ISO/IEC 8859-1

ISO/IEC 8859-1 code page layout | |

| MIME / IANA | ISO-8859-1 |

|---|---|

| Alias(es) | iso-ir-100, csISOLatin1, latin1, l1, IBM819, CP819 |

| Language(s) | English, various others |

| Standard | ISO/IEC 8859 |

| Classification | Extended ASCII, ISO/IEC 8859 |

| Extends | US-ASCII |

| Based on | DEC MCS |

| Succeeded by | |

| Other related encoding(s) | |

ISO/IEC 8859-1:1998, Information technology—8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets—Part 1: Latin alphabet No. 1, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1987. ISO/IEC 8859-1 encodes what it refers to as "Latin alphabet no. 1", consisting of 191 characters from the Latin script. This character-encoding scheme is used throughout the Americas, Western Europe, Oceania, and much of Africa. It is the basis for some popular 8-bit character sets and the first two blocks of characters in Unicode.

As of April 2025[update], 1.1% of all web sites use ISO/IEC 8859-1.[1][2] It is the most declared single-byte character encoding, but as Web browsers and the HTML5 standard[3] interpret them as the superset Windows-1252, these documents may include characters from that set. Some countries or languages show a higher usage than the global average, in 2025 Brazil according to website use, use is at 2.9%,[4] and in Germany at 2.3%.[5][6]

ISO-8859-1 was (according to the standard, at least) the default encoding of documents delivered via HTTP with a MIME type beginning with text/, the default encoding of the values of certain descriptive HTTP headers, and defined the repertoire of characters allowed in HTML 3.2 documents. It is specified by many other standards.[example needed] In practice, the superset encoding Windows-1252 is the more likely effective default[citation needed] and it is increasingly common for UTF-8 to work[clarification needed] whether or not a standard specifies it.[citation needed]

ISO-8859-1 is the IANA preferred name for this standard when supplemented with the C0 and C1 control codes from ISO/IEC 6429. The following other aliases are registered: iso-ir-100, csISOLatin1, latin1, l1, IBM819, Code page 28591 a.k.a. Windows-28591 is used for it in Windows.[7] IBM calls it code page 819 or CP819 (CCSID 819).[8][9][10][11] Oracle calls it WE8ISO8859P1.[12]

Coverage

[edit]Each character is encoded as a single eight-bit code value. These code values can be used in almost any data interchange system to communicate in the following languages (while it may exclude correct quotation marks such as for many languages including German and Icelandic):

Modern languages with complete coverage

[edit]- Afrikaans

- Albanian

- Basque

- Breton

- Corsican

- English

- Faroese

- Galician

- Icelandic

- Ido

- Irish

- Indonesian

- Italian

- Leonese

- Lojban

- Luxembourgish[a]

- Malay[b]

- Manx

- Norwegian[c]

- Occitan

- Portuguese[d]

- Rhaeto-Romanic

- Rotokas

- Scottish Gaelic

- Scots

- Southern Sami

- Spanish

- Swahili

- Swedish

- Tagalog (Latin script)

- Toki Pona

- Walloon

Notes

[edit]- ^ Basic classical orthography

- ^ Rumi script

- ^ Bokmål and Nynorsk

- ^ European and Brazilian

Languages with incomplete coverage

[edit]ISO-8859-1 was commonly used[citation needed] for certain languages, even though it lacks characters used by these languages. In most cases, only a few letters are missing or they are rarely used, and they can be replaced with characters that are in ISO-8859-1 using some form of typographic approximation. The following table lists such languages.

| Language | Missing characters | Typical workaround | Supported by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalan | Ŀ, ŀ (deprecated) | L·, l· | |

| Danish | Ǿ, ǿ (the accent is optional and ǿ is very rare) | Ø, ø or øe | |

| Dutch | IJ, ij (debatable), j́ (in emphasized words like "blíj́f") | digraphs IJ, ij or ÿ; blíjf | |

| Estonian, Finnish | Š, š, Ž, ž (only present in loanwords) | Sh, sh, Zh, zh | ISO-8859-15, Windows-1252 |

| French | Œ, œ, and the very rare Ÿ | digraphs OE, oe; Y or Ý | ISO-8859-15, Windows-1252 |

| German | ẞ (capital ß, used only in all capitals) | digraph SS or SZ | |

| Hungarian | Ő, ő, Ű, ű | Ö, ö, Ü, ü Õ, õ, Û, û (the characters replaced in 8859-2) | ISO-8859-2, Windows-1250 |

| Irish (traditional orthography) | Ḃ, ḃ, Ċ, ċ, Ḋ, ḋ, Ḟ, ḟ, Ġ, ġ, Ṁ, ṁ, Ṗ, ṗ, Ṡ, ṡ, Ṫ, ṫ | Bh, bh, Ch, ch, Dh, dh, Fh, fh, Gh, gh, Mh, mh, Ph, ph, Sh, sh, Th, th | ISO-8859-14 |

| Maltese | Ċ, ċ, Ġ, ġ, Ħ, ħ, Ż, ż | C, c, G, g, H, h, Z, z | ISO-8859-3 |

| Welsh | Ẁ, ẁ, Ẃ, ẃ, Ŵ, ŵ, Ẅ, ẅ, Ỳ, ỳ, Ŷ, ŷ, Ÿ | W, w, Y, y, Ý, ý | ISO-8859-14 |

The letter ÿ, which appears in French only very rarely, mainly in city names such as L'Haÿ-les-Roses and never at the beginning of words, is included only in lowercase form. The slot corresponding to its uppercase form is occupied by the lowercase letter ß from the German language, which did not have an uppercase form at the time when the standard was created.

Quotation marks

[edit]Typographical (6- or 9-shaped) quotation marks are missing, as are any baseline quotation marks used by some of the supported languages. Only « », " ", and ' ' are included. Some fonts will display the spacing grave accent (0x60) and the apostrophe (0x27) as a matching pair of oriented single quotation marks (see Quotation mark § Typewriters and early computers), but this is not considered part of the modern standard.

Superscript digits

[edit]Only 3 superscript digits have been encoded: ² at 0xB2, ³ at 0xB3, and ¹ at 0xB9, lacking the superscript digit 0 and digits 4–9. Additionally, none of the subscript digits have been encoded. A workaround would be to use rich text formatting for the digits not covered by this standard.

Euro sign

[edit]The euro sign was first presented to the public on 12 December 1996.[13] Due to this character set being introduced in 1987, it does not include the euro sign. Later character sets similar to ISO/IEC 8859-1 include a euro sign, such as Windows-1252 and ISO/IEC 8859-15.

History

[edit]ISO 8859-1 was based on the Multinational Character Set (MCS) used by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in the popular VT220 terminal in 1983. It was developed within the European Computer Manufacturers Association (ECMA), and published in March 1985 as ECMA-94,[14] by which name it is still sometimes known. The second edition of ECMA-94 (June 1986)[15] also included ISO 8859-2, ISO 8859-3, and ISO 8859-4 as part of the specification.

The original draft of ISO 8859-1 placed French Œ and œ at code points 215 (0xD7) and 247 (0xF7), as in the MCS. However, the delegate from France, being neither a linguist nor a typographer, falsely stated that these are not independent French letters on their own, but mere ligatures (like fi or fl), supported by the delegate team from Bull Publishing Company, who regularly did not print French with Œ/œ in their house style at the time. An anglophone delegate from Canada insisted on retaining Œ/œ but was rebuffed by the French delegate and the team from Bull. These code points were soon filled with × and ÷ under the suggestion of the German delegation. Support for French was further reduced when it was again falsely stated that the letter ÿ is "not French", resulting in the absence of the capital Ÿ. In fact, the letter ÿ is found in a number of French proper names, and the capital letter has been used in dictionaries and encyclopedias.[16] These characters were added to ISO/IEC 8859-15:1999. BraSCII matches the original draft.

In 1985, Commodore adopted ECMA-94 for its new AmigaOS operating system.[17] The Seikosha MP-1300AI impact dot-matrix printer, used with the Amiga 1000, included this encoding.[citation needed]

In 1990, the first version of Unicode used the code points of ISO-8859-1 as the first 256 Unicode code points.

In 1992, the IANA registered the character map ISO_8859-1:1987, more commonly known by its preferred MIME name of ISO-8859-1 (note the extra hyphen over ISO 8859-1), a superset of ISO 8859-1, for use on the Internet. This map assigns the C0 and C1 control codes to the unassigned code values thus provides for 256 characters via every possible 8-bit value.

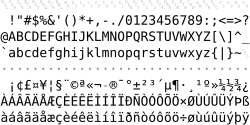

Code page layout

[edit]| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| 0x | ||||||||||||||||

| 1x | ||||||||||||||||

| 2x | SP | ! | " | # | $ | % | & | ' | ( | ) | * | + | , | - | . | / |

| 3x | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | : | ; | < | = | > | ? |

| 4x | @ | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O |

| 5x | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | [ | \ | ] | ^ | _ |

| 6x | ` | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o |

| 7x | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | { | | | } | ~ | |

| 8x | ||||||||||||||||

| 9x | ||||||||||||||||

| Ax | NBSP | ¡ | ¢ | £ | ¤ | ¥ | ¦ | § | ¨ | © | ª | « | ¬ | SHY | ® | ¯ |

| Bx | ° | ± | ² | ³ | ´ | µ | ¶ | · | ¸ | ¹ | º | » | ¼ | ½ | ¾ | ¿ |

| Cx | À | Á | Â | Ã | Ä | Å | Æ | Ç | È | É | Ê | Ë | Ì | Í | Î | Ï |

| Dx | Ð | Ñ | Ò | Ó | Ô | Õ | Ö | × | Ø | Ù | Ú | Û | Ü | Ý | Þ | ß |

| Ex | à | á | â | ã | ä | å | æ | ç | è | é | ê | ë | ì | í | î | ï |

| Fx | ð | ñ | ò | ó | ô | õ | ö | ÷ | ø | ù | ú | û | ü | ý | þ | ÿ |

Undefined Symbols and punctuation Undefined in the first release of ECMA-94 (1985).[14] In the original draft Œ was at 0xD7 and œ was at 0xF7. | ||||||||||||||||

Similar character sets

[edit]ISO/IEC 8859-15

[edit]ISO/IEC 8859-15 was developed in 1999, as an update of ISO/IEC 8859-1. It provides some characters for French and Finnish text and the euro sign, which are missing from ISO/IEC 8859-1. This required the removal of some infrequently used characters from ISO/IEC 8859-1, including fraction symbols and letter-free diacritics: ¤, ¦, ¨, ´, ¸, ¼, ½, and ¾. Ironically, three of the newly added characters (Œ, œ, and Ÿ) had already been present in DEC's 1983 Multinational Character Set (MCS), the predecessor to ISO/IEC 8859-1 (1987). Since their original code points were now reused for other purposes, the characters had to be reintroduced under different, less logical code points.

ISO-IR-204, a more minor modification (called code page 61235 by FreeDOS),[18] had been registered in 1998, altering ISO-8859-1 by replacing the universal currency sign (¤) with the euro sign[19] (the same substitution made by ISO-8859-15).

Windows-1252

[edit]The popular Windows-1252 character set adds all the missing characters provided by ISO/IEC 8859-15, plus a number of typographic symbols, by replacing the rarely used C1 controls in the range 128 to 159 (hex 80 to 9F). It is very common for Windows-1252 text to be mislabelled as ISO-8859-1. A common result was that all the quotes and apostrophes (produced by "smart quotes" in word-processing software) were replaced with question marks or boxes on non-Windows operating systems, making text difficult to read. Many Web browsers and e-mail clients will interpret ISO-8859-1 control codes as Windows-1252 characters, and that behavior was later standardized in HTML5.[20]

Mac Roman

[edit]The Apple Macintosh computer introduced a character encoding called Mac Roman in 1984. It was meant to be suitable for Western European desktop publishing. It is a superset of ASCII, and has most of the characters that are in ISO-8859-1 and all the extra characters from Windows-1252, but in a totally different arrangement. The few printable characters that are in ISO/IEC 8859-1, but not in this set, are often a source of trouble when editing text on Web sites using older Macintosh browsers, including the last version of Internet Explorer for Mac.

Other

[edit]DOS has code page 850, which has all printable characters that ISO-8859-1 has, albeit in a totally different arrangement, plus the most widely used graphic characters from code page 437.

Between 1989[21] and 2015, Hewlett-Packard used another superset of ISO-8859-1 on many of their calculators. This proprietary character set was sometimes referred to simply as "ECMA-94" as well.[21] HP also has code page 1053, which adds the medium shade (▒, U+2592) at 0x7F.[22]

Several EBCDIC code pages were purposely designed to have the same set of characters as ISO-8859-1, to allow easy conversion between them.

See also

[edit]- Latin script in Unicode

- Unicode

- Universal Coded Character Set

- UTF-8

- Windows code pages

- ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2

References

[edit]- ^ "Historical trends in the usage statistics of character encodings for Web sites, December 2024". W3Techs. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- ^ Cowan, John; Soltano, Sam (August 2014). "Source of character encoding statistics?". W3Techs. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Encoding". WHATWG. 27 January 2015. sec. 5.2 Names and labels. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Distribution of Character Encodings among websites that use Brazil". W3Techs. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- ^ "Distribution of Character Encodings among websites that use .de". W3Techs. Retrieved 2025-04-16.

- ^ "Distribution of Character Encodings among websites that use German". W3Techs. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024. Retrieved 2025-04-16.

- ^ "Code Page Identifiers". Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ "Code page 819 information document". Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- ^ "CCSID 819 information document". Archived from the original on 2016-03-27.

- ^ Code Page CPGID 00819 (pdf) (PDF), IBM

- ^ Code Page CPGID 00819 (txt), IBM

- ^ Baird, Cathy; Chiba, Dan; Chu, Winson; Fan, Jessica; Ho, Claire; Law, Simon; Lee, Geoff; Linsley, Peter; Matsuda, Keni; Oscroft, Tamzin; Takeda, Shige; Tanaka, Linus; Tozawa, Makoto; Trute, Barry; Tsujimoto, Mayumi; Wu, Ying; Yau, Michael; Yu, Tim; Wang, Chao; Wong, Simon; Zhang, Weiran; Zheng, Lei; Zhu, Yan; Moore, Valarie (2002) [1996]. "Appendix A: Locale Data". Oracle9i Database Globalization Support Guide (PDF) (Release 2 (9.2) ed.). Oracle Corporation. Oracle A96529-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ^ "Typographers discuss the euro". Evertype. December 1996. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ a b Standard ECMA-94: 8-bit Single-Byte Coded Graphic Character Set (PDF) (1 ed.). European Computer Manufacturers Association (ECMA). March 1985 [1984-12-14]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

[…] Since 1982 the urgency of the need for an 8-bit single-byte coded character set was recognized in ECMA as well as in ANSI/X3L2 and numerous working papers were exchanged between the two groups. In February 1984 ECMA TC1 submitted to ISO/TC97/SC2 a proposal for such a coded character set. At its meeting of April 1984 SC decided to submit to TC97 a proposal for a new item of work for this topic. Technical discussions during and after this meeting led TC1 to adopt the coding scheme proposed by X3L2. Part 1 of Draft International Standard DTS 8859 is based on this joint ANSI/ECMA proposal. […] Adopted as an ECMA Standard by the General Assembly of Dec. 13–14, 1984. […]

- ^ "Second edition of ECMA-94 (June 1986)" (PDF).

- ^ André, Jacques (1996). "ISO Latin-1, norme de codage des caractères européens? Trois caractères français en sont absents!" (PDF). Cahiers GUTenberg (in French) (25): 65–77. doi:10.5802/cg.205.

- ^ Malyshev, Michael (2003-01-10). "Registration of new charset [Amiga-1251]". ATO-RU (Amiga Translation Organization - Russian Department). Archived from the original on 2016-12-05. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ "Cpi/CPIISO/Codepage.TXT at master · FDOS/Cpi". GitHub.

- ^ ITS Information Technology Standardization (1998-09-16). Supplementary set for Latin-1 alternative with EURO SIGN (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-204.

- ^ van Kesteren, Anne (27 January 2015). "5.2 Names and labels". Encoding Standard. WHATWG. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b HP 82240B Infrared Printer (1 ed.). Corvallis, OR, USA: Hewlett-Packard. August 1989. HP reorder number 82240-90014.

- ^ "Code Page 1053" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-21.

External links

[edit]- ISO/IEC 8859-1:1998

- ISO/IEC FDIS 8859-1:1998 Archived 2020-09-30 at the Wayback Machine — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets, Part 1: Latin alphabet No. 1 (draft dated February 12, 1998, published April 15, 1998)

- Standard ECMA-94: 8-Bit Single Byte Coded Graphic Character Sets — Latin Alphabets No. 1 to No. 4 2nd edition (June 1986)

- ISO-IR 100 Right-Hand Part of Latin Alphabet No.1 (February 1, 1986)

- The Letter Database

- Czyborra, Roman (1998-12-01). "The ISO 8859 Alphabet Soup". Archived from the original on 2016-12-01. Retrieved 2016-12-01. [1] [2]

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch