Redistricting in Wisconsin

| Elections in Wisconsin |

|---|

|

Redistricting in Wisconsin is the process by which boundaries are redrawn for municipal wards, Wisconsin State Assembly districts, Wisconsin State Senate districts, and Wisconsin's congressional districts. Redistricting typically occurs—as in other U.S. states—once every decade, usually in the year after the decennial United States census. According to the Wisconsin Constitution, redistricting in Wisconsin follows the regular legislative process, it must be passed by both houses of the Wisconsin Legislature and signed by the Governor of Wisconsin—unless the Legislature has sufficient votes to override a gubernatorial veto. Due to political gridlock, however, it has become common for Wisconsin redistricting to be conducted by courts. The 1982, 1992, and 2002 legislative maps were each enacted by panels of United States federal judges; the 1964 and 2022 maps were enacted by the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

The most recent legislative redistricting occurred in February 2024, when governor Tony Evers signed 2023 Wisconsin Act 94. This followed a 2023 decision by the Wisconsin Supreme Court to strike down the previous legislative maps, ending 12 years of extreme partisan gerrymandering in Wisconsin.

The congressional maps were last set in April 2022, when the Wisconsin Supreme Court selected a map in the Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission lawsuit, with only minor changes from the map passed by the legislature 10 years earlier.

Background

[edit]Reapportionment of representatives between the states every ten years based on new census figures is required by Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution and Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.[1] The Constitution, Supreme Court jurisprudence, and federal law allow significant latitude to the individual states to draw their congressional and legislative districts as they see fit, as long as each district contains roughly equivalent numbers of people (see Baker v. Carr, Wesberry v. Sanders, and Reynolds v. Sims) and provides for minority representation pursuant to the Voting Rights Act.

Article IV of the Constitution of Wisconsin mandates that redistricting must occur in the first legislative session following the publication of a new enumeration by the United States census.[2] The Assembly must have between 54 and 100 districts, and the Senate must have no more than one-third and no less than one-quarter of the members of the Assembly.[3] The Wisconsin Constitution further specifies that the boundary of a Senate district cannot cross the boundary of an Assembly district,[4] that the boundary of an Assembly district cannot cross a ward boundary, and that districts should be "in as compact form as practicable".[5]

Wisconsin Constitution, Article IV, Section 2. The number of the members of the assembly shall never be less than fifty−four nor more than one hundred. The senate shall consist of a number not more than one−third nor less than one−fourth of the number of the members of the assembly.

Wisconsin Constitution, Article IV, Section 3. At its first session after each enumeration made by the authority of the United States, the legislature shall apportion and district anew the members of the senate and assembly, according to the number of inhabitants.

Wisconsin Constitution, Article IV, Section 4. The members of the assembly shall be chosen biennially, by single districts, on the Tuesday succeeding the first Monday of November in even−numbered years, by the qualified electors of the several districts, such districts to be bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines, to consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable.

Wisconsin Constitution, Article IV, Section 5. The senators shall be elected by single districts of convenient contiguous territory, at the same time and in the same manner as members of the assembly are required to be chosen; and no assembly district shall be divided in the formation of a senate district. The senate districts shall be numbered in the regular series, and the senators shall be chosen alternately from the odd and even−numbered districts for the term of 4 years.

Since the Wisconsin Constitution requires single-member districts and mandates that a State Senate district cannot divide a State Assembly district, and since U.S. Supreme Court and Wisconsin Supreme Court opinions require roughly equal representation for each state legislative district, all State Senate districts in Wisconsin are composed of a collection of exactly three State Assembly districts. This system was first formally established in a highly contentious 1972 redistricting plan (1971 Wisc. Act 304). Prior to 1972, counties were allocated a specific number of Assembly districts based on populations, and Senate districts might contain between 1 and 6 Assembly districts.[6]

In the December 2023 Wisconsin Supreme Court case Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, the court ruled that the language of the state constitution requires districts to meet strict contiguity requirements. Prior to that decision, it had become common in Wisconsin since the federal court redistricting in 1992 to follow a looser contiguity standard, which had allowed for municipalities which had non-contiguous precincts to be considered "politically contiguous" for the purpose of redistricting. The court found that the federal standard did not meet the requirements of the Wisconsin constitution, and ruled that all territory belonging to a legislative district must be actually connected.

Process

[edit]The redistricting process begins with each decennial census, when the U.S. government provides detailed census tract data to the states, usually by March 1 of the first year of the decade. In Wisconsin, the state then provides the data to the counties, and each of Wisconsin's 72 counties—in collaboration with the counties' municipal governments—draws new county board and municipal ward boundaries. Counties are required to submit draft boundaries within 60 days of receiving the census data, and no later than July 1 of the first year of the decade. Over the 60 days beginning that July 1, counties and municipalities are directed to come to agreement on their final ward plan and update the county district plan to reflect the agreed wards. Collaboration is necessary because, while the county government ultimately controls the county board districts, the municipal ward boundaries are defined by the municipal governments, and the county board must adhere to the ward lines drawn by the municipalities in the formation of county districts. Wisconsin law does not require wards to be equal in population, but does specify a range depending on the size of the municipality:

- For municipalities with a population of 150,000 or greater, wards must contain between 1,000 and 4,000 people.

- For municipalities with a population between 39,000 and 149,999, wards must contain between 800 and 3,200 people.

- For municipalities with a population between 10,000 and 38,999, wards must contain between 600 and 2,100 people.

- For municipalities with fewer than 10,000 people, wards must be between 300 and 1,000 people.

- Municipalities with fewer than 1,000 people are not required to divide into wards.

If any municipality fails to submit a ward plan by the statutory deadline, any voter living in the municipality can submit a plan to the Wisconsin circuit court which has jurisdiction over that municipality, and the court can either adopt that plan or amend the plan as they see fit. The municipality can still supersede a plan imposed under such circumstances by passing their own ward plan. Ward lines are required to remain stable for the decade and cannot be changed after a plan is adopted.

After the wards have been drawn, counties are directed to hold public hearings on the county district plan. Cities are given another 60 days to draw new aldermanic districts based on the new ward lines. Aldermanic districts, unlike ward boundaries, can be changed with a 2/3 vote of the municipal council. Towns and villages, under Wisconsin law, elect their boards at-large and do not draw aldermanic districts.

The Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau compiles the county and ward data, with detailed population statistics, into a database which is usually ready by September 1. From there, typically the two major parties will each devise one or more preferred legislative maps for their parties interests, usually prioritizing their partisan advantage, but also considering interests such as (a) protecting incumbents, (b) maintaining influence in particular geographic areas, (c) tending to the concerns of a particular interest group or population or industry, etc. From there, the legislative process plays out between the legislature and the governor, with influence and lobbying from external parties with their own interests in the outcome.

Since 1983, the Wisconsin Legislature and Governor have only been able to successfully pass a redistricting law once—in 2011, when Republicans held full control of state government. In 1992 and 2002, with the Legislature and Governor unable to reach an agreement, the state maps were drawn by panels of United States federal judges. Divided government in 2021 and 2022 again resulted in a court-ordered plan.

Reform attempts

[edit]For over a century in Wisconsin, there have been movements to implement a nonpartisan redistricting commission to draw state legislative districts, rather than leaving it in the hands of a partisan legislature or an arbitrary judicial panel. This was briefly adopted with the redistricting commissions of the mid-20th century, the most famous being the Rosenberry Commission of the 1950s. The current Governor, Tony Evers, again attempted to empower a nonpartisan commission in 2020. He created a new redistricting commission by executive order, with its members chosen by a panel of Wisconsin state judges.[7][8] A number of Wisconsin cities and counties also passed "advisory referendums" indicating their support for a nonpartisan redistricting commission.[9][10] But the commission's work was ultimately ignored by the legislature and played little role in the result of the 2020 redistricting.

Under pressure from the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 2023, Republicans in the Legislature proposed a change to redistricting law to put the redistricting process more in the hands of the independent Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau. They likened this proposal to the "Iowa model" for redistricting. This attempt was rejected by the governor, as critics said it left too much power in the hands of the Legislature to ultimately overrule the independent Bureau.[11]

History

[edit]

The original Wisconsin Constitution of 1848 specified the exact boundaries of the 19 original State Senate districts and 66 original Assembly districts in Article XIV, Section 12, and the 2 original congressional districts in Article XIV, Section 10.[12] The first congressional redistricting occurred during the 1st Wisconsin Legislature (1848), after the United States Congress allocated a third congressional district to Wisconsin (1848 Wisc. Act 11).

Congressional reapportionment after the 1860 United States census added three more congressional districts to the state of Wisconsin. The 14th Wisconsin Legislature drew the new congressional districts (1861 Wisc. Act 238). The 1870 United States census resulted in the addition of two additional congressional districts. Wisconsin added 1 more seat in the 1880, 1890, and 1900 reapportionments. The 11th congressional district was eliminated following the 1930 United States census.[13] The 10th congressional district was eliminated following the 1970 United States census. The 9th congressional district was eliminated following the 2000 United States census.[14]

The first state legislative redistricting occurred in the 5th Wisconsin Legislature (1852 Wisc. Act 499) in which the Legislature added six Senate districts and sixteen Assembly districts. As new counties were organized under the state government, additional redistricting was necessitated and new districts were added rapidly in the first 12 years. In the 9th Wisconsin Legislature (1856 Wisc. Act 109) the number of senators was increased from 25 to 30 and the number of representatives was increased from 82 to 97. The number was increased again in 1861 (1861 Wisc. Act 216), when the number of senators increased to 33 and the number of representatives increased to the constitutional maximum, 100.

Although the United States Supreme Court would, in the 21st century, specify that state legislative districts had to represent a roughly equal number of inhabitants, that requirement did not exist in the early years of Wisconsin's history, and the early State Legislature districts had wide variations in population representation. That changed in Wisconsin when the Wisconsin Supreme Court asserted a requirement for more uniformity in legislative district population in the 1892 court cases which collectively established what was referred to as the "Cunningham Principles" for redistricting.

The U.S. Supreme Court's strict interpretation of "one person-one vote" resulted in the decision to reduce the Assembly from 100 seats to 99 in 1972 and adopt the model of three Assembly districts per Senate district.[15] This new process also opened the door to more elaborate districts, no longer constrained by county boundaries. Whether due to the changed rules or due to changing politics, since 1972 a court-ordered plan has been necessitated in four of the next five redistricting cycles.

Cunningham cases (1892)

[edit]The first major court case resulting from redistricting in Wisconsin occurred in 1892. The 1890 election had given Democrats full control of state government for the first time in decades. The Legislature passed a plan that was signed by Governor George Wilbur Peck. Republicans balked at the electoral implications, as well as the large number of split-county districts in the new map. Republicans sued the Secretary of State, Democrat Thomas Cunningham, in the Wisconsin Supreme Court to prevent the utilization of the new districts for the 1892 election. Democratic attorney and politician Edward S. Bragg, who was hoping to be chosen as United States Senator by the next Democratic Legislature, worked as counsel for the Secretary of State in defending the redistricting plan. Republican Charles E. Estabrook, the former Attorney General, worked as counsel for the Republican plaintiffs.

In the case State ex rel. Attorney General v. Cunningam the State Supreme Court struck down the map. Justice Harlow S. Orton wrote for the majority that: (1) the maps did not properly account for the population of non-taxed Native Americans and members of the Army and Navy who were not currently located in the state; (2) the districts did not closely adhere to county lines; and that districts were not properly (3) contiguous, (4) compact, and (5) convenient. The court also found that the districts varied too widely in population, with the most populous Senate district being nearly twice the population of the smallest.[16]

The Legislature went back to work and, in a special 1892 session, passed another redistricting map (1892 Wisc. S.S. 1 Act 1). Although this map adhered more closely to county lines, it still varied widely in district population, and was again challenged by Republicans in the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The Court again, in September 1892, ruled in favor of the Republicans and struck down the map in State ex rel. Lamb v. Cunningham.[17] The Legislature passed a third and final plan in October 1892, in a second special session (1892 Wisc. S.S. 2 Act 1). The final plan was signed October 27, just 12 days before the 1892 general election, when almost all of the nominations had already been submitted. Due to the extreme lateness of the maps, further legislation was needed to clarify the status of the existing nominations and the necessary process for getting nominees on the ballot for the new districts.

Later referred to as the "Cunningham Principles" the 1892 court cases established the role of the State Supreme Court in adjudicating legislative maps, and set the precedent that districts should adhere to county lines and strive for uniformity in district population.

Consequences for 1890s elections

[edit]Although Democrats made large gains in the State Senate in the 1892 election, they lost seats in the Assembly. In the 1894 election, Republicans regained the majority in both chambers. The maps, therefore, did not appear to have a significant partisan implication. This also occurred in an era when Wisconsin still had two opportunities for legislative redistricting per decade, and a second redistricting was passed in a February 1896 extraordinary session of the Legislature, which reverted many of the districts to their pre-1892 boundaries (1896 Wisc. S. S. Act 1).[18]

Rosenberry Commission (1950s)

[edit]

By 1950, it had been nearly 30 years since the Wisconsin Legislature had passed a full redistricting plan. The 1931 law (1931 Wisc. S.S. Act 27) made only minor changes to the 1921 plan, and no redistricting act was passed subsequent to the 1940 census. The Legislature's inaction led to a lawsuit on constitutional grounds, but the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in State ex rel Martin v. Zimmerman that they could not compel the Legislature to pass a redistricting plan.[19] With the population changes since 1920, the districts had fallen far from the goal of equal representation and the issue had begun to cause political agitation in the state. In 1950, responding to public pressure, the Legislative Council created an apportionment study committee, composed of two senators, three representatives, and three members of the public. The committee was chaired by recently retired Chief Justice Marvin B. Rosenberry and came to be known as the "Rosenberry Commission".[20]

Within four months, the commission produced a plan for redistricting which would restore equal representation in district populations, but it struggled to win majority support in the Republican-dominated Legislature.[21][22] The measure was fiercely opposed by rural legislators and farm interests, who demanded an alternative scheme to allow the Senate to be redistricted based on land area and population, as opposed to basing it solely on attempting to achieve equal population representation in districts. A compromise was eventually reached, in which the Legislature passed the Rosenberry plan (1951 Wisc. Act 728) with a provision which delayed implementation until voters could register their opinion on the question of using land area as criteria for drawing districts.[23] The question was put to voters in the 1952 fall general election, and voters defeated the requirement for land-based representation.[24]: 780

Nevertheless, Wisconsin Republicans and Republican-aligned interest groups did not give up on the idea, and, in the 1953 Legislature, proposed a new constitutional amendment to require land-based criteria for the drawing of Senate districts. This time the referendum appeared on the Spring 1953 ballot; with roughly half the turnout of the Fall election, the amendment was narrowly approved.[24]: 779 Republicans in the Legislature took this as permission to rewrite the Rosenberry plan and draw Senate districts which fit the new constitutional requirement.

The Legislature passed 1953 Wisc. Act 242, which they deemed as superseding Rosenberry, and 1953 Wisc. Act 550 which amended a number of Assembly districts. The new districts were quickly challenged in a number of state court cases. In State ex rel. Thomson v. Zimmerman the Wisconsin Supreme Court nullified the 1953 referendum, ruling that the ballot language did not properly describe the constitutional change being proposed. They further ruled that it was unconstitutional for the Legislature to enact more than one redistricting per decennial census unless Section 3 of Article IV of the Wisconsin Constitution were amended to allow it.[25] Following the Supreme Court ruling, the Rosenberry plan was utilized for the remainder of the 1950s.

Consequences for 1950s elections

[edit]Immediately after the Rosenberry maps took effect, in the 1954 election, Republicans lost their super-majority in the Assembly, dropping to their smallest majority since 1942. In 1958, the Democrats won control of the Assembly for the first time since 1932.

Reynolds cases (1960s)

[edit]

In the 1960s, with the state then under divided government, redistricting proved even more difficult. They again attempted to utilize a Legislative Council Committee of legislators and citizens as they had in 1950. In 1961, however, the Council Committee map was referred to the full Legislature without the endorsement of the Committee. The Republican Legislature did not pass the Committee map and failed to pass any other map that year. As in the 1950 reapportionment saga, Republicans continued attempting to utilize geographic area as criteria in the drawing of districts, which the Democratic governor, Gaylord Nelson, rejected.[26]

Governor Nelson called a special session in 1962 to deal with the issue, but then vetoed the congressional and legislative maps produced by the special session.[26] Attempts were made to override his veto, but all failed. The Senate then attempted to pass a redistricting plan via joint resolution, which would bypass the Governor, but the Assembly did not agree that it would be constitutional. In the meantime, the Democratic Attorney General, John W. Reynolds Jr., had gone to federal court seeking a resolution. The U.S. District Court appointed former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice Emmert L. Wingert as special master to investigate the issue. Judge Wingert eventually reported that he believed the redistricting suit should be dismissed and found no evidence that the failure to redistrict would result in "discrimination". The court accepted his recommendation and dismissed the suit, though they did warn that the issue could be renewed if no redistricting plan was passed by August 1963.[27]

The 1962 elections produced the same divided government configuration, with a Republican Legislature and a new Democratic governor—John Reynolds, the former Attorney General. In May of 1963, the governor and legislature were finally able to come to a compromise on the congressional district map, but legislative redistricting remained stalled.[28] Once again, the Legislature passed a Republican-approved map, and the Democratic Governor vetoed it. Finally, in July 1963, the Assembly and Senate concurred on passing a joint resolution to bypass the Governor. Reynolds, however, brought suit to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which ruled in State ex rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman that the Wisconsin Constitution did not permit the Legislature to bypass the Governor in redistricting and further stated that if no new plan was enacted by May 1, the court would produce its own map by May 15.[29]

A last-ditch effort was made by the Legislature, but their final attempt was again rejected by Governor Reynolds, who criticized the partisan bias of the map, calling it "a fraud upon the people".[30]

On May 14, 1964, the Wisconsin Supreme Court issued its own plan in a filing in State ex rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman (23 Wis. 2d 606). The new plan was embraced by Governor Reynolds, who called it, "the culmination of my four-year fight for equal voting rights for the people of the state of Wisconsin."[31]

Consequences for 1960s elections

[edit]In the first election under the court-ordered map (1964), Democrats gained the majority in the Assembly, but Republicans quickly regained the majority in 1966 and there was little change in the composition of the Senate.

Equal representation requirement (1972)

[edit]

The 1970s redistricting cycle was the first to occur in Wisconsin after the federal government had formalized the "one-person, one-vote" mandate, written into the intent of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and verified by the United States Supreme Court. This presented technical challenges for redistricting in Wisconsin, due to several provisions of the State Constitution:

- First and foremost, the State Constitution set out the clear requirement that no Senate district could divide an Assembly district, thus every Senate district must be composed of one or more whole Assembly districts. With the Senate at 33 members and the Assembly at 100, they obviously could not create an equal distribution of 100 seats into 33.

