2009). “Bibliographia Arminiana: A Comprehensive, Annotated Bibliography of the Works of Arminius” (英語). Arminius, Arminianism, and Europe. Boston, Massachusetts: Brill. pp. 263–290

- Stanglin, Keith D.; McCall, Thomas H. (15 November 2012) (英語). Jacob Arminius: Theologian of Grace. New York: Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 978-0-19-975567-7

- Stanglin, Keith D.; McCall, Thomas H. (2021) (英語). After Arminius: A Historical Introduction to Arminian Theology. New York: Oxford University Press

- Stegall, Thomas Lewis (2009) (英語). The Gospel of the Christ: A Biblical Response to the Crossless Gospel Regarding the Contents of Saving Faith. Milwaukee: Grace Gospel Press

- Studebaker, Steven M. (2008) (英語). Defining Issues in Pentecostalism: Classical and Emergent. Euguene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers

- Sutton, Jerry (2012). “Anabaptism and James Arminius: A Study in Soteriological Kinship and Its Implications” (英語). Midwestern Journal of Theology 11 (2): 121–139.

- Teselle, Eugene (2014). “The Background: Augustine and the Pelagian Controversy”. In Hwang, Alexander Y.; Matz, Brian J.; Casiday, Augustine (英語). Grace for Grace: The Debates after Augustine and Pelagius. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9

- Thorsen, Don (2007) (英語). An Exploration of Christian Theology. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books

- Torbet, Robert George (1963) (英語). A History of the Baptists (3rd ed.). Judson Press. ISBN 978-0-8170-0074-5

- Tyacke, Nicholas (1990) (英語). Anti-Calvinists: the rise of English Arminianism, c. 1590–1640. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 978-0-19-820184-7

- Vickers, Jason E. (2009) (英語). Wesley: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: T & T Clark

- Wallace, Dewey D. (2011) (英語). Shapers of English Calvinism, 1660–1714: Variety, Persistence, and Transformation. Oxford University Press

- Walls, Jerry L.; Dongell, Joseph R. (2004) (英語). Why I Am Not a Calvinist. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 0-8308-3249-1

- Wesley, John (1827) (英語). The Works of the Rev. John Wesley. 8. New York: J.& J. Harper

- Wesley, John; Emory, John (1835) (英語). The Works of the Late Reverend John Wesley. 2. New York: B. Waugh and T. Mason

- Wilson, Andrew J. (2017) (英語). The Warning-Assurance Relationship in 1 Corinthians. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck

- Witzki, Steve (2010年). “The Arminian Confession of 1621 and Apostasy” (英語). Society of Evangelical Arminians. 2019年5月25日閲覧。

- Wood, Darren Cushman (2007). “John Wesley's Use of the Atonement” (英語). The Asbury Journal 62 (2): 55–70.

- Wynkoop, Mildred Bangs (1967) (英語). Foundations of Wesleyan-Arminian Theology. Kansas City, Missouri: Beacon Hill Press

関連項目

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]- Remonstrant Church - オランダのレモンストラント教会。

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch