Aq Qoyunlu

Aq Qoyunlu آق قویونلو | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1378–1503[a] | |||||||||||

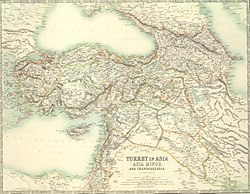

The Aq Qoyunlu confederation at its greatest extent under Uzun Hasan in 1478 | |||||||||||

| Status | Confederate Sultanate | ||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam[8] | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Ruler | |||||||||||

• 1378–1435 | Qara Yuluk Uthman Beg | ||||||||||

• 1497–1503 | Sultan Murad | ||||||||||

| Legislature | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||||

• First raid on the Trapezuntine Empire by Tur Ali Beg[9] | 1340 | ||||||||||

| 1348 | |||||||||||

• Established | 1378 | ||||||||||

• Coup by Uzun Hasan[3] | Autumn 1452 | ||||||||||

• Reunification[3] | 1457 | ||||||||||

| December, 1497 | |||||||||||

• Collapse of the Aq Qoyunlu rule in Iran[3] | Summer 1503 | ||||||||||

• End of the Aq Qoyunlu rule in Mesopotamia[3] | 1508 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Akçe[10] Ashrafi[10] Dinar[10] Tanka[10] Hasanbegî[11] (equal to 2 akçe) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Aq Qoyunlu or the White Sheep Turkomans[c] (Azerbaijani: Ağqoyunlular, آغقویونلولار; Persian: آق قویونلو) was a culturally Persianate,[15][16] Sunni[8] Turkoman[17][18] tribal confederation. Founded in the Diyarbakir region by Qara Yuluk Uthman Beg,[19][20] they ruled parts of present-day eastern Turkey from 1378 to 1503, and in their last decades also ruled Armenia, Azerbaijan, much of Iran, Iraq, and Oman where the ruler of Hormuz recognised Aq Qoyunlu suzerainty.[21][22] The Aq Qoyunlu empire reached its zenith under Uzun Hasan.[3]

History

Etymology

The name Aq Qoyunlu, literally meaning "those with white sheep",[23] is first mentioned in late 14th century sources. It has been suggested that this name refers to old totemic symbols, but according to Rashid al-Din Hamadani, the Turks were forbidden to eat the flesh of their totem-animals, and so this is unlikely given the importance of mutton in the diet of pastoral nomads. Another hypothesis is that the name refers to the predominant color of their flocks.[3]

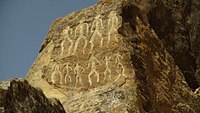

Origins

According to chronicles from the Byzantine Empire, the Aq Qoyunlu are first attested in the district of Bayburt south of the Pontic Mountains from at least the 1340s.[24] In these chronicles, Tur Ali Beg was mentioned as lord of the "Turks of Amid [Diyarbakir]", who had already attained the rank of amir under the Ilkhan Ghazan. Under his leadership, they besieged Trebizond, but failed to take the town.[25] A number of their leaders, including the dynasty's founder, Qara Yuluk Uthman Beg,[26] married Byzantine princesses.[27]

By the end of the Ilkhanid period in the mid-14th century, the Oghuz tribes that comprised the Aq Qoyunlu confederation roamed the summer pastures in Armenia, in particular, the upper reaches of the Tigris river and winter pastures between the towns of Diyarbakır and Sivas. Since the end of the 14th century, Aq Qoyunlu waged constant wars with another tribal confederation of the Oghuz tribes, the Qara Qoyunlu. The leading Aq Qoyunlu tribe was the Bayandur tribe.[23]

Uzun Hasan used to assert the claim that he was an "honorable descendant of Oghuz Khan and his grandson, Bayandur Khan". In a letter dating to the year 1470, which was sent to Şehzade Bayezid, the then-governor of Amasya, Uzun Hasan wrote that those from the Bayandur and Bayat tribes, as well as other tribes that belonged to the "Oghuz il", and formerly inhabited Mangyshlak, Khwarazm and Turkestan, came and served in his court. He also made the tamga (seal) of the Bayandur tribe the symbol of his state. For this reason, the Bayandur tamga is found in Aq Qoyunlu coins, their official documents, inscriptions and flags.[11]

- Myth

The Aq Qoyunlu Sultans claimed descent from Bayindir Khan, who was a grandson of Oghuz Khan, the legendary ancestor of Oghuz Turks.[28]

According to Professor G. L. Lewis:[29]

The Ak-koyunlu Sultans claimed descent from Bayindir Khan and it is likely, on the face of it, that the Book of Dede Korkut was composed under their patronage. The snag about this is that in the Ak-koyunlu genealogy Bayindir's father is named as Gok ('Sky') Khan, son of the eponymous Oghuz Khan, whereas in our book he is named as Kam Ghan, a name otherwise unknown. In default of any better explanation, I therefore incline to the belief that the book was composed before Ak-koyunlu rulers had decided who their ancestors were. It was in 1403 that they ceased to be tribal chiefs and became Sultans, so we may assume that their official genealogy was formulated round about that date.

According to the Kitab-i Diyarbakriyya, the ancestors of Uzun Hasan back to the prophet Adam in the 68th generation are listed by name and information is given about them. Among them is Tur Ali Bey, the grandfather of Uzun Hasan's grandfather, who is also mentioned in other sources. But it is difficult to say whether Pehlivan Bey, Ezdi Bey and Idris Bey, who are listed in earlier periods, really existed. Most of the people who are listed as the ancestors of Uzun Hasan are names related to the Oghuz legend and to Oghuz rulers.[30]

Uzun Hasan

The Aq Qoyunlu Turkomans first acquired land in 1402, when Timur granted them all of Diyar Bakr in present-day Turkey. For a long time, the Aq Qoyunlu were unable to expand their territory, as the rival Qara Qoyunlu or "Black Sheep Turkomans" kept them at bay. However, this changed with the rule of Uzun Hasan, who defeated the Black Sheep Turkoman leader Jahān Shāh in 1467. After the death of Jahan Shah, his son Hasan Ali, with the help of Timurid Abu Sa'id Mirza, marched on Azerbaijan to meet Uzun Hasan. Deciding to spend the winter in Karabakh, Abu Sa'id was captured and repulsed by Uzun Hasan as the former advanced towards the Aras River.[31][page needed][32]

After the defeat of the Timurid leader, Abu Sa'id Mirza, Uzun Hasan was able to take Baghdad along with territories around the Persian Gulf. He expanded into Iran as far east as Khorasan. However, around this time, the Ottoman Empire sought to expand eastwards, a serious threat that forced the Aq Qoyunlu into an alliance with the Karamanids of central Anatolia.

As early as 1464, Uzun Hasan had requested military aid from one of the Ottoman Empire's strongest enemies, Venice. Despite Venetian promises, this aid never arrived and, as a result, Uzun Hasan was defeated by the Ottomans at the Battle of Otlukbeli in 1473,[33] though this did not destroy the Aq Qoyunlu.

In 1470, Uzun selected Abu Bakr Tihrani to compile a history of the Aq Qoyunlu confederation.[34] The Kitab-i Diyarbakriyya, written in Persian, referred to Uzun Hasan as sahib-qiran and was the first historical work to assign this title to a non-Timurid ruler.[34]

Uzun Hasan preserved relationships with the members of the popular dervish order whose main inclinations were towards Shi'ism, while promoting the urban religious establishment with donations and confirmations of tax concessions or endowments, and ordering the pursuit of extremist Shiite and antinomist sects. He married his daughter Alamshah Halime Begum to his nephew Haydar, the new head of the Safavid sect in Ardabil.[35]

Sultan Ya'qub

When Uzun Hasan died early in 1478, he was succeeded by his son Khalil Mirza, but the latter was defeated by a confederation under his younger brother Ya'qub at the battle of Khoy in July.[14]: 128

Ya'qub, who reigned from 1478 to 1490, sustained the dynasty for a while longer. However, during the first four years of his reign there were seven pretenders to the throne who had to be put down.[14]: 125 Unlike his father, Ya'qub Beg was not interested in popular religious rites and alienated a large part of the people, especially the Turks. Therefore, the vast majority of Turks became involved in the Safawiya order, which became a militant organization with an extreme Shiite ideology led by Sheikh Haydar. Ya'qub initially sent Sheikh Haydar and his followers to a holy war against the Circassians, but soon decided to break the alliance because he feared the military power of Sheikh Haydar and his order. During his march to Georgia, Sheikh Haydar attacked one of Ya'qub's vassals, the Shirvanshahs, in revenge for his father, Sheikh Junayd (assassinated in 1460), and Ya'qub sent troops to the Shirvanshahs, who defeated and killed Haydar and captured his three sons. This event further strengthened the pro-Safavid feeling among Azerbaijani and Anatolian Turkmen.[3][36]

Following Ya'qub's death, civil war again erupted, the Aq Qoyunlus destroyed themselves from within, and they ceased to be a threat to their neighbors. The early Safavids, who were followers of the Safaviyya religious order, began to undermine the allegiance of the Aq Qoyunlu. The Safavids and the Aq Qoyunlu met in battle in the city of Nakhchivan in 1501 and the Safavid leader Ismail I forced the Aq Qoyunlu to withdraw.[37]

In his retreat from the Safavids, the Aq Qoyunlu leader Alwand destroyed an autonomous state of the Aq Qoyunlu in Mardin. The last Aq Qoyunlu leader, Sultan Murad, brother of Alwand, was also defeated by the same Safavid leader. Though Murād briefly established himself in Baghdad in 1501, he soon withdrew back to Diyar Bakr, signaling the end of the Aq Qoyunlu rule.

Ahmad Beg

Amidst the struggle for power between Uzun Hasan's grandsons Baysungur (son of Yaqub) and Rustam (son of Maqsud), their cousin Ahmed Bey appeared on the stage. Ahmed Bey was the son of Uzun Hasan's eldest son Ughurlu Muhammad, who, in 1475, escaped to the Ottoman Empire, where the sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror, received Uğurlu Muhammad with kindness and gave him his daughter in marriage, of whom Ahmed Bey was born.[38]

Baysungur was dethroned in 1491 and expelled from Tabriz. He made several unsuccessful attempts to return before he was killed in 1493. Desiring to reconcile both his religious establishment and the famous Sufi order, Rustam (1478–1490) immediately allowed Sheikh Haydar Safavi's sons to return to Ardabil in 1492. Two years later, Ayba Sultan ordered their re-arrest, as their rise threatened the Ak Koyunlu again, but their youngest son, Ismail, then seven years old, fled and was hidden by supporters in Lahijan.[3][39]

According to Hasan Rumlu's Ahsan al-tavarikh, in 1496–97, Hasan Ali Tarkhani went to the Ottoman Empire to tell Sultan Bayezid II that Azerbaijan and Persian Iraq were defenceless and suggested that Ahmed Bey, heir to that kingdom, should be sent there with Ottoman troops. Bayezid agreed to this idea, and by May 1497 Ahmad Bey faced Rustam near Araxes and defeated him.[38]

After Ahmad's death, the Aq Qoyunlu became even more fragmented. The state was ruled by three sultans: Alvand Mirza in the west, Uzun Hasan's nephew Qasim in an enclave in Diyarbakir, and Alvand's brother Mohammad in Fars and Iraq-Ajam (killed by violence in the summer of 1500 and replaced by Morad Mirza). The collapse of the Aq Qoyunlu state in Iran began in the autumn of 1501 with the defeat at the hands of Ismail Safavi, who had left Lahijan two years earlier and gathered a large audience of Turkmen warriors. He conquered Iraq-Ajami, Fars and Kerman in the summer of 1503, Diyarbakir in 1507–1508 and Mesopotamia in the autumn of 1508. The last Aq Qoyunlu sultan, Morad, who hoped to regain the throne with the help of Ottoman troops, was defeated and killed by Ismail's Qizilbash warriors in the last fortress of Rohada, ending the political rule of the Aq Qoyunlu dynasty.[32][3]

Governance

The leaders of Aq Qoyunlu were from the Begundur or Bayandur clan of the Oghuz Turks[40] and were considered descendants of the semi-mythical founding father of the Oghuz, Oghuz Khagan.[41] The Bayandurs behaved like statesmen rather than warlords and gained the support of the merchant and feudal classes of Transcaucasia (present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia).[41] The Aq Qoyunlu, along with the Qara Qoyunlu, were the last Iranian regimes that used their Chinggisid background to establish their legitimacy. Under Ya'qub Beg, the Chinggisid yasa (traditional nomadic laws of the medieval Turco-Mongols of the Eurasian steppe lands) was dissolved.[42]

Uzun Hasan's conquest of most of mainland Iran shifted the seat of power to the east, where the Aq Qoyunlu adopted Iranian customs for administration and culture. In the Iranian areas, Uzun Hasan preserved the previous bureaucratic structure along with its secretaries, who belonged to families that had in a number of instances served under different dynasties for several generations.[3] The four top civil posts of the Aq Qoyunlu were all occupied by Iranians, which under Uzun Hasan included; the vizier, who led the great council (divan); the mostawfi al-mamalek, high-ranking financial accountants; the mohrdar, who affixed the state seal; and the marakur "stable master", who supervised the royal court.[3]

Culture flourished under the Aq Qoyunlu, who, although of coming from a Turkic background, sponsored Iranian culture. Uzun Hasan himself adopted it and ruled in the style of an Iranian king. Despite his Turkoman background, he was proud of being an Iranian.[43] At his new capital, Tabriz, he managed a refined Persian court. There he utilized the trappings of pre-Islamic Persian royalty and bureaucrats taken from several earlier Iranian regimes. Through the use of his increasing revenue, Uzun Hasan was able to buy the approval of the ulama (clergy) and the mainly Iranian urban elite, while also taking care of the impoverished rural inhabitants.[42]

In letters from the Ottoman Sultans, when addressing the kings of Aq Qoyunlu, such titles as Arabic: ملك الملوك الأيرانية "King of Iranian Kings", Arabic: سلطان السلاطين الإيرانية "Sultan of Iranian Sultans", Persian: شاهنشاه ایران خدیو عجم Shāhanshāh-e Irān Khadiv-e Ajam "Shahanshah of Iran and Ruler of Persia", Jamshid shawkat va Fereydun rāyat va Dārā derāyat "Powerful like Jamshid, flag of Fereydun and wise like Darius" have been used.[44] Uzun Hassan also held the title Padishah-i Irān "Padishah of Iran", which was re-adopted by his distaff grandson Ismail I, founder of the Safavid Empire.[45]

The Aq Qoyunlu realm was notable for being inhabited by many prominent figures, such as the poets Ali Qushji (died 1474), Baba Fighani Shirazi (died 1519), Ahli Shirazi (died 1535), the poet, scholar and Sufi Jami (died 1492) and the philosopher and theologian, Jalal al-Din Davani (died 1503).[43]

Culture

The Aq Qoyunlu patronized Persian belles-lettres which included poets like Ahli Shirazi, Kamāl al-Dīn Banāʾī Haravī, Bābā Fighānī, Shahīdī Qumī.[46] By the reign of Yaʿqūb, the Aq Qoyunlu court held a fondness for Persian poetry.[47] 16th-century Azerbaijani poet Fuzuli was also born and raised under Aq Qoyunlu rule, writing his first known poem for Shah Alvand Mirza.[48]

Nur al-Din 'Abd al-Rahman Jami dedicated his poem, Salāmān va Absāl, which was written in Persian, to Yaʿqūb.[49][50] Yaʿqūb rewarded Jami with a generous gift.[49] Jami also wrote a eulogy, Silsilat al-zahab, which indirectly criticised Yaʿqūb immoral behavior.[46] Yaʿqūb had Persian poems dedicated to him, including Ahli Shirazi's allegorical masnavi on love, Sham' va parvana and Bana'i's 5,000 verse narrative poem, Bahram va Bihruz.[46]

Yaʿqūb's maternal nephew, 'Abd Allah Hatifi, wrote poetry for the five years he spent at the Aq Qoyunlu court.[51]

Uzun Hasan and his son, Khalil,[52] patronized, along with other prominent Sufis, members of the Kobrāvi and Neʿmatallāhi tariqats.[53] According to the Tarikh-e lam-r-ye amini by Fazlallh b. Ruzbehn Khonji Esfahni, the court-commissioned history of Yaqub's reign, Uzun Hasan built close to 400 structures in the Aq Qoyunlu region for the purpose of Sufi communal retreat.[53]

In 1469, Uzun Hasan sent the head of the Timurid Sultan, Shāhrukh II bin Abu Sa'id, with an embassy to the court of the newly ascended al-Ashraf Qaytbay in Cairo.[54] With these presents came a fathnama, in Persian, explaining to the Mamluk sultan the events leading up to the Aq Quyunlu—Timurid conflict approximately five months earlier, emphasizing in particular Sultan-Abu Sa'id's plans of aggression toward the Mamluk and Aq Quyunlu dominions—plans that were thwarted by Qaitbay's loyal peer Uzun Hasan.[55] Despite the negative response from Qaitbay,[54] Uzun Hasan's continued correspondence to the Mamluk Sultanate were in Persian.[54]

Administration

The Aq Qoyunlu administration encompassed of two sections; the military caste, which mostly consisted of Turkomans, but also had Iranian tribesmen in it. The other section was the civil staff, which consisted of officials from established Persian families.[56]

Military structure

The organization of the Aq Qoyunlu army was based on the fusion of military traditions from both nomadic and settled cultures. The ethnic background of Aq-Qoyunlu troops were quite heterogeneous as it consisted of 'sarvars' of Azerbaijan, people of Persia and Iraq, Iranzamin askers, dilavers of Kurdistan, Turkmen mekhtars and others.[57][58]

| Padishah (Sovereign) | Head of Defence Ministry Tavachi dari | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of Guards Qorchu bashi | Chief commander over army units (Amir al-Umara – Askeri qoshun) | Flag bearer (Emir alem) | Tavachi | Kadi nazir | Amir bitikchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Royal bodyguard Boy nuker | Guards (qorchu) | Engineer corps | Chief Horseman (Emir Ahur) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Garrisons | The superintendent of the hunt Amir-i Shikar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Artillery | Military inspector Ariz-i Lashkar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Road guards | Quartermaster Bukaul-i Lashkar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regular army (Jeri) | Search units Balarguchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomad units Mir-i el | Army Inspector Amiri Jandar | Jandar units | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of Food Supply Rikabdar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of Auxiliary troops Yasaul bashi | Yasaul units | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of Camping Yurtchu bashi | Yurtchu units | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Messenger Chavush | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jasus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secret agents / spies Sahib Habar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jagdiul | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of Internal Affairs Eshik Agasi Bashi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

- A flag (sanjak) belonging to Uzun Hasan (Topkapı Palace)

- Zeynel Bey Mausoleum, formerly located in Hasankeyf.

- Mehmed II and Ughurlu Muhammed (Hünername)

Coinage

- Jahangir's coin, after 1444 AD.

- Uzun Hasan's coin minted in Amid (Diyarbakir), c. 1453–1478 AD.

- Sultan Yaqub's coin, c. 1479–1490 AD.

- Baysunghur's coin minted in Tabriz, c. 1490–1493 AD.

- Sultan Rustam's coin, 1495 AD.

- Sultan Ahmad's coin minted in Tabriz, 1497 AD.

- Coin of Sultan Muhammad.

- Sultan Alwand's coin.

- Sultan Murad's coin.

See also

| History of Azerbaijan |

|---|

|

| |

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| |

| History of Iran |

|---|

The Gate of All Nations in Fars |

| Timeline |

Notes

- ^ However some Aq Qoyunlu rump states continued to rule until 1508, before they were absorbed into the Safavid Empire by Ismail I.[1]

- ^ ...Persian was primarily the language of poetry in the Aq Qoyunlu court.[5]

- ^ • Also referred to as the Aq Qoyunlu confederacy, the Aq Qoyunlu sultanate, the Aq Qoyunlu empire,[3] the White Sheep confederacy.

• Other spellings includes Ag Qoyunlu, Agh Qoyunlu or Ak Koyunlu.

• Also mentioned as Bayanduriyye (Bayandurids) in Iranian[12][11] and Ottoman sources.[13]

• Also known as Tur-'Alids in Mamluk sources.[14]: 34

References

- ^ Charles Melville (2021). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires: The Idea of Iran. Vol. 10. p. 33.

Only after five more years did Esma'il and the Qezelbash finally defeat the rump Aq Qoyunlu regimes. In Diyarbakr, the Mowsillu overthrew Zeynal b. Ahmad and then later gave their allegiance to the Safavids when the Safavids invaded in 913/1507. The following year the Safavids conquered Iraq and drove out Soltan-Morad, who fled to Anatolia and was never again able to assert his claim to Aq Qoyunlu rule. It was therefore only in 1508 that the last regions of Aq Qoyunlu power finally fell to Esma'il.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. p. 7.

Indeed, the Bayundur clan to which the Aq-qoyunlu rulers belonged, bore the same name and tamgha (symbol) as that of an Oghuz clan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "AQ QOYUNLŪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 5 August 2011. pp. 163–168.

- ^ Arjomand, Saïd Amir (2016). "Unity of the Persianate World under Turko-Mongolian Domination and Divergent Development of Imperial Autocracies in the Sixteenth Century". Journal of Persianate Studies. 9 (1): 11. doi:10.1163/18747167-12341292.

The disintegration of Timur's empire into a growing number of Timurid principalities ruled by his sons and grandsons allowed the remarkable rebound of the Ottomans and their westward conquest of Byzantium as well as the rise of rival Turko-Mongolian nomadic empires of the Aq Qoyunlu and Qara Qoyunlu in western Iran, Iraq, and eastern Anatolia. In all of these nomadic empires, however, Persian remained the official court language and the Persianate ideal of kingship prevailed.

- ^ a b Erkinov 2015, p. 62.

- ^ Lazzarini, Isabella (2015). Communication and Conflict: Italian Diplomacy in the Early Renaissance, 1350–1520. Oxford University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-19-872741-5.

- ^ Javadi & Burrill 2012.

- ^ a b Michael M. Gunter, Historical dictionary of the Kurds (2010), p. 29

- ^ a b Faruk Sümer (1988–2016). "AKKOYUNLULAR XV. yüzyılda Doğu Anadolu, Azerbaycan ve Irak'ta hüküm süren Türkmen hânedanı (1340–1514)". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (44+2 vols.) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies.

- ^ a b c d "Coins from the tribal federation of Aq Qoyunlu".

- ^ a b c Faruk Sümer (1988–2016). "UZUN HASAN (ö. 882/1478) Akkoyunlu hükümdarı (1452–1478).". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (44+2 vols.) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies.

- ^ Seyfettin Erşahin (2002). Akkoyunlular: siyasal, kültürel, ekonomik ve sosyal tarih (in Turkish). p. 317.

- ^ International Journal of Turkish Studies. Vol. 4–5. University of Wisconsin. 1987. p. 272.

- ^ a b c Woods, John E. (1999). The Aqquyunlu: Clan, Confederation, Empire. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. ISBN 0-87480-565-1.

- ^ "Aq Qoyunlu" at Encyclopædia Iranica; "Christian sedentary inhabitants were not totally excluded from the economic, political, and social activities of the Āq Qoyunlū state and that Qara ʿOṯmān had at his command at least a rudimentary bureaucratic apparatus of the Iranian-Islamic type. [...] With the conquest of Iran, not only did the Āq Qoyunlū center of power shift eastward, but Iranian influences were soon brought to bear on their method of government and their culture."

- ^ Kaushik Roy, Military Transition in Early Modern Asia, 1400–1750, (Bloomsbury, 2014), 38; "Post-Mongol Persia and Iraq were ruled by two tribal confederations: Akkoyunlu (White Sheep) (1378–1507) and Qaraoyunlu (Black Sheep). They were Persianate Turkoman Confederations of Anatolia (Asia Minor) and Azerbaijan."

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, vol. 1. Santa-Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio. p. 431. ISBN 978-159884-336-1. "His Qizilbash army overcame the massed forces of the dominant Ak Koyunlu (White Sheep) Turkomans at Sharur in 1501...".

- ^ The Book of Dede Korkut (F.Sumer, A.Uysal, W.Walker ed.). University of Texas Press. 1972. p. Introduction. ISBN 0-292-70787-8. "Better known as Turkomans... the interim Ak-Koyunlu and Karakoyunlu dynasties..."

- ^ Erdem, Ilham. "The Aq-qoyunlu State from the Death of Osman Bey to Uzun Hasan Bey (1435–1456)." (2008). “The creator of the Aq-Qoyunlu principality founded in the region of Diyarbakır was Kara Yülük Osman Bey, a member of the Bayındır tribe of the Oghuz.”

- ^ Pines, Yuri, Michal Biran, and Jörg Rüpke, eds. the limits of universal rule: Eurasian empires compared. Cambridge University Press, 2021. "the Aq Qoyunlu, like the Ottomans, began life as a collection of loosely organized band of pastoral nomadic Oghuz raiders in the Diyarbakir region of eastern Anatolia"

"the dynasty controlled territory in their eastern Anatolian homelands" - ^ Potts, Daniel T. Nomadism in Iran: from antiquity to the modern era. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- ^ Wink, André. Indo-Islamic society: 14th–15th centuries. Vol. 3. Brill, 2003.

- ^ a b Bosworth, C. E. (1 June 2019). New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-1-4744-6462-8.

- ^ Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume I. Pindar Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0907132325.

- ^ Jackson, Peter; Lockhart, Lawrence, eds. (1986). The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6, The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge University Press. p. 154.

- ^ Minorsky, Vladimir (1955). "The Aq-qoyunlu and Land Reforms (Turkmenica, 11)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 17 (3): 449. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00112376. S2CID 154166838.

- ^ Robert MacHenry. The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1993, ISBN 0-85229-571-5, p. 184.

- ^ Cornell H. Fleischer (1986). Bureaucrat and intellectual in the Ottoman Empire. p. 287.

- ^ H. B. Paksoy (1989). Alpamysh: Central Asian Identity Under Russian Rule. p. 84.

- ^ İsmail Aka (2005). Makaleler (in Turkish). Vol. 2. Berikan Kitabevi. p. 291.

- ^ Eagles 2014.

- ^ a b Tihranî, Ebu Bekr-i (2014). Kitab-ı Diyarbekriyye (PDF). Türk Tarih Kurumu. ISBN 978-9751627520.

- ^ Eagles 2014, p. 46.

- ^ a b Markiewicz 2019, p. 184.

- ^ "AKKOYUNLULAR – TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi". TDV İslam Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Woods, John E (1999). The Aqquyunlu: Clan, Confederation, Empire (PDF). University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-565-1.

- ^ Thomas & Chesworth 2015, p. 585.

- ^ a b Vladimir Minorsky. "The Aq-qoyunlu and Land Reforms (Turkmenica, 11)", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 17/3 (1955): 458.

- ^ Sarı, Arif (2019). "İran Türk Devletleri Karakoyunlular Akkoyunlular Safeviler". İnsanlığın Serüveni. İstek Yayınları.

- ^ C.E. Bosworth and R. Bulliet, The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual , Columbia University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-231-10714-5, p. 275.

- ^ a b Charles van der Leeuw. Azerbaijan: A Quest of Identity, a Short History, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-312-21903-2, p. 81

- ^ a b Lane 2016.

- ^ a b Langaroodi & Negahban 2015.

- ^ Muʾayyid S̲ābitī, ʻAlī (1967). Asnad va Namahha-yi Tarikhi (Historical documents and letters from early Islamic period towards the end of Shah Ismaʻil Safavi's reign.). Iranian culture & literature. Kitābkhānah-ʾi Ṭahūrī., pp. 193, 274, 315, 330, 332, 422 and 430. See also: Abdul Hussein Navai, Asnaad o Mokatebaat Tarikhi Iran (Historical sources and letters of Iran), Tehran, Bongaah Tarjomeh and Nashr-e-Ketab, 2536, pp. 578, 657, 701–702 and 707

- ^ H.R. Roemer, "The Safavid Period", in Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. VI, Cambridge University Press 1986, p. 339: "Further evidence of a desire to follow in the line of Turkmen rulers is Ismail's assumption of the title 'Padishah-i-Iran', previously held by Uzun Hasan."

- ^ a b c Lingwood 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Lingwood 2014, p. 111.

- ^ Mazıoğlu, Hasibe (1992). Fuzûlî ve Türkçe Divanı'ndan Seçmeler [Fuzûlî and Selections from His Turkish Divan] (in Turkish). Kültür Bakanlığı Yayımlar Dairesi Başkanlığı. p. 4. ISBN 978-975-17-1108-3.

- ^ a b Daʿadli 2019, p. 6.

- ^ Lingwood 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Lingwood 2014, p. 112.

- ^ Lingwood 2014, p. 87.

- ^ a b Lingwood 2011, p. 235.

- ^ a b c Melvin-Koushki 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Melvin-Koushki 2011, p. 193–194, 198.

- ^ V. Minorsky, "A Civil and Military Review in Fars" 881/1476, p. 172

- ^ a b Агаев, Юсиф; Ахмедов, Сабухи (2006). Ак-Коюнлу-Османская война (in Russian).

- ^ a b Erdem, I. (March 1991). "[Akkoyunlu Ordusunu Oluşturan İnsan Unsuru]". Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi (in Turkish). 15 (26): 85–92. ISSN 1015-1826.

Bibliography

- Bosworth, Clifford (1996) The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual (2nd ed.) Columbia University Press, New York, ISBN 0-231-10714-5

- Javadi, H.; Burrill, K. (May 24, 2012). "Azerbaijan x. Azeri Turkish Literature". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Among the Azeri poets of the 15th century mention should be made of Ḵaṭāʾi Tabrizi. He wrote a maṯnawi entitled Yusof wa Zoleyḵā, and dedicated it to the Aqqoyunlu Sultan Yaʿqub (r. 1478–90), who himself wrote poetry in Azeri Turkish.

- Daʿadli, Tawfiq (2019). Esoteric Images: Decoding the Late Herat School of Painting. Brill.

- Eagles, Jonathan (2014). Stephen the Great and Balkan Nationalism: Moldova and Eastern European History. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1780763538.

- Erkinov, Aftandil (2015). "From Herat to Shiraz: the Unique Manuscript (876/1471) of 'Alī Shīr Nawā'ī's Poetry from Aq Qoyunlu Circle". Cahiers d'Asie centrale. 24. Translated by Bean, Scott: 47–79.

- Lane, George (2016). "Turkoman confederations, the (Aqqoyunlu and Qaraqoyunlu)". In Dalziel, N.; MacKenzie, J.M. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe193. ISBN 978-1118455074.

- Langaroodi, Reza Rezazadeh; Negahban, Farzin (2015). "Āq-qūyūnlū". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

- Lingwood, C. G. (2011). "The qebla of Jāmi is None Other than Tabriz": ʿAbd al-Rahmān Jāmi and Naqshbandi Sufism at the Aq Qoyunlu Royal Court". Journal of Persianate Studies. 4 (2): 233–245. doi:10.1163/187471611X600404.

- Lingwood, Chad G. (2014). Politics, Poetry, and Sufism in Medieval Iran. Brill.

- Markiewicz, Christopher (2019). The Crisis of Kingship in Late Medieval Islam: Persian Emigres and the Making of Ottoman Sovereignty. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108492140.

- Melvin-Koushki, Matthew (2011). "The Delicate Art of Aggression: Uzun Hasan's "Fathnama" to Qaytbay of 1469". Iranian Studies. 44 (2 (MARCH)): 193–214. doi:10.1080/00210862.2011.541688. JSTOR 23033324.

- Morby, John (2002) Dynasties of the World: A Chronological and Genealogical Handbook (2nd ed.) Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, ISBN 0-19-860473-4

- Thomas, David; Chesworth, John A., eds. (2015). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History:Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and South America. Vol. 7. Brill. ISBN 978-9004298484.

- Woods, John E. (1999) The Aqquyunlu: Clan, Confederation, Empire (2nd ed.) University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, ISBN 0-87480-565-1

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch

![Tamga of Bayandur used by the Aq Qoyunlu[2] of Aq Qoyunlu](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3c/Tamga_of_Bayandur_%28Aq_Qoyunlu_version%29.svg/85px-Tamga_of_Bayandur_%28Aq_Qoyunlu_version%29.svg.png)