- The State Constitution also set 100 as the maximum number of Assembly districts, and set the maximum number of Senate seats at one third of the Assembly, so it was impossible to achieve an equal ratio of Assembly to Senate seats without eliminating a seat.

- The State Constitution also strictly required that members of both chambers be chosen in single-member districts, so the option of reaching equal representation through use of larger multi-member districts was also not possible.

- The State Constitution further stated that Assembly districts adhere to county, precinct, town or ward lines, which, for 124 years, was interpreted to strictly respect county boundaries. This was also one of the issues litigated in the 1892 Cunningham cases, with the Wisconsin Supreme Court stating that county lines should be adhered to.

Once again, Wisconsin was under divided government, with the Senate in Republican control and the Assembly and Governorship held by Democrats. Despite the state losing a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, the congressional redistricting was accomplished with bipartisan support before the end of 1971 (1971 Wisconsin Act 133).[32] Legislative redistricting took a back seat for the year, as many in the Senate and Assembly were resigned to leaving the process to the courts.[33]

Democratic state representative Fred Kessler led the effort to produce a map which took radical new steps to meet the "one-person, one-vote" requirement.[34] The Kessler plan reduced the Assembly size from 100 seats to 99, and established the three Assembly districts per Senate district ratio to make it possible to achieve roughly equal-population districts in the Assembly and Senate. The plan further called for abandoning the adherence to county boundaries, which had previously served as the basis for Assembly district assignments.[34] On the county question, Kessler stated, "I'd say it's completely and totally impossible to follow county lines and meet the court's requirements."[34] The Assembly Elections Committee backed Kessler's plan,[35] and the Senate concurred on the need to go to 99 districts and abandon county lines, but the two chambers remained divided on the final map.[36] Kessler suggested his plan was drafted to maximize party competition and alleged the Senate plan attempted to maximize Republican partisan advantage.[36]

In early 1972, at the urging of Senate Republican leader Ernest Keppler, Governor Patrick Lucey appointed a commission to evaluate the redistricting plans to try to come to a consensus.[37][38] The commission's work stalled, however, as the chairman, former State Supreme Court justice James Ward Rector, was opposed to the crucial change in consideration of county boundaries, and the commission found it was impossible to write a map with equal representation while honoring county lines.[39] Republican commission member Stanley York noted that they could perhaps achieve both goals by simultaneously amending the district lines and the county lines.[39] The commission broke in February, unable to come to consensus.[40]

The matter went back to the Legislature, which attempted to resolve the issue in a conference committee. But again, the committee deadlocked, and the Legislature appeared prepared to let the issue go to the courts for resolution.[41] The Wisconsin Supreme Court, prompted by Attorney General Robert W. Warren, declared that the existing 1964 boundaries were now unconstitutional due to population changes and needed to be redrawn. They gave the Legislature until April 17 to pass a plan, and vowed that the court would again enact its own plan if the Legislature failed.[42]

Governor Lucey called a special session of the Legislature to deal with redistricting in April, as Republicans sought action from the State Supreme Court and Democrats sought a plan from the U.S. District Court in Milwaukee.[43] The Supreme Court agreed to extend its deadline to April 24 to allow the Legislature to work. The Legislature eventually came to a compromise plan which prioritized preservation of incumbents while adopting the Kessler changes to enable the plan to achieve equal-representation.[44] The result was declared a gerrymander, but constitutional.[45] The redistricting plan was ultimately passed late in the evening of April 21, 1972 (1971 Wisc. Act 304).[46]

Consequences from 1972 plan

[edit]Under the 1972 map, Democrats won a majority in the State Senate for the first time since 1892 and maintained their majority in the Assembly. In the congressional redistricting, one Republican district was eliminated and in 1976 the Democrats reached a 7–2 majority in the congressional delegation. Though these partisan results were likely also driven by the national mood, which had turned decisively against Republicans due to the Watergate scandal.

The 1972 plan was also noteworthy for abandoning the adherence to county boundaries in the redistricting process, which led to more elaborate districts and gerrymanders in subsequent years.

Federal court intervention (1982)

[edit]

In the 1980s redistricting cycle, in an inversion of the 1960s and 1970s, the Democrats were in control of the State Legislature with a Republican Governor, Lee S. Dreyfus. A stalemate ensued once again, with the Democratic Legislature passing their preferred plan and Governor Dreyfus issuing a veto.[47][48] With the impasse stretching into 1982, a lawsuit was filed in federal court seeking a resolution. On February 5, 1982, U.S. District Judge Terence T. Evans indicated that if a plan was not signed into law by April, the court would order their own plan.[49] Later that month, the federal court declared that the current legislative districts had become unconstitutional due to population changes in the 1980 census.[50] In the spring of 1982, the Legislature and Governor were able to agree on a new congressional map, but remained at an impasse over legislative redistricting.[51] Governor Dreyfus sought to have the case removed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, but the case was ultimately retained by a three-judge panel of the federal Eastern District of Wisconsin.[50]

With no plan in place in May 1982, the court made another threat—that they could slash the size of the State Legislature as punishment for the government's inability to come to a compromise.[52] A last-ditch effort by the Legislature was again vetoed by the Governor. In June 1982, the court ordered its own plan and admonished the state government for failing to come to an agreement.[50] Legislators and journalists noted at the time that the map was clearly drawn in a way to punish incumbents, and drew 53 of the 138 state legislators into incumbent-vs-incumbent races.[53][54]

The court order did not settle reapportionment for the decade, however, as the Democratic Legislature remained unhappy with the new maps.[54] They received further incentive in the 1982 election, where Democrat Tony Earl was elected to succeed Republican Lee Dreyfus as governor. In the spring of 1983, Governor Earl called a special session of the Legislature to draw up a new redistricting plan.[55] Within a month, the Democratic plan was passed into law and signed, and a new court battle ensued.[56][57] In the spring of 1984, the federal court struck down the Democratic plan, ordering the state to revert to the 1982 court-ordered plan.[58] State Democrats, however, appealed the ruling to the United States Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court stayed the District Court order in June,[59] and, after hearing arguments, maintained the stay and allowed the 1983 redistricting plan to supersede the 1982 court-ordered plan.[60]

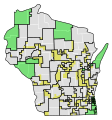

- Changes in boundaries for the State Assembly following 1983 Act 29Territory which was moved into a new districtDistricts which were entirely unchanged

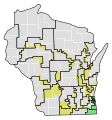

- Changes in boundaries for the State Senate following 1983 Act 29Territory which was moved into a new districtDistricts which were entirely unchanged

Consequences from the 1980s redistrictings

[edit]Politically, Democrats gained 2 seats in the Senate, but there was no change in the Assembly partisan makeup. Historically, the court-ordered Assembly district numbers appear as a strange aberration in historical data. The 1983 act which superseded the court-order saw more of a shift back towards Republicans, though Democrats remained in the majority in both houses of the Legislature through to the next redistricting cycle.

Walker/Fitzgerald gerrymander (2011)

[edit]In the 2010 elections, Republicans won significant majorities in both houses of the Legislature and the governorship. Republicans used their majorities to pass a radical redistricting plan after the 2010 census which substantially shifted the partisan bias of the state legislative maps and the state congressional map (2011 Wisc. Act 43). The redistricting process also broke with state procedure by publishing their prescribed legislative district map before the counties and municipalities had completed the process of drawing wards. The Legislature further ordered that municipalities and counties were directed to draw ward lines to comply with the legislative district boundaries set by the state government—legally inverting the bottom-up redistricting process into a top-down process. The map itself was the product of a Republican project known as REDMAP, created to maximize the partisan bias of redistricting by utilizing new statistical and mapping software.[61]

Several lawsuits were brought against the 2011 redistricting plan. A set of early challenges against the plan—alleging various Equal Protection Clause violations—were consolidated in the case Baldus v. Members of the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board. The ruling in that case dismissed most of the plaintiffs claims, citing that, while the districts clearly were drawn to partisan benefit, the population distribution was roughly equal. The court made only minor alterations to two districts in the Milwaukee area, which the court ruled violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by improperly diluting the population of Latinos across two districts.[62]

Following this defeat, another lawsuit was brought on equal protection grounds which offered a novel methodology for measuring the partisan impact of gerrymandering. The inability to quantify the severity of a partisan gerrymander had previously been cited by the U.S. Supreme Court as a factor limiting federal courts from providing a remedy. In the case of Whitford v. Gill, a panel of federal judges agreed that the 2011 redistricting act represented an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, and adopted their own three-part test to determine the validity of a district map: (1) was the map intended to place a severe impediment on the effectiveness of the votes of individual citizens on the basis of their political affiliation, (2) does the map actually have that effect, and (3) can the map be justified on any other, legitimate legislative grounds.[63][64] The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and was one of a number of redistricting challenges that went before the high court in the latter part of the decade. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the plaintiffs in Whitford lacked standing, remanding the case to the lower court, where it was later dismissed. The more significant gerrymandering case of that term, however, was Benisek v. Lamone, dealing with a Maryland gerrymander, where the Supreme Court stated that redistricting was an inherently political question that the court could not adjudicate.[65]

Consequences from 2011 plan

[edit]The 2011 Wisconsin redistricting has been one of the most successful partisan gerrymanders in the history of the country, entrenching Republican majorities in both houses of the Wisconsin Legislature with near supermajorities. The bias of the 2011 map was best illustrated in the 2018 Fall election, when Democrats won every statewide race, and won 53% of the statewide legislative vote, yet only won 36 of the state's 99 Assembly seats.[66][67]

Wisconsin Supreme Court re-asserting jurisdiction (2021–2024)

[edit]During the 105th Wisconsin Legislature (2021–2022), Wisconsin was again under divided government. Again both sides proposed their own maps, knowing there was little or no hope for a compromise. The biggest difference about the 2020 decade was the activity of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which re-asserted a role as arbitrator of redistricting for the first time in 60 years. The conservative 4–3 majority on the Court chose to take original jurisdiction over the redistricting case at the urging of state Republican leadership. This was a major break with Wisconsin Supreme Court precedent, as the court had refused on a near-unanimous basis to take on redistricting cases since 1964, and had deferred several times to the federal courts. The 2002 redistricting case of Jensen v. Wisconsin Elections Board best illustrates this precedent, where a unanimous Wisconsin Supreme Court described that the state court lacked the proper constitutional, statutory, or legal framework to justify taking the case, and further explained that the legal procedure of the federal court was more conducive to adjudicate and dispose of such cases.[68][69][70]

The 2020 redistricting cycle was further complicated by delays and controversies involving the 2020 United States census, which was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and significant litigation. The United States Census Bureau announced in March 2021 that they would not meet their deadlines, and ultimately did not release detailed census-tract data until August 12, 2021—about five months behind schedule.[71][72] In response to the census delays, Republicans in the 105th Wisconsin Legislature sought to delay the county and municipal redistricting process, which would not have had any effect on the legislative redistricting cycle in advance of the 2022 elections.[73]

For his part, Democratic governor Tony Evers established a nonpartisan, non-political commission for redistricting, known as the People's Maps Commission, hoping to win bipartisan support for a consensus plan.[74][75] But those maps were rejected by the Republican state legislature. Several Democrats also voted against the proposal, due to perceived dilution of ethnic minority votes.[76]

The Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in November 2021, in a 4–3 decision on ideological lines, that the standard they would use to draw new maps would be to seek the "least changes" to the existing maps necessary to comply with the new census data.[77] Because the state court lacked relevant statutes or precedent, this "least changes" requirement was a novel standard without a basis in Wisconsin law or legal history.[78] The standard alone conferred significant partisan advantage to the Republican Party in this map-making process, since the existing map had been intentionally designed in 2011 to give partisan advantage to Republican candidates.

Several parties submitted their preferred legislative maps to the Court, adhering to the "least changes" guidance. Governor Evers's proposal was shown to move the fewest number of voters into new districts from the 2011 plan, and therefore best adhered to the Court's guidance. Nevertheless, the Court still broke on nearly ideological lines, with the one swing vote joining the liberals in a 4–3 decision adopting Evers's maps.[79][80]

This settlement was immediately challenged to the Supreme Court of the United States, which threw out the Wisconsin Supreme Court decision in an unsigned opinion on March 23, 2022.[81] The U.S. Supreme Court justified their decision on criticism of the flawed process the Wisconsin Supreme Court had adopted in their strained attempt to hear the redistricting case—specifically, they stated that the state court had not given proper consideration to the federal law question of racial gerrymandering with the new legislative maps, which would have created a new majority-black Assembly district.[81]

A few weeks later, the Wisconsin Supreme Court returned and simply selected the Republican proposal which had been submitted prior to their March decision, even though this map suffered from the same process defect as the Democratic map.[82]

Consequences of 2022 plan

[edit]Under the Republican plan adopted by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, legislative Republicans immediately expanded their already-significant majorities, achieving a long-desired supermajority in the Wisconsin Senate—the first supermajority in a Wisconsin legislative chamber since 1983. Democrats, however, were able to prevent Republicans from achieving a supermajority in the Assembly, thus preserving Governor Evers's veto power during the 106th Wisconsin Legislature.[83]

2023 Supreme Court election and new redistricting effort

[edit]After the Republican maps were utilized for the 2022 Wisconsin elections, the following April, the 2023 Wisconsin Supreme Court election flipped the majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The Democratic-aligned legal advocacy group Law Forward promised a new round of lawsuits to try to strike down the legislative maps before the 2024 elections.[84][85] The lawsuit was filed by Democratic voters a day after the start of the new Supreme Court term, on August 2, 2023.[86]

The Republican speaker of the Assembly, Robin Vos, responded with a threat to impeach the newest justice, Janet Protasiewicz, accusing her of prejudging the redistricting issue less than a month after she took office. After backlash from state and national Democrats, and after the idea was dismissed by conservative former justices, Vos backed down from his impeachment threats.[87][88][89][90]

On October 7, the Wisconsin Supreme Court agreed to take up the case on redistricting, though they declined to adjudicate the complaint that the maps created a partisan advantage; they chose to only focus the case on the narrow technical issue of contiguity.[91]

The Wisconsin Supreme Court released their decision in the case, Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, on December 22, 2023, declaring the legislative maps unconstitutional in a 4–3 opinion along ideological lines. Justice Jill Karofsky wrote for the majority, declaring that state legislative districts must be composed of "physically adjoining territory" and pointing out that 50 of 99 existing Assembly districts failed that constitutional criteria.[92] The majority decision also declared that the "least changes" methodology devised by the court in 2022 for the Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission case was never properly defined by the court, was found to be unworkable in that case's remedy, and was without legal or constitutional foundation anyway. In a dissenting opinion, justice Brian Hagedorn pointed out that the Wisconsin Supreme Court still lacked any proper procedure for handling redistricting cases.[93]

The court set a schedule for a remedial plan, accepting remedial map submissions from each of the parties in the litigation. In February 2024, as the court seemed poised to select one of the four Democratic remedial map proposals in the Clarke case, Republicans in the state legislature chose to embrace Governor Evers' map proposal. They first passed an amended version of the map to try to protect a handful of incumbents. After that map was vetoed, they passed Evers' map without changes, which he signed into law on February 19, 2024.[94][95][96][97]

While the remedial process was playing out for the legislative maps, in January 2023 Elias Law Group brought a lawsuit asking the Wisconsin Supreme Court to also strike down Wisconsin's congressional district map. They argued that the Clarke decision—which struck down the "least changes" rationale used to create the 2022 maps—meant that the congressional maps were no longer based on any legal foundation.[98] The Wisconsin Supreme Court refused this case, opting to leave the 2022 congressional map intact.[99]

Wisconsin redistricting laws and court orders

[edit]- Article XIV, Wisconsin Constitution, 1848

- 1848 Wisc. Act 11, grew from 2 to 3 congressional districts.

- 1852 Wisc. Act 499, expanded to 25 senators and 82 representatives.

- 1856 Wisc. Act 109, expanded to 30 senators and 97 representatives.

- 1861 Wisc. Act 216, expanded to 33 senators and 100 representatives.

- 1861 Wisc. Act 238, grew from 3 to 6 congressional districts.

- 1866 Wisc. Act 101

- 1871 Wisc. Act 156

- 1871 Wisc. Act 157, made an amendment to 1871 Wisc. Act 156.

- 1872 Wisc. Act 48, grew from 6 to 8 congressional districts.

- 1872 Wisc. Act 70, reconfigured the Monroe Assembly districts.

- 1876 Wisc. Act 343

- 1882 Wisc. Act 242

- 1882 Wisc. Act 244, grew from 8 to 9 congressional districts.

- 1887 Wisc. Act 461

- 1891 Wisc. Act 482, struck down by court, never utilized.

- 1891 Wisc. Act 483, grew from 9 to 10 congressional districts.

- 1892 Wisc. S.S. 1 Act 1, struck down by court, never utilized.

- 1892 Wisc. S.S. 2 Act 1

- 1896 Wisc. S.S. Act 1

- 1901 Wisc. Act 194, for 1901 Assembly redistricting.

- 1901 Wisc. Act 309, for 1901 Senate redistricting.

- 1901 Wisc. Act 398, grew from 10 to 11 congressional districts.

- 1911 Wisc. Act 661

- 1921 Wisc. Act 470

- 1931 Wisc. S. S. Act 27, made only minor changes

- 1931 Wisc. S. S. Act 28, reduced from 11 congressional districts to 10.

- 1951 Wisc. Act 728, Rosenberry Plan, went into effect in 1954 elections.

- 1953 Wisc. Act 242, attempt to replace Rosenberry Plan, struck down by court, never utilized.

- 1963 Wisc. Act 63, congressional redistricting

- State ex rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman, 23 Wis. 2d 606 (1964), legislative redistricting ordered by the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

- 1971 Wisc. Act 133, reduced from 10 congressional districts to 9.

- 1971 Wisc. Act 304, reduced the Assembly to 99 seats, set 3:1 relationship of Assembly to Senate seats.

- 1981 Wisc. Act 154, congressional redistricting.

- 1981 Wisc. Act 155, amended 1981 Wisc. Act 154.

- Wisconsin State AFL-CIO v. Elections Board, 543 F. Supp. 630 (1982), legislative redistricting ordered by United States District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin.[53][100][101]

- 1983 Wisc. Act 29, superseded the court-ordered 1982 map, initially struck down by the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, but the decision was later stayed by the Supreme Court of the United States, and the map was utilized for the remainder of the 1980s.[102][103]

- 1991 Wisc. Act 256, congressional redistricting.

- Prosser v. Elections Board, 793 F. Supp. 859 (1992), legislative redistricting ordered by United States District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin.

- Jensen v. Wisconsin Elections Board (2002), Wisconsin Supreme Court declined jurisdiction and pointed out that they lack proper procedure for handling redistricting.

- Baumgart v. Wendelberger (2002), legislative redistricting ordered by United States District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

- Baumgart v. Wendelberger (2002), corrections to the previous 2002 decision.

- 2011 Wisc. Act 43, legislative redistricting

- 2011 Wisc. Act 44, congressional redistricting

- Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (March 2022), original 2022 redistricting decision by Wisconsin Supreme Court—legislative and congressional maps.

- Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (April 2022), revised 2022 redistricting decision after the SCOTUS opinion—legislative maps only.

- Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (Dec. 2023), ruled the legislative maps from Johnson were unconstitutional.

- 2023 Wisc. Act 94, replaced the legislative maps from Johnson (April 2022)

See also

[edit]- Elections in Wisconsin

- Political party strength in Wisconsin

- 2020 United States census

- 2020 United States redistricting cycle

References

[edit]- ^ "The Constitution of the United States". National Archives and Records Administration. November 4, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Article IV, Section 3, Wisconsin Constitution". Wisconsin Legislature. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Article IV, Section 2, Wisconsin Constitution". Wisconsin Legislature. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Article IV, Section 5, Wisconsin Constitution". Wisconsin Legislature. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Article IV, Section 4, Wisconsin Constitution". Wisconsin Legislature. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau (1973). "Legislature" (PDF). In Theobald, H. Rupert; Robbins, Patricia V. (eds.). The state of Wisconsin 1973 Blue Book (Report). Madison, Wisconsin: State of Wisconsin. pp. 227–230. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Relating to Creating the People's Maps Commission (PDF) (Executive Order 66). Governor of Wisconsin. January 27, 2020.

- ^ Schmidt, Mitchell (September 11, 2020). "Gov. Tony Evers announces members of nonpartisan maps commission". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Mosher Salazar, Angelina (October 22, 2020). "Redistricting Advisory Referendum On The Ballot In 11 Wisconsin Counties". WUWM. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Behnke, Duke (January 21, 2021). "Appleton sets April 6 referendum to measure voter support for nonpartisan redistricting". The Post-Crescent. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Reid, Claire (September 13, 2023). "Robin Vos proposed 'Iowa-style' redistricting for Wisconsin. What does that mean?". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Constitution of the State of Wisconsin" (PDF). Manual for the use of the Assembly of the State of Wisconsin for the year 1853 (Report). Madison, Wisconsin: State of Wisconsin. 1853. pp. 36–42. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Black, Ruby A. (December 22, 1930). "Wisconsin Men in Congress Fear Reapportionment". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved February 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schneider, Pat (December 28, 2000). "State will lose seat in House". The Capital Times. p. 1A. Retrieved February 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Boundary Battle Just Beginning". Wisconsin State Journal. November 24, 1970. p. 10. Retrieved February 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ State ex rel. Attorney General v. Cunningam, 81 Wis. 440 (Wisconsin Supreme Court March 22, 1892).

- ^ State ex rel. Lamb v. Cunningham, 83 Wis. 90 (Wisconsin Supreme Court September 27, 1892).

- ^ Casson, Henry, ed. (1897). "Miscellaneous" (PDF). The Blue Book of the state of Wisconsin (Report). State of Wisconsin. pp. 642–648. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ State ex rel Martin v. Zimmerman, 249 Wis. 101 (Wisconsin Supreme Court June 22, 1946).

- ^ "State Civil Defense Committee Named". Wisconsin State Journal. August 22, 1950. p. 3. Retrieved February 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Republicans Get Ready To Scuttle Reapportionment Again". The Capital Times. December 27, 1950. p. 18. Retrieved February 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Another Stall on Reapportionment". The Capital Times. February 27, 1951. p. 22. Retrieved February 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ignoring Party Pledges, GOP Refuses to Follow Mandate to Reapportion". The Capital Times. June 21, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved February 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Toepel, M. G.; Kuehn, Hazel L., eds. (1954). "Parties and Elections: Constitutional Amendments and Referendum" (PDF). The Wisconsin Blue Book, 1954 (Report). State of Wisconsin. pp. 779–780. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ State ex rel. Thomson v. Zimmerman, 264 Wis. 644 (Wisconsin Supreme Court October 6, 1953).

- ^ a b Robbins, William C. (July 20, 1962). "Two Districting Foes Air Sides Before Wingert". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 3. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wisconsin v. Zimmerman, 209 F. Supp. 183 (W.D. Wis. August 14, 1962).

- ^ "Legislature Redistrict Deadlock Looming Now". Wisconsin State Journal. May 21, 1963. p. 5. Retrieved June 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ State ex rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman, 22 Wis. 2d 544 (Wisconsin Supreme Court February 28, 1964).

- ^ Revell, Aldric (May 4, 1964). "Reynolds on Top". The Capital Times. p. 28. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brissee, William (May 15, 1964). "High Court Remap Gives 25 Seats to Milwaukee County". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 2. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Reapportionment Bill Becomes Law". Wisconsin State Journal. November 16, 1971. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wyngaard, John (June 14, 1971). "Reapportionment: Lawmakers Tacitly Agree to Disagree". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 11. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Thompson, Kessler Propose New Reapportionment Plan". Wisconsin State Journal. September 23, 1971. p. 6. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Legislative Redistrict Plan is Backed, 5-2". Wisconsin State Journal. October 12, 1971. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Waixel, Vivian (January 14, 1972). "Few Appear for Reapportionment Hearing". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Selk, James D. (January 16, 1972). "Reapportion Tops Agenda". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lucey Agrees to Remap Panel". Wisconsin State Journal. January 6, 1972. p. 3. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Rector Will Oppose Remap Which Skips County Lines". Wisconsin State Journal. January 25, 1972. p. 19. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Reapportionment Unit Breaks Up in Discord". Wisconsin State Journal. February 15, 1972. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Remapping Issue Still Hangs in Air". Wisconsin State Journal. March 10, 1972. p. 2. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Simms, Patricia (March 14, 1972). "Redistricting is Legislative Job, Court Declares". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 26. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Selk, James D. (April 6, 1972). "Legislature is Recalled to Reapportion State". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 12. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Selk, James D. (April 21, 1972). "Remapping Bill Stalls in Assembly". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Legislature Passes Remap, Women's Rights". Wisconsin State Journal. April 23, 1972. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Selk, James D. (April 22, 1972). "Redistricting Passes, but Usury Bill Waits". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved January 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreyfus Vetoes Congressional Remap". Wisconsin State Journal. November 28, 1981. p. 1. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Remap Plan Vetoed". Wisconsin State Journal. November 28, 1981. p. 2. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "State Given Remap Deadline". Wisconsin State Journal. February 6, 1982. p. 3. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Wisconsin State AFL-CIO v. Elections Board, 543 F. Supp. 630 (E.D. Wis. June 9, 1982).

- ^ Hunter, John Patrick (March 19, 1982). "Dreyfus Set to Sign Remapping Bill". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 22. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter, John Patrick (May 18, 1982). "Legislature Size Could be Slashed in Remap Move". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Fanlund, Paul (June 20, 1982). "Incumbents lose in border wars". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Rix, Paul A. (June 12, 1982). "Riled-up Senate seeks remap accord". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fanlund, Paul (July 10, 1983). "Lawmakers Tackle Remapping Again". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 4. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ An Act ... relating to redistricting the Senate and Assembly based on the 1980 federal census ... (Act 29). Wisconsin Legislature. 1983. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Rix, Paul A. (July 28, 1983). "GOP Takes Dem Remap Plan to Federal Court". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 6. Retrieved August 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Republican Party of Wisconsin v. Elections Board, 585 F. Supp. 603 (E.D. Wis. May 25, 1984).

- ^ Wisconsin Elections Board v. Republican Party of Wisconsin, 467 U.S. 1232 (Supreme Court of the United States June 7, 1984).

- ^ Wisconsin Elections Board v. Republican Party, 468 U.S. 1201 (Supreme Court of the United States July 2, 1984).

- ^ Zelizer, Julian E. (June 17, 2016). "The power that gerrymandering has brought to Republicans". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Baldus v. Members of the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, 849 F. Supp. 2d 840 (E.D. Wis. March 22, 2012).

- ^ Whitford v. Gill, 218 F. Supp. 3d 837 (W.D. Wis. November 21, 2016).

- ^ Treleven, Ed (November 22, 2016). "Federal judges panel finds state redistricting plan an 'unconstitutional gerrymander'". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Vetterkind, Riley (June 28, 2019). "U.S. Supreme Court decision leaves Wisconsin gerrymandering case with few prospects". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Gilbert, Craig. "New election data highlights the ongoing impact of 2011 GOP redistricting in Wisconsin". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Brogan, Dylan (November 15, 2018). "No contest". Isthmus. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Jensen v. Wisconsin Elections Board, 249 Wis. 2d 706 (Wisconsin Supreme Court February 12, 2002).

- ^ Marley, Patrick (January 14, 2021). "Wisconsin Supreme Court casts doubts on Republican-backed redistricting rules". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Shawn (May 14, 2021). "Wisconsin Supreme Court Rejects Proposal To Change Redistricting Rules". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Lieb, David A. (March 28, 2021). "Census data delay scrambles plans for state redistricting". Associated Press. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Opoien, Jessie (August 12, 2021). "New census data kicks off Wisconsin's next redistricting battle". The Capital Times. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Bauer, Scott (June 2, 2021). "Local elections new front in Wisconsin redistricting battle". Associated Press. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Conniff, Ruth (October 1, 2021). "People's Maps Commission releases voting maps". Wisconsin Examiner. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ "People's Maps Commission Submits Final Fair Maps to Gov. Evers and Legislature". The People's Maps Commission. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ "Democrats slam district maps drawn by People's Map's Commission, GOP map heads to Evers' desk". CBS58. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Shawn (November 30, 2021). "In win for Republicans, Wisconsin Supreme Court promises 'least changes' approach to redistricting". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ "Fair Elections Project: Statement on WI Supreme Court decision and 2021 redistricting". Fair Elections Project (Press release). March 3, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2023 – via Wispolitics.com.

- ^ Johnson, Shawn (January 18, 2022). "Wisconsin Supreme Court to hear arguments in redistricting case". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Marley, Patrick (March 3, 2022). "Wisconsin Supreme Court picks Democratic Gov. Tony Evers' maps in redistricting fight". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Liptak, Adam (March 23, 2022). "Supreme Court Sides With Republicans in Case on Wisconsin Redistricting". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Shawn (April 15, 2022). "Wisconsin Supreme Court chooses maps drawn by Republicans in new redistricting decision". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "Democratic victories block Republican supermajority in the Wisconsin Assembly". PBS Wisconsin. November 9, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ Epstein, Reid J. (April 4, 2023). "Liberal Wins Wisconsin Court Race, in Victory for Abortion Rights Backers". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ Kelly, Jack (April 6, 2023). "Liberal law firm to argue gerrymandering violates Wisconsin Constitution". The Capital Times. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Beck, Molly (August 2, 2023). "Lawsuit challenging Wisconsin's legislative maps to be filed at the state Supreme Court today". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Beck, Molly; Opoien, Jessie (September 12, 2023). "Vos backs turning turning over drawing of election maps to nonpartisan agency in bid to bypass lawsuits". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "2023 Assembly Bill 415". Wisconsin Legislature. September 12, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Shur, Alexander; Schmidt, Mitchell (September 12, 2023). "Tony Evers rejects Republican proposal to adopt nonpartisan redistricting process". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Schmidt, Mitchell (October 11, 2023). "Jon Wilcox, third former justice exploring impeachment, also opposes the idea". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ Waldron, Megan O’Matz, Lucas (November 17, 2023). "Wisconsin's Legislative Maps Are Bizarre, but Are They Illegal?". ProPublica. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bosman, Julie (December 22, 2023). "Justices in Wisconsin Order New Legislative Maps". The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ "Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (2023AP1399-OA)" (PDF). Wisconsin Supreme Court. December 22, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ Kremer, Rich (February 19, 2024). "Evers signs new maps into law, effectively ending Wisconsin redistricting lawsuit". WPR. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Wise, David (February 19, 2024). "Gov. Evers: Signs fair maps for Wisconsin". WisPolitics. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Journal, Alexander Shur | Wisconsin State (February 16, 2024). "Democrats see Republican ruse to protect speaker in map bill; records show no partisan intent". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Journal, Alexander Shur | Wisconsin State Journal, Mitchell Schmidt | Wisconsin State (February 19, 2024). "Gov. Tony Evers signs his legislative maps into law, giving Democrats big boost in Legislature". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Andrea, Lawrence (January 16, 2024). "Democratic law firm challenges Wisconsin's congressional district lines in filing with state Supreme Court". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Kremer, Rich (March 1, 2024). "Supreme Court won't hear lawsuit seeking to redraw Wisconsin's congressional maps". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ Rix, Paul A. (June 20, 1982). "Recapping the redistricting battle". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Judges who redrew the boundaries". Wisconsin State Journal. June 20, 1982. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Associated Press (July 17, 1983). "GOP may challenge remap plan". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Associated Press (July 3, 1984). "Order could end remap struggle". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 5. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch