Malthusianism

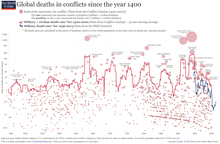

Malthusianism is a theory that population growth is potentially exponential, according to the Malthusian growth model, while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population decline. This event, called a Malthusian catastrophe (also known as a Malthusian trap, population trap, Malthusian check, Malthusian crisis, Point of Crisis, or Malthusian crunch) has been predicted to occur if population growth outpaces agricultural production, thereby causing famine or war. According to this theory, poverty and inequality will increase as the price of assets and scarce commodities goes up due to fierce competition for these dwindling resources. This increased level of poverty eventually causes depopulation by decreasing birth rates. If asset prices keep increasing, social unrest would occur, which would likely cause a major war, revolution, or a famine. Societal collapse is an extreme but possible outcome from this process. The theory posits that such a catastrophe would force the population to "correct" back to a lower, more easily sustainable level (quite rapidly, due to the potential severity and unpredictable results of the mitigating factors involved, as compared to the relatively slow time scales and well-understood processes governing unchecked growth or growth affected by preventive checks).[1][2] Malthusianism has been linked to a variety of political and social movements, but almost always refers to advocates of population control.[3]

These concepts derive from the political and economic thought of the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus, as laid out in his 1798 writings, An Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus suggested that while technological advances could increase a society's supply of resources, such as food, and thereby improve the standard of living, the abundance of resources would enable population growth, which would eventually bring the supply of resources for each person back to its original level. Some economists contend that since the Industrial Revolution in the early 19th century, mankind has broken out of the trap.[4][5] Others argue that the continuation of extreme poverty indicates that the Malthusian trap continues to operate.[6] Others further argue that due to lack of food availability coupled with excessive pollution, developing countries show more evidence of the trap as compared to developed countries.[7] A similar, more modern concept, is that of human overpopulation.

Neo-Malthusianism is the advocacy of human population planning to ensure resources and environmental integrities for current and future human populations as well as for other species.[2] In Britain the term "Malthusian" can also refer more specifically to arguments made in favour of family planning, hence organizations such as the Malthusian League.[8] Neo-Malthusians differ from Malthus's theories mainly in their support for the use of birth control. Malthus, a devout Christian, believed that "self-control" (i.e., abstinence) was preferable to artificial birth control. He also worried that the effect of contraceptive use would be too powerful in curbing growth, conflicting with the common 18th century perspective (to which Malthus himself adhered) that a steadily growing population remained a necessary factor in the continuing "progress of society", generally. Modern neo-Malthusians are generally more concerned than Malthus with environmental degradation and catastrophic famine than with poverty.

Malthusianism has attracted criticism from diverse schools of thought, including Georgists, Marxists[9] and socialists,[10] libertarians and free market advocates,[11] feminists,[12] Catholics,[13] and human rights advocates, characterising it as excessively pessimistic, insufficiently researched,[13] misanthropic or inhuman.[14][15][3][16] Many critics believe Malthusianism has been discredited since the publication of Principle of Population, often citing advances in agricultural techniques and modern reductions in human fertility.[17] Some modern proponents believe that the basic concept of population growth eventually outstripping resources is still fundamentally valid, and that positive checks are still likely to occur in humanity's future if no action is taken to intentionally curb population growth.[18][19] In spite of the variety of criticisms against it, the Malthusian argument remains a major discourse based on which national and international environmental regulations are promoted.

History

[edit]Malthus' theoretical argument

[edit]In 1798, Thomas Malthus proposed his hypothesis in An Essay on the Principle of Population.

He argued that although human populations tend to increase, the happiness of a nation requires a like increase in food production. "The happiness of a country does not depend, absolutely, upon its poverty, or its riches, upon its youth, or its age, upon its being thinly, or fully inhabited, but upon the rapidity with which it is increasing, upon the degree in which the yearly increase of food approaches to the yearly increase of an unrestricted population."[20]

However, the propensity for population increase also leads to a natural cycle of abundance and shortages:

We will suppose the means of subsistence in any country just equal to the easy support of its inhabitants. The constant effort towards population...increases the number of people before the means of subsistence are increased. The food therefore which before supported seven millions, must now be divided among seven millions and a half or eight millions. The poor consequently must live much worse, and many of them be reduced to severe distress. The number of labourers also being above the proportion of the work in the market, the price of labour must tend toward a decrease; while the price of provisions would at the same time tend to rise. The labourer therefore must work harder to earn the same as he did before. During this season of distress, the discouragements to marriage, and the difficulty of rearing a family are so great, that population is at a stand. In the mean time the cheapness of labour, the plenty of labourers, and the necessity of an increased industry amongst them, encourage cultivators to employ more labour upon their land; to turn up fresh soil, and to manure and improve more completely what is already in tillage; till ultimately the means of subsistence become in the same proportion to the population as at the period from which we set out. The situation of the labourer being then again tolerably comfortable, the restraints to population are in some degree loosened; and the same retrograde and progressive movements with respect to happiness are repeated.

— Thomas Malthus, 1798. An Essay on the Principle of Population, Chapter II.

Famine seems to be the last, the most dreadful resource of nature. The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world.

— Thomas Malthus, 1798. An Essay on the Principle of Population. Chapter VII, p. 61[21]

Malthus faced opposition from economists both during his life and since. A vocal critic several decades later was Friedrich Engels.[22][23]

Early history

[edit]Malthus was not the first to outline the problems he perceived. The original essay was part of an ongoing intellectual discussion at the end of the 18th century regarding the origins of poverty. Principle of Population was specifically written as a rebuttal to thinkers like William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet, and Malthus's own father who believed in the perfectibility of humanity. Malthus believed humanity's ability to reproduce too rapidly doomed efforts at perfection and caused various other problems.

His criticism of the working class's tendency to reproduce rapidly, and his belief that this led to their poverty, brought widespread criticism of his theory.[24]

Malthusians perceived ideas of charity to the poor, typified by Tory paternalism, were futile, as these would only result in increased numbers of the poor; these theories played into Whig economic ideas exemplified by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. The act was described by opponents as "a Malthusian bill designed to force the poor to emigrate, to work for lower wages, to live on a coarser sort of food",[25] which initiated the construction of workhouses despite riots and arson.

Malthus revised his theories in later editions of An Essay on the Principles of Population, taking a more optimistic tone, although there is some scholarly debate on the extent of his revisions.[1] According to Dan Ritschel of the Center for History Education at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County,

The great Malthusian dread was that "indiscriminate charity" would lead to exponential growth in the population in poverty, increased charges to the public purse to support this growing army of the dependent, and, eventually, the catastrophe of national bankruptcy. Though Malthusianism has since come to be identified with the issue of general over-population, the original Malthusian concern was more specifically with the fear of over-population by the dependent poor.[26]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Eugenics |

|---|

One proponent of Malthusianism was the novelist Harriet Martineau whose circle of acquaintances included Charles Darwin, and the ideas of Malthus were a significant influence on the inception of Darwin's theory of evolution.[27] Darwin was impressed by the idea that population growth would eventually lead to more organisms than could possibly survive in any given environment, leading him to theorize that organisms with a relative advantage in the struggle for survival and reproduction would be able to pass their characteristics on to further generations. Proponents of Malthusianism were in turn influenced by Darwin's ideas, both schools coming to influence the field of eugenics. Henry Fairfield Osborn Jr. advocated "humane birth selection through humane birth control" in order to avoid a Malthusian catastrophe by eliminating the "unfit".[1]

Malthusianism became a less common intellectual tradition as the 19th century advanced, mostly as a result of technological increases, the opening of new territory to agriculture, and increasing international trade.[1] Although a "conservationist" movement in the United States concerned itself with resource depletion and natural protection in the first half of the twentieth century, Desrochers and Hoffbauer write, "It is probably fair to say ... that it was not until the publication of Osborn's and Vogt's books [1948] that a Malthusian revival took hold of a significant segment of the American population".[1]

Modern formulation

[edit]

The modern formulation of the Malthusian theory was developed by Quamrul Ashraf and Oded Galor.[28] Their theoretical structure suggests that as long as higher income has a positive effect on reproductive success, and land is a limiting factor in resource production, then technological progress has only a temporary effect on income per capita (per person). While in the short run technological progress increases income per capita, resource abundance created by technological progress would enable population growth, and would eventually bring the per capita income back to its original long-run level.

The testable prediction of the theory is that during the Malthusian epoch technologically advanced economies were characterized by higher population density, but their level of income per capita was not different from the level in societies that are technologically backward.

Preventive vs. positive population controls

[edit]

To manage population growth with respect to food supply, Malthus proposed methods which he described as preventive or positive checks:

- A preventive check according to Malthus is that in which nature may alter population changes. Some primary examples are celibacy and chastity but also contraception, which Malthus condemned as morally indefensible along with infanticide, abortion and adultery.[29] In other words, preventive checks control the population by reducing fertility rates.[30]

- A positive check is any event or circumstance that shortens the human life span. The primary examples of this are war, plague and famine.[31] However, poor health and economic conditions are also considered instances of positive checks.[32] When these lead to high rates of premature death, the result is termed a Malthusian catastrophe. The adjacent diagram depicts the abstract point at which such an event would occur, in terms of existing population and food supply: when the population reaches or exceeds the capacity of the shared supply, positive checks are forced to occur, restoring balance. (In reality the situation would be significantly more nuanced due to complex regional and individual disparities around access to food, water, and other resources.)

Neo-Malthusian theory

[edit]Malthusian theory is a recurrent theme in many social science venues. John Maynard Keynes, in Economic Consequences of the Peace, opens his polemic with a Malthusian portrayal of the political economy of Europe as unstable due to Malthusian population pressure on food supplies.[33] Many models of resource depletion and scarcity are Malthusian in character: the rate of energy consumption will outstrip the ability to find and produce new energy sources, and so lead to a crisis.[7][8][9]

In France, terms such as "politique malthusienne" ("Malthusian politics") refer to population control strategies. The concept of restriction of the population associated with Malthus morphed, in later political-economic theory, into the notion of restriction of production. In the French sense, a "Malthusian economy" is one in which protectionism and the formation of cartels is not only tolerated but encouraged.[11]

Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Party and the main architect of the Soviet Union was a critic of Neo-Malthusian theory (but not of birth control and abortion in general).[34]

"Neo-Malthusianism" is a concern that overpopulation as well as overconsumption may increase resource depletion and/or environmental degradation will lead to ecological collapse or other hazards.[35]

The rapid increase in the global population of the past century exemplifies Malthus's predicted population patterns; it also appears to describe socio-demographic dynamics of complex pre-industrial societies. These findings are the basis for neo-Malthusian modern mathematical models of long-term historical dynamics.[36]

There was a general "neo-Malthusian" revival in the mid-to-late 1940s, continuing through to the 2010s after the publication of two influential books in 1948 (Fairfield Osborn's Our Plundered Planet and William Vogt's Road to Survival).[37] During that time the population of the world rose dramatically. Many in environmental movements began to sound the alarm regarding the potential dangers of population growth.[1] Paul R. Ehrlich has been one of the most prominent neo-Malthusians since the publication of The Population Bomb in 1968.[38] In 1968, ecologist Garrett Hardin published an influential essay in Science that drew heavily from Malthusian theory. His essay, "The Tragedy of the Commons", argued that "a finite world can support only a finite population" and that "freedom to breed will bring ruin to all."[39] The Club of Rome published a book entitled The Limits to Growth in 1972. The report and the organisation soon became central to the neo-Malthusian revival.[40] Leading ecological economist Herman Daly has acknowledged the influence of Malthus on his concept of a steady-state economy.[41] Other prominent Malthusians include the Paddock brothers, authors of Famine 1975! America's Decision: Who Will Survive?

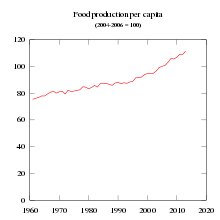

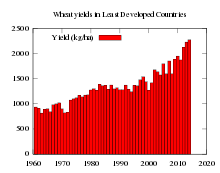

The neo-Malthusian revival has drawn criticism from writers who claim the Malthusian warnings were overstated or premature because the green revolution has brought substantial increases in food production and will be able to keep up with continued population growth.[17][42][43] Julian Simon, a cornucopian, has written that contrary to neo-Malthusian theory, Earth's "carrying capacity" is essentially limitless.[1] Simon argues not that there is an infinite physical amount of, say, copper, but for human purposes that amount should be treated as infinite because it is not bounded or limited in any economic sense, because: 1) known reserves are of uncertain quantity 2) New reserves may become available, either through discovery or via the development of new extraction techniques 3) recycling 4) more efficient utilization of existing reserves (e.g., "It takes much less copper now to pass a given message than a hundred years ago." [The Ultimate Resource 2, 1996, footnote, p. 62]) 5) development of economic equivalents, e.g., optic fibre in the case of copper for telecommunications. Responding to Simon, Al Bartlett reiterates the potential of population growth as an exponential (or as expressed by Malthus, "geometrical") curve to outstrip both natural resources and human ingenuity.[44] Bartlett writes and lectures particularly on energy supplies, and describes the "inability to understand the exponential function" as the "greatest shortcoming of the human race".

Prominent neo-Malthusians such as Paul Ehrlich maintain that ultimately, population growth on Earth is still too high, and will eventually lead to a serious crisis.[14][45] The 2007–2008 world food price crisis inspired further Malthusian arguments regarding the prospects for global food supply.[46]

From approximately 2004 to 2011, concerns about "peak oil" and other forms of resource depletion became widespread in the United States, and motivated a large if short-lived subculture of neo-Malthusian "peakists".[47]

A United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization study conducted in 2009[48] said that food production would have to increase by 70% over the next 40 years, and food production in the developing world would need to double[49] to feed a projected population increase from 7.8 billion to 9.1 billion in 2050. The effects of global warming (floods, droughts, and other extreme weather events) are expected to negatively affect food production, with different impacts in different regions.[50][51] The FAO also said the use of agricultural resources for biofuels may also put downward pressure on food availability.[52] The more recent emergence of bio-energy with carbon capture (BECCS) as a prevalent "negative emissions" strategy for reaching Paris Climate Accord goals is another such pressure.

Evidence in support

[edit]Research indicates that technological superiority and higher land productivity had significant positive effects on population density but insignificant effects on the standard of living during the time period 1–1500 AD.[53] In addition, scholars have reported on the lack of a significant trend of wages in various places over the world for very long stretches of time.[5][54] In Babylonia during the period 1800 to 1600 BC, for example, the daily wage for a common laborer was enough to buy about 15 pounds of wheat. In Classical Athens in about 328 BC, the corresponding wage could buy about 24 pounds of wheat. In England in 1800 AD the wage was about 13 pounds of wheat.[5]: 50 In spite of the technological developments across these societies, the daily wage hardly varied. In Britain between 1200 and 1800, only relatively minor fluctuations from the mean (less than a factor of two) in real wages occurred. Following depopulation by the Black Death and other epidemics, real income in Britain peaked around 1450–1500 and began declining until the British Agricultural Revolution.[55] Historian Walter Scheidel posits that waves of plague following the initial outbreak of the Black Death throughout Europe had a leveling effect that changed the ratio of land to labor, reducing the value of the former while boosting that of the latter, which lowered economic inequality by making employers and landowners less well off while improving the economic prospects and living standards of workers. He says that "the observed improvement in living standards of the laboring population was rooted in the suffering and premature death of tens of millions over the course of several generations." This leveling effect was reversed by a "demographic recovery that resulted in renewed population pressure."[56]

Robert Fogel published a study of lifespans and nutrition from about a century before Malthus to the 19th century that examined European birth and death records, military and other records of height and weight that found significant stunted height and low body weight indicative of chronic hunger and malnutrition. He also found short lifespans that he attributed to chronic malnourishment which left people susceptible to disease. Lifespans, height and weight began to steadily increase in the UK and France after 1750. Fogel's findings are consistent with estimates of available food supply.[23]

Evidence supporting Malthusianism today can be seen in the poorer countries of the world with booming populations. In East Africa[57] specifically, experts say that this area of the world has not yet escaped the Malthusian effects of population growth.[58] Jared Diamond in his book Collapse (2005), for example, argues that the Rwandan Genocide was brought about in part due to excessive population pressures. He argues that Rwanda "illustrates a case where Malthus's worst-case scenario does seem to have been right." Due to population pressures in Rwanda, Diamond explains that the population density combined with lagging technological advancements caused its food production to not be able to keep up with its population. Diamond claims that this environment is what caused the mass killings of Tutsi and even some Hutu Rwandans.[59] The genocide, in this instance, provides a potential example of a Malthusian trap.

Theory of breakout via technology

[edit]Industrial Revolution

[edit]Some researchers contend that a British breakout occurred due to technological improvements and structural change away from agricultural production, while coal, capital, and trade played a minor role.[60] Economic historian Gregory Clark, building on the insights of Galor and Moav,[61] has argued, in his book A Farewell to Alms, that a British breakout may have been caused by differences in reproduction rates among the rich and the poor (the rich were more likely to marry, tended to have more children, and, in a society where disease was rampant and childhood mortality at times approached 50%, upper-class children were more likely to survive to adulthood than poor children.) This in turn led to sustained "downward mobility": the descendants of the rich becoming more populous in British society and spreading middle-class values such as hard work and literacy.

20th century

[edit]

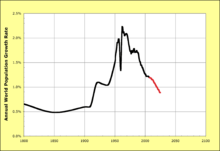

After World War II, mechanized agriculture produced a dramatic increase in productivity of agriculture and the Green Revolution greatly increased crop yields, expanding the world's food supply while lowering food prices. In response, the growth rate of the world's population accelerated rapidly, resulting in predictions by Paul R. Ehrlich, Simon Hopkins,[64] and many others of an imminent Malthusian catastrophe. However, populations of most developed countries grew slowly enough to be outpaced by gains in productivity.

By the early 21st century, many technologically developed countries had passed through the demographic transition, a complex social development encompassing a drop in total fertility rates in response to various fertility factors, including lower infant mortality, increased urbanization, and a wider availability of effective birth control.

On the assumption that the demographic transition is now spreading from the developed countries to less developed countries, the United Nations Population Fund estimates that human population may peak in the late 21st century rather than continue to grow until it has exhausted available resources.[65] Recent empirical research corroborates this assumption for most of the less developed countries, with the exception of most of Sub-Saharan Africa.[66]

A 2004 study by a group of prominent economists and ecologists, including Kenneth Arrow and Paul Ehrlich[67] suggests that the central concerns regarding sustainability have shifted from population growth to the consumption/savings ratio, due to shifts in population growth rates since the 1970s. Empirical estimates show that public policy (taxes or the establishment of more complete property rights) can promote more efficient consumption and investment that are sustainable in an ecological sense; that is, given the current (relatively low) population growth rate, the Malthusian catastrophe can be avoided by either a shift in consumer preferences[example needed] or public policy that induces a similar shift.

According to Malthus, population doubled every 25 years.[68] Population sat at less than 17 million people in the U.S. in the 1850s and a century later, according to the United States Census Bureau, population had risen to 150 million. Malthus overpopulation would lead to war, famine, and diseases and in the future, society won't be able to feed every person and eventually die. Malthus theory was incorrect, however, because by the early 1900s and mid 1900s, the rise of conventional foods brought a decline to food production and efficiency increased exponentially. More supply was being produced with less work, less resources, and less time. Processed foods had much to do with it, many wives wanting to spend less time in the kitchen and instead work. This was the beginning of technological advancements adhering to food demand even in the middle of a war. Economists disregarded Malthus population theory because Malthus didn't factor in important roles society would have on economic growth. These factors concerned the society's need to improve their quality of life and their want for economic prosperity.[68] Cultural shifts also had much to do with food production increase, and this put end to the population theory.[69][70]

Criticism

[edit]One of the earliest critics was David Ricardo. Malthus immediately and correctly recognised it to be an attack on his theory of wages. Ricardo and Malthus debated this in a lengthy personal correspondence.[71]

In Ireland, where applying his thesis, Malthus proposed that "to give full effect to the natural resources of the country a great part of the population should be swept from the soil",[72] there were early refutations. In Observations on the population and resources of Ireland (1821), Whitley Stokes, invoking the advantages mankind derives from "improved industry, improved conveyance, improvements in morals, government and religion", denied that there was a "law of nature" that procreation must outrun the means of subsistence.[73] Ireland's problem was not her "numbers" but her indifferent government.[74] In An Inquiry Concerning the Population of Nations containing a Refutation of Mr. Malthus's Essay on Population (1818), George Ensor had developed a similar broadside against Malthusian political economy,[75] arguing that poverty was sustained not by reckless propensity to propagate, but rather by the state's indulgence of the heedless concentration of private wealth.[76]

Following the same line of argument, William Hazlitt (1819) wrote, "Mr Malthus wishes to confound the necessary limits of the produce of the earth with the arbitrary and artificial distribution of that produce by the institutions of society".[77][78]

Thomas Carlyle dismissed Malthusianism as pessimistic sophistry. In Chartism (1839), he denied the possibility that "twenty-four millions" of English "working people[s]", "scattered over a hundred and eighteen thousand square miles of space", could collectively "take a resolution" to diminish the supply of labourers "and act on it". Even if they could, the ongoing influx of Irish immigrants would render their efforts redundant. Associating Malthusianism with laissez-faire, he instead advocated proactive legislation.[79] His later essay "Indian Meal" (1849) argued that maize production would remedy the failure of the potato crop as well as any prospective food shortages.[80]

Karl Marx (who had occasion to cite Ensor).[81][82] referred to Malthusianism as "nothing more than a school-boyish, superficial plagiary of Defoe, Sir James Steuart, Townsend, Franklin, Wallace".[83] Friedrich Engels argued that Malthus failed to recognise a crucial difference between humans and other species. In capitalist societies, as Engels put it, scientific and technological "progress is as unlimited and at least as rapid as that of population".[84] Marx argued, even more broadly, that the growth of both a human population in toto and the "relative surplus population" within it, occurred in direct proportion to accumulation.[83]

Henry George in Progress and Poverty (1879) criticised Malthus's view that population growth was a cause of poverty, arguing that poverty was caused by the concentration of ownership of land and natural resources. George noted that humans are distinct from other species, because unlike most species humans can use their minds to leverage the reproductive forces of nature to their advantage. He wrote, "Both the hawk and the man eat chickens; but the more hawks, the fewer chickens, while the more men, the more chickens."[85]

D. E. C. Eversley observed that Malthus appeared unaware of the extent of industrialisation, and either ignored or discredited the possibility that it could improve living conditions of the poorer classes.[86]

Barry Commoner believed in The Closing Circle (1971) that technological progress will eventually reduce the demographic growth and environmental damage created by civilisation. He also opposed coercive measures postulated by neo-malthusian movements of his time arguing that their cost will fall disproportionately on the low-income population who are struggling already.[87]

Ester Boserup suggested that expanding population leads to agricultural intensification and development of more productive and less labor-intensive methods of farming. Thus, human population levels determines agricultural methods, rather than agricultural methods determining population.[88]

Environmentalist founder of Ecomodernism, Stewart Brand, summarised how the Malthusian predictions of The Population Bomb and The Limits to Growth failed to materialise due to radical changes in fertility that peaked at a growth of 2 percent per year in 1963 globally and has since rapidly declined.[89]

Short-term trends, even on the scale of decades or centuries, cannot prove or disprove the existence of mechanisms promoting a Malthusian catastrophe over longer periods. That said, critics have pointed to the prosperity of a large part of the human population at the beginning of the 21st century, and the debatability of the predictions for ecological collapse made by Paul R. Ehrlich in the 1960s and 1970s. Economist Julian L. Simon, in The Ultimate Resource, contends that technology can prevent a Malthusian catastrophe. Medical statistician Hans Rosling also questioned its inevitability.[90]

Joseph Tainter asserts that science has diminishing marginal returns[92][incomplete short citation] and that scientific progress is becoming more difficult, harder to achieve, and more costly, which may reduce efficiency of the factors that prevented the Malthusian scenarios from happening in the past.

The view that a "breakout" from the Malthusian trap has led to an era of sustained economic growth is explored by "unified growth theory".[4][93] One branch of unified growth theory is devoted to the interaction between human evolution and economic development. In particular, Oded Galor and Omer Moav argue that the forces of natural selection during the Malthusian epoch selected beneficial traits to the growth process and this growth enhancing change in the composition of human traits brought about the escape from the Malthusian trap, the demographic transition, and the take-off to modern growth.[94]

See also

[edit]- Demographic trap

- Overshoot (population)

- Antinatalism

- Ecofascism

- John B. Calhoun and his Behavioral sink for a more detailed perspective on social pathologies that may develop prior to population collapse.

- Dysgenics as for the qualitative counterpart to Malthus' primarily quantitative concerns about human populations

- Political demography

- Cliodynamics

- Population cycle

- Population dynamics

- National Security Study Memorandum 200 - a U.S. National Security Council Study advocating population reduction in selected countries to advance U.S. interests

- Jevons paradox

- Food Race

- Resource war

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Desrochers, Pierre; Hoffbauer, Christine (2009). "The Post War Intellectual Roots of the Population Bomb" (PDF). The Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development. 1 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2010.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b Marsh, Meredith; Alagona, Peter S., eds. (2008). Barrons AP Human Geography 2008 Edition. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0-7641-3817-1.

- ^ a b Dolan, Brian (2000). Malthus, Medicine & Morality: Malthusianism after 1798. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-0851-9.

- ^ a b Galor, Oded (2005). "From Stagnation to Growth: Unified Growth Theory". Handbook of Economic Growth. Vol. 1. Elsevier. pp. 171–293.

- ^ a b c Clark, Gregory (2007). A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12135-2.

- ^ Zinkina, Julia; Korotayev, Andrey (2014). "Explosive Population Growth in Tropical Africa: Crucial Omission in Development Forecasts (Emerging Risks and Way Out)". World Futures. 70 (2): 120–139. doi:10.1080/02604027.2014.894868. S2CID 53051943.

- ^ a b Tisdell, Clem (1 January 2015). "The Malthusian Trap and Development in Pre-Industrial Societies: A View Differing from the Standard One" (PDF). University of Queensland. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ a b Hall, Lesley (2000). "Malthusian Mutations: The changing politics and moral meanings of birth control in Britain". Malthus, Medicine, & Morality. Clio Medica (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Vol. 59. Dolan (2000), Malthus, Medicine & Morality: Malthusianism after 1798, p. 141: Rodopi. pp. 141–163. doi:10.1163/9789004333338_008. ISBN 978-9042008519. PMID 11027073 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Meek, Ronald L., ed. (1973). Marx and Engels on the Population Bomb. The Ramparts Press. Archived from the original on 21 May 2000.

- ^ Commoner, Barry (May 1972). "A Bulletin Dialogue: on "The Closing Circle" – Response". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: 17–56. doi:10.1080/00963402.1972.11457931 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Simon, Julian L. (1980-06-27). "Resources, Population, Environment: An Oversupply of False Bad News". Science. 208 (4451): 1431–1437. Bibcode:1980Sci...208.1431S. doi:10.1126/science.7384784. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 7384784.

- ^ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context: South Africa, Uganda, Peru, Denmark, United States, Vietnam, Jordan. Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0-8265-1528-2., ISBN 978-0-8265-1528-5.

- ^ a b McHugh, James T. Catholic Teaching on Population Issues. Diocesan Development Program for Natural Family Planning. https://www.usccb.org/about/pro-life-activities/respect-life-program/upload/Catholic-Teaching-on-Population-Issues.pdf

- ^ a b Kunstler, James Howard (2005). The Long Emergency. Grove Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8021-4249-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Serge Luryi (May 2006). "Physics, Philosophy, and ... Ecology" (PDF). Physics Today. 59 (5): 51. doi:10.1063/1.2216962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- ^ Elwell, Frank W. (2001). "Reclaiming Malthus, Keynote address to the Annual Meeting of the Anthropologists and Sociologist of Kentucky". Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ a b Lomborg, Bjørn (2002). The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State of the World. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-521-01068-9.

- ^ Fraser, Colin (3 February 2008). "Green revolution could still blow up in our face". The Age.

- ^ Luiggi, Cristina (2010). "Still Ticking". The Scientist. 24 (12): 26. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011.

- ^ Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). "VII". An Essay on the Principle of Population.

- ^ Oxford World's Classics reprint

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (1892). The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Engels wrote that poverty and poor living conditions in 1844 had largely disappeared.

- ^ a b Fogel, Robert W. (2004). The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521808781.[page needed]

- ^ Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. p. 5. ISBN 978-1563244070 – via Google Books.

- ^ Desmond, Adrian (1992). The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. University of Chicago Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0226143743 – via Google Books.

- ^ ""Outcast London" and the late-Victorian Discovery of Poverty: Malthusianism and the New Poor Law". Archived from the original on 21 June 2007.

- ^ Wyhe, John van (2006). "Charles Darwin: gentleman naturalist: A biographical sketch".

- ^ Ashraf, Quamrul; Galor, Oded (2011). "Dynamics and Stagnation in the Malthusian Epoch". American Economic Review. 101 (5): 2003–2041. doi:10.1257/aer.101.5.2003. PMC 4262154. PMID 25506082.

- ^ Niyibizi, S. (1991). "Malthus, malthusianism, family planning and ONAPO". Imbonezamuryango (21): 5–9. PMID 12317099. French: le malthusianisme, le planning familial et l'ONAPO

- ^ "Reading: Demographic Theories | Introductory Sociology". courses.lumenlearning.com.

- ^ Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). "An Essay on The Principle of Population" (PDF). Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Simkins, Charles (2001). "Can South Africa Avoid a Malthusian Positive Check?". Daedalus. 130 (1): 123–150. JSTOR 20027682. PMID 19068951.

- ^ Garcia, Cardiff. "When Keynes pondered Malthus". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Lenin, V. I. (1913). The Working Class and Neo-Malthusianism – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Thomas Robertson (2012). The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism, Rutgers University Press.

- ^ See, e.g., Peter Turchin 2003; Turchin and Korotayev 2006 Archived February 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine; Peter Turchin et al. 2007; Korotayev et al. 2006.

- ^ Thomas Robertson (2012). The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism, Rutgers University Press, p 36-60.

- ^ Thomas Robertson (2012). The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism, Rutgers University Press, p 126-151.

- ^ Hardin, Garrett (1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science. 162 (3859): 1243–1248. Bibcode:1968Sci...162.1243H. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. PMID 17756331.

- ^ Dieren, Wouter van, ed. (1995). Taking Nature Into Account: A Report to the Club of Rome. Springer Books. ISBN 978-0387945330.

- ^ Daly, Herman E. (1991). Steady-state economics (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Island Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-1559630726.

- ^ Gardner, Dan (2010). Future Babble: Why Expert Predictions Fail – and Why We Believe Them Anyway. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- ^ Martinez-Alier, Joan; Masjuan, Eduard. "Neo-Malthusianism in the Early 20th Century" (PDF). Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.

- ^ Bartlett, Al (September 1996). "The New Flat Earth Society". The Physics Teacher. 34 (6): 342–343. doi:10.1119/1.2344473. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; Ehrlich, Anne H. (2009). "The Population Bomb Revisited" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development. 1 (3): 63–71. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ Brown, Lester (May–June 2011). "The New Geopolitics of Food". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew (2015). Peak oil: apocalyptic environmentalism and libertarian political culture. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226285573. OCLC 951562545.[page needed]

- ^ "2050 High-Level Experts Forum: Issues briefs". www.fao.org.

- ^ "FAO - News Article: 2050: A third more mouths to feed". Food and Agriculture Organization.

- ^ "Special Report on Climate Change and Land — IPCC site".

- ^ Flavelle, Christopher (August 8, 2019). "Climate Change Threatens the World's Food Supply, United Nations Warns". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "FAO says Food Production must Rise by 70%". Population Institute. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Ashraf, Quamrul; Galor, Oded (2011). "Dynamics and Stagnation in the Malthusian Epoch". American Economic Review. 101 (5): 2003–2041. doi:10.1257/aer.101.5.2003. PMC 4262154. PMID 25506082.

- ^ Allen, R. C. (2001). "The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War". Explorations in Economic History. 38 (4): 411–447. doi:10.1006/exeh.2001.0775.

- ^ Overton, Mark (1996). Agricultural Revolution in England: The transformation of the agrarian economy 1500–1850. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521568593.

- ^ Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. pp. 292–293, 304. ISBN 978-0691165028.

- ^ Ban, Zoltan (2016-11-16). "Malthusian Catastrophe Unfolding Across ME-Africa Region, With Egypt As A Case Study | Seeking Alpha". seekingalpha.com. Retrieved 2023-02-11.

- ^ Korotayev, Andrey; Zinkina, Julia (2015). "East Africa in the Malthusian Trap? A statistical analysis of financial, economic, and demographic indicators". arXiv:1503.08441 [q-fin.GN].

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse. New York: Viking Press. pp. 311–328. ISBN 978-0670033379.

- ^ Tepper, Alexander; Borowiecki, Karol J. (2013). Accounting for Breakout in Britain: The Industrial Revolution through a Malthusian Lens (Report). Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 639.

- ^ Voth, Hans-Joachim (2008). "Clark's intellectual Sudoku". European Review of Economic History. 12 (2): 149–155. doi:10.1017/S1361491608002190.

- ^ "Historical Estimates of World Population". Archived from the original on 2 March 2000.

- ^ "faostat3". Food and Agriculture Organization, see graph metadata for further details.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Hopkins, Simon (1966). A Systematic Foray into the Future. Barker Books. pp. 513–569.[ISBN missing]

- ^ "2004 UN Population Projections" (PDF). United Nations.

- ^ Crombach, L.; Smits, J. (2021). "The Demographic Window of Opportunity and Economic Growth at Sub-National Level in 91 Developing Countries". Social Indicators Research.

- ^ Arrow, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Goulder, L.; Daily, G.; Ehrlich, P.; Heal, G.; Levin, S.; Mäler, K.; Schneider, S.; Starrett, D.; Walker, B. (2004). "Are We Consuming Too Much". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (3): 147–172. doi:10.1257/0895330042162377.

- ^ a b Sandmo, Agnar (2011). "4". Economics Evolving: A History of Economic Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ “New Ways to Make Food Are Coming-but Will Consumers Bite?” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, www.economist.com/leaders/2021/10/02/new-ways-to-make-food-are-coming-but-will-consumers-bite.

- ^ "Major Moments in Food & Agriculture: 1900's Until Now". 13 May 2020.

- ^ Ricardo, David (2005). Sraffa, Piero (ed.). The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo. M. H. Dobb. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund11 vols

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Mokyr, Joel (1980). "Malthusian Models and Irish History". The Journal of Economic History. 40 (1): (159–166), 159. doi:10.1017/S0022050700104681. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2120439. S2CID 153849339.

- ^ Stokes, Whitley (1821). Observations on the Population and Resources of Ireland. Joshua Porter. pp. 4, 8, 13–14.

- ^ Stokes (1821), pp. 89-91

- ^ Rothschild, Emma (1995). "Echoes of the Malthusian Debate at the Population Summit". Population and Development Review. 21 (2): (351–359), 355. doi:10.2307/2137498. ISSN 0098-7921. JSTOR 2137498.

- ^ Ensor, George (1818). An Inquiry Concerning the Population of Nations: Containing a Refutation of Mr. Malthus's Essay on Population. London: E. Wilson.

- ^ Hazlitt, William (1819). Political Essays. London: William Hone. p. 426.

- ^ Rothschild (1995), p. 351

- ^ Jordan, Alexander (19 May 2017). "Thomas Carlyle and Political Economy: The 'Dismal Science' in Context". The English Historical Review. 132 (555): 286–317. doi:10.1093/ehr/cex068. ISSN 0013-8266.

- ^ Cumming, Mark, ed. (2004). "Indian Meal". The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0838637920.

- ^ Karl Marx (1869), "Marx to Engels" (6. November), Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Ireland and the Irish Question, New York, International Publishers, 1972, p. 388.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1889). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production. Appleton & Company. pp. 753 n.5.

- ^ a b Karl Marx (transl. Ben Fowkes), Capital Volume 1, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1976 (originally 1867), pp. 782–802.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich. "Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy", Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, 1844, p. 1.

- ^ "Progress and Poverty, Chapter 8". www.henrygeorge.org. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Eversley, David Edward Charles (1959). Social theories of fertility and the Malthusian debate. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0837176284. OCLC 1287575.[page needed]

- ^ Thomas Robertson (2012). The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism, Rutgers University Press, p 181-184.

- ^ Boserup, Ester (1966). "The Conditions of Agricultural Growth. The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure". Population. 21 (2): 402. doi:10.2307/1528968. JSTOR 1528968.

- ^ Brand, Stewart (2010). Whole Earth Discipline. Atlantic. ISBN 978-1843548164.[page needed]

- ^ Simon, Julian L, "More People, Greater Wealth, More Resources, Healthier Environment", Economic Affairs: J. Inst. Econ. Affairs, April 1994.

- ^ Fischer, R. A.; Byerlee, Eric; Edmeades, E. O. "Can Technology Deliver on the Yield Challenge to 2050" (PDF). Expert Meeting on How to Feed the World. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: 12.

- ^ Tainter, Joseph. The Collapse of Complex Societies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2003. [ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Galor, Oded (2011). Unified Growth Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Galor, Oded; Moav, Omer (2002). "Natural Selection and The Origin of Economic Growth". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 117 (4): 1133–1191. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.199.2634. doi:10.1162/003355302320935007.

Further reading

[edit]- Revelle, Roger (6 January 1974). "How We Can Exorcise the Ghost of Malthus". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- Korotayev, A.; Malkov, A.; Khaltourina, D. (2006). Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow: URSS. ISBN 5-484-00414-4.

- Korotayev, A.; Malkov, A.; Khaltourina, D. (2006). Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends. Moscow: URSS. ISBN 5-484-00559-0. See especially Chapter 2 of this book

- Korotayev, A.; Khaltourina, D. (2006). Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends in Africa. Moscow: URSS. ISBN 5-484-00560-4.

- Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). "An Essay on the Principle of Population" (PDF). Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project (First ed.). London. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Turchin, P., et al., eds. (2007). History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies. Moscow: KomKniga. ISBN 5-484-01002-0

- Turchin, P.; Korotayev, A. (2006). "Population Dynamics and Internal Warfare: A Reconsideration". Social Evolution & History. 5 (2): 112–47.

- A Trap At The Escape From The Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2/2 (2011): 1–28.

- Lueger, T. (2019). The Principle of Population and the Malthusian Trap. Darmstadt Discussion Papers in Economics 232, 2018. The Principle of Population and the Malthusian Trap

- Malthus, Thomas Robert (1826). An Essay on the Principle of Population: A View of its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness; with an Inquiry into Our Prospects Respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils which It Occasions (Sixth ed.). London: John Murray.

- Pomeranz, Kenneth (2000). The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09010-8.

- Rosen, William (2010). The Most Powerful Idea in the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6705-3.

- Wells, Roger (1988). Wretched Faces: Famine in Wartime England 1793-1801. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-0-862-99333-7.

- A Trap At The Escape From The Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2/2 (2011): 1–28.

External links

[edit]- "The Opposite of Malthus". Jason Godesky. The Anthropik Network. Archived from the original on 2015-07-11.

- Essay on life of Thomas Malthus

- Malthus' Essay on the Principle of Population

- David Friedman's essay arguing against Malthus' conclusions

- United Nations Population Division World Population Trends homepage

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch