化石燃料淘汰 - 维基百科,自由的百科全书

逐步淘汰化石燃料(英語:Fossil fuel phase-out)指的是依循步驟把化石燃料的使用和生產減少到零的程度,以減少空氣污染導致的人類死亡和疾病、限制氣候變化,並強化各國自身的能源獨立。此為能源轉型行動中的一種,但在實施時卻受到化石燃料補貼的阻礙。

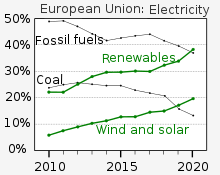

全球許多國家正採取關閉燃煤發電廠的策略,[6][7][8]使用化石燃料發電被認為已經達峰值。[9]但目前的電力生產仍有高比例是依賴燃燒煤炭達成,導致有氣候目標難以實現的風險。[10]許多國家已設定日期以停止銷售依賴汽油和柴油驅動的汽車和卡車,但在停止燃燒天然氣的時間表上則尚未達成協議。[11]

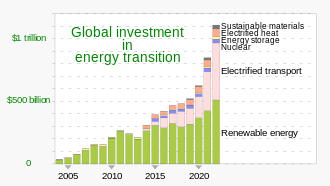

目前逐步淘汰化石燃料的行動中包含有在交通運輸和取暖等領域以永續能源取代化石燃料。取代化石燃料的方法有電氣化、使用綠氫和生物燃料。淘汰的步驟包括在需求方和供給方的措施,[12]前者設法減少化石燃料消耗,而後者則設法限制生產,以加速能源轉型並減少溫室氣體排放。有建議應通過法律,要求化石燃料業者在其排放碳時,也應封存相同數量的碳以作補償。[13]國際能源署估計要在本世紀中葉實現淨零排放,全球到2030年的再生能源投資必須增加兩倍,達到每年4兆(萬億)美元以上。[14][15]

範圍

[编辑]| 系列之一 |

| 氣候變化緩解 |

|---|

雖然有循環經濟和生物經濟(例如生物塑膠)的推動[16]以減少塑膠污染,過程中也發生逐步減少石油和天然氣的使用,但逐步淘汰化石燃料的具體目標是結束使用化石燃料以及由此產生的溫室氣體。因此此種塑膠產業的做法並不能達到預定的目標。

化石燃料種類

[编辑]煤炭

[编辑]為實現《巴黎協定》中將全球升溫控制在遠低於2°C (3.6°F) 的目標(與第一次工業革命前的全球平均氣溫比較),全球在2020年到2030年期間須將煤碳使用量減少一半。[20]然而截至2017年,煤碳仍佔全球一次能源用量的四分之一以上,[21]在化石燃料溫室氣體排放量中的佔比約為40%。[22]逐步淘汰煤碳在短期健康和環境上的效益遠高於花費的成本,[23]如果不如此做,《巴黎協定》設定的控制升溫目標目標就無法實現,[24]但有些國家仍然偏好使用煤碳,[25]且對淘汰的速度有很不同的看法。[26][27]

截至2018年,已有30個國家和許多地方政府和企業[28]成為超越燃煤聯盟的成員,承諾逐步淘汰未附設減排設施的燃煤發電廠("減排"意指實施碳捕集與封存 (CCS) 技術,但由於CCS成本過高,絕大部分發電廠都並未減排)。[29]然而截至2019年,全球使用煤碳數量最大的國家尚未加入聯盟,一些國家仍在繼續建造和資助新的燃煤發電廠。歐洲復興開發銀行支持不再使用煤碳的能源轉型,但過程必須是公正的。[30]

時任聯合國秘書長安東尼歐·古特瑞斯於2019年表示各國應自2020年起停止興建新的燃煤電廠,否則全球將面臨"全面災難"。[31]

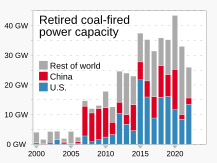

雖然中國於2020年建造一些新的燃煤電廠,但全球除役的數量多於建成的,聯合國秘書長表示經合組織(OECD)國家應在2030年之前停止使用燃煤發電,其他地區應在2040年之前停止。[32]

石油

[编辑]

石油原油經精煉後成為燃料油、柴油和汽油,主要用作傳統汽車、卡車、火車、飛機和船舶運輸的燃料之用。而目前提倡的替代方案是人力運輸、大眾運輸、電動載具和使用生物燃料。[33]

天然氣

[编辑]

天然氣被大量用於發電之用,其排放強度約為500克/度(度=千瓦)。取暖用的能源也是產生二氧化碳的主要來源。開採過程中發生的洩漏也是大氣中甲烷的一個重要來源。

一些國家將天然氣作為替代煤碳的短期性"過渡燃料",之後使用再生能源或氫氣取代。[34]然而這種"過渡燃料"可能會顯著延長化石燃料的使用,例如於2020年代建造的燃氣發電廠,其平均壽命有35年。[35]因此天然氣設施除役的時間可能會晚於石油和煤碳設施,但一些投資者會擔心由此涉及的商譽風險。[36]

世界有些地區的逐步淘汰天然氣行動已取得進展,例如歐洲輸天然氣系統運營商網絡(ENTSOG) [37]正利用既有管線設備,導入氫氣的使用,以及改變建築法規以減少燃少天然氣取暖。[38][39]

原因

[编辑]常見的逐步淘汰化石燃料原因是:

健康

[编辑]因空氣污染已導致全球每年有數百萬人[43]過早死亡,其中大多數是由化石燃料所造成[44](估計這一比例為65%,即350萬人因之死亡[45])。污染可能發生在室內,例如因取暖和烹飪,或戶外汽車產生的廢氣。倫敦衛生與熱帶醫學院教授及流行病學專家安迪·海恩斯爵士表示,以金錢衡量的逐步淘汰化石燃料的健康效益(由經濟學家根據每個國家的生命價值估算)遠高於根據《巴黎協定》實現控制全球升溫在2°C內目標的成本。[46]

氣候變化緩解

[编辑]逐步淘汰化石燃料可限制導致全球暖化的最大因素 - 所排放的溫室氣體數量佔全球總量的70%以上。[47]國際能源署於2020年表示為實現《巴黎協定》的目標,逐步淘汰化石燃料需要比目前"快上四倍的速度"。[48]為實現將全球升溫限制在比前工業化時代水準不超過1.5°C的目標,國家和公司擁有的絕大多數化石燃料儲備(迄2021年)必須讓其留在地下,不得開採。[49][50]

就業

[编辑]往再生能源轉型可經由建造新型發電廠和製造相關設備來創造就業機會,正如德國和風能發電產業所呈的案例。[51]

能源獨立

[编辑]通常缺乏化石燃料儲量(特別是煤碳,還有石油和天然氣)的國家,會把取得能源獨立作為淘汰化石燃料的原因。

瑞士考慮到兩次世界大戰(瑞士均保持中立)期間的煤碳進口變得越來越困難,因此決定將國內鐵路網全面電氣化。瑞士擁有豐富的水力資源,電動火車可使用由此生產的電力,而減少煤碳進口需求。[52][53]

發生於1973年的第一次石油危機也導致許多地方的能源政策轉變,試圖擺脫進口化石燃料的影響。法國政府宣佈一項恢弘的核能發電計劃,到1980年代末,該國電力部門幾乎完全從使用天然氣和石油轉而使用核子動力。[54][55]

荷蘭[56][57]和丹麥[58][59]在第一次石油危機發生時鼓勵國民騎自行車通勤,部分原因是在減少交通運輸部門對石油進口的依赖。

逐步取消化石燃料補貼

[编辑]有許多國家提供大量化石燃料補貼。[60]許多國家[61]於2019年提供的化石燃料消費補貼總額達3,200億美元。[62]截至2019年,各國政府每年補貼化石燃料(包括對於探勘與開採的補貼)約為5,000億美元,然而國際貨幣基金組織(IMF)採用非常規的補貼定義(將未對溫室氣體排放定價也計入),估計全球於2017年的化石燃料補貼為5.2兆(萬億)美元,佔全球國內生產毛額(GDP)的6.4%。[63]一些化石燃料公司透過遊說政府,延緩能源轉型進程(參見化石燃料業者遊說)。[64]

逐步取消化石燃料補貼對於解決氣候危機非常重要,[65]但必須謹慎進行,以避免發生大規模抗議事件[66]並導致窮人變得更窮。[67]然而在大多數情況下,較低的化石燃料價格會讓富裕家庭比貧困家庭受益更多。為幫助貧困和弱勢群體,採用化石燃料補貼以外的措施必須更有針對性的做法。[68]但這又反過來會增加民眾對補貼改革的支持。[69]

全球研究顯示即使不引入稅收,將補貼和在部門層面上消除貿易障礙也可提高效率並減少環境破壞。[70]取消這些補貼將大幅減少溫室氣體排放並創造再生能源部門的就業機會。[71]IMF於2023年預計,取消化石燃料補貼將可把全球升溫限制在巴黎目標所定的2°C以下。[72]

取消化石燃料補貼的實際效果在很大程度上取決於取消的補貼類型以及其他能源的可用程度和經濟性。[70]此外還有碳洩漏的問題,取消對高能源強度產業的補貼可能會導致它們被轉移到監管較少的別國,反而導致全球排放量淨增加。

在已開發國家,能源成本低廉且補貼豐厚,而在開發中國家,窮人卻得為低品質的服務付出高昂的成本。[73]

一篇於2009年發表的研究報告,提出在2030年前將全球電力100%由風能、水力和太陽能提供的計畫。[74][75]報告建議將能源補貼從化石燃料轉向再生能源,並制定將洪水、颶風、颱風、乾旱和相關極端天氣成本包含在內的碳定價。

自2021年起,如果將石化燃料補貼排除在外,印度和中國新建大型太陽能發電的平均化電力成本均低於現有的燃煤發電廠。[76]

位於美國德克薩斯州的萊斯大學能源研究中心發表的一項研究,建議各國採取以下步驟:[41]

- 各國應承諾在具體時限內全面取消隱性和顯性的化石燃料補貼。

- 澄清補貼改革的措辭,消除含糊用語。

- 在受影響國家中正式立法,制定改革路徑並減少退步的機會。

- 公佈透明,與市場掛鉤的定價公式,並遵守定期價格調整時間表。

- 循序漸進推動全面改革。逐步但按規定時間表向消費者表明提高價格的意圖,同時投資於改善能源效率以部分抵銷價格的上漲。

- 透過對化石能源產品和服務徵收費用或稅收,並消除稅法中仍然存在對化石燃料的優惠,逐步將其外部性納入考量。

- 使用直接現金轉移來維持社會貧困階層的福利,而非維持弱勢社會經濟群體的補貼價格。

- 進行全面公共宣導活動。

- 任何剩餘的化石燃料補貼都應按照國際價格明確制定,由國庫支付。

- 根據要求,將價格和排放變化製作記錄及報告。

淘汰的特定流程

[编辑]逐步淘汰化石燃料發電廠

[编辑]

在逐步淘汰化石燃料時,能源效率與使用永續能源兩者有相輔相成的作用。

逐步淘汰化石燃料汽車

[编辑]

許多國家和城市已禁止銷售新造內燃機汽車,並要求所有新車均為電動載具或使用清潔、無排放的能源,[80][81]例如英國要求到2035年達成[82]和挪威要求到2025年達成。許多大眾運輸機構正致力於全面採用電動巴士,同時限制燃油車輛在市中心行駛,以降低空氣污染。美國許多州都制定有零排放載具指令,逐步要求銷售的汽車中有一定比例為電動車。德國用語Verkehrswende("交通轉型"之義),呼籲從內燃機驅動的道路運輸轉向自行車、步行和鐵路運輸,並用電動車取代其餘道路車輛。

從植物提煉的的生物燃料也被引進市場。然而目前市面供應的許多生物燃料因其對自然環境、糧食安全和土地利用會產生不利影響而受到批評。[83][84]

逐步淘汰石油燃料

[编辑]

透過減少石油消耗,可改變哈伯特曲線的形狀,哈伯特曲線是哈伯特峰值理論所預測的石油實際產量隨時間變化的圖形。 曲線的峰值稱為石油峰值,通過改變曲線的形狀,石油產量抵達峰值時間會受到影響。 在赫希報告中,撰寫者的分析顯示雖然石油產量曲線的形狀會受到減緩措施的影響,但減緩措施也會受到哈伯特曲線形狀的影響。.[85]

在大多數情況下,緩解措施涉及節約能源以及使用替代能源和再生能源。非常規石油資源的開發可擴大石油供應,[86]但並不會減少消耗。

根據史上的世界石油消費數據,1973年和1979年石油危機期間的緩解措施可降低石油消費。在美國,石油消費會因為價格高漲下降。[87][88]

採行緩解措施的主要問題是方法的可行性、政府和私營部門的角色以及這些解決方案提前多久實施。[89][90]對這些問題的答案和採取的緩解措施能決定一個社會的生活方式是否能夠維持,並可能影響地球的人口容量。

緩解石油峰值最有效的方法是使用再生或替代能源以取代石油。

由於大多數石油消耗均用於交通運輸,[91]大多數的緩解討論都圍繞著此類問題進行。

移動應用

[编辑]由於石油的能量密度高且易於處理,在運輸上具有獨特的作用。然而目前已有許多可用的替代方案。在生物燃料部分,一些國家已在一定程度上開始使用生物乙醇和生質柴油。

氫燃料是各國開發中的另一種替代方案,同時開發的還有氫能載具,[92]氫實際上是一種儲能介質,而非一次能源,因此需要使用非石油能源製造氫氣。氫氣目前在成本和效率方面優於電池驅動車輛,[93]在某些應用中可派上用場 - 短途渡輪和在非常寒冷的氣候中使用就是其中兩例。氫燃料電池的效率約為電池的三分之一,是汽油車效率的兩倍。

替代航空燃料

[编辑]空中巴士A380於2008年2月1日首次使用替代燃料飛行。[94]波音也計畫讓波音747使用替代燃料。[95]由於乙醇等一些生物燃料所含的能量密度較低,因此此類飛機需要更頻繁加油。

美國空軍目前正在為其整個機隊使用源自費托合成的燃料和JP-8航空煤油各佔一半的混合燃料作認證。[96]

研究工作

[编辑]

綠色和平組織和歐洲氣候行動網絡於2015年發佈一份報告,強調歐洲各地積極逐步淘汰燃煤發電的必要性。他們的分析源自對280家燃煤電廠的資料庫,及來自歐盟官方登記處的排放數據而得結論。[100]

國際石油變革組織(Oil Change International)於2016年發佈的一份報告,結論是假設目前正在作業的礦山和油田的煤碳、石油和天然氣的碳排放量一直持續到其工作壽命結束,將使世界的碳排放量略高於2015年《巴黎協定》中所設定的2°C升溫限制,而大幅超越保守的1.5°C目標。[101][102][103]報告指出,"最強有力的氣候政策槓桿之一,也是最簡單的:停止開採更多化石燃料。"[103]:5

智庫海外發展研究所(ODI)和其他11個非政府組織於2016年發佈一份報告,內容涉及在很大部分人口無電力可用的國家建設新燃煤電廠的影響。報告的結論是總體上,建造燃煤電廠對窮人沒什麼幫助,而且可能會讓他們變得更窮。此外,風能和太陽能發電的建廠成本已開始低於燃煤的。[104][105][106]

一篇於2008年刊載在科學月刊自然能源的研究報告說歐洲10個國家可利用其現有基礎設施完全淘汰燃煤發電,而美國和俄羅斯可逐步淘汰至少其中的30%。[107]

成立於2018年的化石燃料削減資料庫(Fossil Fuel Cuts Database)於2020年提供全球首份關於限制化石燃料生產的供應端倡議的綜合報告。[108]根據最近更新的資料庫,截至2021年10月,全球110個國家已實施1967項始於1988年的供應端倡議,涵蓋七種類型 (撤資,數量 = 1201、封鎖,數量 = 374、訴訟,數量 = 192、暫停令和禁令,數量 = 146、取消生產補貼,數量 = 31、碳排放稅,數量 = 16及排放交易計劃,數量 = 7)

地緣政治利弊指數(GeGaLo index of geopolitical gains and losses)評估,如果世界完全轉而使用再生能源,156個國家的地緣政治地位可能發生變化。前化石燃料出口國預計將失去影響力,而前化石燃料進口國和再生能源資源豐富的國家的地位預計將可加強。[109]

已有多項實現二氧化碳零排放的脫碳計畫被提出。

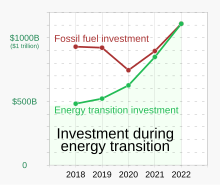

英國《衛報》所做的一項調查顯示到2022年,大型化石燃料公司仍繼續對新的化石燃料生產項目進行巨額投資,而會導致全球升溫程度超過國際共同設定的限制目標。[110]

再生能源潛力

[编辑]雪梨科技大學永續未來研究所(Institute for Sustainable Futures)的Sven Teske博士和Sarah Niklas博士於2021年6月發表報告,提出"現有的煤碳、石油和天然氣生產讓世界溫室氣體排放遠高於《巴黎協定》設定全球升溫的目標。他們與化石燃料不擴散條約倡議組織共同發佈一份題為《化石燃料退出戰略:有序減少煤炭、石油和天然氣以滿足《巴黎協定》目標的報告。報告中分析全球再生能源潛力,發現"地球上每個地區都可使用再生能源取代化石燃料,將升溫控制在1.5°C以下,並為所有人提供可靠的能源。"[111]

開採預防責任評估

[编辑]於2021年9月,有項首次對每個地區以及全球需要開採的化石燃料的最低數量進行科學評估,以便有50%的可能在2050年將全球升溫限制在1.5°C的程度。[112][113]

挑戰

[编辑]

進行逐步淘汰化石燃料會碰到許多挑戰,其中之一是目前世界對化石燃料的依賴。化石燃料於2014年提供世界一次能源消耗的80%以上。[116]根據一份於2023年6月發表的報導,此佔比在2022年仍維持在80%左右。[117]

逐步淘汰化石燃料可能會導致電價上漲,因為需要對新設備進行投資,以配合替代能源使用。[118]

逐步淘汰化石燃料的另一個影響是就業。就化石燃料行業的從業者而言,逐步淘汰並不受到歡迎,他們通常會反對任何變動。[51]兩位研究人員Endre Tvinnerreim和Elisabeth Ivarsflaten研究化石燃料產業就業與對氣候變化政策支持之間的關係。他們提出地熱能發電可能可提供化石燃料產業鑽勘人員轉業的機會。他們的結論:化石燃料產業的個人和公司可能會反對危及其就業的措施,除非有其他更好的替代方案。[119]這可被推論為政治利益,推動反對逐步淘汰化石燃料的倡議。[120]其中一例是美國國會議員的投票傾向與其來自州別化石燃料產業的影響力有關聯。[121]

除前述的挑戰外,其他難題還包括確保可持續回收、採購所需材料、破壞現有電力結構、管理間歇性再生能源、制定最佳的國家能源轉型政策、改造交通基礎設施以及預防化石燃料開採的責任。目前有關這些問題的研究和發展正在積極進行中 [122][123][124]

據參加埃及主辦的2022年聯合國氣候變化大會的人士稱,沙烏地阿拉伯代表極力阻止減少燃燒石油的呼籲。大會的最終聲明經沙烏地阿拉伯和其他一些石油生產國的反對後,未能將逐步淘汰化石燃料的呼籲包含在內。 於2022年3月,在一項聯合國與氣候科學家舉行的會議上,沙烏地阿拉伯與俄羅斯一起推動將"人類引起的氣候變化"文字從官方文件中刪除,擾亂科學確定的事實,即人類燃燒化石燃料是產生氣候危機的主要驅動因素。[125]

主要倡議和立法

[编辑]中國

[编辑]中國已承諾在2060年實現淨零排放,這需要對煤碳開採和電力產業超過300萬從業者進行公正轉型。[126]目前尚不清楚中國是否打算在彼時淘汰所有化石燃料的使用,或者是否仍保留一小部分(配合使用碳捕集和與封存設施)。[126]中國的煤碳開採於2021年奉命滿載運作。[127]

歐盟

[编辑]歐盟於2019年底推出歐洲綠色協議,其中包括:

- 修訂歐盟能源稅收指令,密切關注化石燃料補貼和免稅(航空、航運兩個產業)

- 循環經濟行動計劃,[128]

- 對所有相關氣候相關政策工具(包括歐盟排放交易體系)進行審查和進行修訂(如有需要)

- 可持續的智慧移動策略

- 對那些不以同樣速度減少溫室氣體污染的國家可能會徵收環保關稅。[129]實現此目標的機制稱為歐盟碳邊境調整機制(CBAM)。[130]

歐盟還依靠歐洲地平線(一項為期7年的歐盟科學研究計劃)在利用國家公共和私人投資方面發揮制衡作用。透過與產業和成員國的合作,歐盟將支持交通技術的研究和創新,包括電池、綠氫、低碳鋼鐵製造、循環生物產業和建成環境。[131]

根據歐盟能源政策,歐洲投資銀行在2017年至2022年間已捐贈超過810億歐元來幫助能源產業。其中包括近760億歐元用於歐洲和世界其他地區與輸電網路、能源效率和再生能源相關的措施。[14]

印度

[编辑]印度有信心超越其根據《巴黎協定》提出的自訂承諾[132] - 即到2030年實現非化石燃料發電量佔其總發電量的40%。[133]

日本

[编辑]日本承諾最晚在2050年實現淨零排放。[134]

英國

[编辑]英國承諾到2050年實現淨零排放,停止使用天然氣為家庭供暖可能是該國逐步淘汰化石燃料過程中最困難的部分。[135]該國有多個團體已提出替代性綠色復甦立法計劃,促進在技術允許的情況下盡快逐步淘汰化石燃料。[136]

知名支持者

[编辑]

支持燃煤電廠建設凍結或逐步淘汰煤碳的知名人士有:

如果你是個年輕人,看著這個星球的未來,看著現在正在做的事和沒有做的事,我相信大家已經進入公民抗命的階段,以阻止新建未附設碳捕集與封存設施的燃煤發電廠。

- 時任Google執行長艾立克·施密特呼籲全球在二十年內用再生能源取代所有化石燃料。[138]

- 時任《聯合國氣候變化綱要公約》執行秘書克里斯蒂娜·菲格雷斯說:"那些繼續投資新化石燃料探勘、開發的公司已公然違反其信託義務,因為科學已清楚顯示我們不能再做這種事情。"[139]

參見

[编辑]

參考文獻

[编辑]- ^ Energy Transition Investment Hit $500 Billion in 2020 – For First Time. Bloomberg New Energy Finance. 2021-01-19. (原始内容存档于2021-01-19).

- ^ Catsaros, Oktavia. Global Low-Carbon Energy Technology Investment Surges Past $1 Trillion for the First Time - Figure 1. Bloomberg NEF (New Energy Finance). 2023-01-26. (原始内容存档于2023-05-22).

Defying supply chain disruptions and macroeconomic headwinds, 2022 energy transition investment jumped 31% to draw level with fossil fuels

- ^ Chrobak, Ula; Chodosh, Sara. Solar power got cheap. So why aren't we using it more?. Popular Science. 2021-01-28. (原始内容存档于2021-01-29). ● Chodosh's graphic is derived from data in Lazard's Levelized Cost of Energy Version 14.0 (PDF). Lazard.com. Lazard. 2020-10-19. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-01-28).

- ^ 2023 Levelized Cost Of Energy+. Lazard: 9. 2023-04-12. (原始内容存档于2023-08-27). (Download link labeled "Lazard's LCOE+ (April 2023) (1) PDF—1MB")

- ^ Lazard LCOE Levelized Cost Of Energy+ (PDF). Lazard: 16. June 2024. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于28 August 2024).

- ^ Nearly a quarter of the operating U.S. coal-fired fleet scheduled to retire by 2029. www.eia.gov. [2023-02-21] (英语).

- ^ Australia hastens coal plant closures to catch up on climate. Nikkei Asia. [2023-02-21] (英国英语).

- ^ Our members. PPCA. 2022-08-02 [2023-02-21] (英语).

- ^ Cuff, Madeleine. Renewables supply 30 per cent of global electricity for the first time. New Scientist. [2024-05-26] (美国英语).

- ^ Coal-Fired Electricity – Analysis. IEA. [2023-02-21] (英国英语).

- ^ No EU agreement on fossil phase-out text. Argus Media. 2023-02-20 [2023-02-21]. (原始内容存档于2023 -02-20) (英语).

- ^ Green, F.; Denniss, R. Cutting with both arms of the scissors: the economic and political case for restrictive supply-side climate policies. Climatic Change. 2018, 150 (1): 73–87. Bibcode:2018ClCh..150...73G. S2CID 59374909. doi:10.1007/s10584-018-2162-x

.

. - ^ Fossil fuel producers must be forced to 'take back' carbon, say scientists. The Guardian. 2023-01-12 [2023-01-12] (英语).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Bank, European Investment. Energy Overview 2023 (报告). 2023-02-02 (英语).

- ^ Nations, United. Renewable energy – powering a safer future. United Nations. [2023-03-09] (英语).

- ^ EU's circular economy action plan released in 2020 A.D.. [2020-10-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-29).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Retired Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker. Global Energy Monitor. 2023. (原始内容存档于2023-04-09). — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Shared attribution: Global Energy Monitor, CREA, E3G, Reclaim Finance, Sierra Club, SFOC, Kiko Network, CAN Europe, Bangladesh Groups, ACJCE, Chile Sustentable. Boom and Bust Coal / Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline (PDF). Global Energy Monitor: 3. 2023-04-05. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-04-07).

- ^ New Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker. Global Energy Monitor. 2023. (原始内容存档于2023-03-19). — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Analysis: Why coal use must plummet this decade to keep global warming below 1.5C. Carbon Brief. 2020-02-06 [2020-02-08]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-16).

- ^ Statistics. iea.org. [2019-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-28).

- ^ China's unbridled export of coal power imperils climate goals. [2018-12-07]. (原始内容存档于2018-12-06).

- ^ Coal exit benefits outweigh its costs – PIK Research Portal. pik-potsdam.de. [2020-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2020-03-24).

- ^ The Production Gap Executive Summary (PDF). [2019-11-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-11-21).

- ^ In coal we trust: Australian voters back PM Morrison's faith in fossil fuel. Reuters. 2019-05-19 [2019-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-28).

- ^ Rockström, Johan; et al. A roadmap for rapid decarbonization (PDF). Science. 2017, 355 (6331): 1269–1271 [11 September 2020]. Bibcode:2017Sci...355.1269R. PMID 28336628. S2CID 36453591. doi:10.1126/science.aah3443. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-14).

- ^ Time for China to Stop Bankrolling Coal. The Diplomat. 2019-04-29 [2019-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-06).

- ^ Powering Past Coal Alliance members list. Poweringpastcoal.org. [2018-09-20]. (原始内容存档于2019-03-27).

- ^ Powering Past Coal Alliance declaration. Poweringpastcoal.org. [2018-09-20]. (原始内容存档于2019-02-02).

- ^ The EBRD's just transition initiative. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. [2020-08-04]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-29).

- ^ UN Secretary-General calls for end to new coal plants after 2020. Business Green. 2019-05-10 [2019-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-19) (英语).

- ^ The dirtiest fossil fuel is on the back foot. The Economist. 2020-12-03 [2021-01-01]. ISSN 0013-0613. (原始内容存档于2021-11-19).

- ^ Clean Vehicles. [2018-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2018-12-15).

- ^ COP26 Energy Transition Council launched. GOV.UK. 2020-09-21 [2020-10-25]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-06) (英语).

In the next phase of this partnership, we must focus even more strongly on working with business to accelerate the development of solutions that are critical to achieve net zero, such as energy storage and clean hydrogen production.

- ^ Natural Gas as a Bridge Fuel : Measuring the Bridge (PDF). Energycenter.org. 2016 [2017-06-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-04-24).

- ^ Stranded assets are an increasing risk for investors. Raconteur. 2019-03-21 [2019-05-26]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-10) (英国英语).

- ^ Simon, Frédéric. Gas network chief: 'By 2050, we assume CO2 emissions from energy will be zero'. euractiv.com. 2019-03-27 [2019-05-26]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-26) (英国英语).

- ^ Preparing Dutch homes for a natural gas-free future. European Climate Foundation. [2019-05-26]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-26) (美国英语).

- ^ Seattle Bans Natural Gas in New Buildings. The National Law Review. [2021-03-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-16) (英语).

- ^ End fossil fuel subsidies and reset the economy – IMF head. World Economic Forum. 2020-06-03 [2020-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-28) (英语).

- ^ 41.0 41.1 Krane, Jim; Matar, Walid; Monaldi, Francisco. Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform Since the Pittsburgh G20: A Lost Decade?. Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy. October 2020 [2020-10-27]. doi:10.25613/sk5h-f056. (原始内容存档于2021-11-19).

- ^ A New World The Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation (PDF). IRENA. 2019 [2024-06-30].

- ^ Carrington, Damian. Air pollution deaths are double previous estimates, finds research. The Guardian. 2019-03-12 [2019-03-12]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-04).

- ^ Ramanathan, V.; Haines, A.; Burnett, R. T.; Pozzer, A.; Klingmüller, K.; Lelieveld, J. Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019-04-09, 116 (15): 7192–7197. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.7192L. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6462052

. PMID 30910976. doi:10.1073/pnas.1819989116

. PMID 30910976. doi:10.1073/pnas.1819989116  (英语).

(英语). - ^ Rapid global switch to renewable energy estimated to save millions of lives annually. LSHTM. [2019-06-02]. (原始内容存档于2020-03-02) (英语).

- ^ Letters to the editor. The Economist. 2019-05-09 [2019-06-02]. ISSN 0013-0613. (原始内容存档于2019-06-23).

- ^ Trends in global CO2 and total greenhouse gas emissions: 2019 Report (PDF). [2020-10-25]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于202-10-31).

- ^ COP26 Energy Transition Council launched. GOV.UK. 2020-09-21 [2020-10-25]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-06) (英语).

The International Energy Agency has told us that to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, the global transition to clean power needs to move four times faster than our current pace.

- ^ Welsby, Dan; Price, James; Pye, Steve; Ekins, Paul. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature. 2021-09-08, 597 (7875): 230–234. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..230W. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34497394. S2CID 237455006. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03821-8

(英语).

(英语). - ^ Damian, Carrington. How much of the world's oil needs to stay in the ground?. The Guardian. 2021-09-08 [2021-09-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-19) (英语).

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Heinrichs, Heidi Ursula; Schumann, Diana; Vögele, Stefan; Biß, Klaus Hendrik; Shamon, Hawal; Markewitz, Peter; Többen, Johannes; Gillessen, Bastian; Gotzens, Fabian. Integrated assessment of a phase-out of coal-fired power plants in Germany. Energy. 2017-05-01, 126: 285–305. Bibcode:2017Ene...126..285H. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.03.017.

- ^ Elektrifizierung 2.0. October 2021.

- ^ Boss, Stefan. Unter Strom – wie die Schweiz elektrifiziert wurde. swissinfo.ch. 2018-07-18. 已忽略未知参数

|lang=(建议使用|language=) (帮助) - ^ Why France has a nuclear-powered economy — and America doesn't | AEI.

- ^ France Presses Ahead with Nuclear Power. NPR.org.

- ^ America, the Netherlands, and the Oil Crisis: 50 Years Later. 2019-04-26.

- ^ Why is cycling so popular in the Netherlands?. BBC News. 2013-08-07.

- ^ The Danish Solution to the Oil Crisis. 2014-08-10.

- ^ Danish cycling history.

- ^ Browning, Noah; Kelly, Stephanie. Analysis: Ukraine crisis could boost ballooning fossil fuel subsidies. Reuters. 2022-03-08 [2022-04-02] (英语).

- ^ Data – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. oecd.org. [2020-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-10) (英语).

- ^ Energy subsidies – Topics. IEA. [2020-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-26) (英国英语).

- ^ Irfan, Umair. Fossil fuels are underpriced by a whopping $5.2 trillion. Vox. 2019-05-17 [2019-11-23] (英语).

- ^ Laville, Sandra. Fossil fuel big five 'spent €251m lobbying EU' since 2010. The Guardian. 2019-10-24 [2019-11-23]. ISSN 0261-3077 (英国英语).

- ^ Breaking up with fossil fuels. UNDP. [2022-11-24]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-03) (英语).

- ^ Gencsu, Ipek; Walls, Ginette; Picciariello, Angela; Alasia, Ibifuro Joy. Nigeria's energy transition: reforming fossil fuel subsidies and other financing opportunities. ODI: Think change. 2022-11-02 [2022-11-24] (英国英语).

- ^ How Reforming Fossil Fuel Subsidies Can Go Wrong: A lesson from Ecuador. IISD. [2019-11-11] (英语).

- ^ Carrington, Damian. Fossil fuel industry gets subsidies of $11m a minute, IMF finds. The Guardian. 2021-10-06 [2021-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-06) (英语).

- ^ | Fossil Fuel Subsidies. IMF. [2020-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-31) (英语).

- ^ 70.0 70.1 Barker; et al. 9.2.1.2 Reducing Subsidies in the Energy Sector. Climate Change 2001: IPCC Third Assessment Report Working Group III: Mitigation. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2001: 568 [2010-09-01]. (原始内容存档于2009-08-05).

- ^ Fossil Fuel to Clean Energy Subsidy Swaps: How to pay for an energy revolution. IISD. 2019-06-07 [2019-11-23] (英语).

- ^ Fossil Fuel Subsidies. IMF. [2024-01-02] (英语).

Raising fuel prices to their fully efficient levels reduces projected global fossil fuel CO2 emissions 43 percent below baseline levels in 2030—or 34 percent below 2019 emissions. This reduction is in line with the 25-50 percent reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions below 2019 levels needed by 2030 to be on track with containing global warming to the Paris goal of 1.5-2C.

- ^ Hostettler, Silvia; Gadgil, Ashok; Hazboun, Eileen (编). Sustainable Access to Energy in the Global South: Essential Technologies and Implementation Approaches. Cham: Springer. 2015. ISBN 978-3-319-20209-9. OCLC 913742250.

- ^ Jacobson, M.Z. and Delucchi, M.A. (November 2009) "A Plan to Power 100 Percent of the Planet with Renewables" (originally published as "A Path to Sustainable Energy by 2030") Scientific American 301(5):58–65

- ^ Jacobson, M.Z. (2009) "Review of solutions to global warming, air pollution, and energy security" Energy and Environmental Science 2:148-73 doi:10.1039/b809990c (review)

- ^ Runyon, Jennifer. Report: New solar is cheaper to build than to run existing coal plants in China, India and most of Europe. Renewable Energy World. 2021-06-23 (美国英语).

- ^ Energy Transition Investment Now On Par with Fossil Fuel. Bloomberg NEF (New Energy Finance). 2023-02-10. (原始内容存档于2023-03-27).

- ^ The European Power Sector in 2020 / Up-to-Date Analysis on the Electricity Transition (PDF). ember-climate.org. Ember and Agora Energiewende. 2021-01-25. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-01-25).

- ^ Data from McKerracher, Colin. Electric Vehicles Look Poised for Slower Sales Growth This Year. BloombergNEF. 2023-01-12. (原始内容存档于2023-01-12).

- ^ Burch, Isabella. Survey of Global Activity to Phase Out Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (PDF). Climateprotection.org. September 2018 [2019-01-23]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2019-07-24).

- ^ International Trade Governance and Sustainable Transport: The Expansion of Electric Vehicles (PDF). International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development. December 2017 [2019-01-23]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2020-07-31).

- ^ Asthana, Anushka; Taylor, Matthew. Britain to ban sale of all diesel and petrol cars and vans from 2040. The Guardian. 2017-07-25 [2019-01-27]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-26).

- ^ The Royal Society (January 2008). Sustainable biofuels: prospects and challenges, ISBN 978-0-85403-662-2, p. 61.

- ^ Gordon Quaiattini. Biofuels are part of the solution Canada.com, 2008-04-25. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ Robert L. Hirsch. The Shape of World Oil Peaking: Learning From Experience (PDF). [2007-06-21]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2007-06-21).

- ^ Jim Bartis, RAND Corporation. Unconventional Liquid Fuels Overview. 2006 Boston World Oil Conference (PDF). Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas - USA. 2006 [2007-06-28]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-21).

- ^ Frank Langfitt. Americans Using Less Gasoline. NPR. 2008-03-05 [2018-04-02]. (原始内容存档于2009-08-27).

- ^ Marianne Lavelle. Oil Demand Is Dropping, but Prices Aren't. U.S. News & World Report. 2008-03-04 [2017-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2008-10-12).

- ^ President Discusses Advanced Energy Initiative In Milwaukee. [2017-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-05).

- ^ Proposition 87 (PDF). (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2007-06-14).

- ^ EIA - International Energy Outlook 2007 - Figure 33. [2007-08-24]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-12).

- ^ California Hydrogen Activities. California Hydrogen Highway. California Environmental Protection Agency. November 26, 2012 [9 September 2013]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-23).

- ^ Spiryagin, Maksym; Dixon, Roger; Oldknow, Kevin; Cole, Colin. Preface to special issue on hybrid and hydrogen technologies for railway operations. Railway Engineering Science. 2021-09-01, 29 (3): 211. ISSN 2662-4753. S2CID 240522190. doi:10.1007/s40534-021-00254-x

(英语).

(英语). - ^ Airbus A380 becomes first commercial jet to fly on alternative fuel (PDF). The Economic News. 2008-02-01 [2024-06-30].

- ^ Boeing announce plans to accelerate bio-jet fuel development. 8 October 2007 [2008-07-02]. (原始内容存档于2008-07-06).

- ^ SECAF certifies synthetic fuel blends for B-52H. (原始内容存档于2016-03-03).

- ^ Share of cumulative power capacity by technology, 2010-2027. IEA.org. International Energy Agency (IEA). 2022-12-05. (原始内容存档于2023-02-04). Source states "Fossil fuel capacity from IEA (2022), World Energy Outlook 2022. IEA. Licence: CC BY 4.0."

- ^ Bond, Kingsmill; Butler-Sloss, Sam; Lovins, Amory; Speelman, Laurens; Topping, Nigel. Report / 2023 / X-Change: Electricity / On track for disruption. Rocky Mountain Institute. 2023-06-13. (原始内容存档于2023-07-13).

- ^ Data: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, and Ember Climate. Electricity consumption from fossil fuels, nuclear and renewables, 2020. OurWorldInData.org. Our World in Data consolidated data from BP and Ember. 2021-11-03. (原始内容存档于2021-11-03).

- ^ Jones, Dave; Gutmann, Kathrin. End of an era: why every European country needs a coal phase-out plan (PDF). London, UK and Brussels, Belgium: Greenpeace and Climate Action Network Europe. December 2015 [2016-09-14]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-10-17).

- ^ Mathiesen, Karl. Existing coal, oil and gas fields will blow carbon budget – study. The Guardian (London, UK). 23 September 2016 [2016-09-28]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-23).

- ^ Turnbull, David. Fossil Fuel Expansion Has Reached the Sky's Limit: Report (新闻稿). Washington DC, US: Oil Change International. 2016-09-22 [2016-09-27]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-23).

- ^ 103.0 103.1 Muttitt, Greg. The sky's limit: why the Paris climate goals require a managed decline of fossil fuel production (PDF). Washington DC, US: Oil Change International. September 2016 [2016-09-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-01-20).

- ^ Nuccitelli, Dana. Coal doesn't help the poor; it makes them poorer. The Guardian (London, United Kingdom). 2016-10-31 [2016-10-31]. ISSN 0261-3077. (原始内容存档于2020-01-09).

- ^ Granoff, Ilmi; Hogarth, James Ryan; Wykes, Sarah; Doig, Alison. Beyond coal: scaling up clean energy to fight global poverty. Overseas Development Institute (ODI). London, United Kingdom. October 2016 [2016-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-01).

- ^ Granoff, Ilmi; Hogarth, James Ryan; Wykes, Sarah; Doig, Alison. Beyond coal: Scaling up clean energy to fight global poverty — Position paper (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Overseas Development Institute (ODI). October 2016 [2016-10-31]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-02-02).

- ^ Wilson, IAG; Staffell, I. Rapid fuel switching from coal to natural gas through effective carbon pricing (PDF). Nature Energy. 2018, 3 (5): 365–372 [2019-07-04]. Bibcode:2018NatEn...3..365W. S2CID 169652126. doi:10.1038/s41560-018-0109-0. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-05-01).

- ^ Gaulin, N.; Le Billon, P. Climate change and fossil fuel production cuts: Assessing global supply-side constraints and policy implications. Climate Policy. 2020, 20 (8): 888–901 [2021-11-03]. Bibcode:2020CliPo..20..888G. S2CID 214511488. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1725409. (原始内容存档于2021-11-03).

- ^ Overland, Indra; Bazilian, Morgan; Ilimbek Uulu, Talgat; Vakulchuk, Roman; Westphal, Kirsten. The GeGaLo index: Geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition. Energy Strategy Reviews. 2019, 26: 100406. Bibcode:2019EneSR..2600406O. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2019.100406

. hdl:11250/2634876

. hdl:11250/2634876  (英语).

(英语). - ^ Taylor, Damian Carrington Matthew. Revealed: the 'carbon bombs' set to trigger catastrophic climate breakdown. The Guardian. 2022-05-11 [2022-07-05] (英语).

- ^ Niklas, Sarah; Teske, Sven. Fossil Fuel Exit Strategy: An orderly wind down of coal, oil, and gas to meet the Paris Agreement. Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney: 6. June 2021 [2021-07-28]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-11). 已忽略未知参数

|quote-page=(帮助) - ^ Ramirez, Rachel. Majority of remaining fossil fuels must stay in the ground to limit climate crisis below critical threshold, study shows. CNN. [2021-10-18]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-18).

- ^ Welsby, Dan; Price, James; Pye, Steve; Ekins, Paul. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature. September 2021, 597 (7875): 230–234. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..230W. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34497394. S2CID 237455006. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03821-8

(英语).

(英语). - ^ World Energy Investment 2023 (PDF). IEA.org. International Energy Agency: 61. May 2023. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-08-07).

- ^ 115.0 115.1 Bousso, Ron. Big Oil doubles profits in blockbuster 2022. Reuters. 2023-02-08. (原始内容存档于2023-03-31). ● Details for 2020 from the more detailed diagram in King, Ben. Why are BP, Shell, and other oil giants making so much money right now?. BBC. 2023-02-12. (原始内容存档于2023-04-22).

- ^ Key World Energy Statistics (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2016 [2017-05-06]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-10-26).

- ^ Robert Perkins,Henry Edwardes-Evans. Fossil fuels 'stubbornly' dominating global energy despite surge in renewables: Energy Institute. S&P global. 2023-06-26 [2024-06-30].

- ^ Green, R; Staffell, I. Electricity in Europe: exiting fossil fuels?. Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 2016, 32 (2): 282–303. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grw003

. hdl:10044/1/29487

. hdl:10044/1/29487  .

. - ^ Tvinnereim, Endre; Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth. Fossil fuels, employment, and support for climate policies. Energy Policy. 1 September 2016, 96: 364–371. Bibcode:2016EnPol..96..364T. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.05.052

.

. - ^ The West's Nuclear Mistake. MSN. [2021-12-08].

- ^ Cragg, Michael I.; Zhou, Yuyu; Gurney, Kevin; Kahn, Matthew E. Carbon Geography: The Political Economy of Congressional Support for Legislation Intended to Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Production (PDF). Economic Inquiry. 2013-04-01, 51 (2): 1640–1650 [2019-08-29]. S2CID 8804524. SSRN 2225690

. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00462.x. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-06-02).

. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00462.x. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-06-02). - ^ Integrating Variable Renewable Energy: Challenges and Solutions (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. [2021-11-08]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-05-21).

- ^ Rempel, Arthur; Gupta, Joyeeta. Fossil fuels, stranded assets and COVID-19: Imagining an inclusive & transformative recovery. World Development. 2021-10-01, 146: 105608. ISSN 0305-750X. PMC 9758387

. PMID 36569408. S2CID 237663504. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105608 (英语).

. PMID 36569408. S2CID 237663504. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105608 (英语). - ^ Heath, Garvin A.; Silverman, Timothy J.; Kempe, Michael; Deceglie, Michael; Ravikumar, Dwarakanath; Remo, Timothy; Cui, Hao; Sinha, Parikhit; Libby, Cara; Shaw, Stephanie; Komoto, Keiichi; Wambach, Karsten; Butler, Evelyn; Barnes, Teresa; Wade, Andreas. Research and development priorities for silicon photovoltaic module recycling to support a circular economy. Nature Energy. July 2020, 5 (7): 502–510 [2021-06-26]. Bibcode:2020NatEn...5..502H. ISSN 2058-7546. S2CID 220505135. doi:10.1038/s41560-020-0645-2. (原始内容存档于2021-08-21) (英语).

- ^ Tabuchi, Hiroko. Inside the Saudi Strategy to Keep the World Hooked on Oil. The New York Times. 2022-11-21 [2022-11-21].

- ^ 126.0 126.1 Mallapaty, Smriti. How China could be carbon neutral by mid-century. Nature. 2020-10-19, 586 (7830): 482–483. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..482M. PMID 33077972. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02927-9

(英语).

(英语). - ^ China coal output hits record in Nov to ensure winter supply. Reuters. 2021-12-15.

- ^ A new circular economy action plan. [2020-10-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-29).

- ^ Coal Information Overview 2019 (PDF). International Energy Agency. [2020-03-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-05-16).

peak production in 2013

- ^ Initiative. [2020-10-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-21).

- ^ COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS (PDF). [2020-10-23]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-10-24).

- ^ India will exceed its climate commitments: PM Narendra Modi. [2020-12-13]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-13).

- ^ INDC submission. (PDF). [2020-12-12]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-09-28).

- ^ McCurry, Justin. Japan will become carbon neutral by 2050, PM pledges. The Guardian. 2020-10-26 [2020-10-26]. ISSN 0261-3077. (原始内容存档于2021-04-06) (英国英语).

- ^ Hanna Ziady. All 30 million British homes could be powered by offshore wind in 2030. CNN. 2020-10-06 [2020-10-25].

- ^ See McGaughey, E.; Lawrence, M. The Green Recovery Act 2020. Common Wealth. [8 September 2023]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-15). and Green New Deal for Europe (报告) II. 2019.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle. Gore urges civil disobedience to stop coal plants. Reuters. 2008-09-24 [2016-09-22]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-23).

- ^ "Google CEO ERic Schmidt offers energy plan," 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2012-09-20. San Jose Mercury News, 2008-09-09

- ^ Flannery, Tim. Atmosphere of Hope. Solutions to the Climate Crisis. Penguin Books. 2015: 123–124.

資料來源

[编辑]- Renewables 2021 Global Status Report (PDF). Paris: REN21 Secretariat. 2021 [2021-07-25]. ISBN 978-3-948393-03-8. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-06-15).

- Renewables Global Futures Report: Great debates towards 100% renewable energy (PDF). Paris: REN21 Secretariat. 2017 [2021-07-25]. ISBN 978-3-9818107-4-5. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-06-12).

- Kutscher, C.F.; Milford, J.B.; Kreith, F. Principles of Sustainable Energy Systems. Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Series Third. CRC Press. 2019. ISBN 978-0-429-93916-7. (原始内容存档于2020-06-06).

- McGaughey, E.; Lawrence, M. The Green Recovery Act 2020. Common Wealth. [2023-09-08]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-15).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch